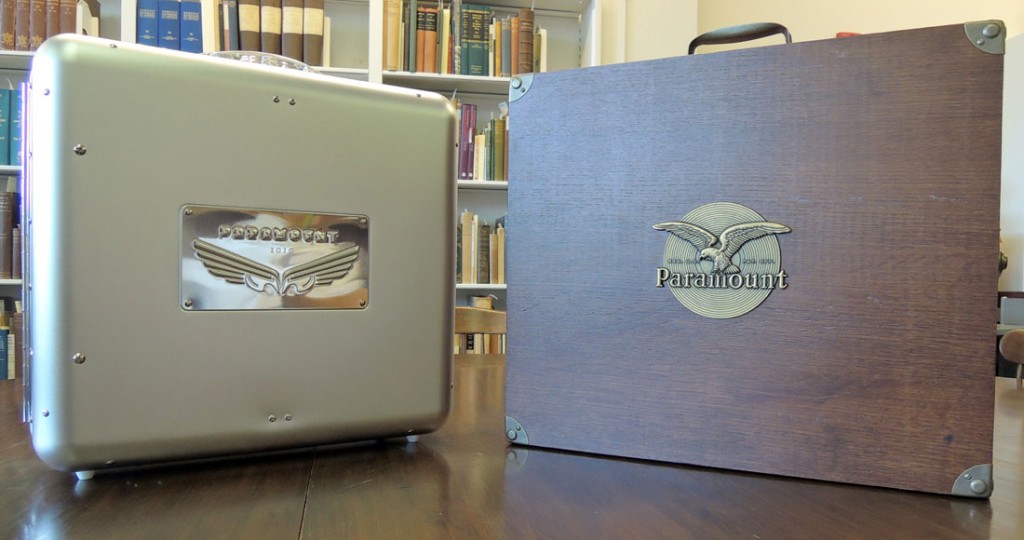

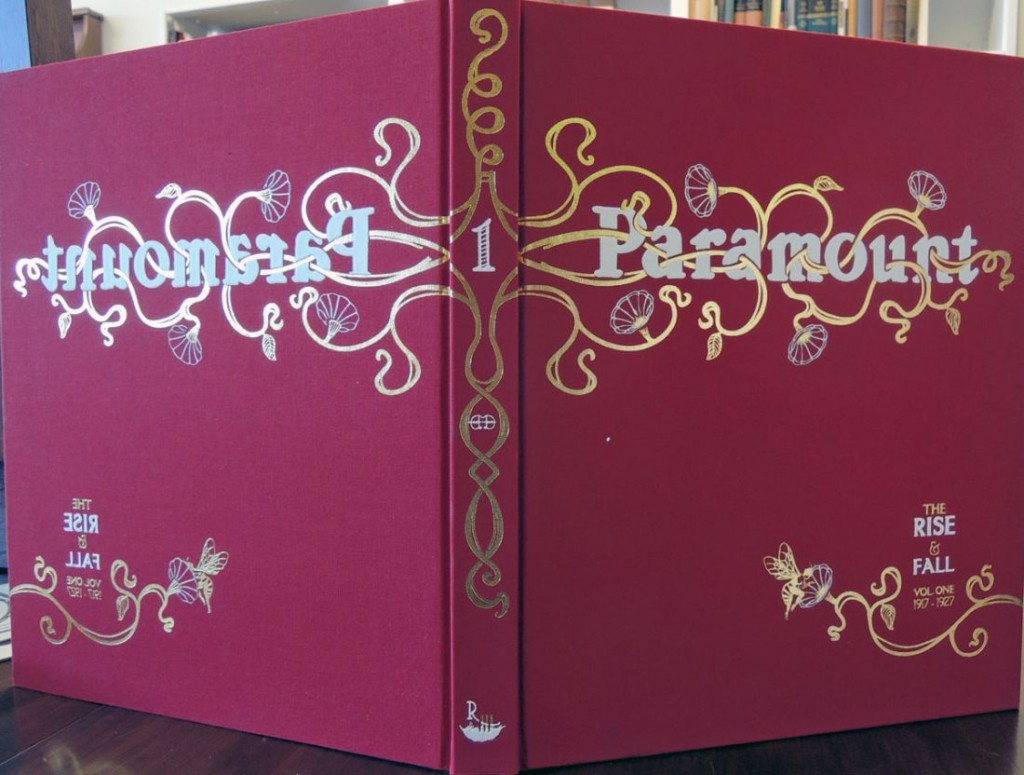

It is hard to know where multi-media editions should be kept in a university setting. After consultation with colleagues, the Graphic Arts Collection has acquired The Rise and Fall of Paramount Records vol. 1 and 2. Released jointly from John Fahey’s Revenant and Jack White’s Third Man Records, the material was co-produced by the leading scholar on Paramount, Alex van der Tuuk. Volume one (below left) covers 1917 to 1927 and volume two (below right) chronicles 1928 to 1932.

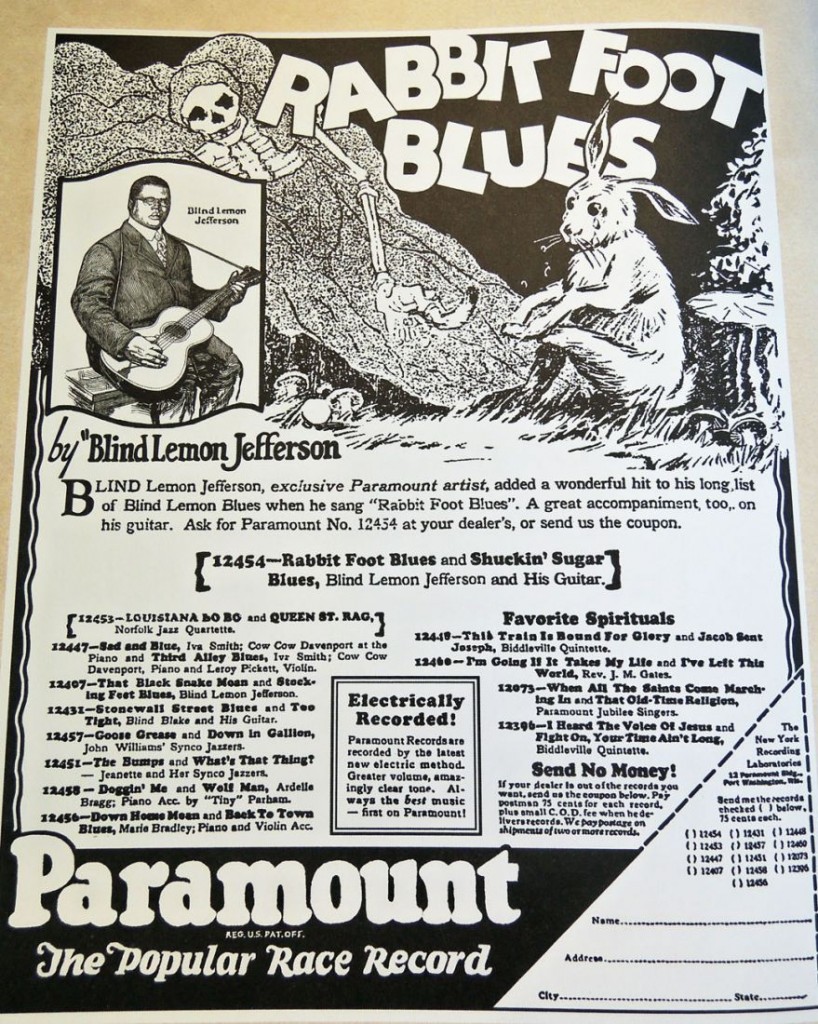

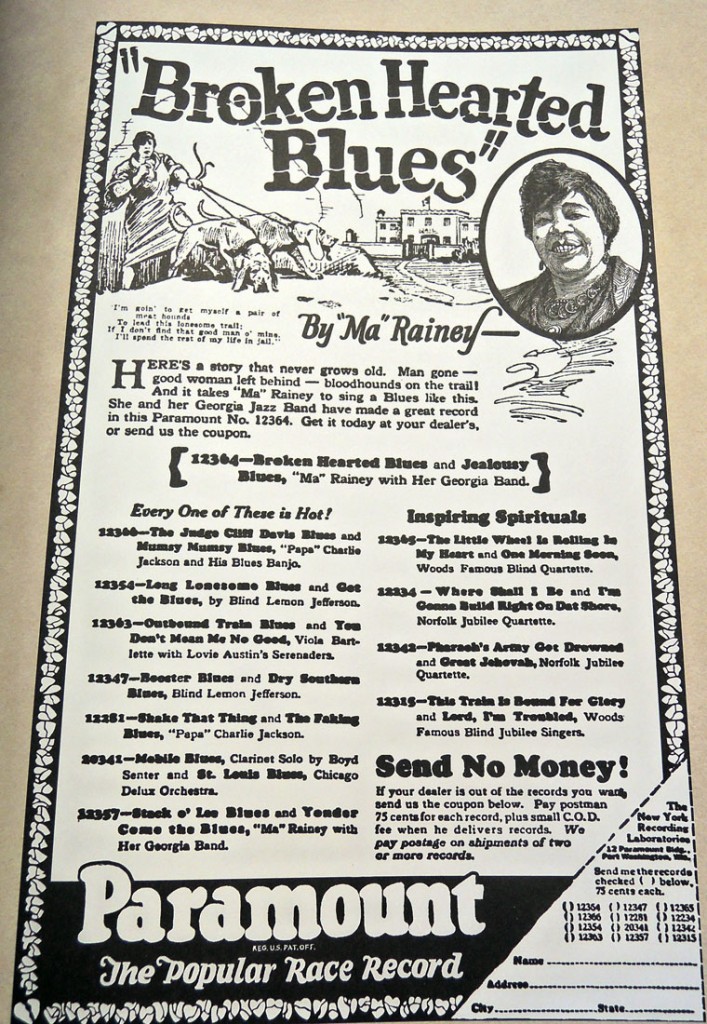

Each ‘cabinet of wonders’ includes 800 newly remastered digital tracks representing over 170 artists; more than 300 fully restored original advertisement from the 1920s-30s; six vinyl records with hand-engraved labels; and two limited edition books including an encyclopedia of artists and tracks as well as a narrative history of Paramount. Volume one is housed in an oak cabinet with a custom-designed USB drive embedded inside and volume two is a stainless steel case also with an embedded drive. Both hold a music & image player app that enables the user personal management of all tracks and advertisements.

Each ‘cabinet of wonders’ includes 800 newly remastered digital tracks representing over 170 artists; more than 300 fully restored original advertisement from the 1920s-30s; six vinyl records with hand-engraved labels; and two limited edition books including an encyclopedia of artists and tracks as well as a narrative history of Paramount. Volume one is housed in an oak cabinet with a custom-designed USB drive embedded inside and volume two is a stainless steel case also with an embedded drive. Both hold a music & image player app that enables the user personal management of all tracks and advertisements.

Quoted from the prospectus: “Paramount Records was formed in 1917 with little fanfare and few prospects its founders ran a Wisconsin furniture company and knew nothing of the record business. Its mission was modest: produce records as cheaply as possible with whatever talent was available. This was not a winning formula, and by the end of 1921 Paramount was on the threshold of bankruptcy.

In 1922 Paramount’s white owners embarked on a radical new business plan: selling the music of black artists to black audiences (a market that became known as “Race Records”). This move, paired with equal parts dumb luck, chicanery, a willingness to try anything, and the fortuitous hiring of Mayo Williams (the first black executive at a white-owned recording company), paid dramatic dividends.

Williams, a Chicago South-sider, early NFL player, bootlegger, impresario, and Brown University graduate, would become a key early champion of those two uniquely American art forms, jazz and blues, while maintaining a not entirely benevolent orientation toward the artists themselves (“screw the artist before he can screw you” being one of his mottoes). Via Williams, Paramount scouted talent, ran the offices of its recording operations, and recorded most of its early records in Chicago, unintentionally playing a documentarian’s role as it captured the very sounds of the Great Migration in the Midwest.

Williams, a Chicago South-sider, early NFL player, bootlegger, impresario, and Brown University graduate, would become a key early champion of those two uniquely American art forms, jazz and blues, while maintaining a not entirely benevolent orientation toward the artists themselves (“screw the artist before he can screw you” being one of his mottoes). Via Williams, Paramount scouted talent, ran the offices of its recording operations, and recorded most of its early records in Chicago, unintentionally playing a documentarian’s role as it captured the very sounds of the Great Migration in the Midwest.

By 1927, Paramount was the most important label in the Race Records field, selling hundreds of thousands of records. And by the time it ceased operations in 1932, it had compiled a dizzying roster of performers still unrivaled to this day by any other assemblage of talent ever housed under one roof spanning early jazz titans (Louis Armstrong, King Oliver, Jelly Roll Morton, Fletcher Henderson, Fats Waller, James P. Johnson, Coleman Hawkins), vaudevillian songsters (Papa Charlie Jackson, The Hokum Boys), the first solo guitar bluesmen (Blind Lemon Jefferson, Blind Blake), theater blues divas (Ma Rainey, Alberta Hunter, Ethel Waters), gospel (Norfolk Jubilee Quartette, Famous Blue Jay Singers of Birmingham), masters of Mississippi blues (Charley Patton, Son House, Skip James, Tommy Johnson), and others.”