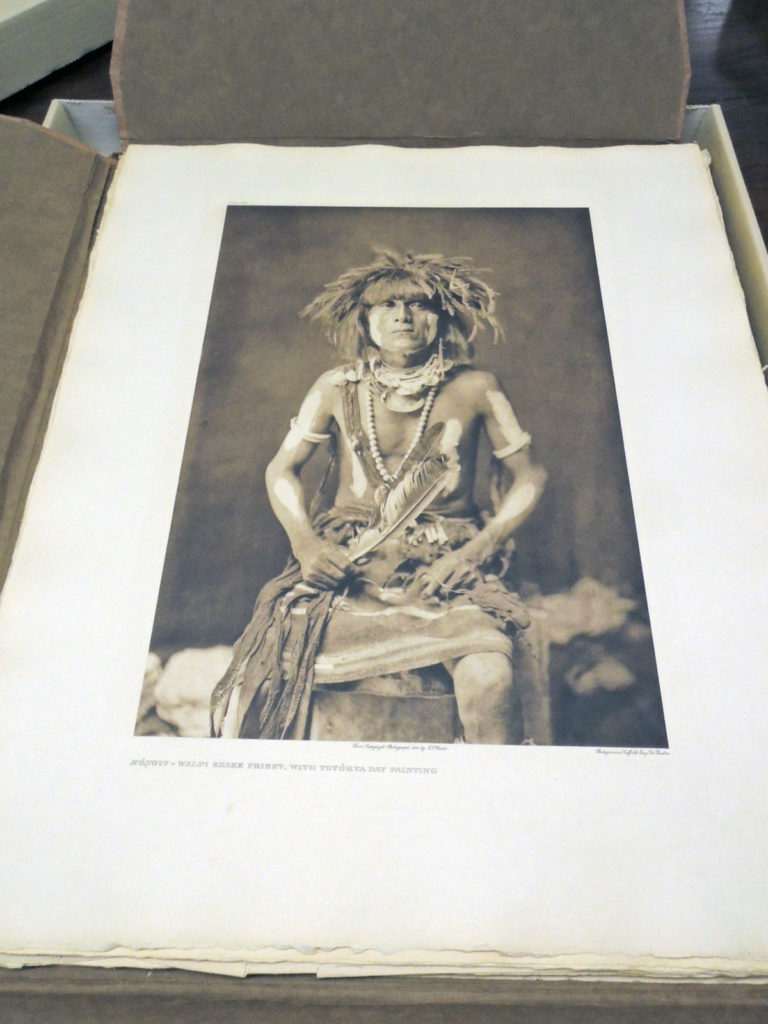

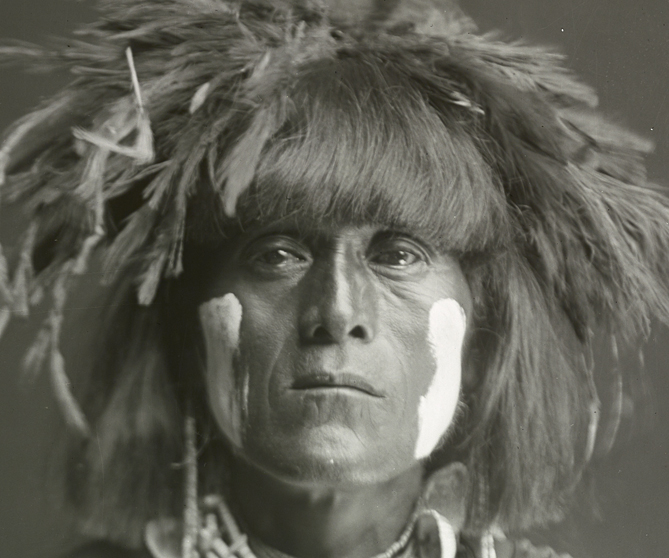

Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952), “Honovi-Walpi Snake Priest, with Totkya Day Painting” from The North American Indian, 1907-1930. Suppl. v. 12, pl. 408. Rare Books EX Oversize 1070.279e

Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952), “Honovi-Walpi Snake Priest, with Totkya Day Painting” from The North American Indian, 1907-1930. Suppl. v. 12, pl. 408. Rare Books EX Oversize 1070.279e

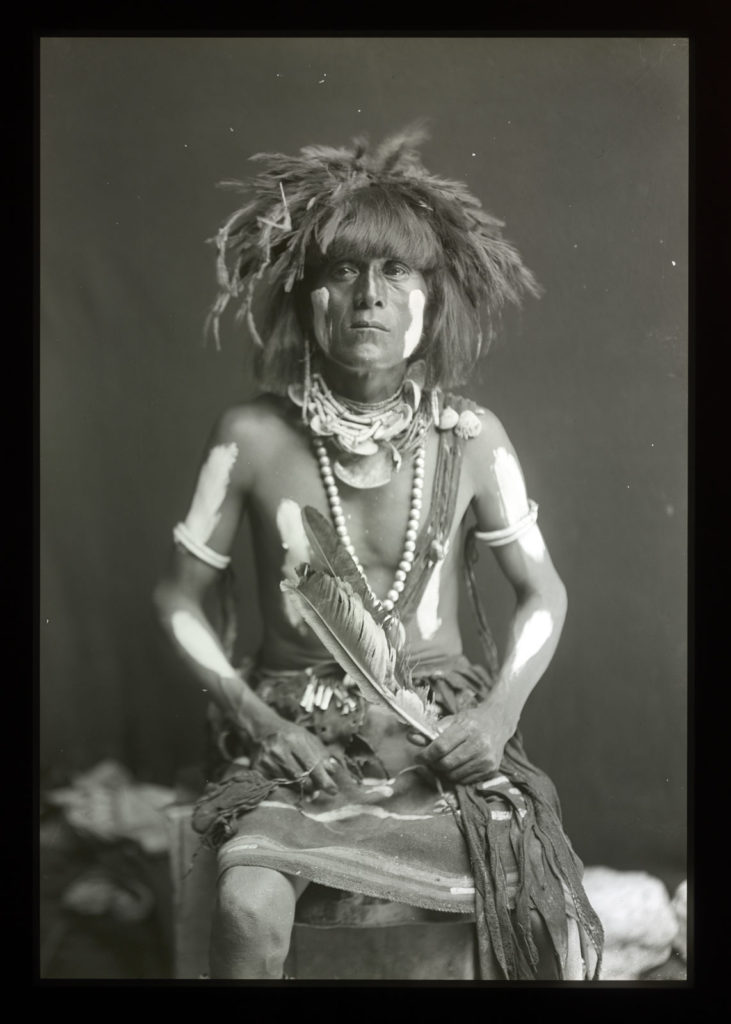

Suffolk Engraving Company after negative by Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952), “Honovi-Walpi Snake Priest, with Totkya Day Painting.” Original glass interpositive prepared for Edward S. Curtis’s The North American Indian, 1907-30, Suppl. v. 12, pl. 408 ([Boston: s.n., ca. 1910]). 39 x 27 cm., housed in light box 57 x 49 x 5 cm. Graphic Arts Collection Vault B glass.

Now available: https://dpul.princeton.edu/catalog/dv13zx94d#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0&xywh=-16011%2C-1%2C38853%2C9573

When you make a classic photogravure, the first step is to convert the photographic negative into a photographic positive. This is transferred to carbon tissue that is attached to the copperplate and from there, you proceed with the complex creation of an aquatint (intaglio ink print on paper). Negative – positive – negative – positive. The positive is also laterally reversed because the final paper will be face down on the copperplate.

It is easy to forgot that for every negative that Edward Curtis prepared, someone had to print it again as a glass positive before the image could be moved onto the copperplate for etching. It is still an open question whether these interpositives were created on the West Coast or, more likely, in Boston where the Suffolk Engraving Company finished the job with a beautiful photogravure print. See also: https://graphicarts.princeton.edu/2018/06/05/who-printed-the-north-america-indian/

A little history from Jon Goodman: http://jgoodgravure.com/about.html

Richard Benson’s explanation: https://printedpicture.artgallery.yale.edu/videos/flat-plate-photogravure [worth every minute]

We have acquired the glass interpositive for plate 408, the Honovi-Walpi Snake Priest portrait and the digital version will soon be available online so you download it. The longer we work with the positive, the more impressed we are with the detail, tonality, and depth of Curtis’s photograph.

Edward Curtis was one of the most important American artists of the nineteenth century and the most celebrated photographer of North American Indians. Over the course of thirty-five years, Curtis took tens of thousands of photographs of Indians from more than eighty tribes. “Never before have we seen the Indians of North America so close to the origins of their humanity, their sense of themselves in the world, their innate dignity and self-possession” (N. Scott Momaday). Curtis’s photographs are “an absolutely unmatched masterpiece of visual anthropology, and one of the most thorough, extensive and profound photograph works of all time” (A. D. Coleman).

Curtis had the Boston firm print 2200 of his images as photogravures for his magisterial The North American Indian, which was hailed as “the most gigantic undertaking in the making of books since the King James Bible” (New York Herald). He devoted the 12th volume to the Hopi, writing of this photograph, “This plate depicts the accoutrement of a Snake dancer on the day of the Antelope dance. The right hand grasps a pair of eagle-feathers – the ‘snake whip’ – and the left a bag of ceremonial meal. Honovi was one of the author’s principal informants.” Curtis’s lifelong project was inspired by his reflection that “The passing of every old man or woman means the passage of some tradition, some knowledge of sacred rite possessed by no other; consequently, the information that is to be gathered, for the benefit of future generations, respecting the modes of life of one of the greatest races of mankind, must be collected at once or the opportunity will be lost for all time.”

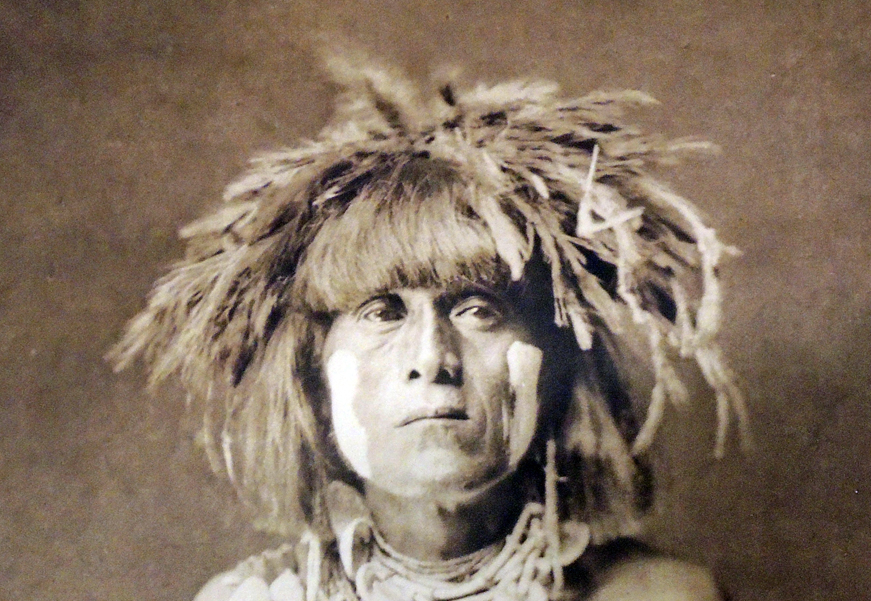

Detail of glass interpositive.

Detail of glass interpositive.