On February 13, 1929, an unidentified Princeton student noted the gift of a book to the university library with an article in the Daily Princetonian, “Parson Weems, First American Book Agent, Subject of Biography Presented to Library.”

On February 13, 1929, an unidentified Princeton student noted the gift of a book to the university library with an article in the Daily Princetonian, “Parson Weems, First American Book Agent, Subject of Biography Presented to Library.”

“First American book agent, adventurer, early biographer of Washington ‘and fabricator of the cherry-tree myth, Parson Weems is the subject of ‘a set of privately issued books presented to the Library last week by Emily Ellworth Ford Skeel, who has completed the work commenced by her brother, Paul Leicester Ford. …Mason Locke Weems, known as the “Parson”, lived a colorful life during the early days of the republic. Having just completed his theological training he went, upon the close of the Revolutionary War, to England to be ordained. The Archbishop of Canterbury refused to “touch the rebel.” He journeyed from one bishop to another fruitlessly. Finally, upon the personal intervention of President Adams, , the Church of Denmark agreed to admit him to the ministry.”

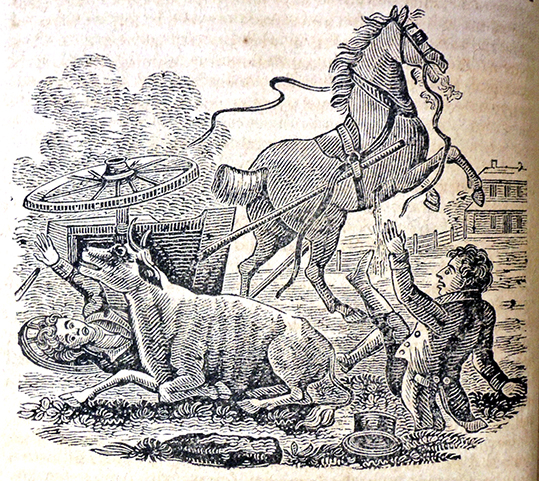

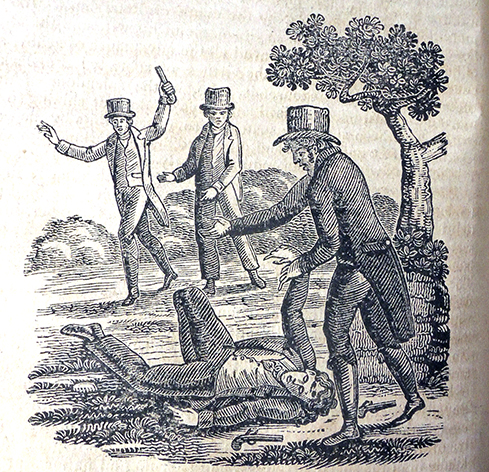

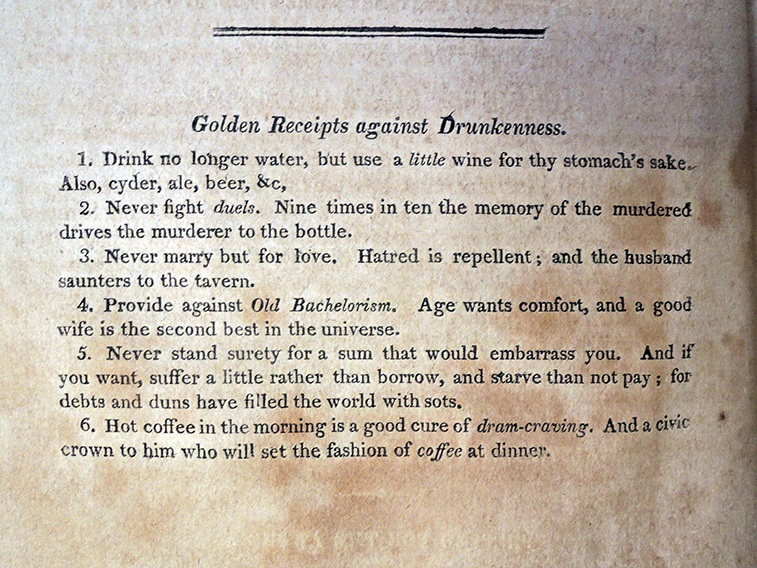

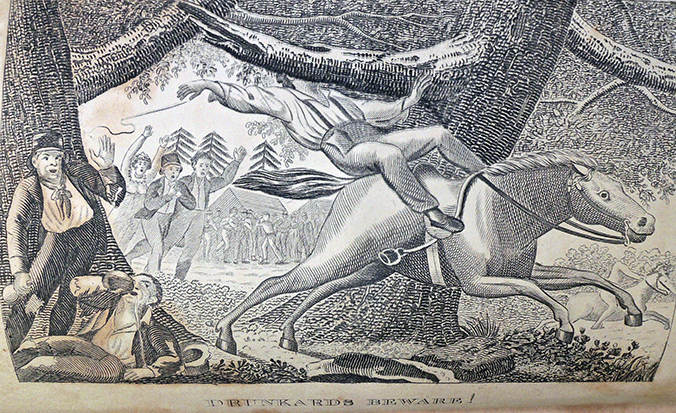

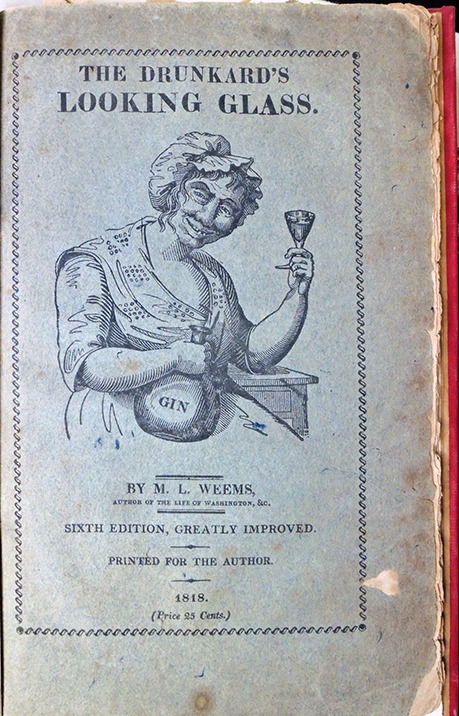

The student continued writing about individual books Weems self-published. “Tiring of [the ministry], he undertook to sell books for Mathew Carey, a Philadelphia publisher. …He saw a market for something besides the holy book, however and filled; it with moral pamphlets of his own composition. One was “The Drunkard’s Looking Glass, reflecting him in sundry very interesting attitudes.” He would enter the taverns illustrating ‘the “attitudes” which he described as follows: “First, when he has only a drop in his eye, second, when he is only half shaved, third, when he is getting a little on the staggers or so, and fourth and fifth and so on ’til he is quite capsized or snug under the table with the dogs and can stick on the floor without holding on.”

Originally written, printed, and published by Weems, the best-selling book continued to appear after his death, privately printed by his wife Mrs. Frances Ewell Weems. Princeton’s 1918 edition was the first to include illustrations, one engraving for the frontispiece “possibly engraved by William Charles,” along with 13 wood engravings attributed to William Mason. Often called the first wood engraver in Philadelphia, Mason is listed as a drawing master at 27 Sansom Street in an 1834 Philadelphia directory and in 1838 another directory listed W.S. Mason at 45 Chestnut.

Mason Locke Weems (1759-1825), The Drunkard’s Looking Glass Reflecting a Faithful Likeness of the Drunkard, in sundry very interesting attitudes, with lively representations of the many strange capers which he cuts at different stages of his disease … Sixth edition, greatly improved ([Philadelphia?]: printed for the author, 1818). Graphic Arts Collection Sinclair Hamilton 1019

Mason Locke Weems, his works and ways. In three volumes. [I] A bibliography left unfinished by Paul Leicester Ford. [II-III. Letters 1784-1825] Edited by Emily Ellsworth Ford Skeel (New York, 1929). Rare Books Z8962 .S62. Colophon of vol. III: This work originated with Paul Leicester Ford, was edited by Mrs. Roswell Skeel junior, and printed by Richmond Mayo-Smith, all of one family.

Reverend Mason L. Weems was rector of Pohick Church for a while, when Washington was a parishioner. He was possessed of considerable talent, but was better adapted for “a man of the world” than a clergyman. Wit and humor he used freely, and no man could easier be “all things to all men” than Mr. Weems. His eccentricities and singular conduct finally lowered his dignity as a clergyman, and gave rise to many false rumors respecting his character. He was a man of great benevolence, a trait which he exercised to the extent of his means. A large and increasing family compelled him to abandon preaching for a livelihood, and he became a book agent for Mathew Carey. In that business he was very successful, selling in one year over three thousand copies of a high-priced Bible. He always preached when invited, during his travels; and in his vocation he was instrumental in doing much good, for he circulated books of the highest moral character.”—Benson J. Lossing, Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution (1850)