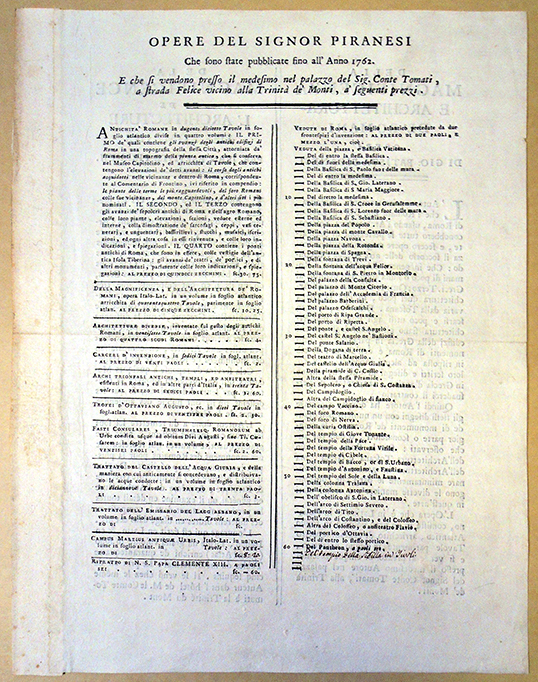

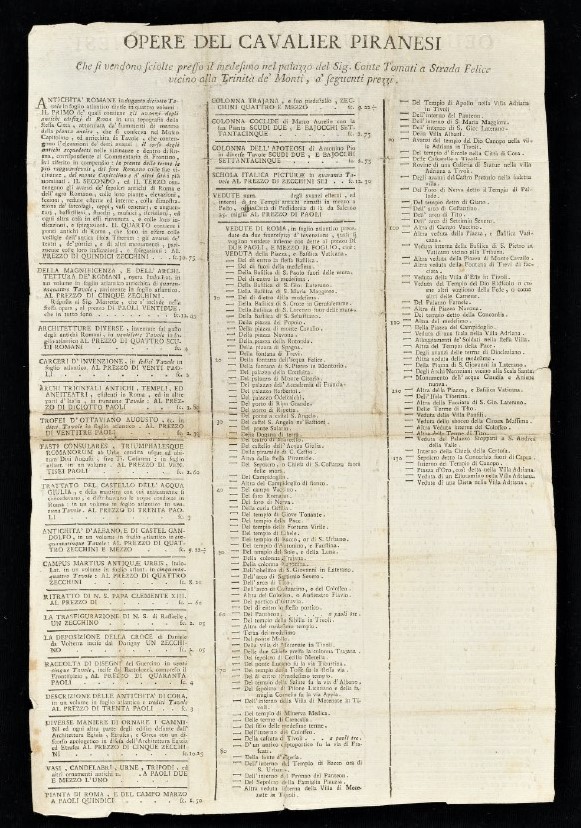

Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778), Opere del signor Piranesi: che sono state pubblicate fino all’anno 1762. E che si vendono presso il medesimo nel palazzo del sig. conte Tomati, a strada Felice vicino alla Trinità de’ Monti, a’ seguenti prezzi (Roma: Piranesi, 1762). 1 letterpress sheet, Italian and French. 31 x 21 cm. Graphic Arts Collection.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778), Opere del signor Piranesi: che sono state pubblicate fino all’anno 1762. E che si vendono presso il medesimo nel palazzo del sig. conte Tomati, a strada Felice vicino alla Trinità de’ Monti, a’ seguenti prezzi (Roma: Piranesi, 1762). 1 letterpress sheet, Italian and French. 31 x 21 cm. Graphic Arts Collection.

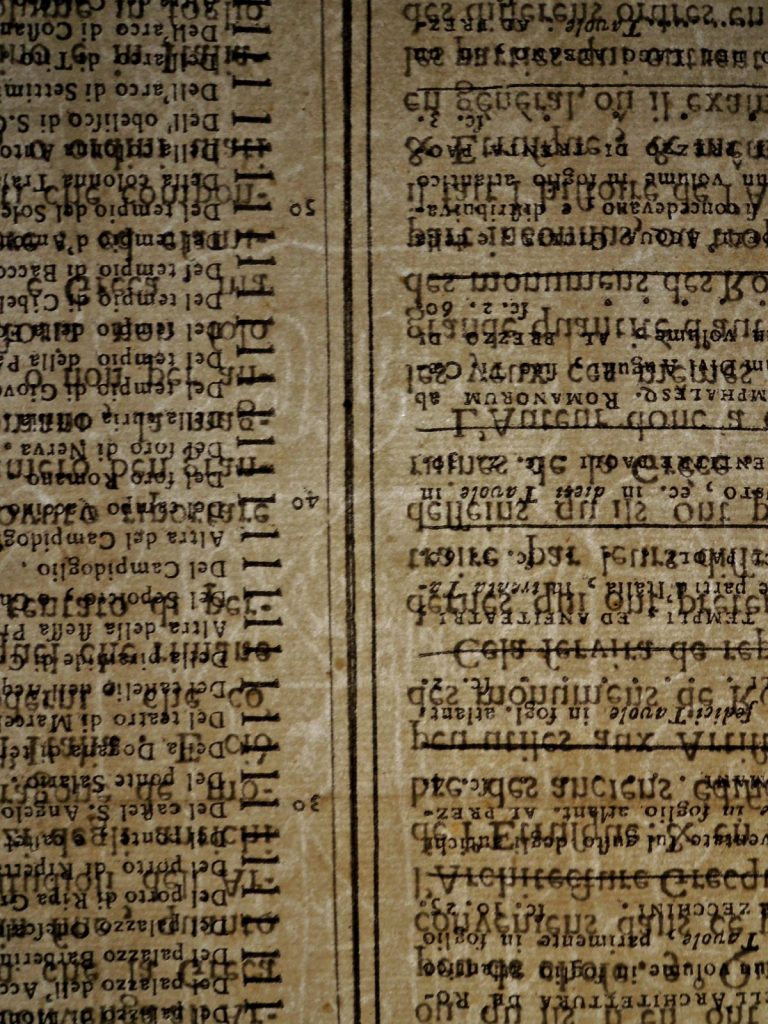

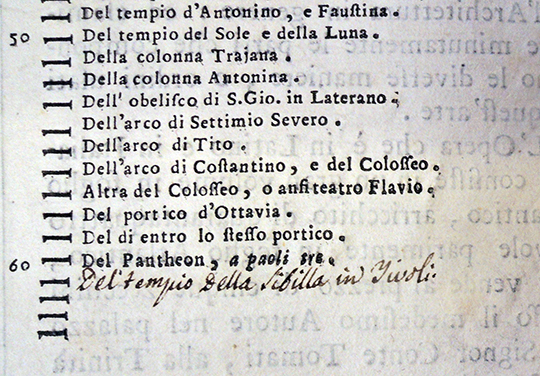

The Graphic Arts Collection is fortunate to have acquired an early printed catalogue of works published “until the year 1762” by Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Making it even more of a treasure is a handwritten addition (presumably Piranesi’s own hand) in the right column list of the “Views of Rome” up to n. 60 “Del Pantheon, paoli tre.” The following view “Del Tempio della Sibilla in Tivoli” [“Of Sibyl’s Temple in Tivoli”] has been added in manuscript.

This catalogue is not unlike the later sheet in the collection of the Getty Research Institute. Each catalogue, at Princeton and the Getty, has text in Italian and French to expand Piranesi’s audience and hopefully his sales. Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778), Opere del cavalier Piranesi: che si vendono sciolte il medismo nel palazzo del. Sig. Conte Tomati a strada Felice … [Rome : G. Piranesi, 1778?]. 1 letterpress sheet, Italian and French; 33 x 22 cm. Getty Research Institute

Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778), Opere del cavalier Piranesi: che si vendono sciolte il medismo nel palazzo del. Sig. Conte Tomati a strada Felice … [Rome : G. Piranesi, 1778?]. 1 letterpress sheet, Italian and French; 33 x 22 cm. Getty Research Institute

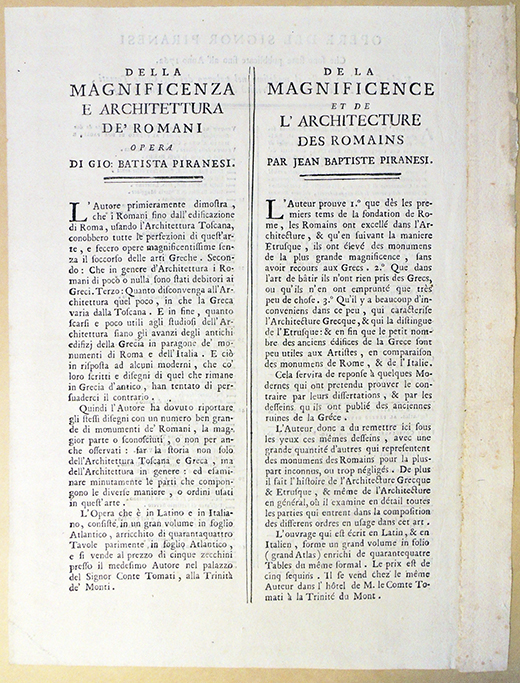

Whether or not Piranesi studied printmaking in Venice, it is certain that soon after his arrival in Rome in 1740, he apprenticed himself briefly to Giuseppe Vasi, the foremost producer of the etched views of Rome that supplied pilgrims, scholars, artists, and tourists with a lasting souvenir of their visit. Quickly mastering the medium of etching, Piranesi found in it an outlet for all his interests, from designing fantastic complexes of buildings that could exist only in dreams, to reconstructing in painstaking detail the aqueduct system of the ancient Romans. The knowledge of ancient building methods demonstrated by Piranesi’s archaeological prints allowed him to make a name for himself as an antiquarian—his Antichità Romane of 1756 won him election to the Society of Antiquarians of London. . . . Given his admiration for Rome and his contentious nature, Piranesi could hardly refrain from entering into the debate at mid-century over the relative merits of Greek and Roman art. Here, too, etching served him well as a means of supporting his arguments. His Delle magnificenza ed architettura de’ Romani of 1761 advanced the view, shared by other scholars, that the Romans had learned not from the Greeks—as British and French scholars had begun to argue—but from the earlier inhabitants of Italy, the Etruscans. Piranesi used his knowledge of ancient engineering accomplishments to defend the creative genius of the Romans, but devoted even more space to a celebration of the richness and variety of Roman ornament. — Thompson, Wendy. “Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778)”. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/pira/hd_pira.htm (October 2003)

We have not been able to identify the enormous watermark that is nearly the size of the entire sheet. Andrew Robinson notes “Although I have now catalogued over 60 watermarks on different Piranesi papers, I am only tentatively confident about my fixing of their dates.” Hopefully a better image of this new mark can be made, which will lead to further scholarship.

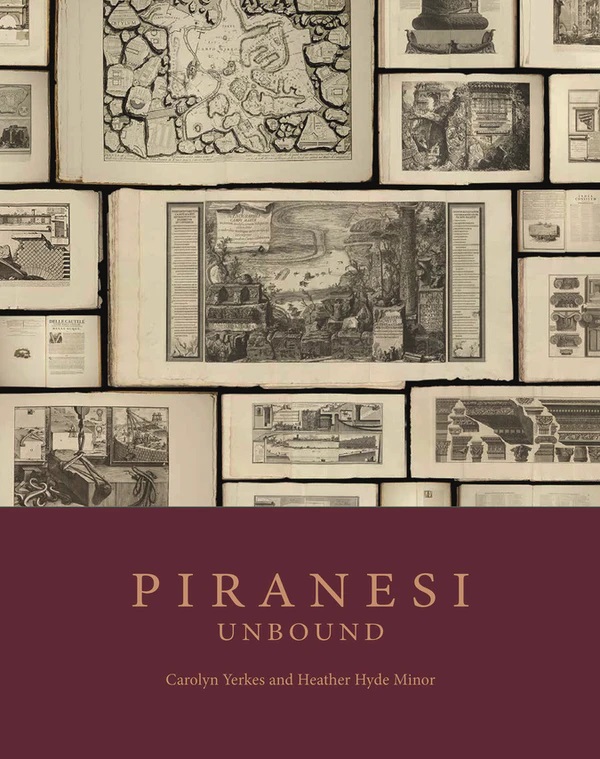

Our sheet will be included this fall in the Firestone Library exhibition, Piranesi on the Page. https://library.princeton.edu/news/general/2020-02-13/puls-upcoming-exhibition-piranesi-page-reveals-art-architects-books. The exhibition is curated by Heather Hyde Minor, professor, University of Notre Dame, and Carolyn Yerkes, associate professor, Princeton University. Piranesi Unbound, a book associated with the exhibition written by the curators, is available from the Princeton University Press.

Our sheet will be included this fall in the Firestone Library exhibition, Piranesi on the Page. https://library.princeton.edu/news/general/2020-02-13/puls-upcoming-exhibition-piranesi-page-reveals-art-architects-books. The exhibition is curated by Heather Hyde Minor, professor, University of Notre Dame, and Carolyn Yerkes, associate professor, Princeton University. Piranesi Unbound, a book associated with the exhibition written by the curators, is available from the Princeton University Press.