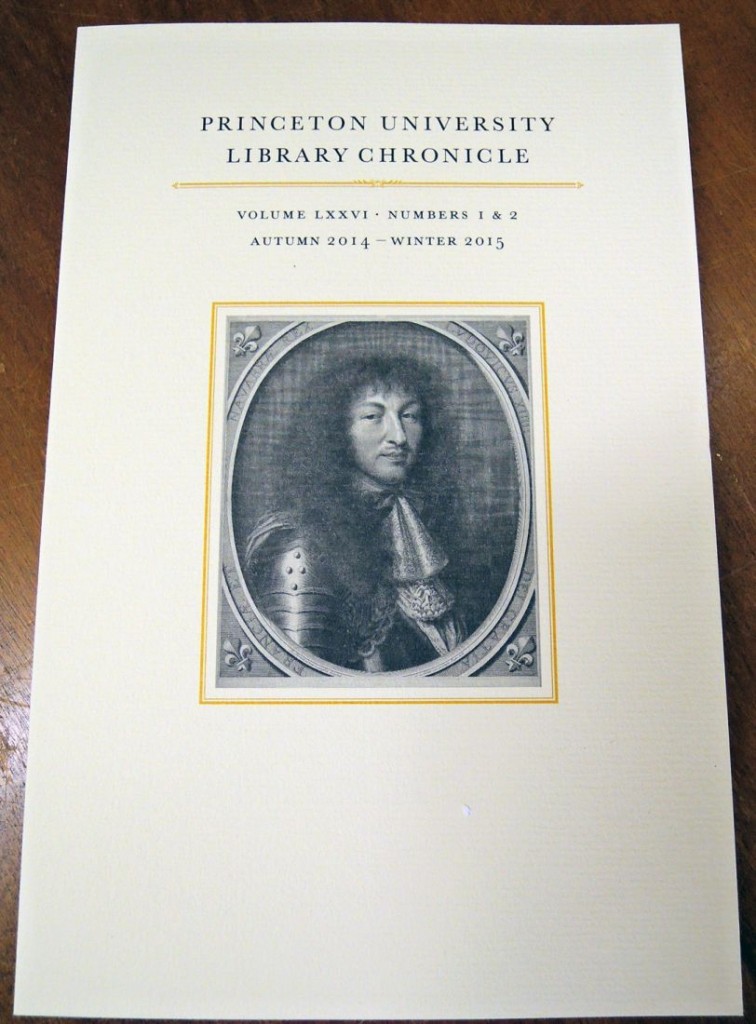

The exhibition “Versailles on Paper: A Graphic Panorama of the Palace and Gardens of Louis XIV,” on view in the Main Gallery of Firestone Library until July 19, 2015, is accompanied by a special double issue of the Princeton University Library Chronicle (Volume LXXVI, numbers 1 & 2, autumn 2014–winter 2015). The volume’s 296 pages offer 8 scholarly essays with 77 black and white illustrations.

The exhibition “Versailles on Paper: A Graphic Panorama of the Palace and Gardens of Louis XIV,” on view in the Main Gallery of Firestone Library until July 19, 2015, is accompanied by a special double issue of the Princeton University Library Chronicle (Volume LXXVI, numbers 1 & 2, autumn 2014–winter 2015). The volume’s 296 pages offer 8 scholarly essays with 77 black and white illustrations.

Friends of the Princeton University Library (FPUL) will receive a copy in the mail very soon and others who would like to join the FPUL, can still receive a free copy of the Chronicle with their membership. To join, see: http://www.fpul.org/chronicle/index.html. Single issues are $30 plus postage.

This issue contains the following articles:

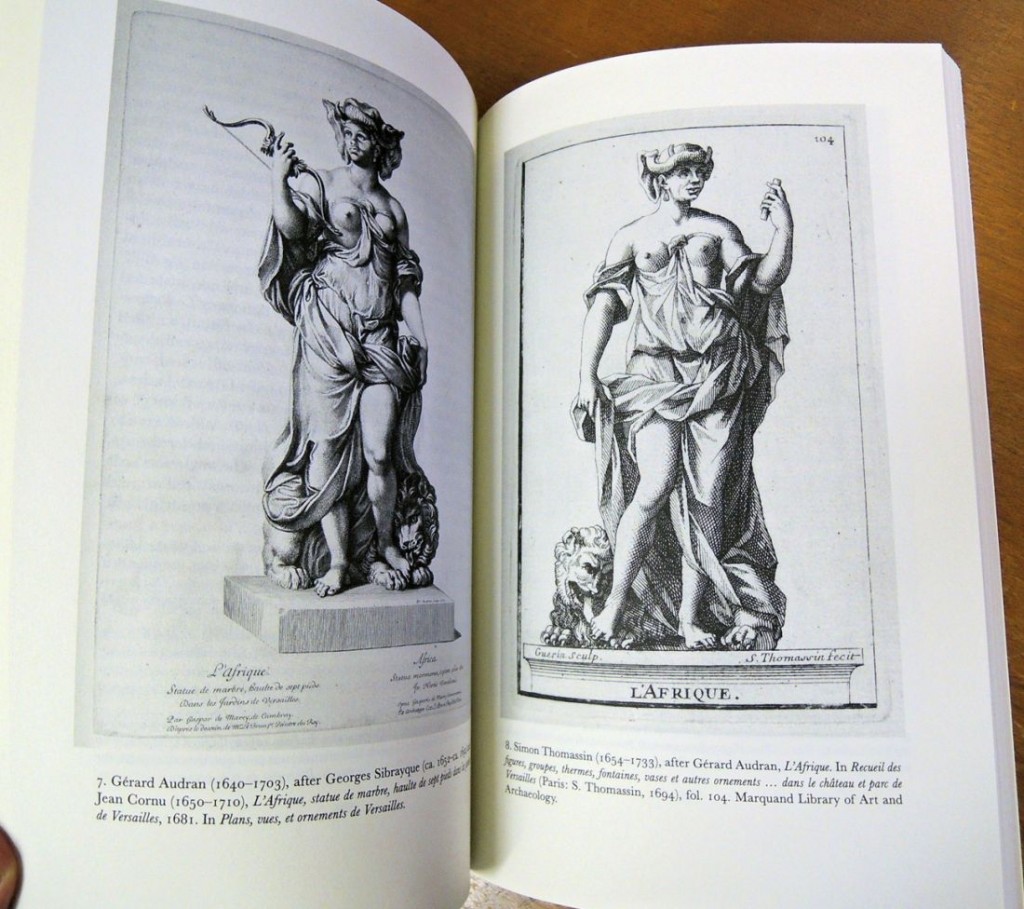

Audrey Adamczak, “Engraving Sculpture: Depictions of Versailles Statuary in the Cabinet du Roi”

This essay examines the presence of the sculpted object in prints that celebrated the treasures of the crown, especially those displayed at Versailles. Sculptures are well represented among the works of art selected to be engraved for the collection known as Cabinet du Roi. The most renowned works, both ancient and modern, were represented for their own sake and not just as secondary subjects. Engravings took various forms, depending upon the model and the printmaker’s technical choices. The goal of this essay is twofold: to analyze the techniques used by individual engravers to reproduce the medium of sculpture and render its effects; and to highlight the value of these prints as a graphic record of the Versailles statuary, much of which has been dispersed, destroyed, or irrevocably altered.

Hall Bjørnstad, “From the Cabinet of Fairies to the Cabinet of the King: The Marvelous Workings of Absolutism”

What do fairy-tale kings have in common with real-life absolute monarchs? If we turn to the case of Jean de Préchac’s 1698 fairy tale about King Sans Parangon (Without Equal), the answer is: quite a bit. An allegorical retelling of the life of Louis XIV, structured according to the whims of an enchanted Chinese princess named Belle Gloire, this tale is often read as mere flattery without any interest beyond the excess of its praise. However, this paper argues that a close analysis of certain key scenes of “Sans Parangon,” especially the one portrayed in the engraving illustrating the second edition of the text in 1717, will bring us surprisingly close to the inner workings of absolutism.

Benoît Bolduc, “Fêtes on Paper: Graphic Representations of Louis XIV’s Festivals at Versailles”

In the three illustrated festival books commemorating the divertissements given by Louis XIV in 1664, 1668, and 1674, Versailles becomes a site for performing monarchical authority. The plates, designed by Israël Sylvestre, Jean Lepautre and François Chauveau, illustrating the equestrian parades, buffets of refreshments, musical entertainments, and pyrotechnical displays offered to the court, showcase the newly designed gardens of Versailles as a decorous and enchanted space where art and nature merge to the point of becoming indistinguishable. The printed account by André Félibien insists on the miraculous nature of the settings and achieves the goals of classical ekphrasis by mimicking the effects produced by the experience of the festival, leading the reader toward the sublime contemplation of the generative power of the French king.

Thomas F. Hedin, “Facts, Sermons, and Riddles: The Curious Guidebook of Sieur Combes”

The Explication historique de ce qu’il y a de plus remarquable dans la maison royale de Versailles, et en celle de Monsieur à Saint Cloud, was published by Laurent Morellet (alias Combes or Sieur Combes) in 1681, a time of euphoria and national pride: the Dutch War had ended, to French advantage, three years earlier; the château and gardens of Versailles were brimming with new works of art; the Grand Dauphin’s recent marriage held high promise of royal progeny. Combes, the chaplain to Monsieur, the King’s brother, was on hand to celebrate the joyous moment. His book contains information on Versailles found nowhere else in the contemporary literature. Offsetting his passion for documentary detail, Combes subjected some of the most prominent statues and fountains to purely fantastic, self-indulgent “explications.” Nor could he resist the temptation to treat the gardens as a pulpit, to lecture his congregation of readers, particularly the ladies of the court, on his notions of Christian morality; he often appeals to his dedicatee, the newly-wed Grande Dauphine. The researcher is advised to tread cautiously through this fascinating, meandering book.

Betsy Rosasco, “The Herms of Versailles in the 1680s”

Following the first set of herms executed for Versailles in the 1660s, and the purchase from Nicolas Fouquet’s son in 1683 of a second set of herms designed by Nicolas Poussin for Vaux-le-Vicomte, the Versailles gardens received a third set of herms, commissioned by the Marquis de Louvois, Surintendant des Bâtiments, beginning in 1684. Consisting of literary figures (Ulysses and Circe), Olympian gods (Jupiter, Juno…), lesser deities (Faun, Bacchante…), and Greek philosophers (Plato, Diogenes…), these understudied sculptures were designed mainly by Pierre Mignard,but in two cases Charles Le Brun and Jules Hardouin-Mansart’s team, and executed by distinguished masters such as Corneille van Clève and Étienne Le Hongre. It is argued that, unlike the earlier herms – expressive of galant or Bacchic themes appropriate to rural surroundings and pleasures – these herms were didactic and intended for the education of the Duc de Bourgogne, the future dauphin of France. Suggestions are advanced about the content of the lessons and the possible use of the sculptures as a Memory Palace.

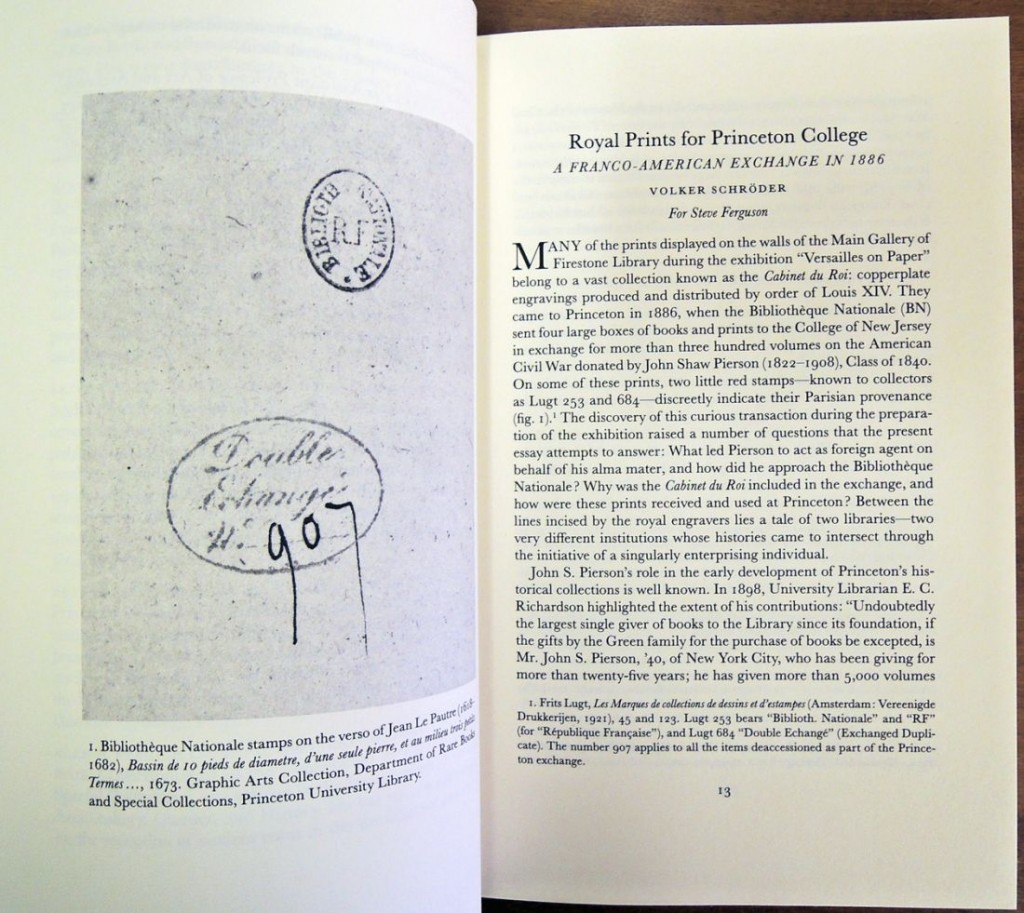

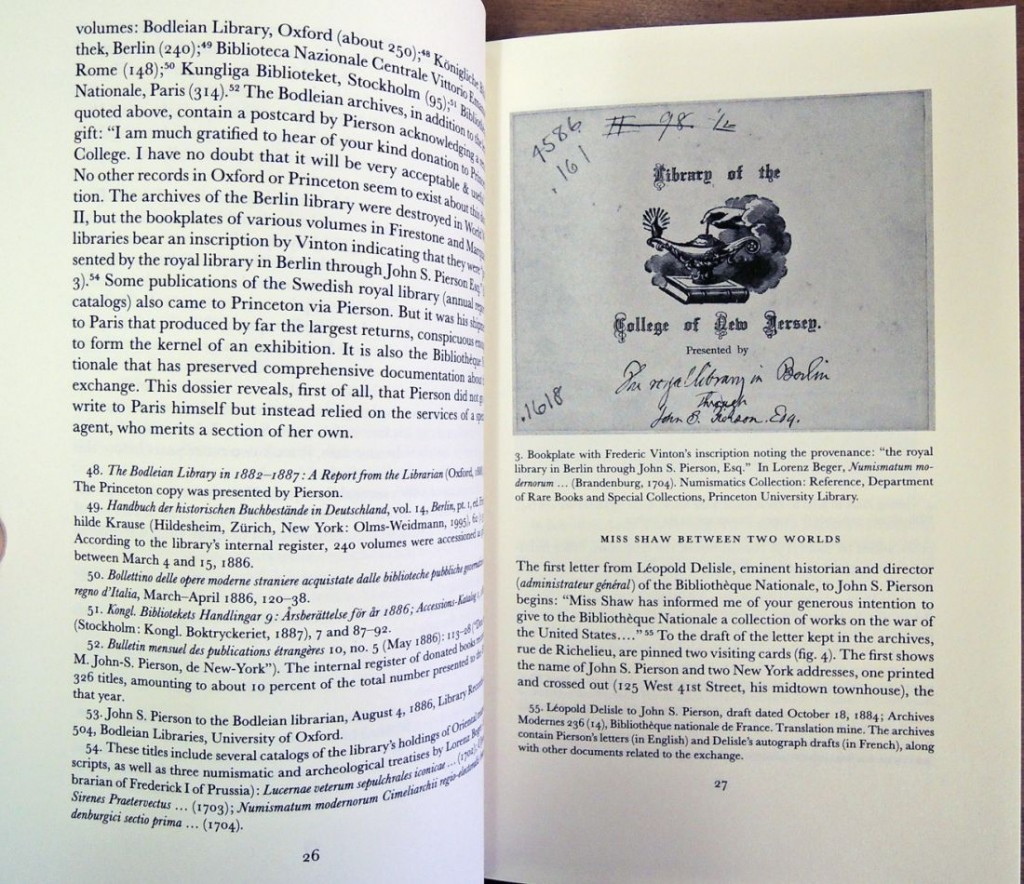

Volker Schröder, “Royal Prints for Princeton College: A Franco-American Exchange in 1886”

Many of the prints displayed on the walls of the main gallery of Firestone Library during the exhibition “Versailles on Paper” belong to a vast collection known as the Cabinet du Roi: copperplate engravings produced and distributed by order of Louis XIV. They came to Princeton in 1886, when the Bibliothèque Nationale sent four large boxes of books and prints to the College of New Jersey in exchange for more than three hundred volumes on the American Civil War donated by John Shaw Pierson (1822–1908), Class of 1840. The discovery of this curious transaction during the preparation of the exhibition raised a number of questions that the present essay attempts to answer: What led Pierson to act as foreign agent on behalf of his alma mater, and how did he approach the Bibliothèque Nationale? Why was the Cabinet du Roi included in the exchange, and how were these prints received and used at Princeton? While John S. Pierson’s role in the early development of Princeton’s historical collections is well known, the 1886 exchange with the Bibliothèque Nationale (and other European libraries) has been all but forgotten. It deserves to be brought back to light and calls for a broader reassessment of Pierson’s purpose as a collector and benefactor.

Alan M. Stahl, “The Classical Program of the Medallic Series of Louis XIV”

In the preface to the 1702 deluxe folio edition of the Médailles sur les principaux événements du règne de Louis le Grand, avec des explications historiques, the Abbé Paul Tallemant set out the purpose and procedures underlying the production of the volume and the medallic series which it accompanied. Like many other aspects of the culture of the court of Louis XIV, the medallic series sought both to emulate and surpass the achievements of classical antiquity, in this case the high relief coins produced by the emperors of the first two centuries of the Roman Empire. This article examines the procedures and structures of the Petite Académie (which included Charles Perrault, Jean Racine and Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux), charged with the creation of images and inscriptions for the series, and the extent to which the resulting medals achieved the stated goals and set a pattern for the future of the medium.

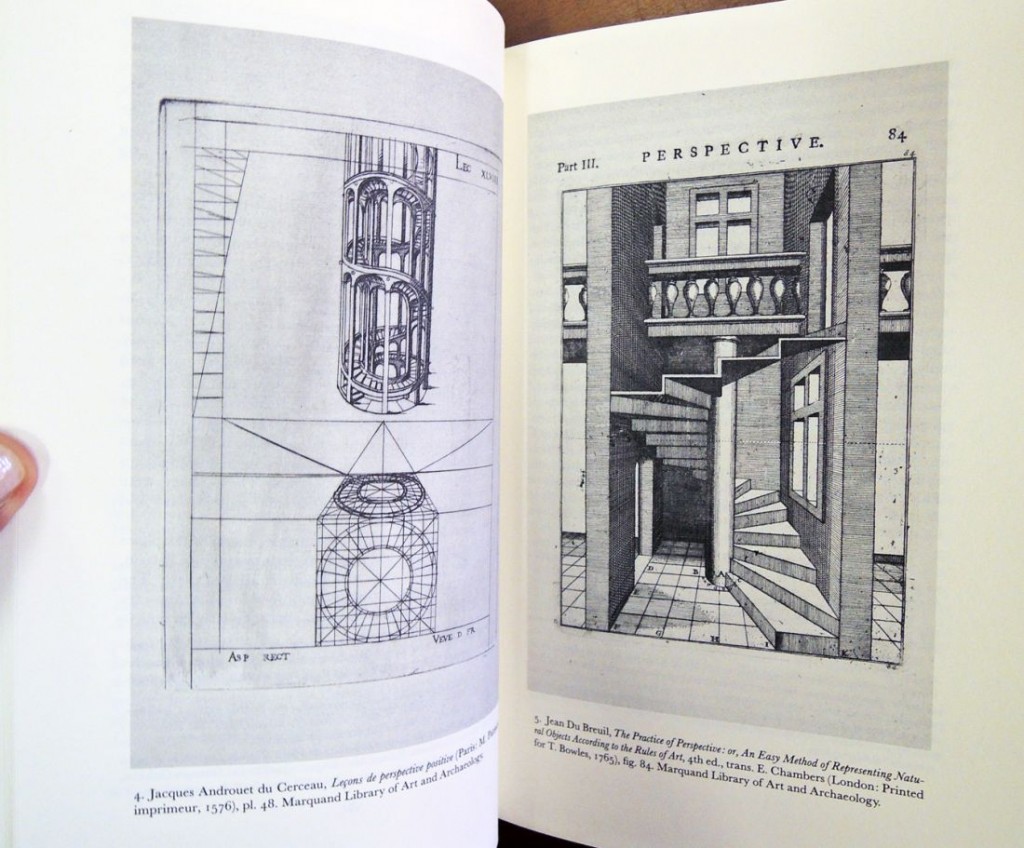

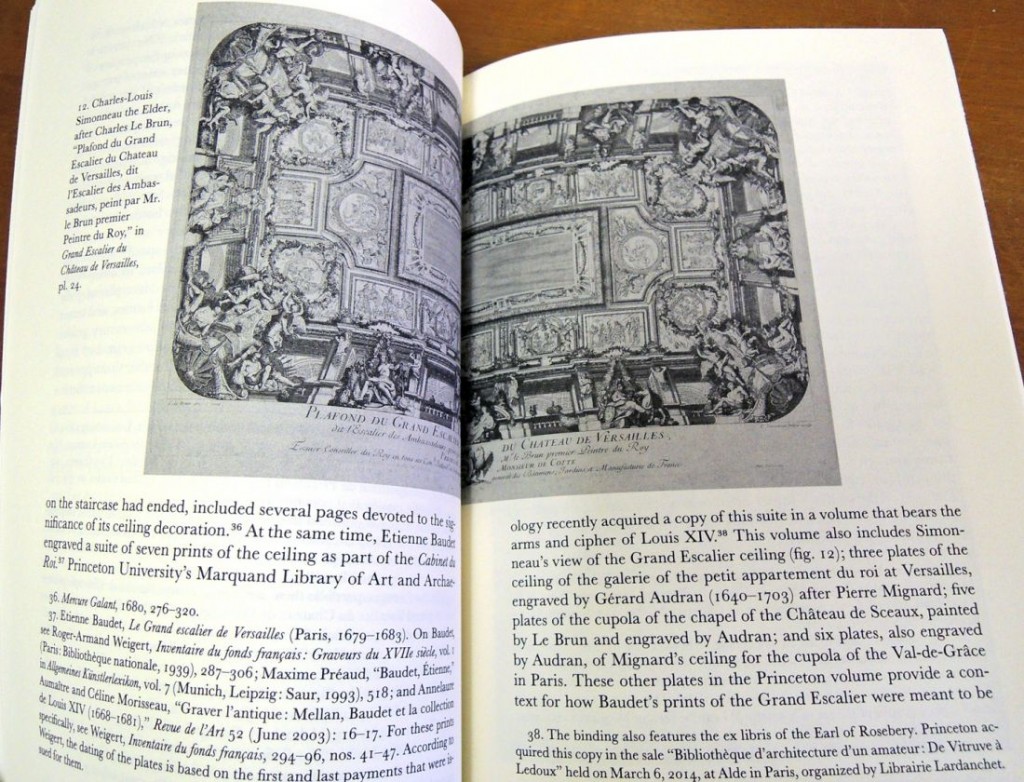

Carolyn Yerkes, “The Grand Escalier at the Château de Versailles: The Monumental Staircase and Its Edges”

The Grand Escalier, also called the Grand Degré or the Escalier des Ambassadeurs, is one of the most significant architectural elements to have disappeared from the château of Versailles. Completed in 1679, this element had a hybrid function: not only was it the principal staircase of the palace, the primary means of access to the state rooms on the second floor, but it also was the official reception point for foreign dignitaries and thus a ceremonial space in its own right. The Grand Escalier was meant to be a tour de force, a display of architectural bravado that combined a relatively new form of staircase design with a lavish decorative treatment. Yet despite its spatial and functional importance, the staircase was short-lived, destroyed in 1752 under Louis XV. Its particulars are known mainly from seventeenth- and eighteenth-century prints that detail every aspect of its original appearance. These prints of the Grand Escalier mark the intersection of two trajectories in French architectural theory: the representation of the staircase as a demonstration of technical achievement and the representation of the interior as an essential component of planning and design. The prints demonstrate how the Grand Escalier departed from the Renaissance tradition of the showpiece staircase, a tradition in which a staircase’s independence from the wall as a means of support became a sign of structural daring. Instead, the Grand Escalier’s virtuosity is the way it merges with the wall, effectively incorporating the inhabitants of the room as the final elements of a complex decorative program.

Our thanks to the Friends of the Princeton University Library for their support of exhibitions and publications celebrating the superb materials in Princeton’s Rare Books and Special Collections.