In James Kirkup’s 1993 obituary for the French/Cuban artist and writer Severo Sarduy (1937-1993), he writes:

“When Castro came to power, Sarduy wangled a grant to study art in Paris. His talent as a painter and designer was to accompany his writing throughout his life, and at the time of his death he was planning a vast retrospective of his paintings and drawings in Madrid. He never returned to Cuba, though he always felt anguished nostalgic longings to do so. At 23, he at once felt at home in the city that has welcomed so many Spanish and Latin American refugees from Fascist and Communist butchery. He never considered himself an exile or an immigrant: ‘I am a Cuban through and through, who just happens to live in Paris.’ Nevertheless, he became a French citizen in the Seventies.”

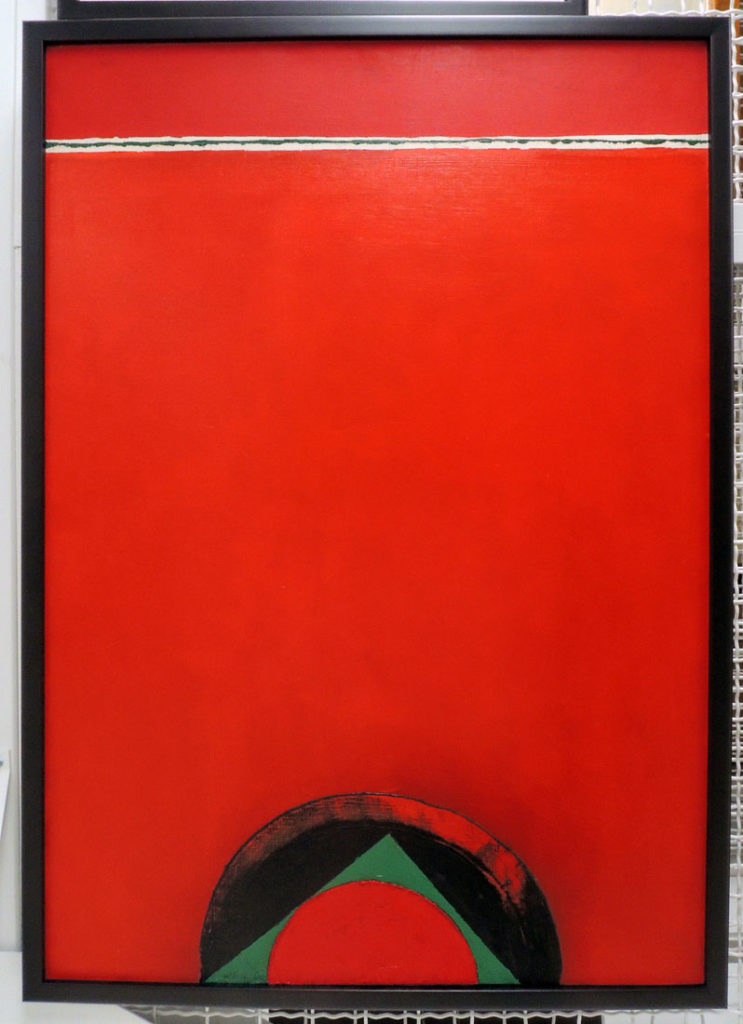

Thanks to Sarduy’s partner François Wahl (1925-2014), a small group of Sarduy’s canvases and works on paper are held in the Graphic Arts Collection. Created with unusual mediums including coffee and fingernail polish, many were in need to conservation and repair. Thanks to the Gratz Gallery & Conservation Studio, ten works have been conserved, re-framed, and are now once again, available for researchers here in Firestone Library.

When first in Paris, Sarduy attended Roland Barthes’ seminars on language at the College de France, and his collection included works on paper by Barthes, now also at Princeton University.

His last book, Christ on the Rue Jacob; translated by Suzanne Jill Levine and Carol Maier (Firestone Library PQ7390.S28 C713 1995) was reviewed in Publisher’s Weekly:

His last book, Christ on the Rue Jacob; translated by Suzanne Jill Levine and Carol Maier (Firestone Library PQ7390.S28 C713 1995) was reviewed in Publisher’s Weekly:

This truly beautiful book is the last by the Cuban-born, Paris-nurtured writer who died in 1993 of AIDS. In a collection of brief, even minute, essays, he offers maps to the passage of time. The first such map is his body, on which ‘epiphanies’ are marked by scars-beginning with the navel, the first wound. The second map is Sarduy’s mind, filled with sharp impressions of places (Cafe de Flore, Benares) and people (Roland Barthes, Italo Calvino). It can make for lonely reading, in part because many friends (Barthes and Calvino among them) are dead.

In ‘The Tibetan Book of the Dead,’ Sarduy recounts the changes in his address book as death threatens to turn it into a ‘novel, or biographical fiction.’ But, facing his own death, Sarduy refuses to remove the name of a dead friend because ‘it would be like eradicating him all over again, as if I were an accomplice of the void, subjecting him to another death within death’.