Preparing for a visit from ART 561/ENG 549/FRE 561 “Painting and Literature in Nineteenth-Century France and England,” the prints of Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz) for Charles Dickens’ Bleak House have been pulled. Phiz completed forty plates, etched on steel, for Dickens’ ninth novel published in monthly parts from March 1852 to September 1853.

Preparing for a visit from ART 561/ENG 549/FRE 561 “Painting and Literature in Nineteenth-Century France and England,” the prints of Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz) for Charles Dickens’ Bleak House have been pulled. Phiz completed forty plates, etched on steel, for Dickens’ ninth novel published in monthly parts from March 1852 to September 1853.

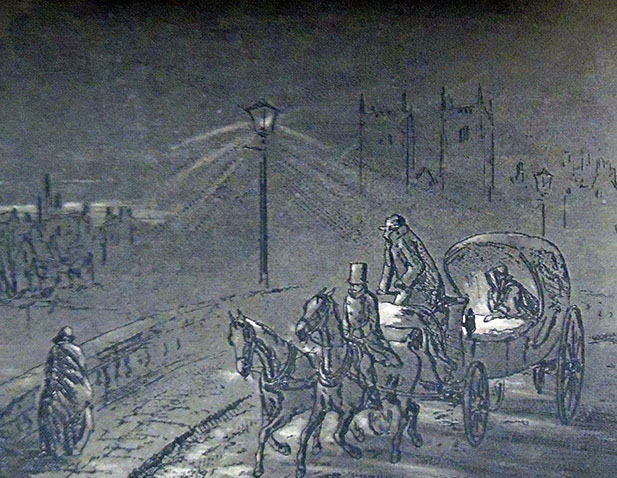

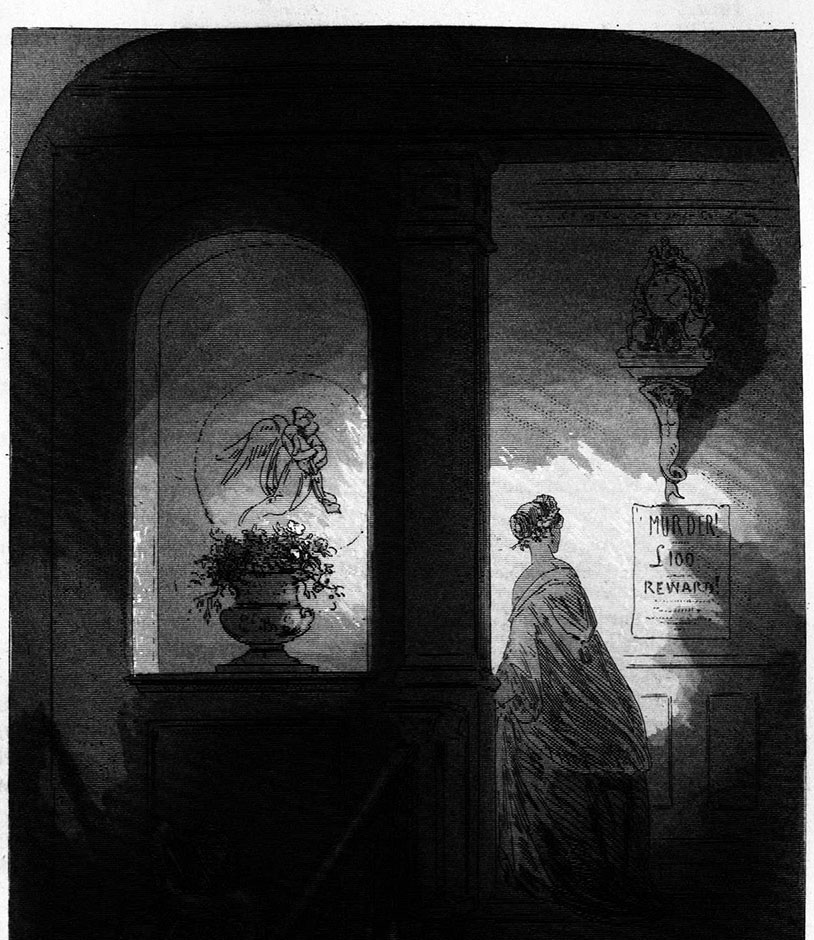

Both for the added mystery and to thwart the lithographers who made copies of Browne’s superb etchings, the artist developed a technique for what we refer to as the ‘dark plates.’

In ten of the forty illustrations, Browne merged the meticulous engraved lines made by an engraving- or ruling-machine with the hand drawn lines of his etching needle to create the look of a mezzotint with the detail and freedom of a drypoint.

Engraving on steel had only recently been perfected. In 1895, C. W. Dickinson wrote an easy to understand description of “Copper, steel and bank-note engraving,” quoted here:

“Previous to the year 1830 only copper plate was used by engravers, because up to that time it was not thought possible to make steel soft enough to cut easily and smoothly. The first plate produced—that could be used—was called “silver steel.” Later there was manufactured the “Prussian steel” plate, which was a slight improvement in fineness of grain. Other and greater improvements followed, until now steel has almost entirely superseded copper.

Decarbonated cast steel is used for general engraving purposes and must be of very fine grain, and very soft as compared with natural cast steel. The plates are rolled out from bars of steel in its natural state, then decarbonated and cut to about the size desired, leaving enough margin to square the edges, which are finished with a wide bevel. After the plate has been cut to size, it is flattened by laying it upon a copper anvil and hammering with a wooden mallet until it is as flat as is possible to get it by that process. A uniform thickness and perfectly flat surface are then given to the plate by grinding—sometimes by hand, usually by machine—the latter process being the better, as it is the more perfect in its results.”

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Popular_Science_Monthly/Volume_46/March_1895/Copper,_Steel,_and_Bank-Note_Engraving

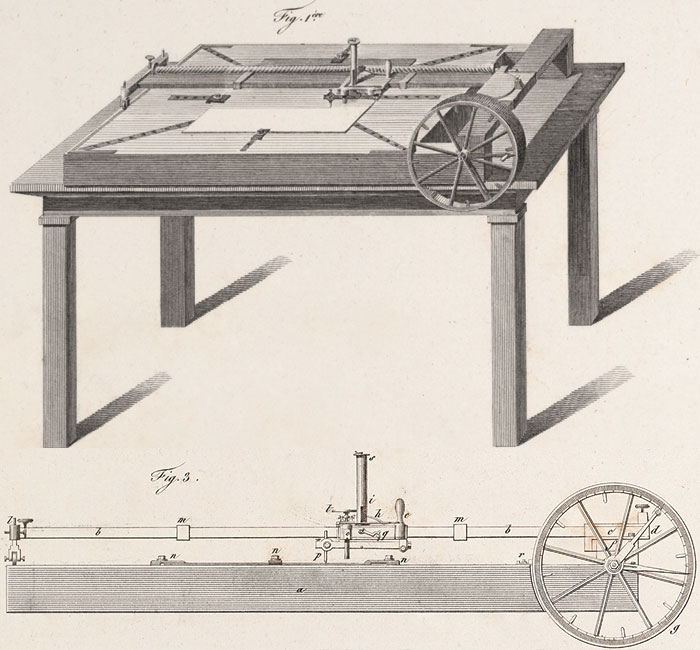

Also in the early 19th-century ruling machines for engravers were being up-graded, in particular to accommodate enormous publishing project such as Napoleon’s Description de l’Égypte. As improved and enhanced by Nicolas Conté, the French engraving machine was invaluable for the thousands of lines incorporated into the skies and landscapes within his designs. Here’s an image: https://napoleon.lindahall.org/engraving.shtml

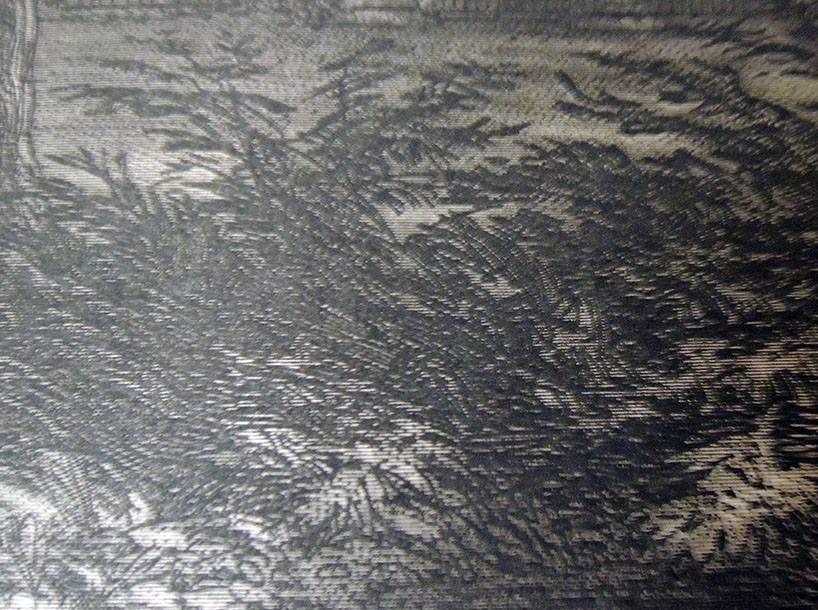

A diamond was often used as the stylist on the engraving machines, hard enough to cut but thin enough to draw the slender marks that left the impression of a tint or tone rather than line. Here are a few close ups that make it easier to see the hundreds of tiny straight lines behind Browne’s linear picture.

A diamond was often used as the stylist on the engraving machines, hard enough to cut but thin enough to draw the slender marks that left the impression of a tint or tone rather than line. Here are a few close ups that make it easier to see the hundreds of tiny straight lines behind Browne’s linear picture.