Late in the fall of 1936, the celebrated author Dashiell Hammett (1894-1961) moved to Princeton, New Jersey, where he rented a mansion [his word] at 90 Cleveland Lane from James Renwick Sloane (1881-1955). He moved in with his Black chauffeur/valet and two dogs named Baby and Pal (sadly Baby died while in Princeton).

Late in the fall of 1936, the celebrated author Dashiell Hammett (1894-1961) moved to Princeton, New Jersey, where he rented a mansion [his word] at 90 Cleveland Lane from James Renwick Sloane (1881-1955). He moved in with his Black chauffeur/valet and two dogs named Baby and Pal (sadly Baby died while in Princeton).

Hammett was immediately invited to address the local elite at the Nassau Club but rather than write a talk, he simply answered questions concerning everything from “Shakespeare to his experiences in Hollywood.” On Christmas day, the sequel After the Thin Man was released to popular acclaim and Hammett was called America’s best-loved writer. Not wanting to continue with the series, in February 1937 Hammett sold M-G-M all rights to The Thin Man title and characters for $40,000.

Later that month he agreed to act as a judge for the Princeton Community Players playwriting contest but on the day the entries were due, Hammett left town. According to his biographer, Richard Layman, he was asked to leave Princeton by his neighbors due to his loud parties, overnight female guests, and drunken students (his recent membership in the Communist Party was not mentioned). Renwick Sloane sued Hammett for damages made to the house, which was soon after torn down and replaced with a new nine-bedroom home in 1940.

In the November 11, 1936, issue of the Daily Princetonian, Henry Dan Piper, class of 1939, wrote an article titled “Dashiell Hammett Flees Night Club Round Succumbing to Rustication in New Jersey”:

In the November 11, 1936, issue of the Daily Princetonian, Henry Dan Piper, class of 1939, wrote an article titled “Dashiell Hammett Flees Night Club Round Succumbing to Rustication in New Jersey”:

Wearied of New York’s sophisticated clatter, the tall, prematurely greying Dashiell Hammett, author of “The Thin Man” and “The Glass Key,” has escaped to the privacy of a rambling, white clapboard farmhouse perched on a hillside outside of Princeton. “This is the life” he sighed, seated in his armchair before a roaring fire, and succumbing to the inquisition of a Princetonian interviewer. “You can get fed plenty cooped up in a three room apartment, making the same rounds every night—Stork Club, 21, Dempsey’s—seeing the same old faces and hearing the same damned chatter. Nuts.” “There isn’t much to tell about me,” he said. “Baltimore as a kid. . . school for a coupla years. . . stevedore . . . newsboy. . . Golly, I’ve seen lots of things, but I never seemed to stick long at ’em. When the Armistice came along, all I could boast was a pair of weak lungs contracted in the Ambulance Corps.”

“I did some private detective work for Pinkerton’s, but all the time I was getting sicker, and found myself shortly in a California hospital. Then it was a case of turning to something to keep the butcher away from the door while I tried to bluff along the baker. So I rented a second-hand typewriter and pounded out my first novel. It was just a case of lucky breaks after that. Yes, I’m working on a book here, but it’s not a mystery, and it’s not about Princeton. I really don’t like detective stories, anyway. I get too tangled up in the plots. This one is just about a family of a dozen children out on an island. You see, all I do in a story is just get some characters together, and then let them get in each other’s way. And let me tell you, 12 kids can sure get in each other’s way!”

Asked if he were indulging in any more stories about the liquor-swilling, sophisticated pent house dwellers of “The Thin Man,” Hammett wrinkled his brow and exclaimed, “I can’t understand why people get the idea all I ever write is artificial, with tinseled-and-ginned up characters. They’re just like lots of people I know neurotics and what have you. “You know, ideas float around that New York and Hollywood people are all nuts. I’ve just come back from working on a new Powell-Loy film and I admit lots of those guys out there are screwy. But, hell, they’ve got tons of money to be screwy with. And anyhow, they’re no more bats than a lot of over-stuffed” executives I’ve had the misfortune to meet. “Yes, it’s going to be like the others,” he said, returning to the new movie. “They say they’re going to call it ‘After the Thin Man.’ Heaven only knows why. Before Hollywood started monkeying with the plot it was something like ‘The Thin Man,’ but its own mother wouldn’t recognize it now.”

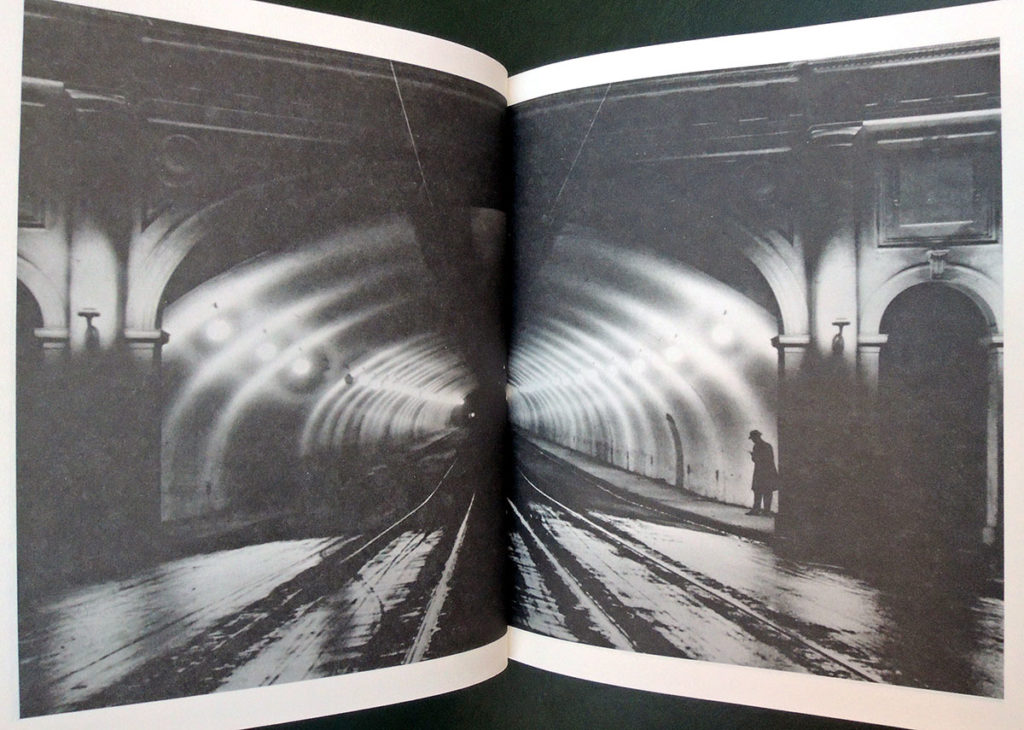

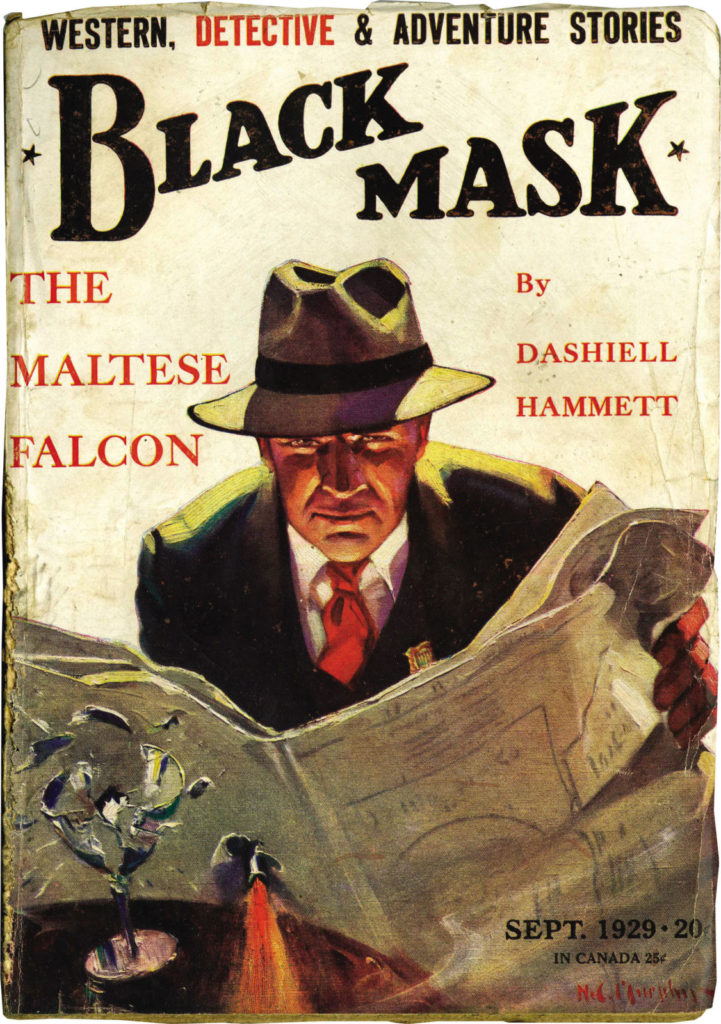

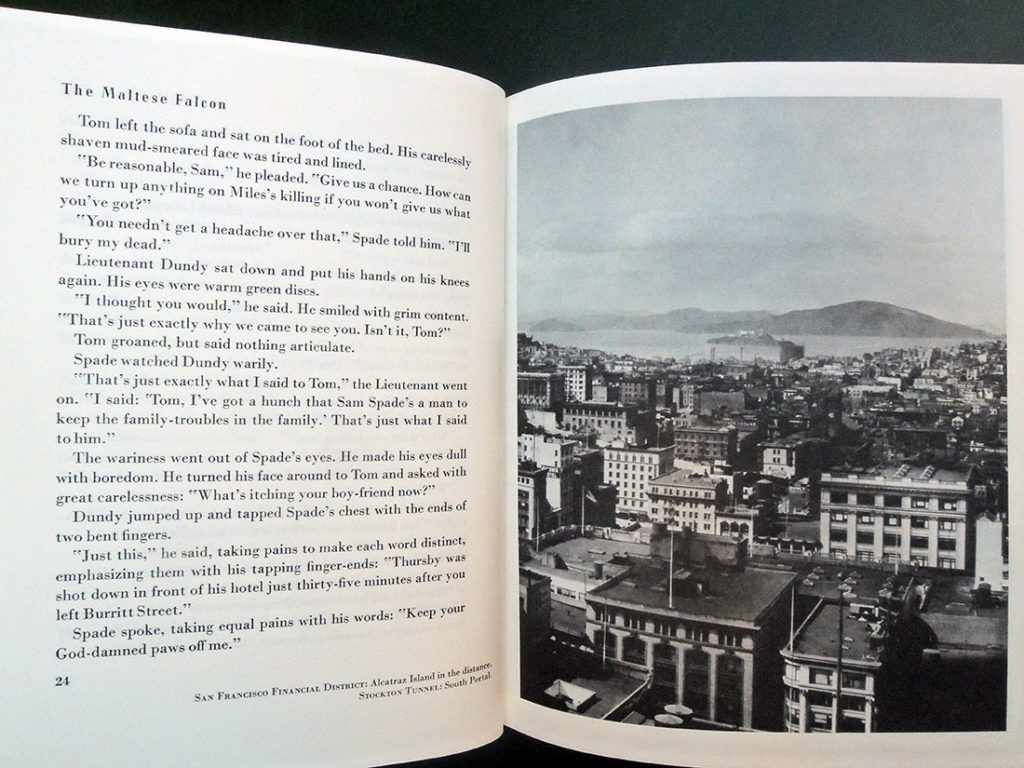

In 1983 Arion Press published a limited-edition Maltese Falcon, illustrated with 46 period photographs of sites in the novel, along with contemporary views by Edmund Shea. The photographs were found mainly in old newspaper morgues and library archives, taken in the late 1920s, of the actual streets and buildings where Sam Spade solved the mystery. The Graphic Arts Collection holds only the trade edition, published by North Point Press the following year.

See: Dashiell Hammett, “From the Memoirs of a Private Detective,” Smart Set March 1923, p. 88.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?q1=%22dashiell%20hammett%22;id=uc1.b3874453;view=image;seq=444;start=1;sz=10;page=search

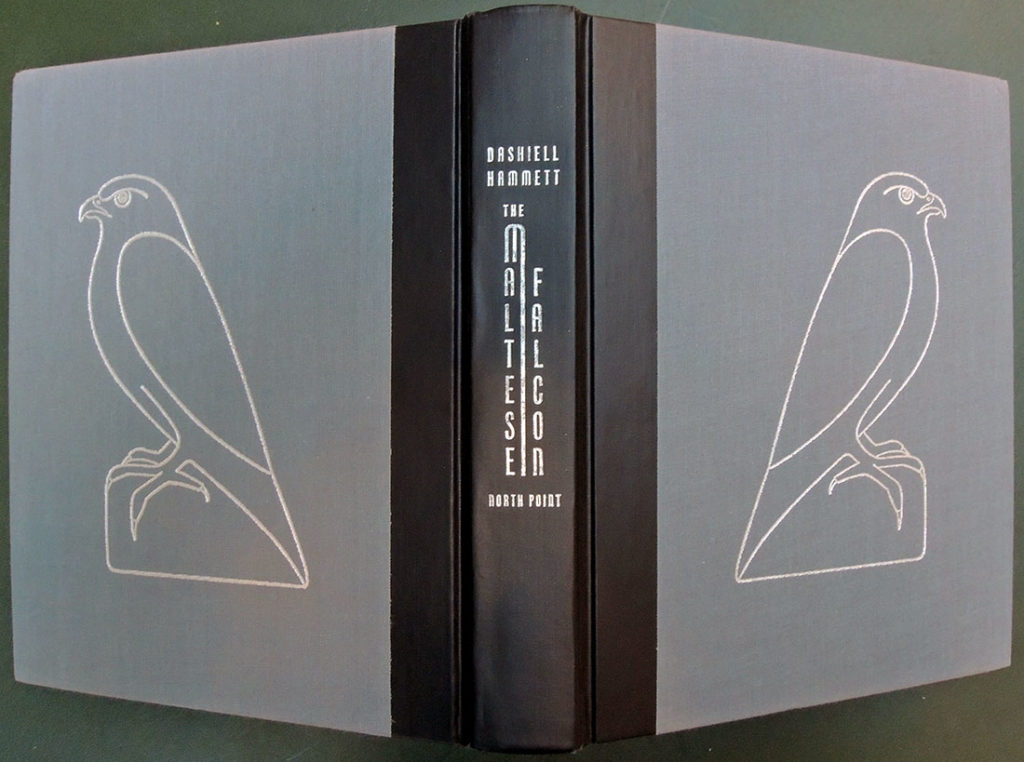

Dashiell Hammett (1894-1961), The Maltese Falcon (San Francisco: North Point Press, 1984). “This edition … is reproduced from the limited edition of 400 copies printed and published by the Arion Press, San Francisco, in 1983”–Colophon. Graphic Arts Collection PS3515.A4347 M3x 1984

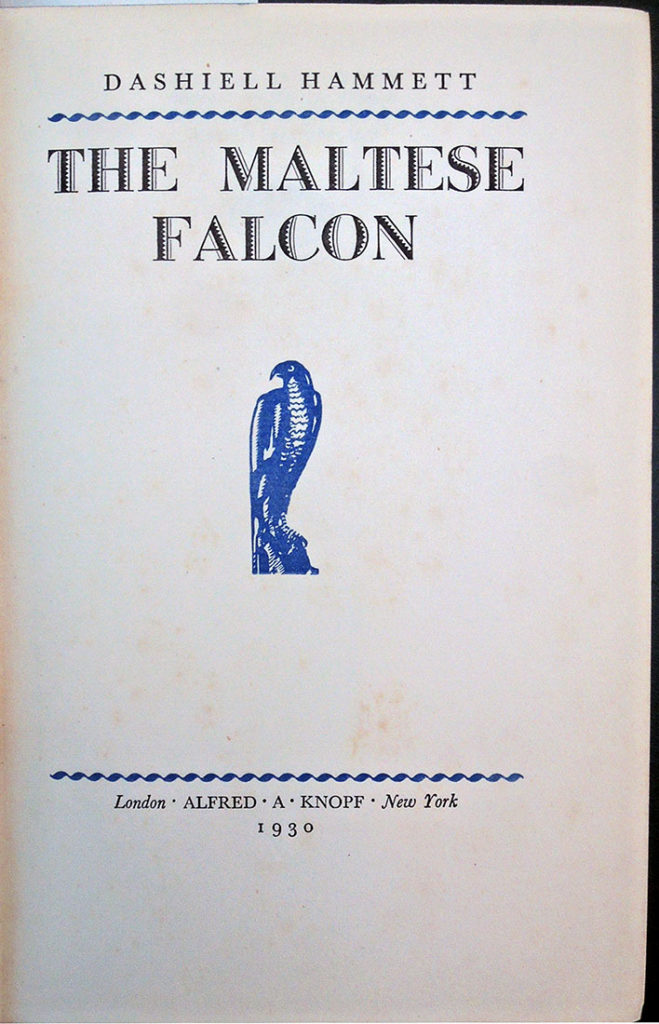

Dashiell Hammett (1894-1961), The Maltese Falcon (New York: A.A. Knopf, [c1930]). Rare Books 3769.56.359 1930