John Syme, John James Audubon, 1826, oil on canvas. White House Historical Association.

John Syme, John James Audubon, 1826, oil on canvas. White House Historical Association.

Within the first six months of John James Audubon’s arrival in Great Britain, he was immortalized with two portraits: an oil painting by John Syme and a life mask cast under the supervision of George Combe. James Fenimore Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans was taking Europe by storm and Audubon was everyone’s image of an American woodsman.

For the oil painting, he was instructed to wear his wolf-skin coat and later wrote, “if the head is not a strong likeness, perhaps the coat may be. …It is a strange-looking figure, with gun, strap, and buckles, and eyes that to me are more those of an enraged Eagle than mine.”

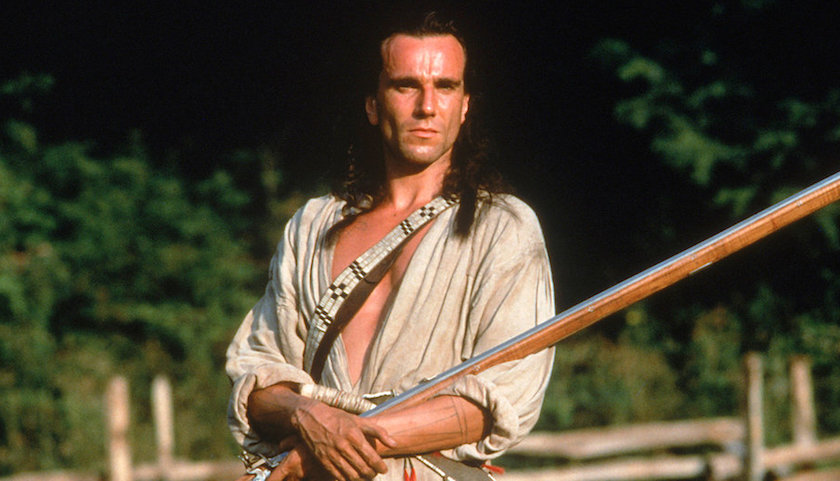

Still the portrait had lasting effect: Daniel Day Lewis in Last of the Mohicans, released September 25, 1992.

Daniel Day Lewis in Last of the Mohicans, released September 25, 1992.

N. C. Wyeth (1882-1945), Last of the Mohicans, 1919. Oil painting reproduced as the endpapers of James Fenimore Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1919).

N. C. Wyeth (1882-1945), Last of the Mohicans, 1919. Oil painting reproduced as the endpapers of James Fenimore Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1919).

https://library.princeton.edu/libraries/firestone/rbsc/aids/C0770/

https://library.princeton.edu/libraries/firestone/rbsc/aids/C0770/

November 27, 1826: …at nine was again with Mr. Lizars, who was to accompany me to Mr. Combe’s, and reaching Brower Square we entered the dwelling of Phrenology! Mr. Scot, the president of that society, Mr. D. Stewart, Mr. McNalahan, and many others were there, and also a German named Charles N. Weiss, a great musician. Mr. George Combe immediately asked this gentleman and myself if we had any objection to have our heads looked at by the president, who had not yet arrived. We both signified our willingness, and were seated side by side on a sofa. When the president entered Mr. Combe said: “I have here two gentlemen of talent; will you please tell us in what their natural powers consist?” Mr. Scot came up, bowed, looked at Mr. Weiss, felt his head carefully all over, and pronounced him possessed of musical faculty in a great degree; I then underwent the same process, and he said: “There cannot exist a moment of doubt that this gentleman is a painter, colorist, and compositor, and I would add an amiable, though quick-tempered man.”

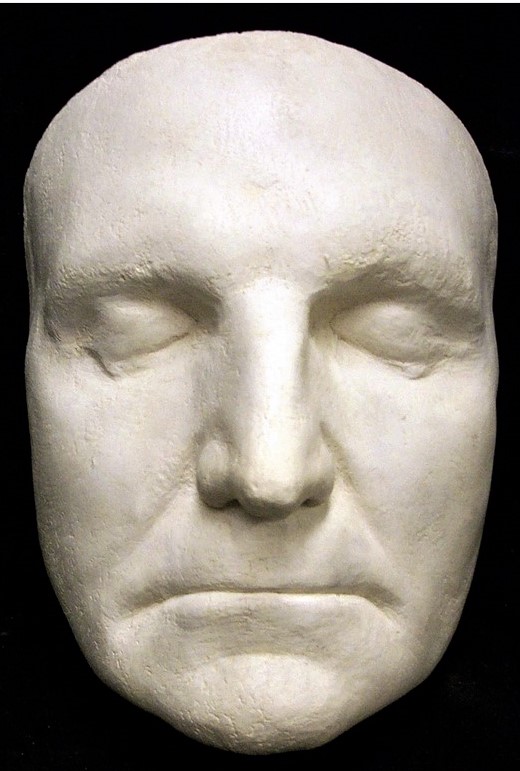

Monday, December 18: At five I dined with George Combe, the conversation chiefly phrenology. George Combe is a delightful host, and had gathered a most agreeable company. . . . Mr. Combe has been to see me, and says my poor skull is a greater exemplification of the evidences of the truth of his system than any he has seen, except those of one or two whose great names only are familiar to me; and positively I have been so tormented about the shape of my head that my brains are quite out of sorts. Nor is this all; my eyes will have to be closed for about one hour, my face and hair oiled over, and plaster of Paris poured over my nose (a greased quill in each nostril), and a bust will be made.

Wednesday, December 20: Phrenology was the order of the morning. I was at Brown Square, at the house of George Combe by nine o’clock, and breakfasted most heartily on mutton, ham, and good coffee, after which we walked upstairs to his sanctum sanctorum. A beautiful silver box containing the instruments for measuring the cranium, was now opened … and I was seated fronting the light. Dr. Combe acted as secretary and George Combe, thrusting his fingers under my hair, began searching for miraculous bumps. My skull was measured as minutely and accurately as I measure the bill or legs of a new bird, and all was duly noted by the scribe. Then with most exquisite touch each protuberance was found as numbered by phrenologists, and also put down according to the respective size. I was astounded when they both gave me the results of their labors in writing, and agreed in saying I was a strong and constant lover, an affectionate father, had great veneration for talent, would have made a brave general, that music did not equal painting in my estimation, that I was generous, quick-tempered, forgiving, and much else which I know to be true, though how they discovered these facts is quite a puzzle to me.

January 14, 1826: After receiving many callers I went to Mr. O’Neill’s to have a cast taken of my head. My coat and neckcloth were taken off, my shirt collar turned down, I was told to close my eyes; Mr. O’Neill took a large brush and oiled my whole face, the almost liquid plaster of Paris was poured over it, as I sat uprightly till the whole was covered; my nostrils only were exempt. In a few moments the plaster had acquired the needful consistency, when it was taken off by pulling it down gently. The whole operation lasted hardly five minutes; the only inconvenience felt was the weight of the material pulling downward over my sinews and flesh. On my return from the Antiquarian Society that evening, I found my face on the table, an excellent cast.–https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Audubon_and_His_Journals/The_European_Journals

James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851), Last of the Mohicans (Philadelphia: H.C. Carey & I. Lea, [February 1826]).

James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851), Last of the Mohicans (London: John Miller, [March] 1826).

James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851), Last of the Mohicans (Paris: L. Baudry, [April] 1826).