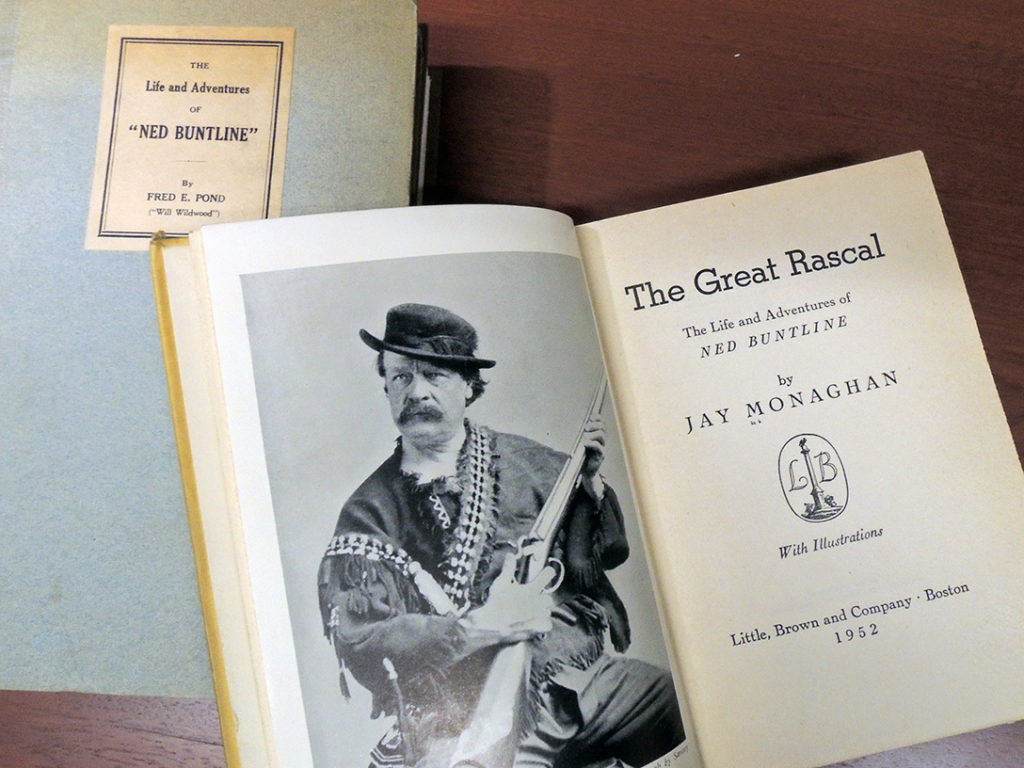

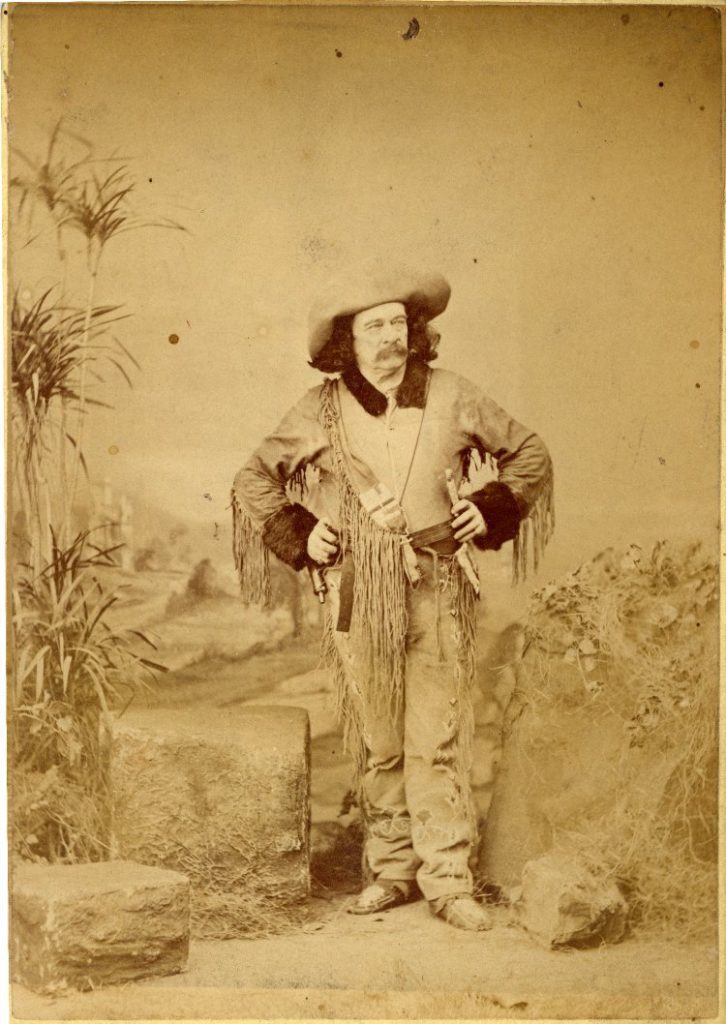

Edward Zane Carroll Judson served with the U.S. Navy from 1839 to 1842 during the Second Seminole War in Florida. While still in service, he began publishing short fiction under the pen name Ned Buntline (a buntline is one of the ropes attached to the foot of a square sail).

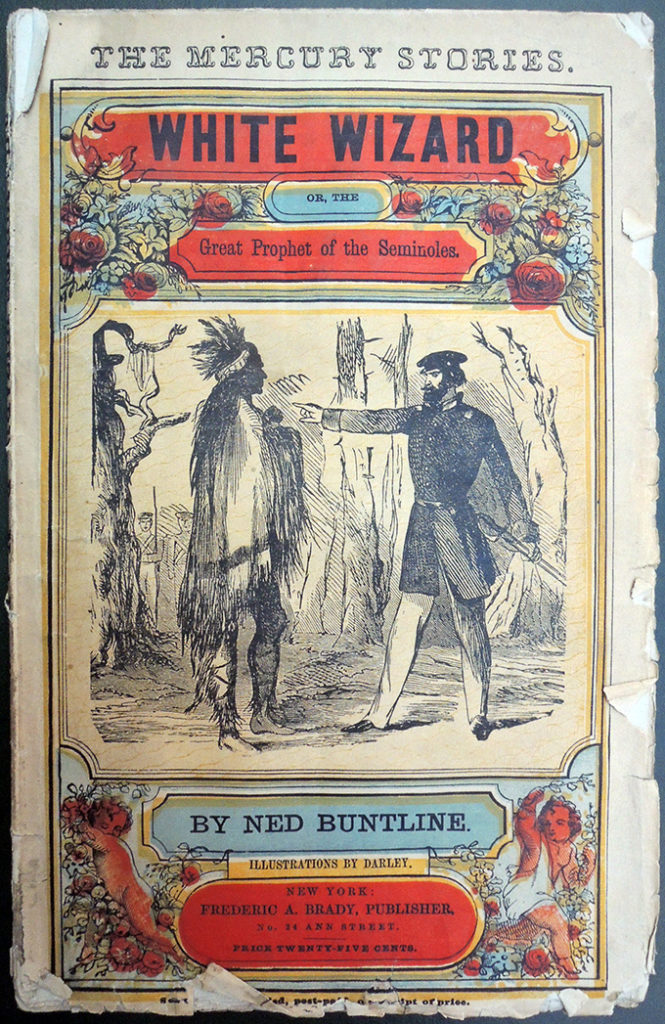

Although he is best-known for stories about the American West, many of Buntline’s early pieces relied on his personal experiences in Florida, including Matanzas, or, A Brother’s Revenge: a Tale of Florida (1848); The Red Revenger, or, The Pirate King of the Floridas. A Tale of the Gulf and its Islands (1848); and most notably, The White Wizard. Or, The Great Prophet of the Seminoles. A Tale of Strange Mystery in the South and North (Graphic Arts Collection. Oversize Hamilton 657q).

White Wizard originally appeared in the New York Mercury in 1858, later published as Beadle’s Sixpenny Tales in 1862 and American Talks in 1869.

Not only did Judson have a spectacular life but he was the best paid of all 19th-century American authors, reportedly earning ~$20,000/year in the 1860s. His stories number at least 400, but only 7 are held in the Sinclair Hamilton Collection of American Illustrated Books.

Of the many anecdotes told about Judson, perhaps the most sensational is the factual account of his hanging, from which he survived. As reported in the Washington Post, July 25, 1886, here is a section:

“Acting Mayor S.V.D. Stout and John D. Gass, who were Jail Commissioners, went to consult Louis Horn, jailer. When the mob rushed into the jail, they knocked Horn out of a rocking chair and secured the keys, when he said, “For God’s sake, don’t let all the prisoners out.” Three of the mob entered Buntline’s cell. While one caught him by a leg, another seized him by the collar. A third, placing his foot on Buntline’s neck, was about to fire, when the jailer pleaded with them not to kill him there.

Buntline was then dragged pell-mell into the street. He was then permitted to say his prayers and on finishing pulled a ring from his finger, handed it to a minister to be sent to his father at Pittsburgh, Pa. The crowd then hallooed, “Take him on,” and they did so.

They first attempted to hang him to a sign, but the rope having been too short, he was dragged to a lamp-post. When they began to pull him up, acting Mayor Stout cut the rope and the form of Buntline dropped to the earth. The utmost silence prevailed at this critical moment, when a man named Ashbrook cried out: “It’s a d—n shame to treat a human being in such a brutal manner and if John Porterfield is a gentleman, he will have the wretch turned loose!” At this Porterfield came out and said: “Take him back to jail” and Buntline was returned to his cell.

Dr. Stout said he had received severe internal injuries and that while attending him Buntline boasted that if he saw that a man was going to shoot him he could dodge the bullet. When Buntline had recovered and was about to be sent down the river, still another mob gathered at the upper wharf to lynch him; but the crowd was left standing when the boat started with no Buntline on board. The sheriff alluded the angry assemblage by taking Buntline to the lower wharf where he was put on a steamer and that was the last seen of Buntline in Nashville. “

In one obituary, possibly written by Judson himself before his actual death in 1886, it is noted that “Ned Buntline probably carried more wounds on this body than any other living American.”

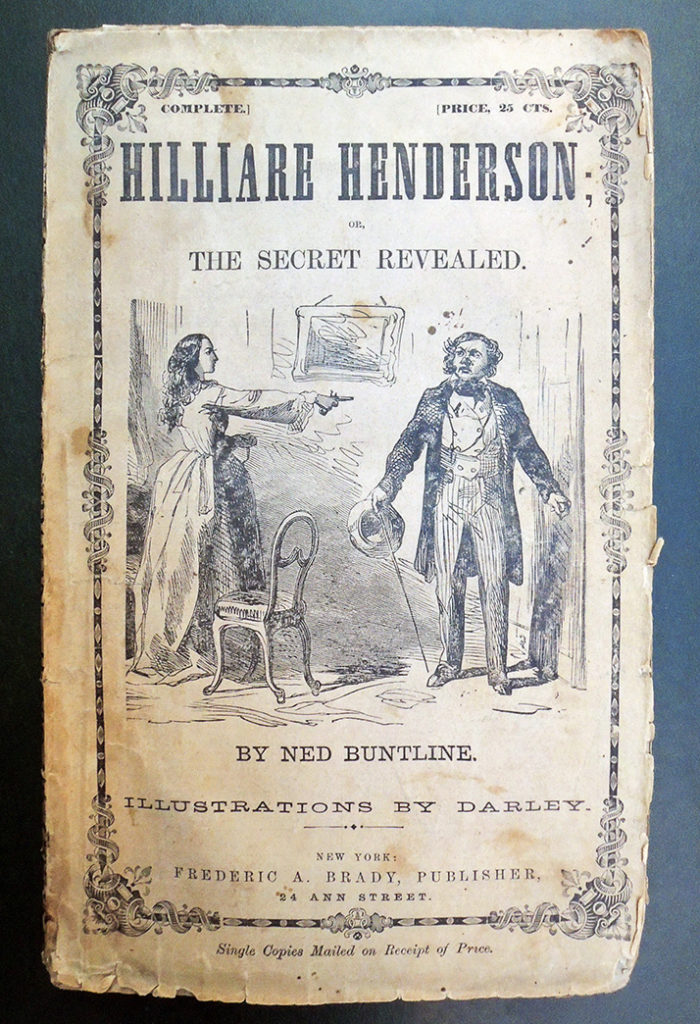

Ned Buntline (pseudonym for E.Z.C. Judson, 1822 or 1823-1886), The White Wizard. Or, The great prophet of the Seminoles. A tale of strange mystery in the South and North; illustrations by Darley. Original, chromoxylographed paper wrappers (New York: F.A. Brady [1862]). Graphic Arts Collection. Oversize Hamilton 657q

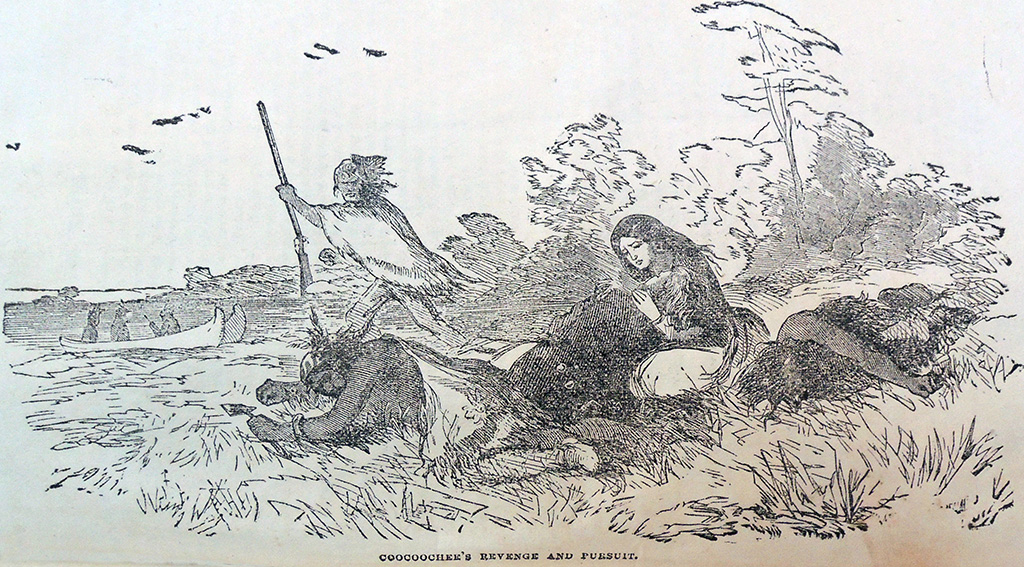

Buntline’s heroes were not always the white men.

Buntline’s heroes were not always the white men.

“…Coocoochee, a Mohawk prophetess. Though she was not a member of any of the tribes—Shawnee, Miami, and Delaware—that predominated numerically at the Glaize, Coocoochee nevertheless was treated as a revered member of the intertribal village community. Her respected position was based on her reputation as a medicine woman who conversed with numerous spirits and accurately forecast the results of raids.”

Also see Helen Hombeck Tanner, “Coocoochee: Mohawk Medicine Woman,” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 3(3) (1979): 24-25, 28. The Ohio Iroquois, known as Mmgoes, began migrating into Ohio in the 1740s and 1750s; Coocoochee’s family relocated to Ohio sometime after 1768, the year in which the first Treaty of Fort Stanwix supposedly made the Ohio River a permanent boundary and acknowledged that the country north of the River belonged solely to the Indians.

Read more: https://www.sun-sentinel.com/news/fl-xpm-1992-01-12-9201030022-story.html