Theodore Henry Adolphus Fielding (1781-1851), the elder son of Nathan Theodore Fielding, was a painter, printmaker, and teacher. He published collections of landscapes in aquatint such as: A Picturesque Tour of the English Lakes (1821), Picturesque Illustrations of the River Wye (1822), and Cumberland, Westmoreland and Lancashire Illustrated (1822).

Theodore Henry Adolphus Fielding (1781-1851), the elder son of Nathan Theodore Fielding, was a painter, printmaker, and teacher. He published collections of landscapes in aquatint such as: A Picturesque Tour of the English Lakes (1821), Picturesque Illustrations of the River Wye (1822), and Cumberland, Westmoreland and Lancashire Illustrated (1822).

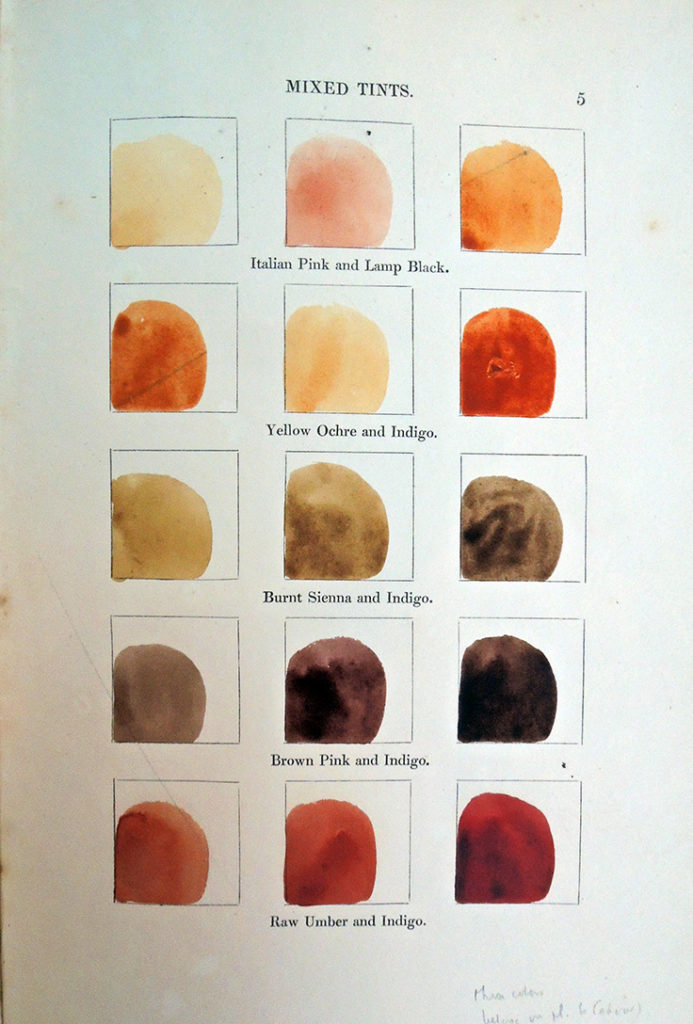

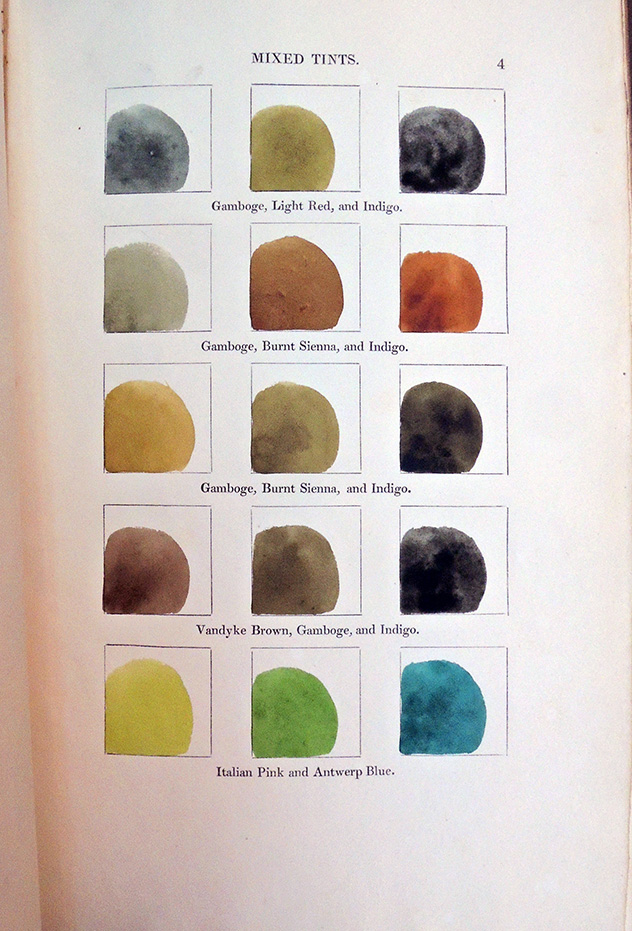

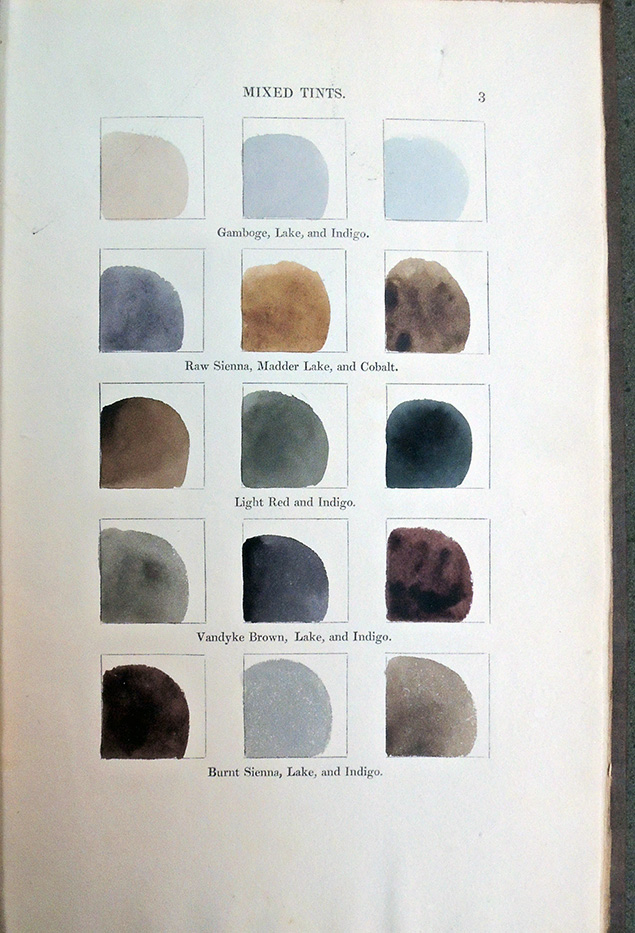

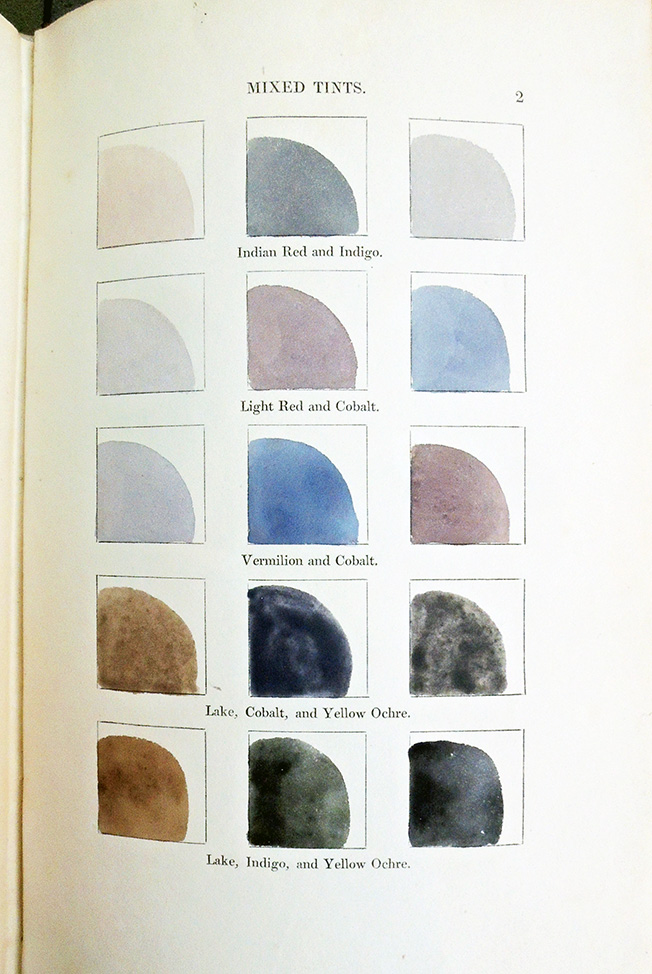

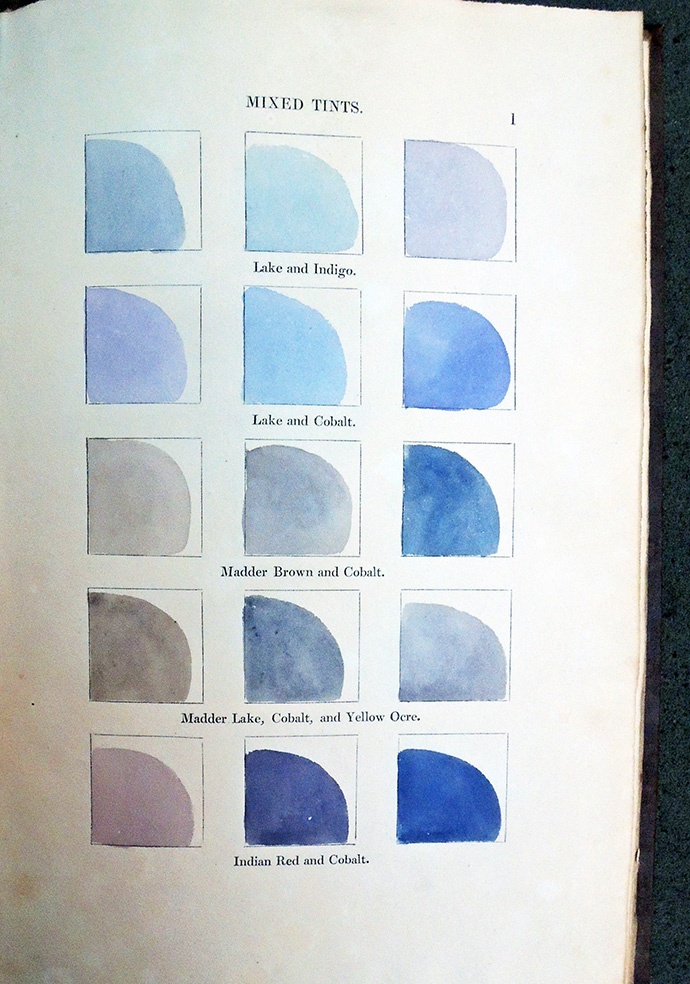

Beginning in 1830, while still a painting instructor to the “senior classes at the Honourable East-India Company’s military Seminary” at Addiscombe, Surrey, Fielding began publishing manuals on painting, perspective, and art theory. In particular, his expertise on mixing color pigments was beautifully documented in physical sample of brightly printed color, as seen here.

The books were so popular and went through so many editions that it is often difficult to put dates to them. For instance, there were “enlarged, 2nd editions” of his On the Theory of Painting in both 1835 and 1836. Thanks to the generous donation of Dickson Q. Brown, Princeton Class of 1895, the Graphic Arts Collection has two now rare examples:

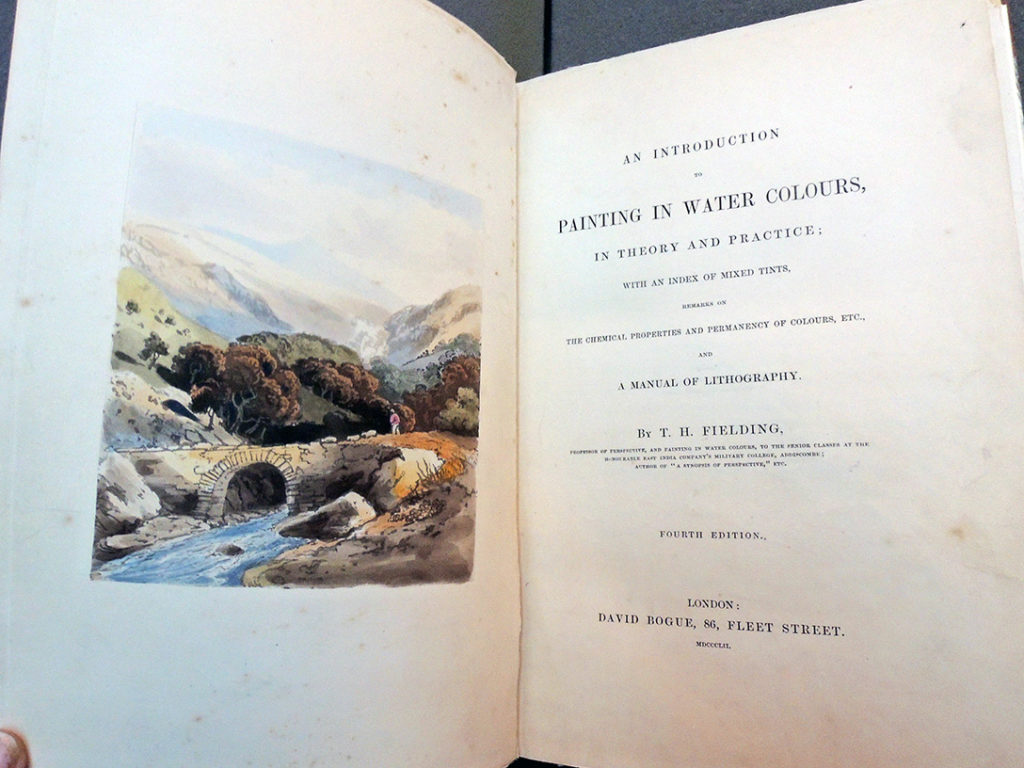

Theodore Henry Fielding (1781-1851), An introduction to painting in water colors: in theory and practice: with an index of mixed tints, remarks on the chemical properties and permanency of colours, etc., and a manual of lithography (London : D. Bogue, 1852). Graphic Arts Collection Rowlandson 671.2

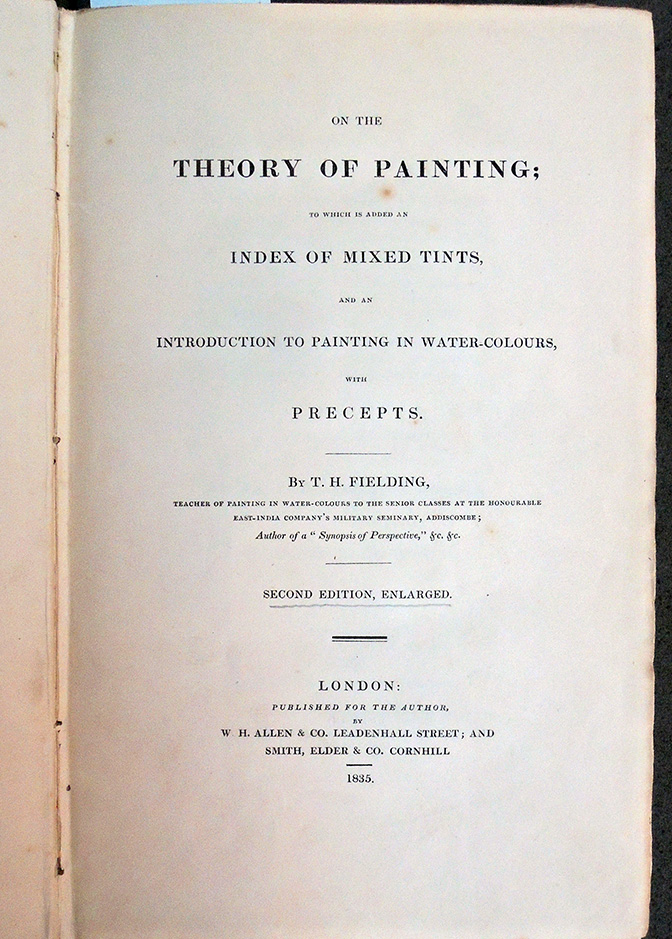

Theodore Henry Fielding (1781-1851), On the theory of painting; to which is added and index of mixed tints, and an introduction to painting in water-colours, with precepts (London, W.H. Allen, 1836). Graphic Arts Collection Rowlandson 671

Fielding included this quote from Sir Joshua Reynolds on the title page of many of his volumes: “The rules of art are not the fetters of genius, they are fetters only to men of no genius.”

Fielding included this quote from Sir Joshua Reynolds on the title page of many of his volumes: “The rules of art are not the fetters of genius, they are fetters only to men of no genius.”

Of the nature of colours, nearly all we know is, that they exist in various tinted rays, which combined make pure or colourless light. Could the artist be made acquainted with their physical or first cause, and how objects receive their colours, he might obtain some advantages, for they are not so splendidly and lavishly displayed throughout the works of Nature without some great meaning, otherwise their existence would seem only for our amusement instead of instruction.