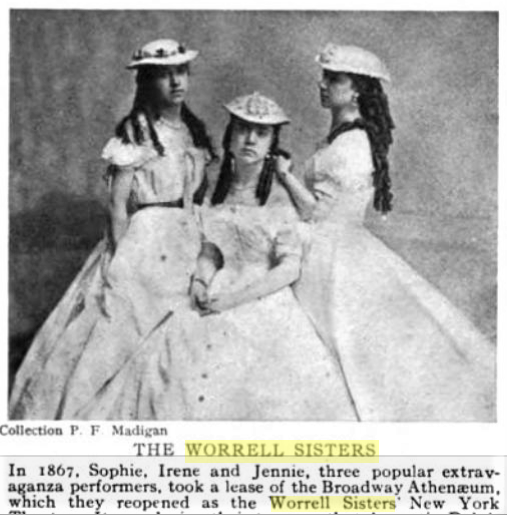

Jennie, Sophie, and Irene Worrell. University of Nevada, Reno, Library. UNRS-P1348

Jennie, Sophie, and Irene Worrell. University of Nevada, Reno, Library. UNRS-P1348

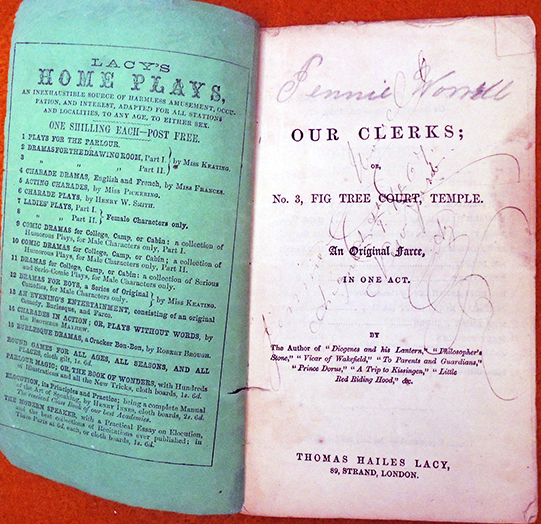

Tom Taylor (1817-1880), Our Clerks, or, No. 3, Fig Tree Court, Temple: an original farce, in one act … (London (89 Strand): T.H. Lacy, [186-?]). Theatre collection TC23, 156a. Rehearsal script owned by Jennie Worrell (1850-1899), who played the character of Edward Sharpus, dated [August? 9th?] 1867 New York.

Tom Taylor (1817-1880), Our Clerks, or, No. 3, Fig Tree Court, Temple: an original farce, in one act … (London (89 Strand): T.H. Lacy, [186-?]). Theatre collection TC23, 156a. Rehearsal script owned by Jennie Worrell (1850-1899), who played the character of Edward Sharpus, dated [August? 9th?] 1867 New York.

Buried in box 156a of the American playbill collection at Princeton is the script for Tom Taylor’s Our Clerks, or, No. 3, Fig Tree Court, Temple used by Jennie Worrell (1850-1899) during a 1867 production, in which she played the role of Edward Sharpus. Given this was a farce performed at the height of Victorian burlesque theater—think Saturday Night Live with more music—a female actress playing a male character is not surprising. The revelation comes with the personal story of this celebrated actress, director, producer, who died penniless, sleeping in the weeds on the outskirts of Coney Island.

Born in Cincinnati, the youngest of three sister, Jennie began performing at the age of eight. Her father was William Worrell (1823-1897), a successful circus clown, who developed a stage act with his daughters, first performed in San Francisco and then, toured throughout the United States.

Born in Cincinnati, the youngest of three sister, Jennie began performing at the age of eight. Her father was William Worrell (1823-1897), a successful circus clown, who developed a stage act with his daughters, first performed in San Francisco and then, toured throughout the United States.

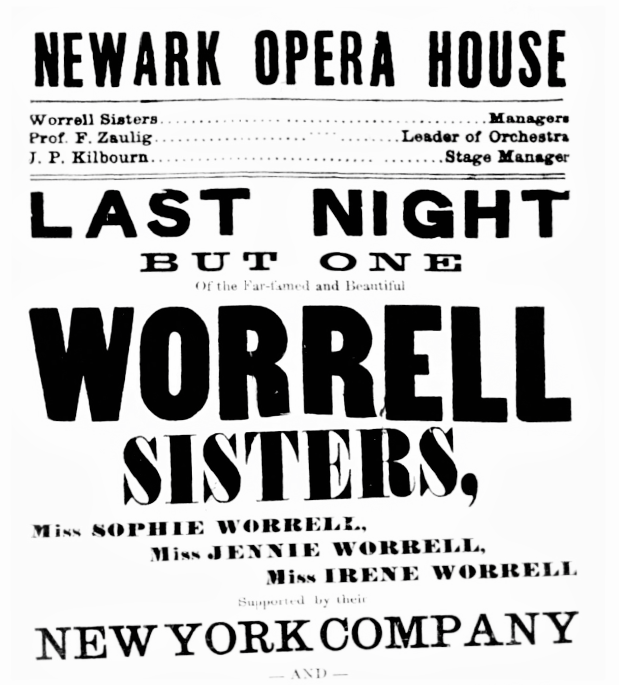

They brought the act to New York City in 1866 when Jennie was 16 years old (recording her age as 14), Irene was around 18, and Sophie approximately 20. Given their notoriety and extensive background in the theater, the sisters leased the Church of the Messiah building at Broadway and Waverly Place, recently converted to a legitimate theater and renamed it the Worrell Sister’s New York Theater. Together the women managed the space and produced the plays, while also directing and acting in many of the productions.

It was at the Worrell’s theater that Augustin Daly (1838-1899) first presented Under the Gaslight, which included the now famous scene where a man is tied to the railroad tracks, only to be saved by the heroine. The play’s success led to a return engagement with the Worrell sisters playing the major roles and featuring Jennie, who stole the show when she grabbed an ax and saved the young man from an oncoming train.

Later versions switch the gender roles.

Performances at the Worrell Sister’s theater sold-out as their admirers multiplied. One review in the New-York Tribune, May 18, 1867, said:

“At the New-York Theater the Three Graces of Burlesque, Sophie, Jennie, and Irene Worrell, are attracting larger and still larger audiences as the season wears on. On Thursday evening the attendance was particularly good, and the performance particularly vivacious and pleasant. …These lively and talented young ladies—who originally made their appearance in this city last season … have grown steadily in favor with that portion of the public which craves dramatic merriment, until at last they have secured what, in religious parlance, may be termed a considerable following. They are pretty, and lively, and innocently mischievous; and they sing, and dance, and pleasantly prattle through the lightest of plays….”

Later that season, Jennie played the shrewdly hilarious role of Edward Sharpus in Tom Taylor’s Our Clerks, in which two barristers share an office and the love of the same woman, while always being outwitted by their clerks. Writing under a pseudonym, Tayler (1817-1880) penned many of the most successful plays of the period, including Our American Cousin (attended by Abraham Lincoln), and went on to edit Punch magazine.

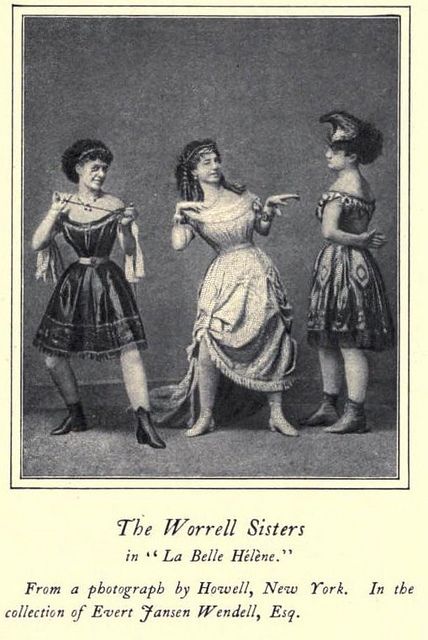

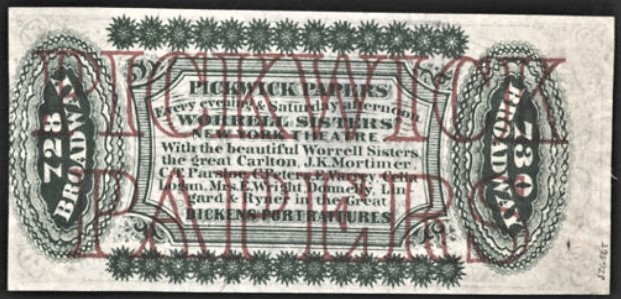

Highlights of the 1868 season included The Grand Duchess of Gérolstein with Sophie as the Grand Duchess, Irene as Wanda and Jennie as Prince Paul, followed by a stage version of Charles Dickens’ Pickwick Papers, adapted by Augustin Daly. To advertise the production, the sisters circulated dollar bills that looked real until you read the fine print, announcing their play.

After a number of years, the sister gave up management of the theater and chiefly toured the most successful of their productions. One reviewer noted: “The beautiful and accomplished Worrell sisters in the early seventies created a veritable furor throughout the country. The “Johnnies” went fairly wild over their grace, their beauty and their symmetry of form. The younger of the three pretty burlesquers was Jennie, who had hazel eyes and rich brown hair. Jennie was the especial favorite of the trio.” Another commented, “The beautiful voluptuous Jennie Worrell supped late, drank champagne, owned fast horses, wore diamonds, squandered money to right and left [until] the public grew weary of burlesque art and another group of performers began to attract attention.”

Each of the sisters married. Jennie’s first husband was Mike Murray, an infamous gambling proprietor and friend to Boss Tweed, with whom she had a daughter in 1872 named Jennie (also called Laura). The 1880 census lists the entire Worrell family living on Union Street in Brooklyn, husbands included, although Jennie is listed as a border (probably staying there in between fights with her husband). Eventually Mike and Jennie divorced, at which time she married John Alexander Chatfield (also listed as Hatfield) and moved to Surrey, England, until his death.

When she returned, Mike turned their daughter against her mother, disappearing with the girl and leaving Jennie heart-broken (See “Daughter… Forsake Her Mother,” New York Tribune March 10, 1888). This was the beginning of her down-turn, intensified by her lack of funds as these and other husbands or lovers left her with diminishing finances.

By the 1890s, Jennie had lost her home and her family disowned her, due to her drinking and disreputable behavior. The New York Times reported one arrest and conviction in 1896, during which she told one reporter:

“I thought how joyfully I would welcome death for myself. Then I determined to end my life by poison. I was not strong enough to carry out my intention, however I stopped at a druggist’s on my way to the boat and had a drink of brandy. I had not been accustomed to drinking and in my weak state it immediately affected my head. I welcomed anything that would make me forget that would bring me release form my dreadful thoughts. I took two more drinks. Then I came to New York. This was Sunday night. I had no home to which to go. All night I wandered around the streets. When daylight was approaching I entered the police station on west forty seventh street and asked for lodging and care. Perhaps I was boisterous I don’t know.”

The Actors Fund of America was notified of her plight but took no action. When the same story was reported in her hometown Cincinnati newspaper, Jennie is described as spiteful and vindictive, grinning at the magistrate when he asked her name. “Jennie Worrell!” she said, “Hard to believe, isn’t it Judge?”

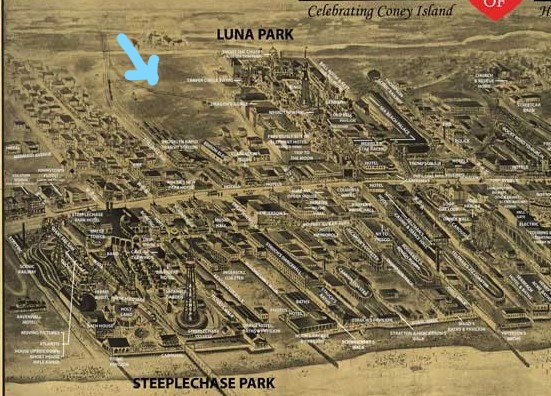

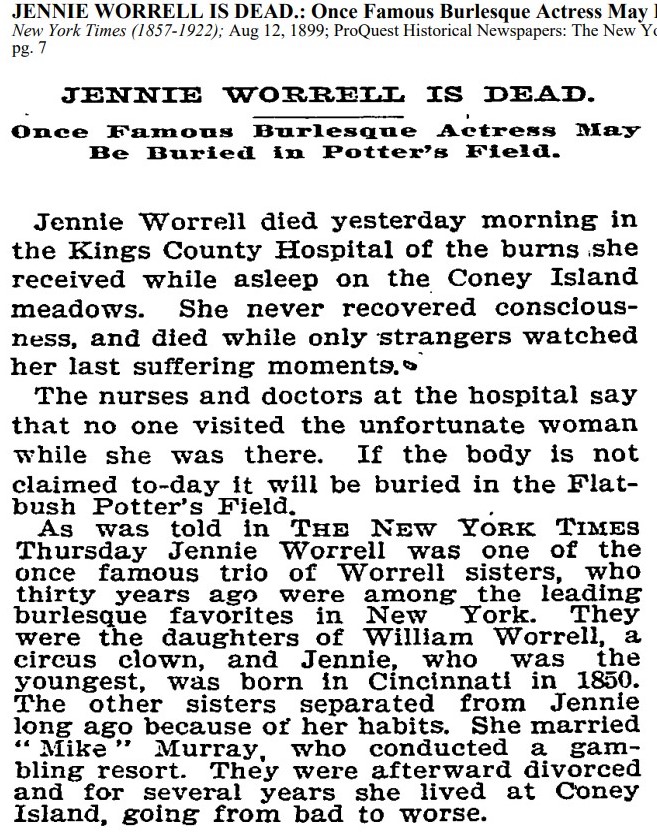

On August 10, 1899, Jennie was wandering in the marshes outside Coney Island, in the area where Luna Park would be built a few years later. Exhausted, she laid down to sleep. It is presumed that she lit a cigarette and threw the still-lit match into the weeds, which caught fire. Although several heard her screaming, she wasn’t found until much later when the fire department was called and extinguished the blaze. The Cincinnati Enquirer reported, “Jennie Worrell, the most famous stage beauty of a quarter of a century ago, is to-day battling for life in the King’s County Hospital. The face and form, which were once the admiration of thousands, are misshapen and blistered. She was all but burned to death in a fire, which swept the flats at the west section of Coney Island. The doctors say she cannot live.” Jennie Worrell died in the hospital the following day, never having recovered consciousness.