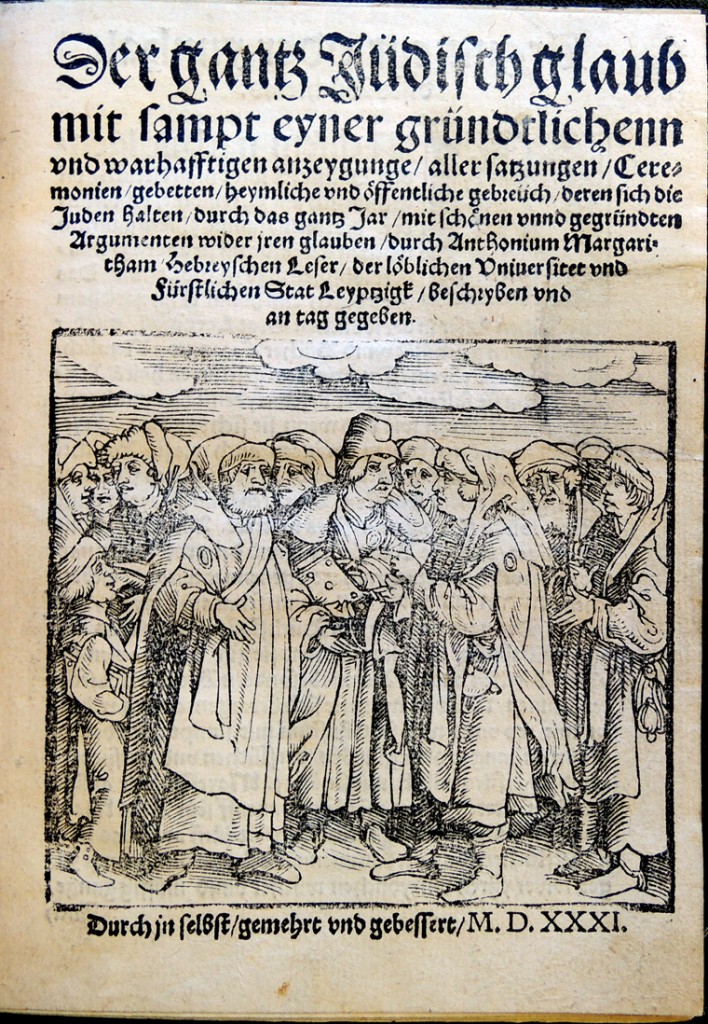

Anton Margarita (born around 1490) was the son of a rabbi who converted first to Catholicism and then became a Protestant. He published Der gantz Jüdisch glaub [The Entire Jewish Faith] in 1530, which had a second edition the same year and a third in 1531. Princeton recently acquired a copy of the rare 1531 edition.

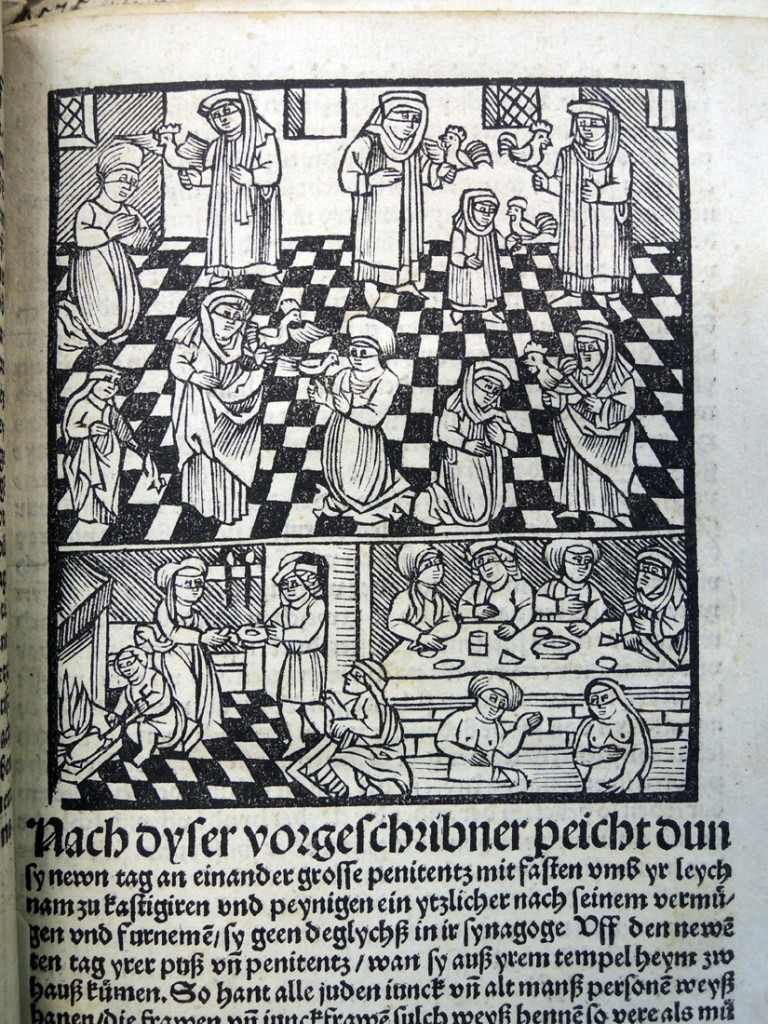

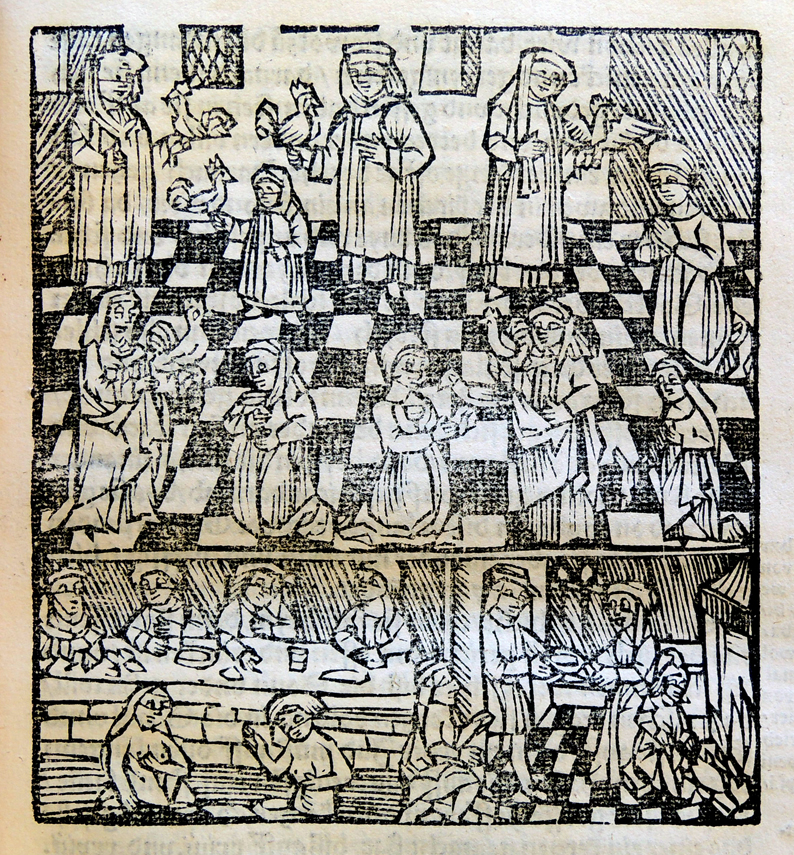

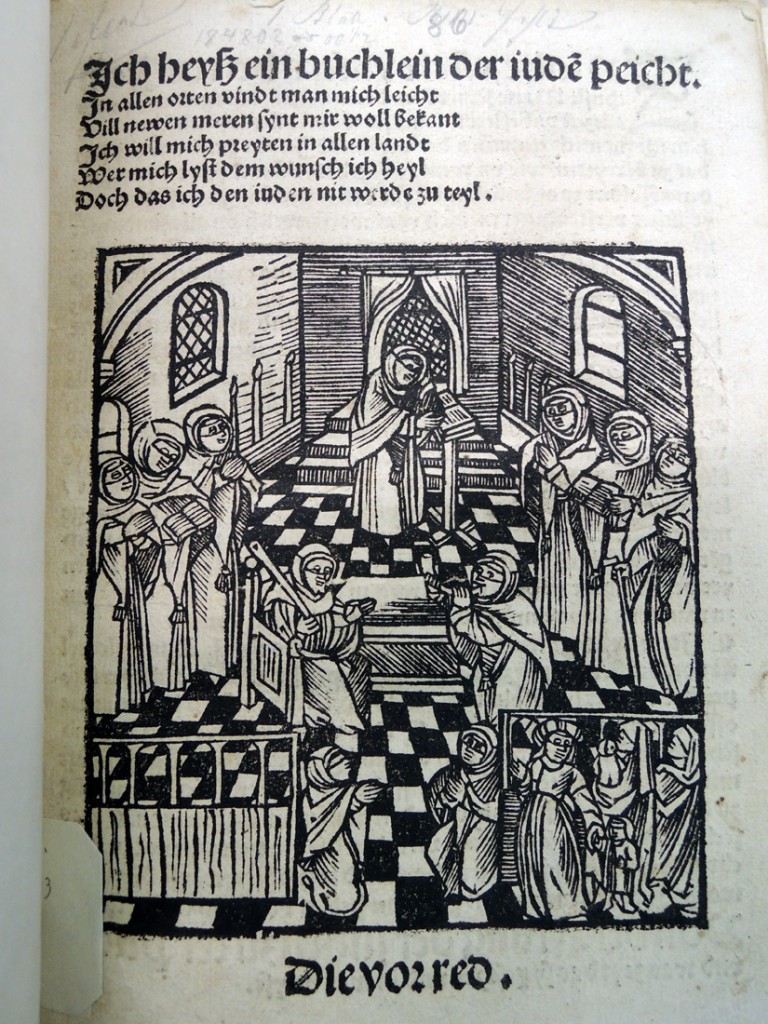

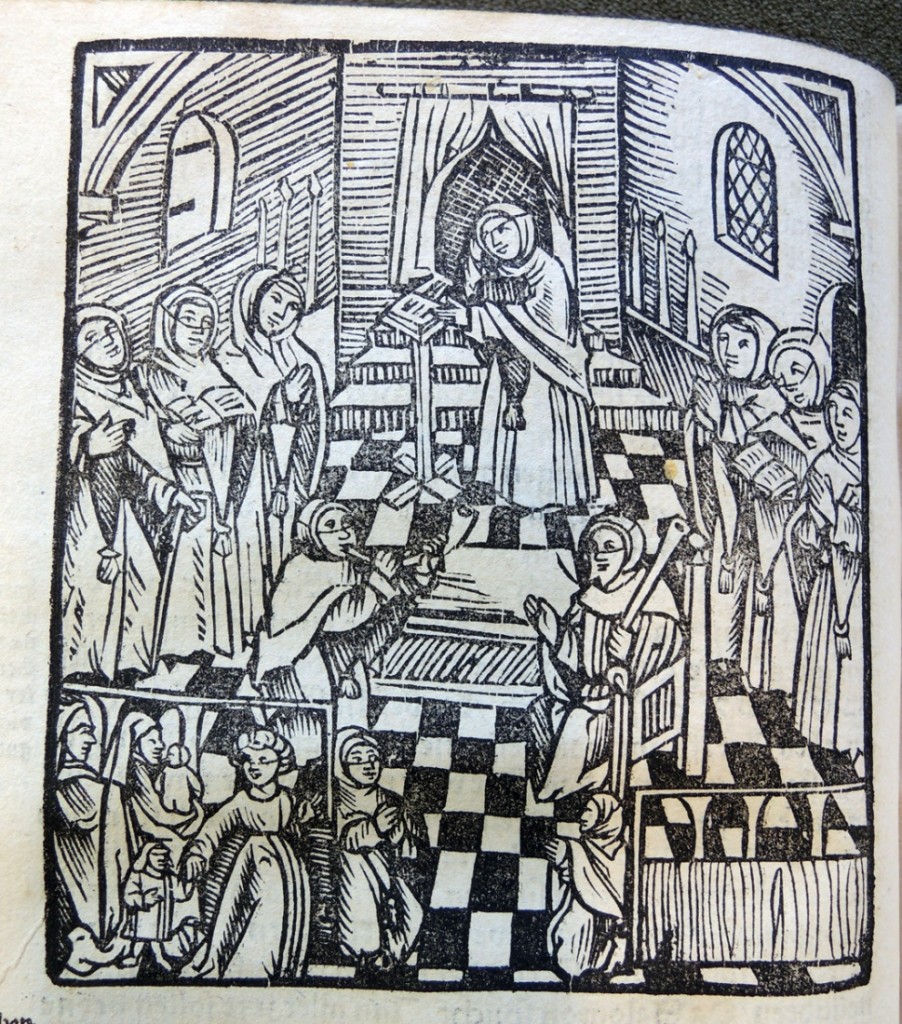

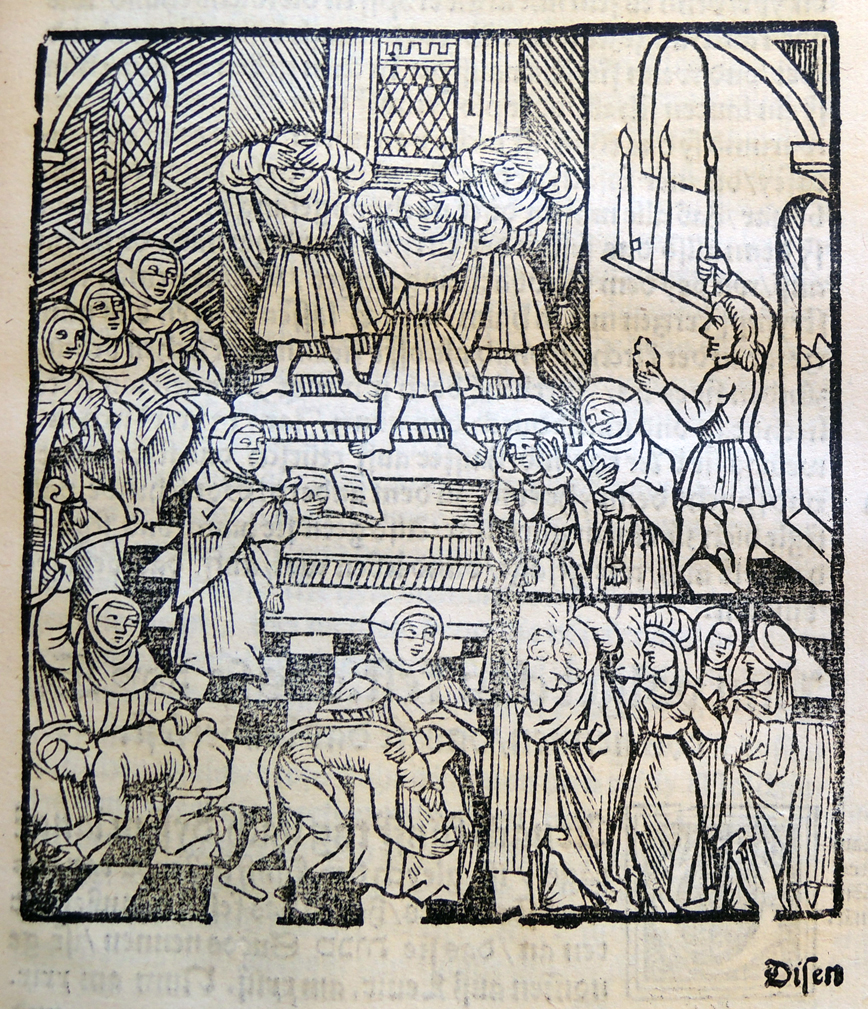

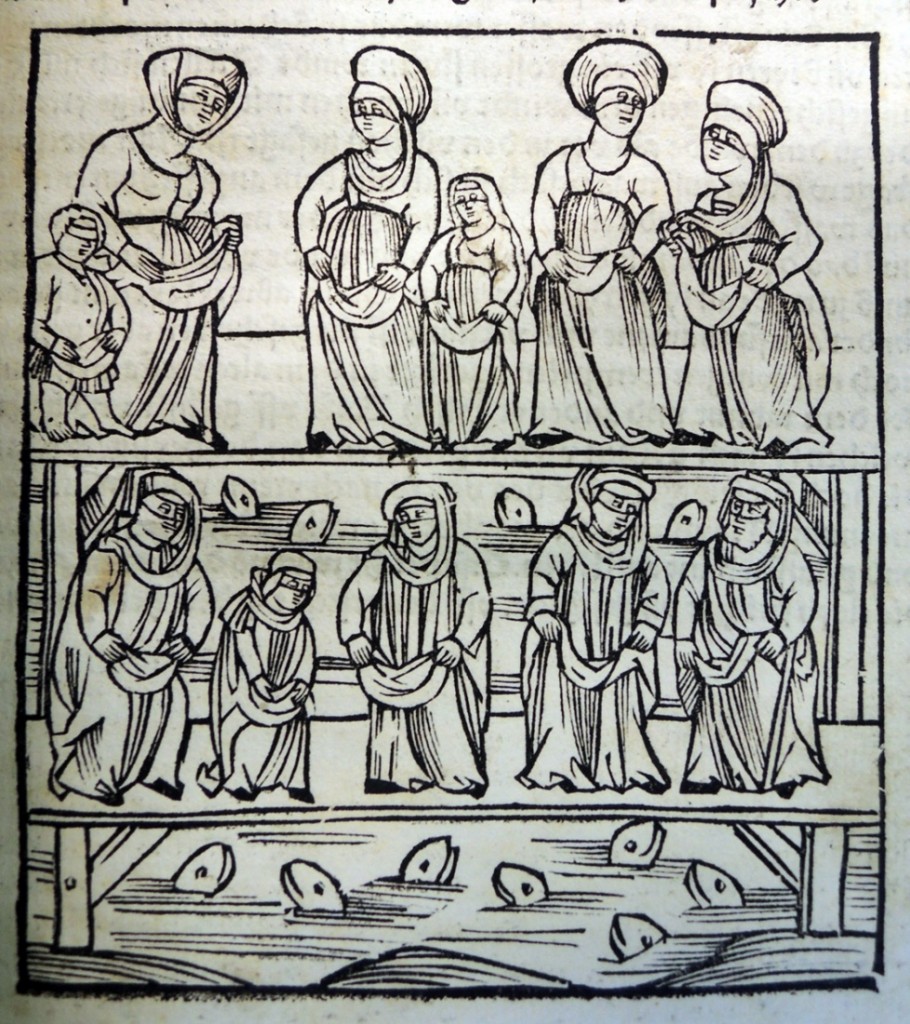

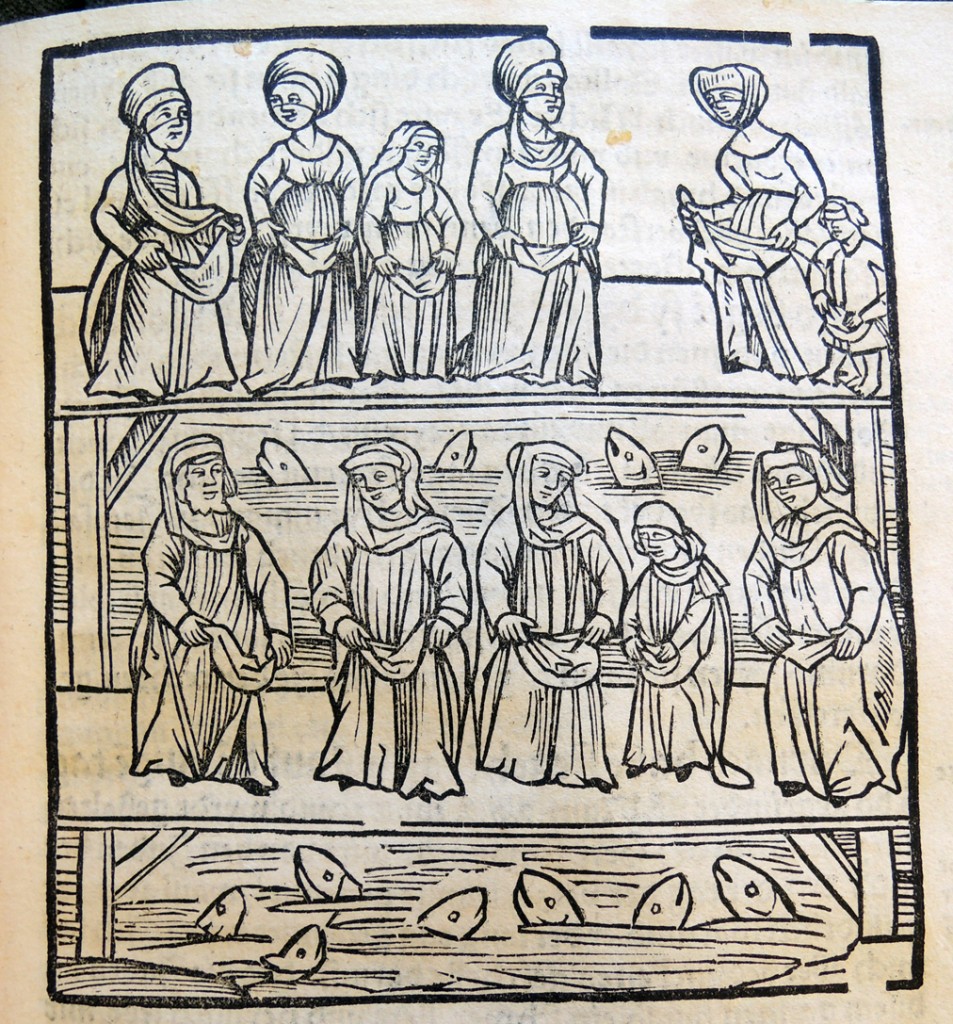

Margarita illustrated his text, a sort of encyclopedia of Judaism, with the same series of woodcuts used by Johann Pfefferkorn (1469-1523) who similarly renounced Judaism and wrote about it in 1508. The cuts were designed for Pfefferkorn’s Ich heyss ein buchlein der iude[n] beicht, and twenty-two years later, possibly traced (laterally reversed) and re-carved. The cuts have too many small discrepancies to be printed from the same woodblock. The title page cut for Margarita’s book was designed separately and has been attributed to the German painter Jörg Breu the Elder (ca. 1475–1537).

Ich heyss ein buchlein (1508) on the left and Der gantz Judisch glaub (1531) right

Ich heyss ein buchlein (1508) on the left and Der gantz Judisch glaub (1531) right

Margarita’s book and his misinterpretation of the Jewish traditions led to enormous controversy. The author was imprisoned and later, banished from Augsburg. For better or worse, his book was reprinted many times and was widely read.

R. Po-chia Hsia comments about it in The Myth of Ritual Murder: Jews and Magic in Reformation Germany: “The intention of composing The Entire Jewish Faith, as Margaritha informed his readers, was to depict the ceremonies, prayers, and customs of the Jews based on their own books; he wanted to “expose” the “false beliefs” of the Jews and to show how they curse the Holy Roman Empire and Christians in their liturgy.”

“Margaritha’s ultimate goal was the conversion of his fellow brethren to the new faith, which he himself had accepted. The main body of the book consists of a German translation of the liturgy and prayers used by the Jewish communities in the Holy Roman Empire, spiced with extensive commentaries on the history and meanings of Jewish feasts, ceremonies, and customs, lengthy diatribes against usury and rabbinic authority, and a cornucopia of anecdotes and descriptions of contemporary Jewish communal life.”

Ich heyss ein buchlein (1508) on the left and Der gantz Judisch glaub (1531) right

“For the first time, Christians could read in German the liturgy and prayers of Jews; find out in detail the observance of the Sabbath, the Passover, Yom Kippur, the performance of circumcision, [and so on]… The Entire Jewish Faith exerted a profound influence on the evaluation of Jews by the new Lutheran church: Luther read it, praised it, recommended it, and was confirmed in his belief that both Jews and Catholics were superstitious and relied foolishly on good works for their salvation.”–R. Po-chia Hsia, The Myth of Ritual Murder: Jews and Magic in Reformation Germany (Firestone BM585.2 .H74 1988

Johann Pfefferkorn (1469-1523), Ich heyss ein buchlein der iude[n] peicht (Getruckt zu Nurnberg [Nuremberg]: Durch herr Hansen Weissenburger, Im funffhunderte[n] vn[d] achte[n] iar [1508]). Rare Books (Ex) 1580.152 nos. 86-99. On the left

Anton Margarita, Der gantz Jüdisch glaub [The Entire Jewish Faith] [Augsburg: Heynrich Steyner], 1531. Six woodcuts. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2013- in process. On the right