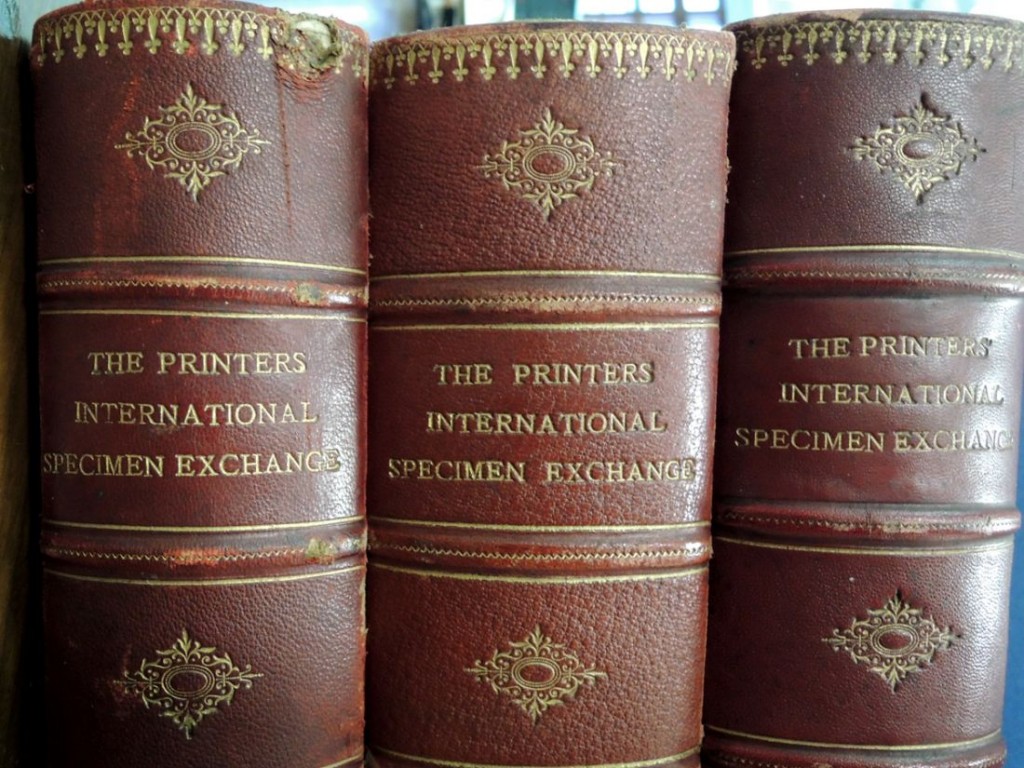

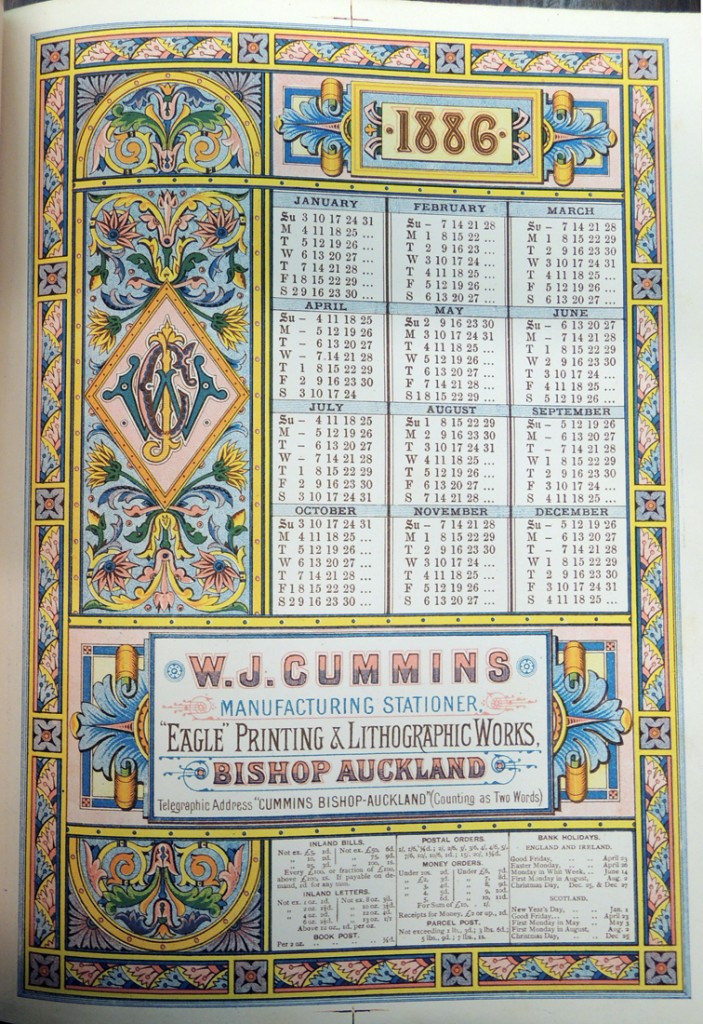

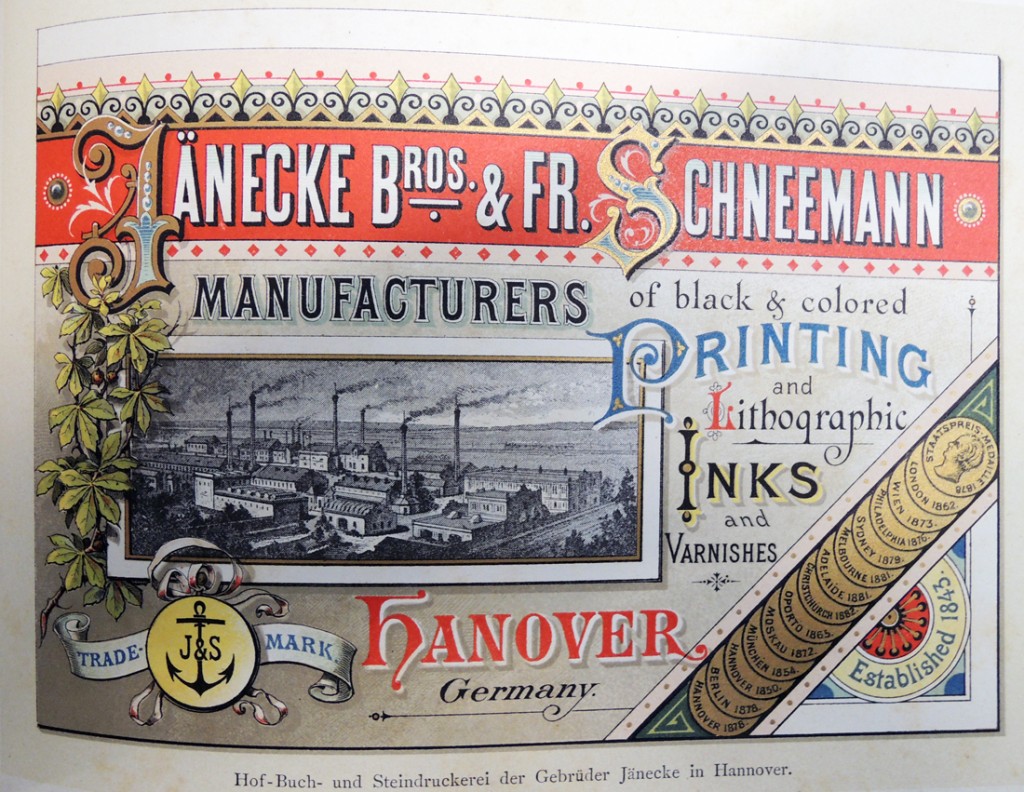

The Printers’ International Specimen Exchange (London: Office of the Paper and printing trades journal, 1880-1898). Graphic Arts Collection, vol. 5 (1884), 7 (1886), and 8 (1887).

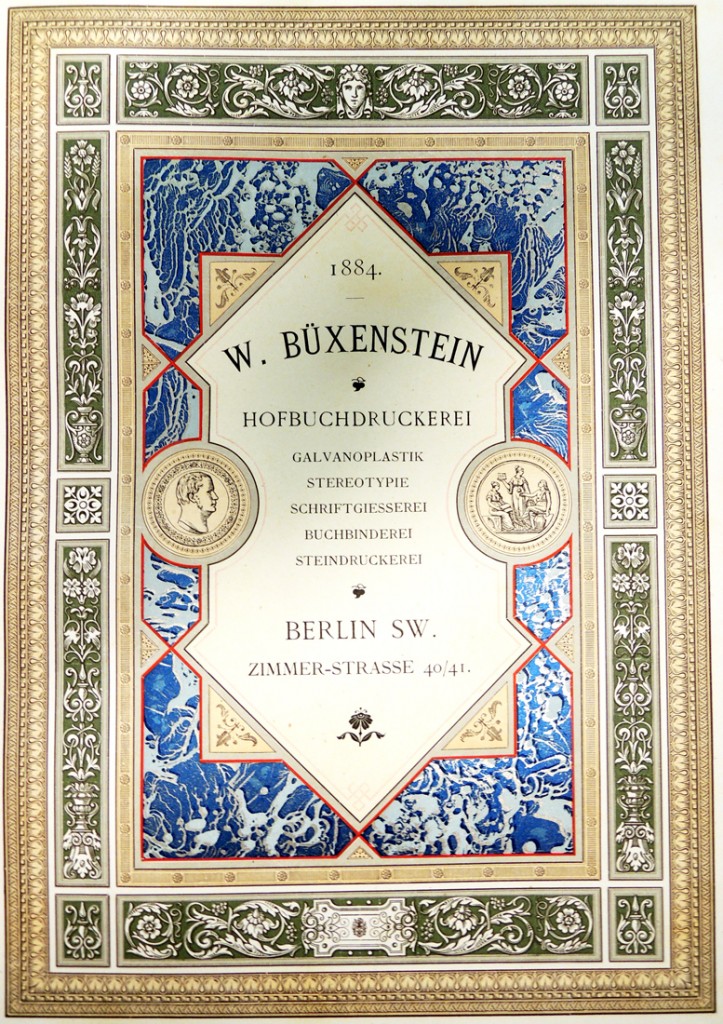

Thanks to Matthew Young’s recent study, we now know that the Printers’ International Specimen Exchange was founded in 1880, first and foremost as a means to encourage British printers to improve their technical and artistic skills, seen as lagging behind their American and European counterparts. It came to be a far more international than its originators imagined, encompassing 16 volumes with the work of more than 1,000 printing establishments from 28 different countries.

The Graphic Arts Collection recently acquired three of these rare annuals, published in editions of only a few hundred copies and meant expressly for members of the exchange. The volumes document some of the most elaborate printing from the end of the nineteenth century.

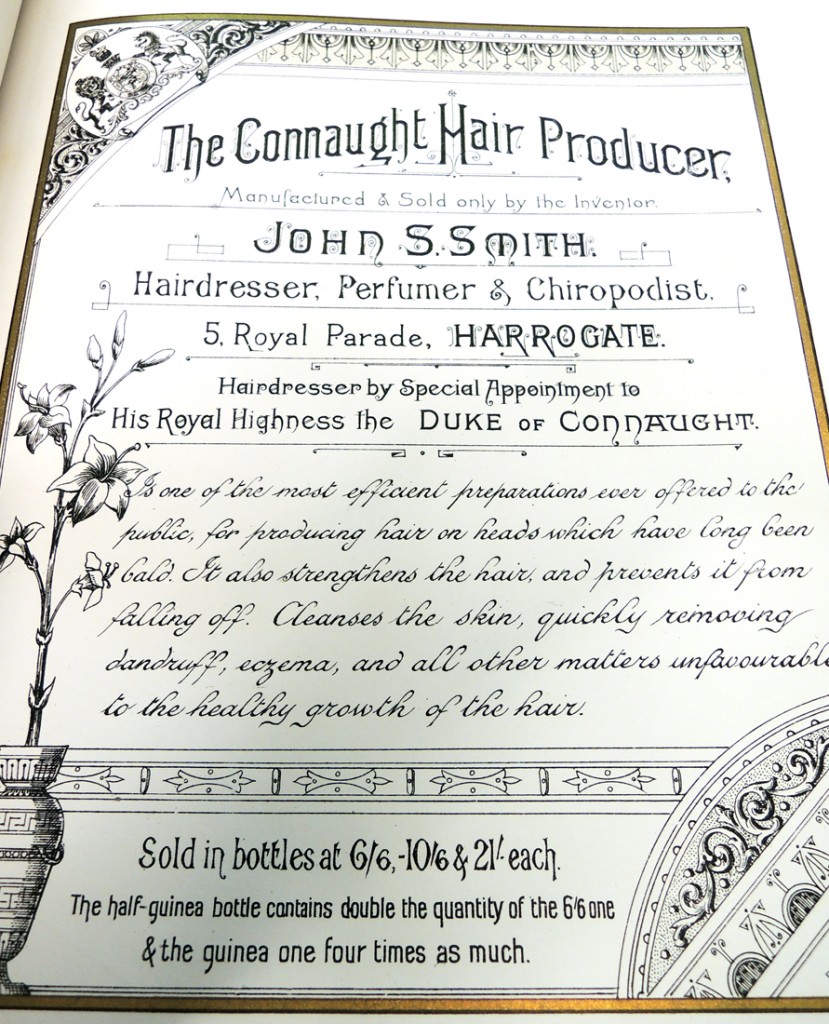

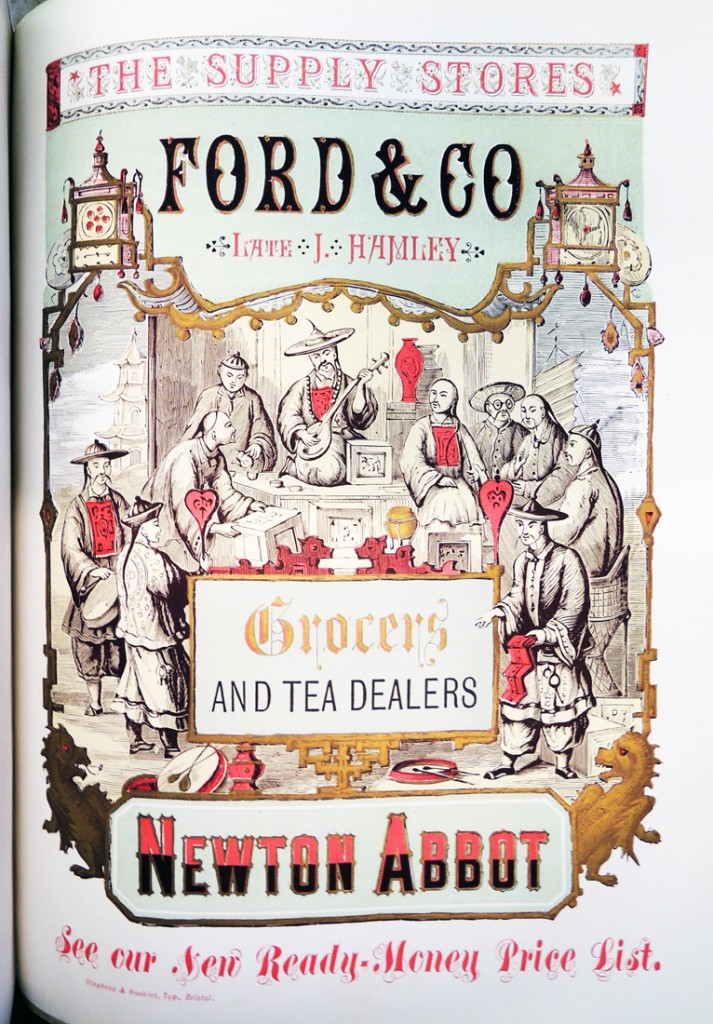

The over-the-top decoration of these printers had both supporters and detractors. The first editor of the exchange, Andrew Tuer (1838-1900) published a letter of support from John Ruskin (1819-1900) in the first volume, “It seems to me…that a lovely field of design is open in the treatment of decorative type…not in the mere big initials in which one cannot find the letters but in the delicate and variably fantastic ornamentation of capitals and filling of blank spaces or musically-divided periods of sentences and breadths of margin.”

Theodore Low DeVinne (1828-1914), on the other hand, spoke sarcastically about these printers, noting, “what advances have we made in rule-twisting! What unknown possibilities in typography have been developed by our new race of compositors! …How it does delight us to employ a typographical gymnast who tortures brass rules and spends hours and days in experiments with borders, fancy job types, tint grounds, and flourishes!” (Historic Printing Types, a Lecture Read before the Grolier Club, Ex 0220.296.2).

Happily, we can now judge for ourselves with the acquisition of these new volumes.

See also, Matthew Young, The Rise and Fall of the Printers’ International Specimen Exchange (New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2012). Graphic Arts RCPXG-7033164.