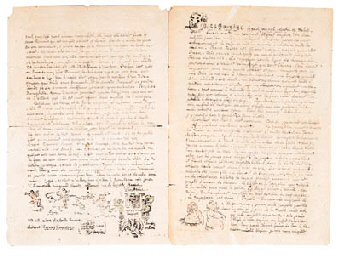

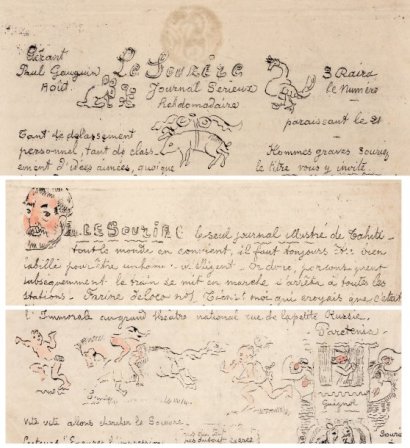

Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), Le sourire [Smiling], n° 1 (août 1899)-n° 9 (avril 1900). Edition approximately 30. (c) Drouot, Paris.

To reproduce the handwritten sheets, Gauguin used one of the newest printing devices, all the rage in Paris and New York: Thomas Edison’s mimeograph machine.

To reproduce the handwritten sheets, Gauguin used one of the newest printing devices, all the rage in Paris and New York: Thomas Edison’s mimeograph machine.

“J’ai créé un journal Le Sourire autographié, système Edison,” wrote Gauguin, “qui fait fureur. Malheureusement, on se le repasse de main en main, et je n’en vends que très peu.” (December 1899). Although Princeton does not hold copies of Sourire, we are fortunate to have one of Edison’s machines.

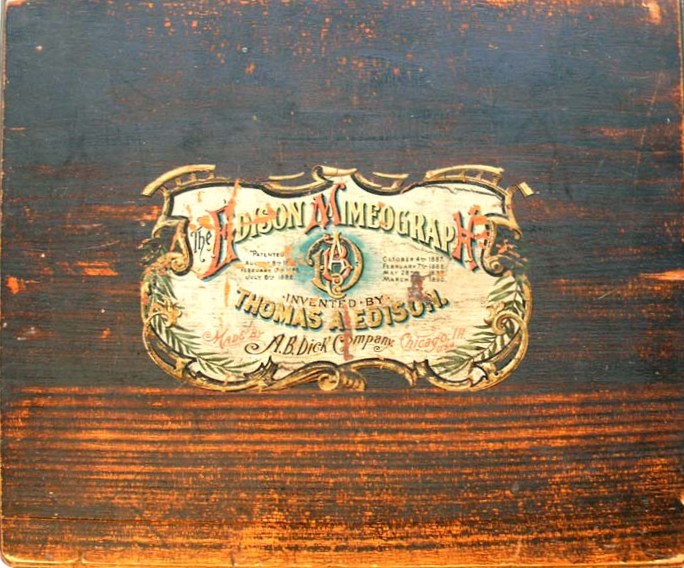

In 1876, Thomas A. Edison (1847-1931) filed a United States patent for autographic printing by means of an electric pen. A second patent further developed his system to “prepare autographic stencils for printing.”

Albert Blake Dick (1856-1934) licensed the patent and began manufacturing equipment to make stencils for the reproduction of hand-written text. In 1887, the A.B. Dick Company released the model “0” flatbed duplicator selling for $12. It was an immediate success. Dick named the machine The Edison Mimeograph.

It is model “0” that we hold in the graphic arts collection, including the original box, a printing frame (missing the screen), inking plate, ink roller, a tube of ink, and a tube of waxed wrapping paper. One container is empty, perhaps for a stylus and/or other writing tools.

The Edison Mimeograph Machine (Chicago: A.B. Dick Company, ca.1890). Gift of Douglas F. Bauer, Class of 1964. Graphic Arts Collection.

Hear Starr Figura’s commentary on Gauguin’s newspaper here: http://uat.moma.org/explore/multimedia/audios/384/6676. Her exhibition catalogue includes an essay by Hal Foster, Townsend Martin, Class of 1917, Professor of Art and Archaeology. Co-Director, Program in Media and Modernity, Princeton University.