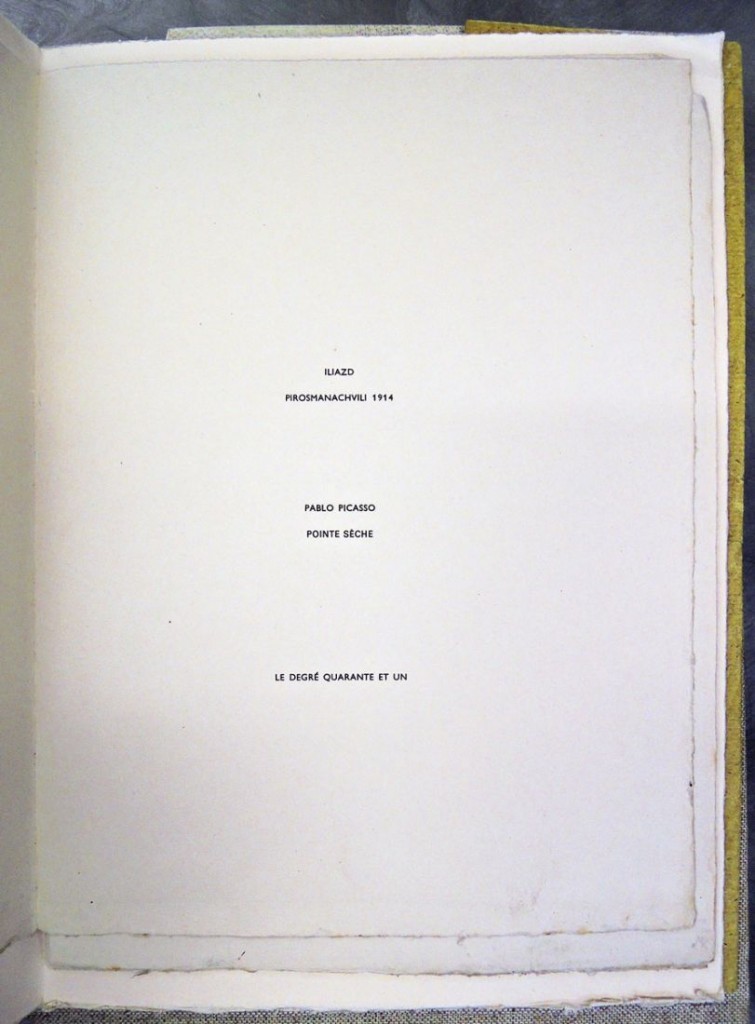

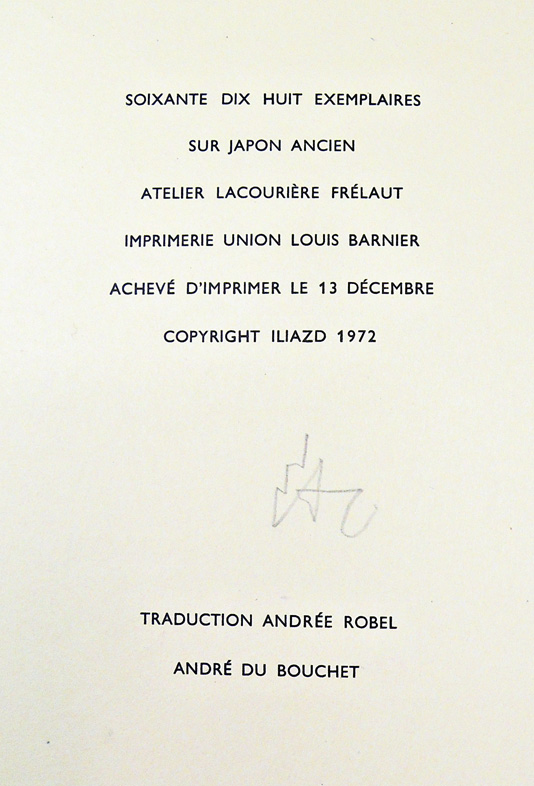

Iliazd (Ilya Zdanevich, 1894-1975), Pirosmanachvili 1914 (Paris: Le Degré 41, 1972). Original vellum binding, with yellow dust-wrapper and preserved in publisher’s beige cloth chemise and slipcase. Presentation copy from Iliazd’s last wife to Chota Takaishvili. One of 78 copies printed on Japon ancien paper, signed in red pencil on the colophon by Iliazd and with the original etching signed by Picasso, printed by Atelier Lacourière Frélaut. Graphic Arts Collection GAX in process

Iliazd (Ilya Zdanevich, 1894-1975), Pirosmanachvili 1914 (Paris: Le Degré 41, 1972). Original vellum binding, with yellow dust-wrapper and preserved in publisher’s beige cloth chemise and slipcase. Presentation copy from Iliazd’s last wife to Chota Takaishvili. One of 78 copies printed on Japon ancien paper, signed in red pencil on the colophon by Iliazd and with the original etching signed by Picasso, printed by Atelier Lacourière Frélaut. Graphic Arts Collection GAX in process

“It was something of a secret after World War II that one of the most rewarding people in Paris was a man who liked to be addressed simply as Iliazd,” wrote John Russell for the New York Times. “He was known—when known at all—as the architect, designer and publisher of illustrated books in which, one after another, the great surviving names of the School of Paris played a part.” Russell goes on to assert that Iliazd excelled “as poet, geographer, book designer, mountain climber, printer, publisher, fabric designer for Sonia Delaunay and Coco Chanel, pioneer dismantler of language, idiosyncratic stage performer and organizer in the early 1920’s of some of the last of the great classic artists’ balls.” All true.

“It was something of a secret after World War II that one of the most rewarding people in Paris was a man who liked to be addressed simply as Iliazd,” wrote John Russell for the New York Times. “He was known—when known at all—as the architect, designer and publisher of illustrated books in which, one after another, the great surviving names of the School of Paris played a part.” Russell goes on to assert that Iliazd excelled “as poet, geographer, book designer, mountain climber, printer, publisher, fabric designer for Sonia Delaunay and Coco Chanel, pioneer dismantler of language, idiosyncratic stage performer and organizer in the early 1920’s of some of the last of the great classic artists’ balls.” All true.

Born Ilia Zdanevitch in Tiflis, Georgia, Iliazd (1894-1975) was a founding member of the Russian Futurists. Like many of his contemporaries, the artist eventually made his way to Paris where he designed and published extraordinary livres d’artistes, including several with his own prose and poetry under the imprint Le Degré 41 (41 degrees refers to the latitude of his hometown, the alcoholic content of brandy, and the Celsius measure of the point at which fever leads to delirium).

Born Ilia Zdanevitch in Tiflis, Georgia, Iliazd (1894-1975) was a founding member of the Russian Futurists. Like many of his contemporaries, the artist eventually made his way to Paris where he designed and published extraordinary livres d’artistes, including several with his own prose and poetry under the imprint Le Degré 41 (41 degrees refers to the latitude of his hometown, the alcoholic content of brandy, and the Celsius measure of the point at which fever leads to delirium).

From 1940 to 1974, Iliazd produced 20 extraordinary books, including 9 with Pablo Picasso (1881-1973). None have been collected by Princeton University until now.

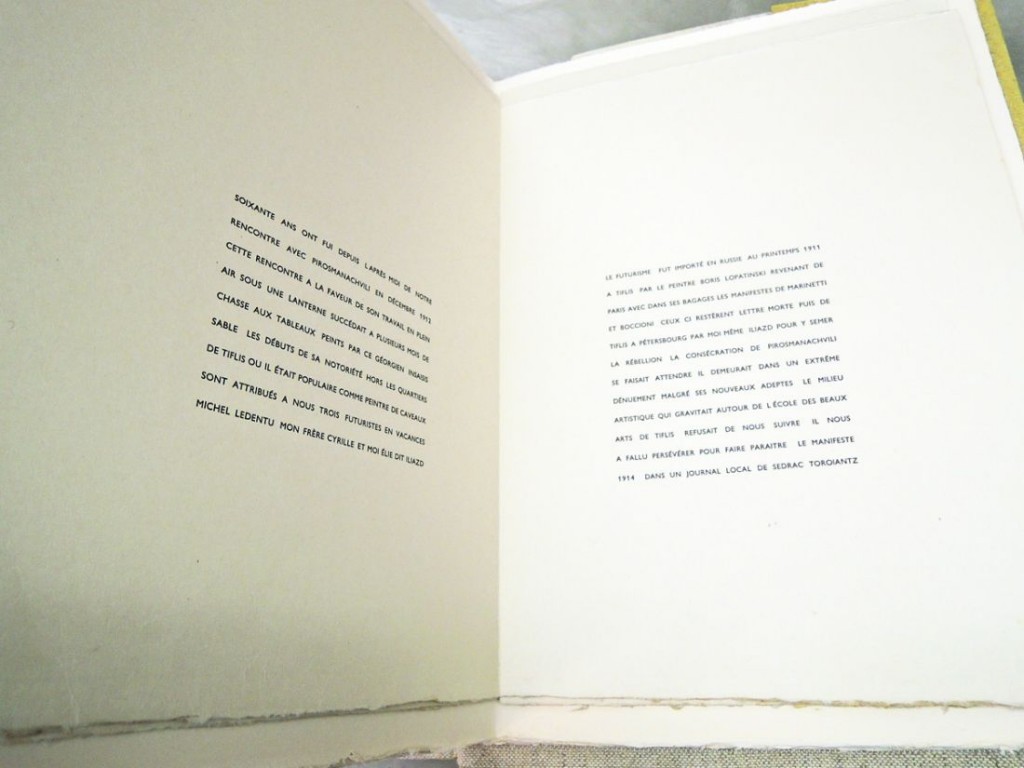

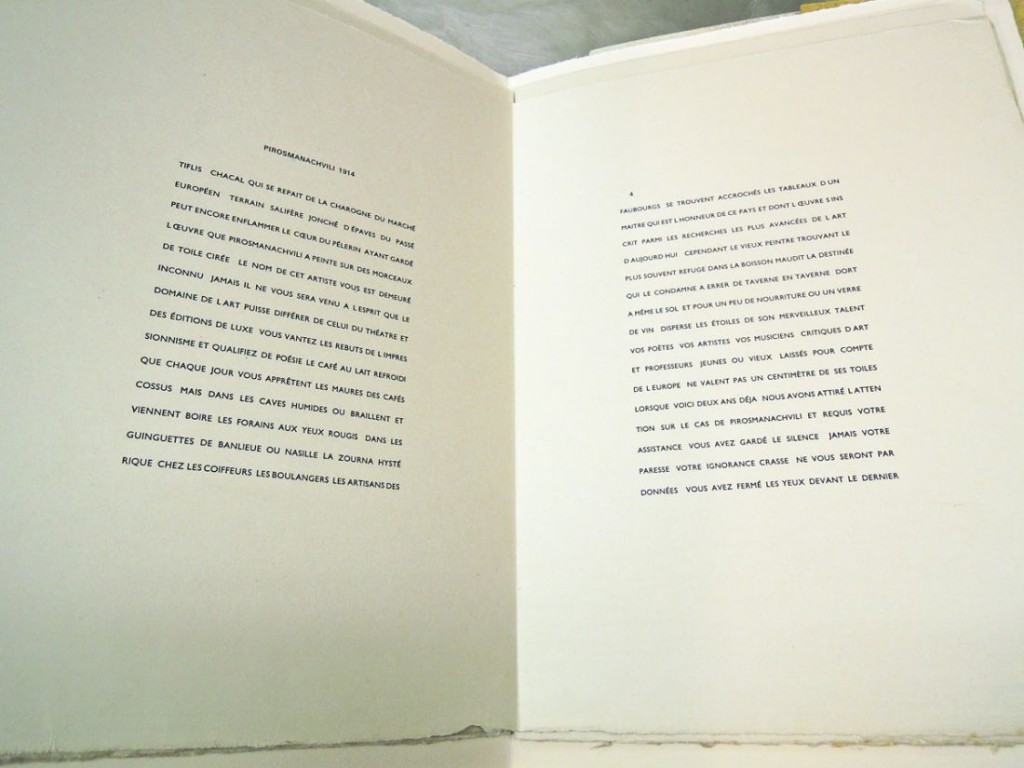

According to Bookvica, a rare book shop from Iliazd’s hometown of Tiflis, “Iliazd returned to his homeland in 1912 and with his brother, artist Kirill Zdanevitch, he met Georgian painter Niko Pirosmani (1862-1918). They became very enthusiastic about him.

Iliazd was alarmed by the difficult economic straits that the painter was in and wrote a manifesto to promote his art; it was published in a local paper Zakavkazskaya Rech’ in 1913 under the title “Khudozhnik-samorodok” (A natural-born artist). It was Iliazd’s first publication. In June 1914 the journal Vostok published his article “Niko Pirosmani,” in which he mythologized the biography of the older artist, linking him with the Silver Age and the Russian avant-garde.”

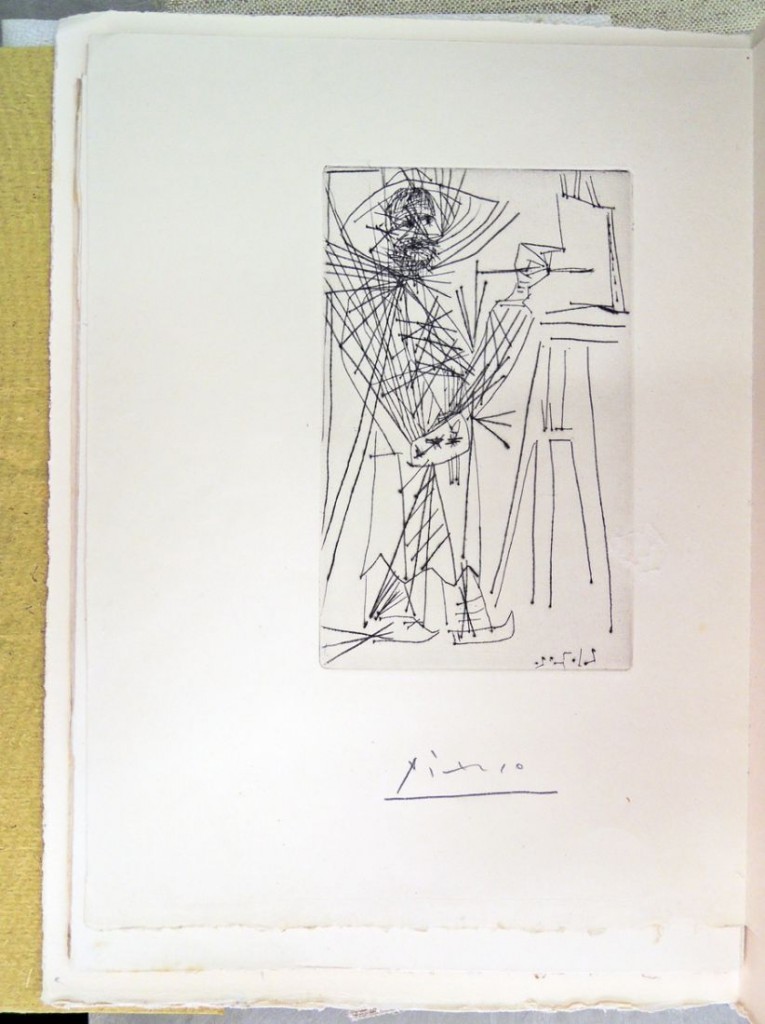

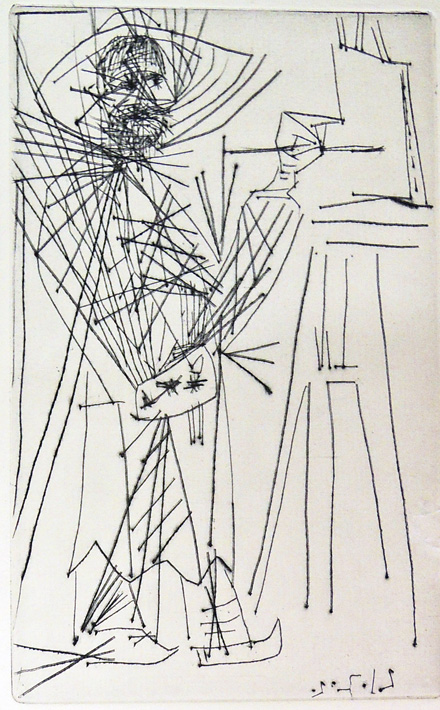

In the summer of 1971, Iliazd decided to reprint the article and to help promote it, he asked Picasso to etch the frontispiece. His friend agreed and produced a beautiful drypoint, which was printed at the Atelier Lacourière Frélaut (originally the studio of Roger Lacourière, who passed it on to his collaborator and successor Jacques Frélaut in 1957).

In the summer of 1971, Iliazd decided to reprint the article and to help promote it, he asked Picasso to etch the frontispiece. His friend agreed and produced a beautiful drypoint, which was printed at the Atelier Lacourière Frélaut (originally the studio of Roger Lacourière, who passed it on to his collaborator and successor Jacques Frélaut in 1957).

The edition of 78 was completed and signed by December 1972, four months before Picasso’s death. Although this was also intended to be Iliazd’s last book, technical difficulties on another project, Courtisan Grotesque (which had been finished in 1974), caused it to be printed after Pirosmanachvili.

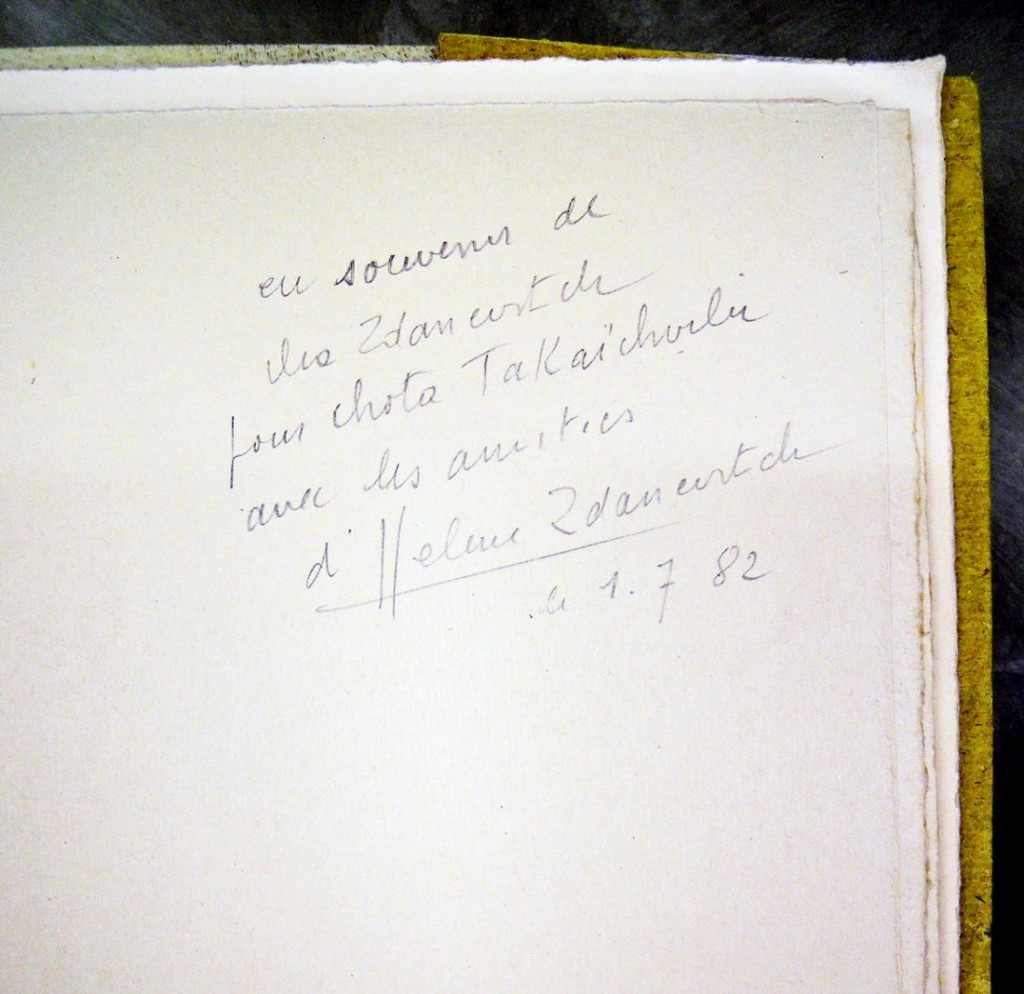

The copy now in the Princeton University Library comes from the collection of Damian Alaniya. This collector once erased the owner’s stamp of the previous owner to whom this copy was presented by the Iliazd’s wife with signature on the front endpaper: “Eu souvenir de Ms Zdanevitch pour Chota Takaishvili avec les amitiés Ms Helene Zdanevitch. 1.7.82.”

The copy now in the Princeton University Library comes from the collection of Damian Alaniya. This collector once erased the owner’s stamp of the previous owner to whom this copy was presented by the Iliazd’s wife with signature on the front endpaper: “Eu souvenir de Ms Zdanevitch pour Chota Takaishvili avec les amitiés Ms Helene Zdanevitch. 1.7.82.”

Johanna Drucker writes, “Drawing to the end of his energies, Iliazd had evidently wished this book to perform a double closure: as the end of the cycle of large books, and as the close of the full cycle of his life’s work. There was a mirroring effect between the beginning and the end, a deliberate, marked recognition of the self-consciousness which had dictated the construction of the oeuvre as a whole.” “Iliazd and the Book as a Form of Art,” The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts 7 (Winter 1988): 36-51.