Between the time of William Miller’s 9th edition and Thomas Tegg’s 4th edition of James Beresford’s massive best-seller Miseries of Human Life, the author took time out to write something else. But rather than continue to write about fictional characters, he bravely (or brutally) chose to publicly satirize one of his Oxford colleagues Thomas Dibdin.

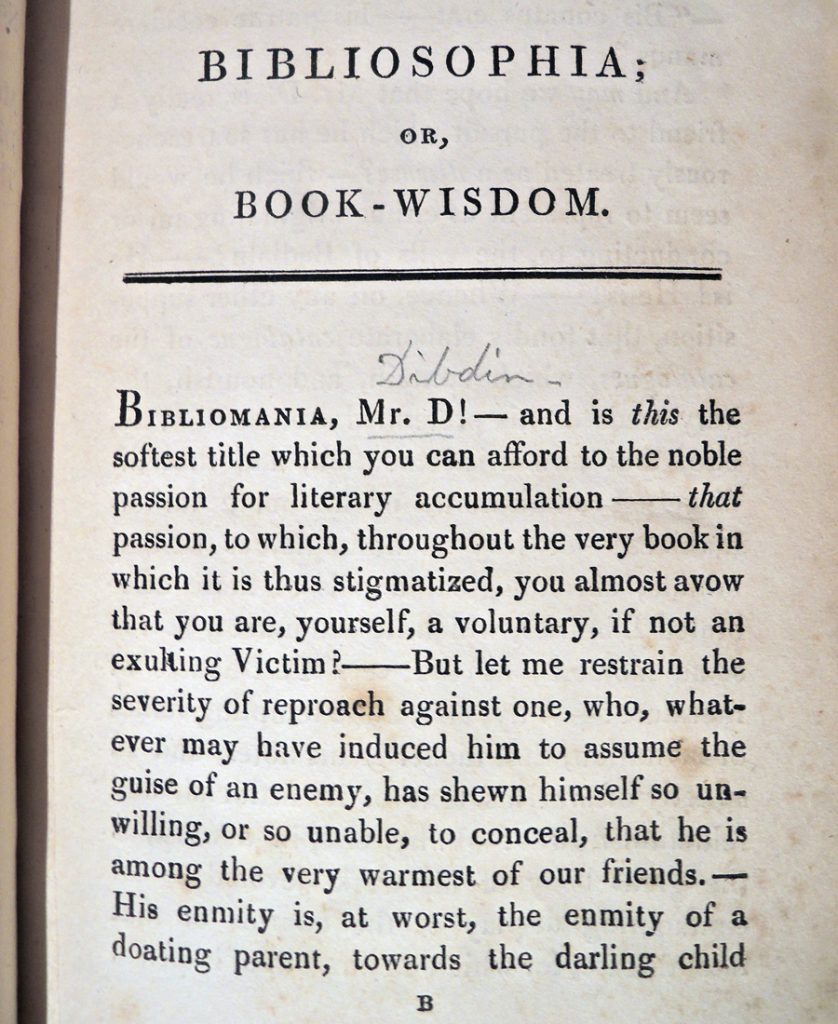

Bibliomania had been released the year earlier, to some success. Beresford jumped on it and in Bibliosophia or Book-Wisdom, he chronicled in minute detail the improper and unseemly elements of Dibdin’s work. Although Beresford’s name was not included on the title page, the identity of the author was not a secret.

Given his notoriety with Miseries, Beresford must have known that people would read and listen to his opinions. In fact, the attention he gave Bibliomania may have inadvertently given it the boost it needed and an even larger edition was published the following year.

In Matthew Beros’s book Bibliomania: Thomas Frognall Dibdin and the Early 19th Century Book Collecting, he notes:

In Matthew Beros’s book Bibliomania: Thomas Frognall Dibdin and the Early 19th Century Book Collecting, he notes:

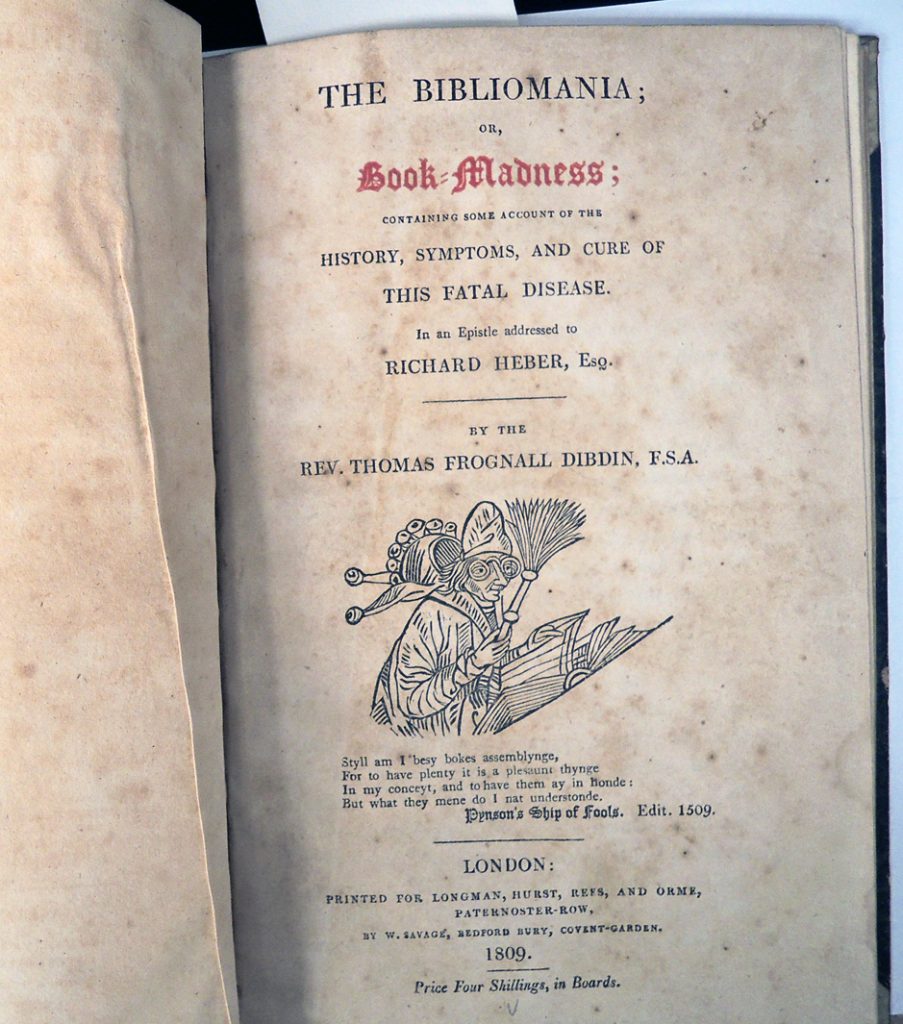

The reception of Dibdin’s book however was mixed. Thomas De Quincey and William Beckford satirised his scholarly pretensions as a bibliographer and tended to dismiss Dibdin as a self-indulgent dilettante. Part of this dismissive attitude towards The Bibliomania on the part of the literati is due to the lowly status assigned to bibliography during the 19th century. The Monthly Review deplored the ‘extravagant value placed on petty and insignificant knowledge’ such as bindings, format and paper. Also they heavily condemned the tendency for bibliomanes such as Dibdin to prefer the anecdotes of printers, publishers and purchasers to ‘historians, orators, philosophers and poets of antiquity’.

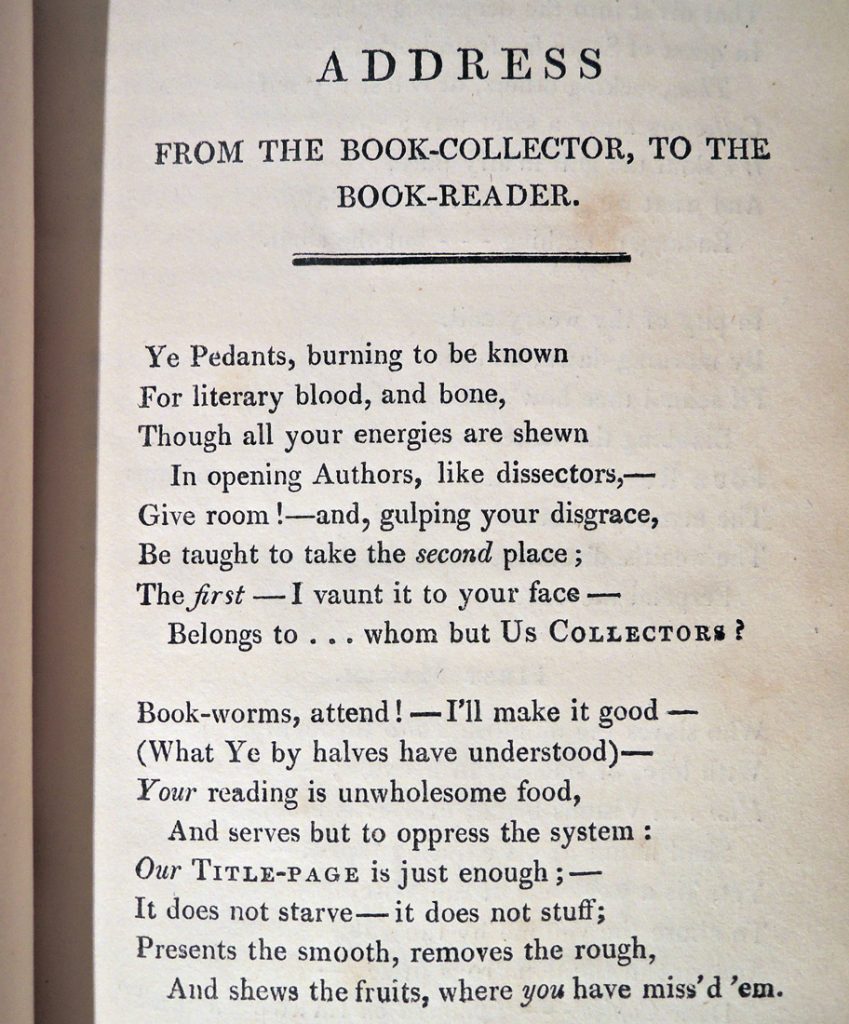

In 1810 James Beresford penned a critique Bibliosophia or Book-Wisdom which he describes as a ‘remonstrance against the prose work, lately published by Thomas Frogall Dibdin under the title The Bibliomania’. Beresford praises an appetite for collecting books which are ‘fully distinguished, wholly unconnected and absolutely repugnant to all idea of reading them’. The superiority of the collector is asserted over that of the ‘emaciated’ student who can never possess more then a ‘wretched modicum of his coveted treasures’. — https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/handle/1887/30027/TXT_Bibliomania.pdf?sequence=1

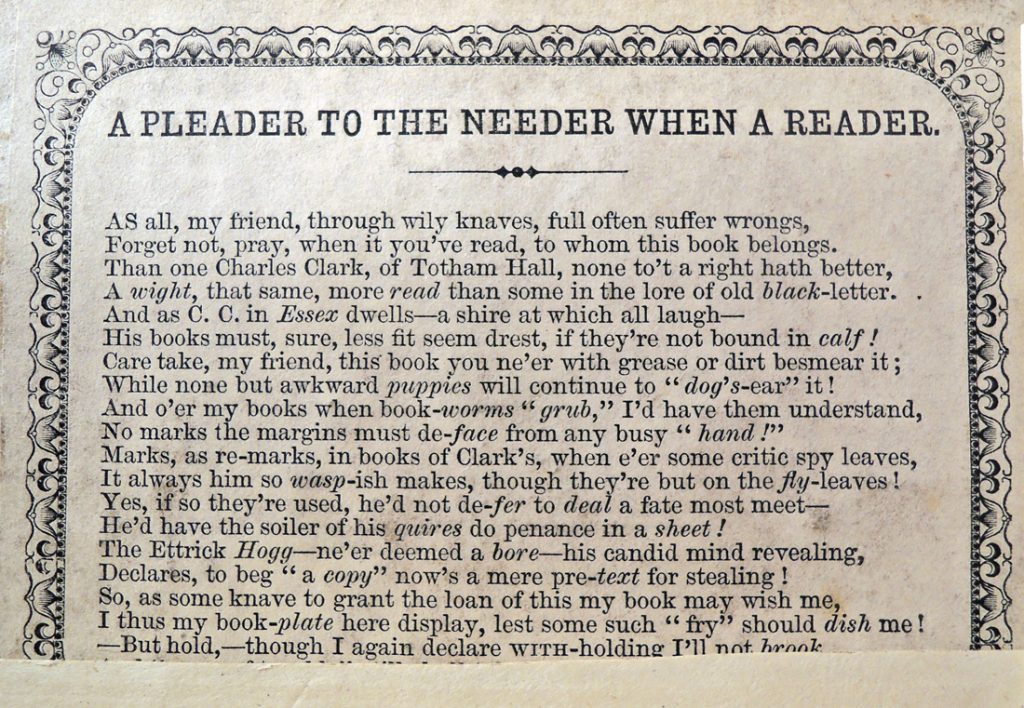

Bookplate in our copy of Bibliosophia, unfortunately cut-off by a book repair.

Bookplate in our copy of Bibliosophia, unfortunately cut-off by a book repair.

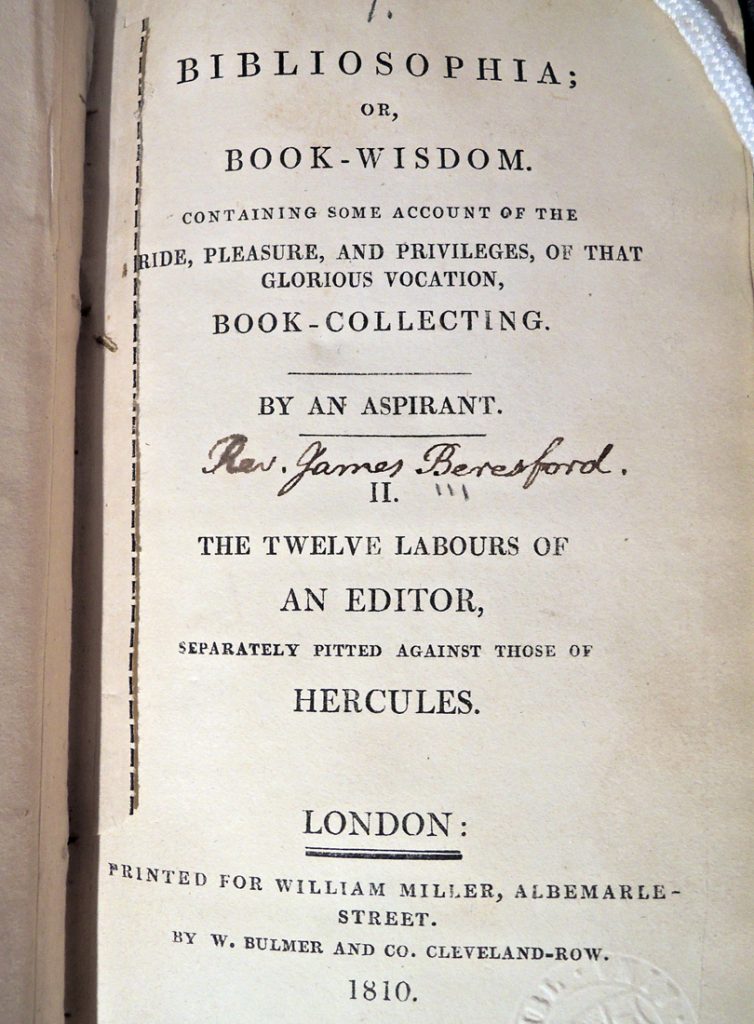

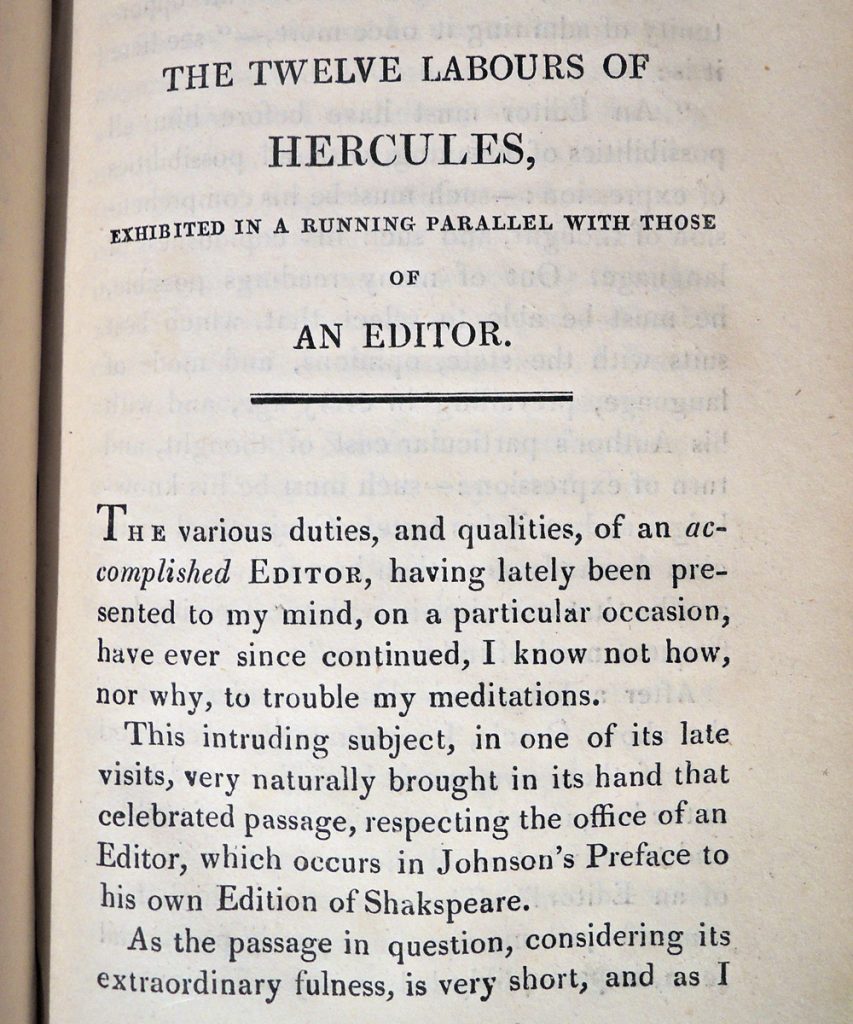

James Beresford (1764-1840), Bibliosophia; or, Book-wisdom. Containing some account of the pride, pleasure, and privileges, of that glorious vocation, book-collecting. By an aspirant. II. The twelve labours of an editor, separately pitted against those of Hercules (London: Printed for W. Miller, 1810). RECAP Z992 .B474 1810

Thomas Frognall Dibdin (1776-1847), The Bibliomania; or, Book-Madness; containing some account of the history, symptoms and cure of this fatal disease, in an epistle addressed to Richard Heber, esq. (London: Printed for Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, by W. Savage, 1809). Rare Books (Ex) 0511.298

Pingback: Merkwaardig (week 49) | www.weyerman.nl