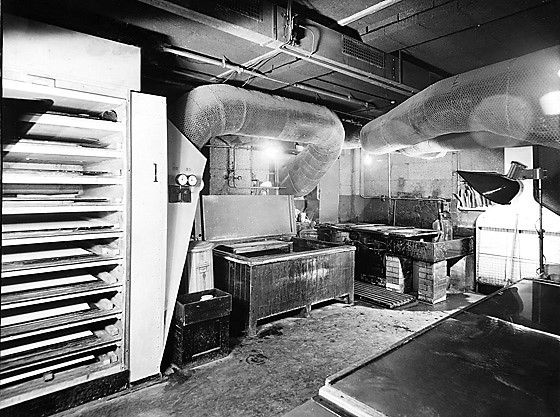

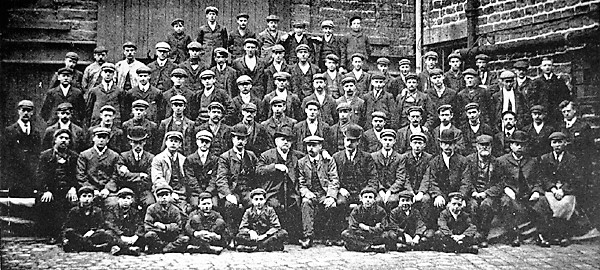

The Rembrandt Intaglio Printing Company staff pictured above, director Karl Klíč seated in the front row with his arm over Samuel Fawcett’s shoulder.

The Rembrandt Intaglio Printing Company staff pictured above, director Karl Klíč seated in the front row with his arm over Samuel Fawcett’s shoulder.

“When the whole history of rapid photogravure comes to be written (as I doubt greatly if it ever will be) it will be one of the oddest stories in the whole annals of our craft, and even today the oddities continue. Besides revelations exciting a smile, there might perhaps be revelations of some things of which complaint could at the time have fairly been made.” J. Albert Hepps, Printing Art 20 (1913).

Around 1879, Karl Klíč (1841-1926) perfected the engraving of copper plated cylinders instead of flat plates, in an attempt to speed up the slow process of photogravure. Although it was very expensive to engrave a single cylinder, once it was finished thousands of images could be printed making it financially viable for books, magazines and newspapers.

Around 1879, Karl Klíč (1841-1926) perfected the engraving of copper plated cylinders instead of flat plates, in an attempt to speed up the slow process of photogravure. Although it was very expensive to engrave a single cylinder, once it was finished thousands of images could be printed making it financially viable for books, magazines and newspapers.

In 1895, Klíč joined Samuel Fawcett and the Storey Brothers printing firm in Lancaster to form the Rembrandt Intaglio Printing Company. Klíč convinced them to stop printing textiles and specialized instead in the reproduction of old master paintings and other art publications.

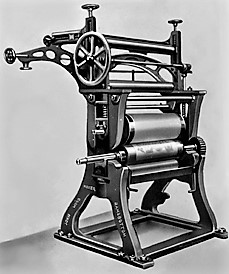

Thanks to the Sun Printers’ archive, here is a look at one of the first rotary gravure machines, a 15 in. calico printing press by John Wood of Ramsbottom, Lancaster, in 1910. (Photograph thanks to Digby Wakeman)

The Rembrandt Intaglio Printing Co., of Lancaster and London . . . were the first to introduce this class of work in 1896, and . . . they still stand unrivalled, the reputation of their work is firmly established, and they are to-day the premier company, and we admire them and their ability to keep their secret, for we believe that to this day the knowledge of “how it is done” is still theirs alone.

From the beginning the Rembrandt Intaglio process secured the highest appreciation of connoisseurs and collectors. Dr. Bode, Director of the Royal Museum, Berlin, describes their photogravures as the outcome of a perfected, and the only process which gives the richness and velvety effect of the old mezzotints.”.–Process: The Photomechanics of Printed Illustration 20, Issue 232 (1913).

One of the best examples of these rapid photogravures can be found in the two volumes of The Venture: an Annual of Art and Literature (London: J. Baillie, [1903-1905]. Rare Books 3584.932). Images are printed in black and brown inks until 1905 when Klíč succeeded in producing three-color rotogravure and the following year, his company begins marketing color gravure prints.

One of the best examples of these rapid photogravures can be found in the two volumes of The Venture: an Annual of Art and Literature (London: J. Baillie, [1903-1905]. Rare Books 3584.932). Images are printed in black and brown inks until 1905 when Klíč succeeded in producing three-color rotogravure and the following year, his company begins marketing color gravure prints.

Rembrandt Intaglio never patented rapid photogravure but kept the process secret for many years. In 1904, when Eduard Mertens filed his own patent no. 17,198 for rotary photogravure, it was rejected. Not only had pictures and type been printed intaglio from the same copper plate for hundreds of years but the Rembrandt company had clearly been printing on copper cylinders long before Mertens’ application.

The fact that Mertens photographed both the text and the pictures onto a cylinder while the Rembrandt firm engraved the words by hand made no difference.

This decision cleared the way for European and American press manufacturers to sell rotary photogravure presses and for publishers to use them. By 1910, both letterpress text and gravure images were being printed together by Freiburger Zeitung [Freiburg, Germany] and in 1912, the New York Times followed.

Dozens of printing firms were established in major cities across the globe, leaving the Rembrandt Intaglio Printing Company bankrupt. The firm was acquired by the Sun Engraving Company in 1932, renamed Rembrandt Photogravure Ltd, and maintained until it closed in 1961.

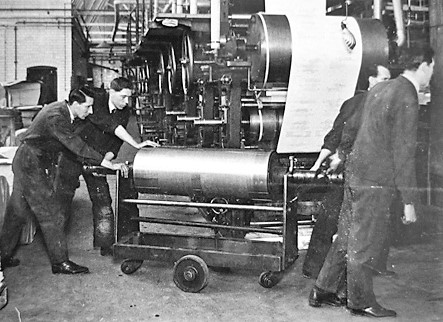

Here are a few images of the 20th-century rapid photogravure or gravure printing at Sun Engraving, thanks to their online picture archive. Note the number of men needed to move the cylinders.