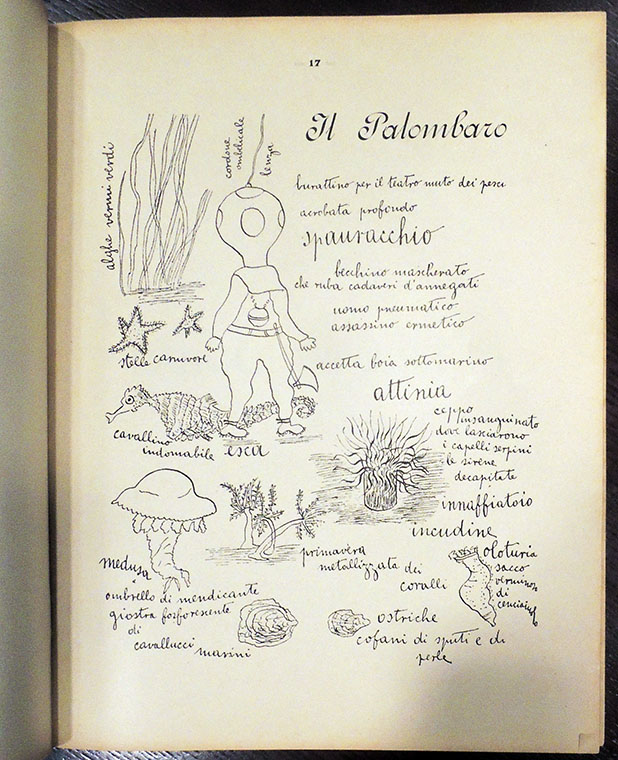

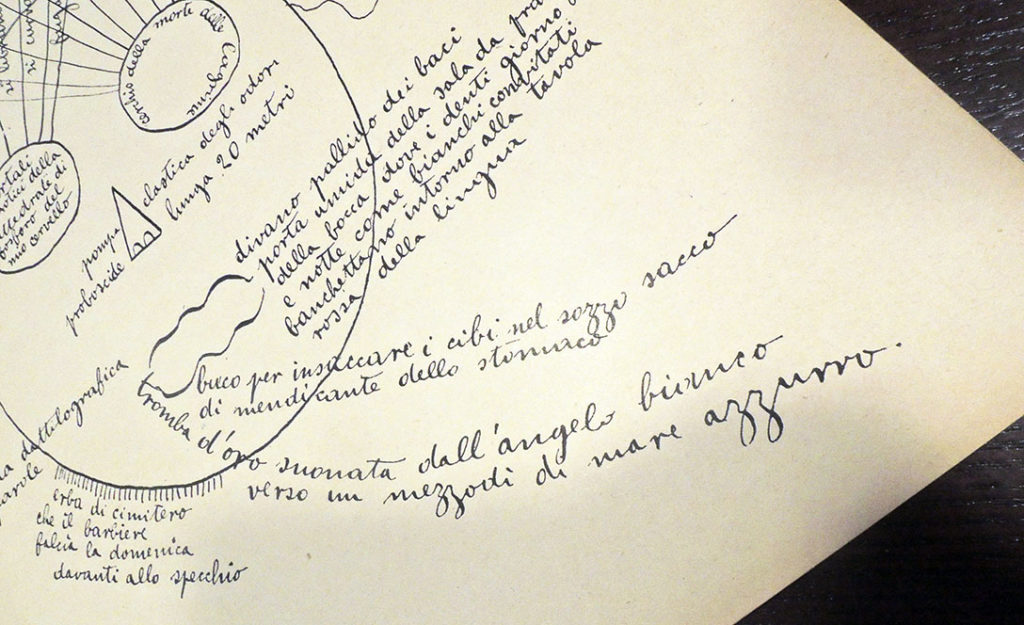

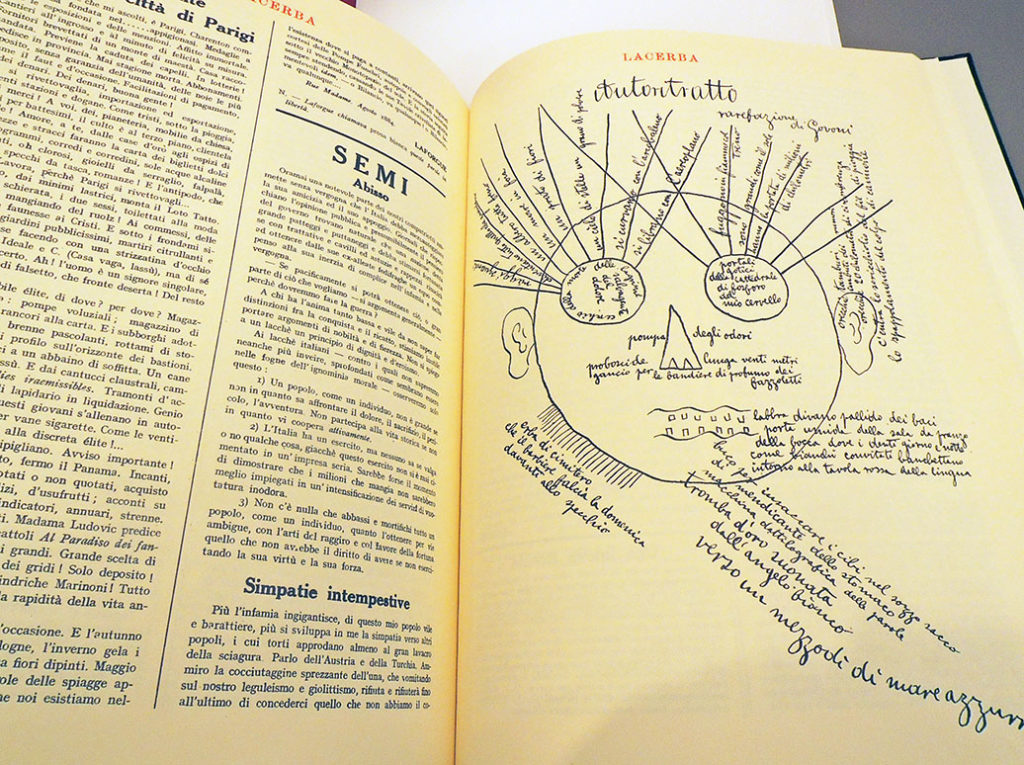

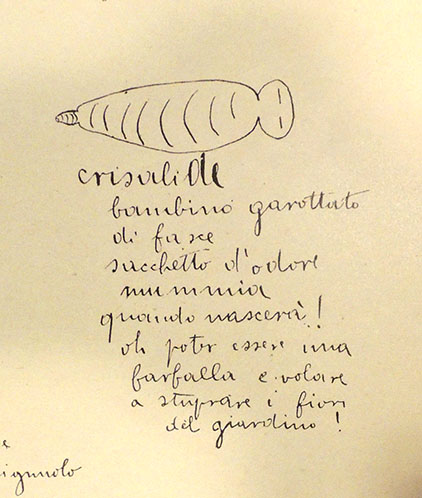

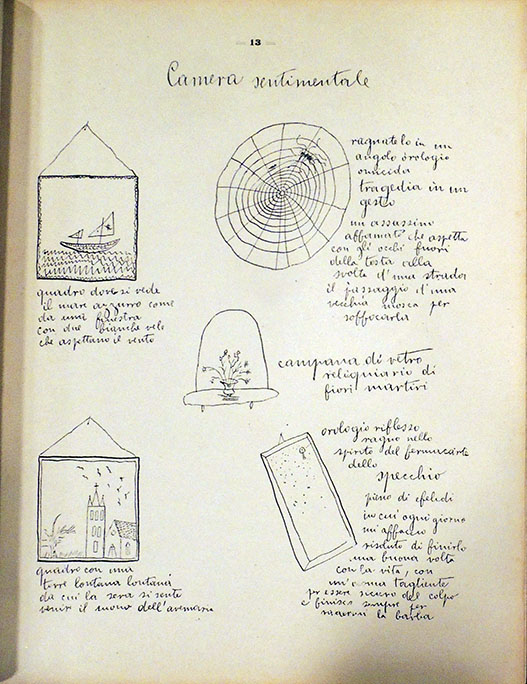

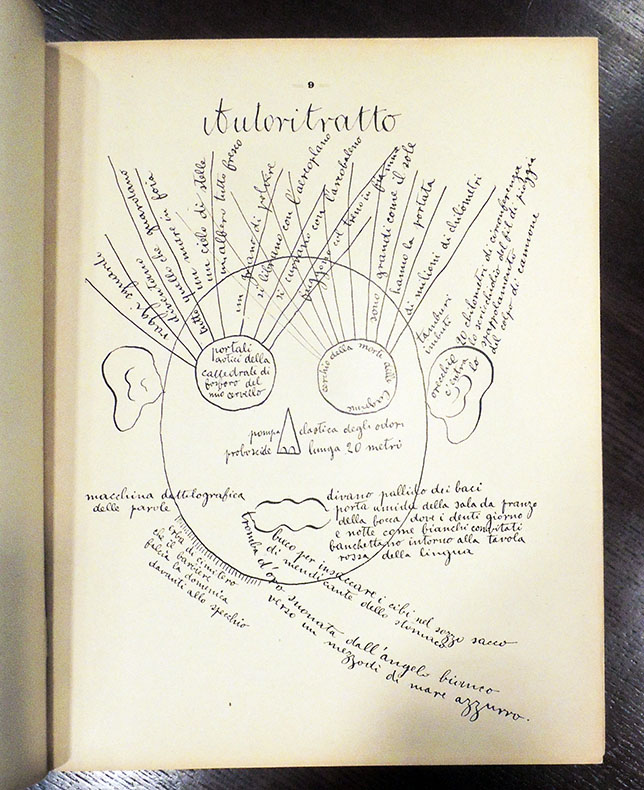

Carrado Govoni’s “Diver” (La Palombaro) first appeared in the February 11, 1915 issue of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s Parole consonanti vocali numeri in libertà. Then on March 27, 1915, the Futurist journal Lacerba published Govoni’s self-portrait, drawn with visual poetry.

Not long after this, Govoni’s book Rarefazioni e parole in libertà was published by the Marinetti’s Milan imprint Edizioni futuriste di “Poesia.” (SAX PQ4817.O8 Z4852 1915q), which included both Govoni’s Driver and his Self-portrait but this time, with slight variations in each. Why are they different? Did he decide not to have teeth for a reason? Which versions are the final, definitive work?

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876-1944) began the entrepreneurship [Parole] as “a disinterested love of art which was combined with his wish to address the need for an alternative space that could sustain the talents he wished to launch into the marketplace of art and literature: the painters Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Gino Severini, Ardengo Soffici, Fortunato Depero, Enrico Prampolini, as well as the writers Aldo Palazzeschi, Corrado Govoni, Paolo Buzzi, Luciano Folgore, Francesco Cangiullo, and many others.

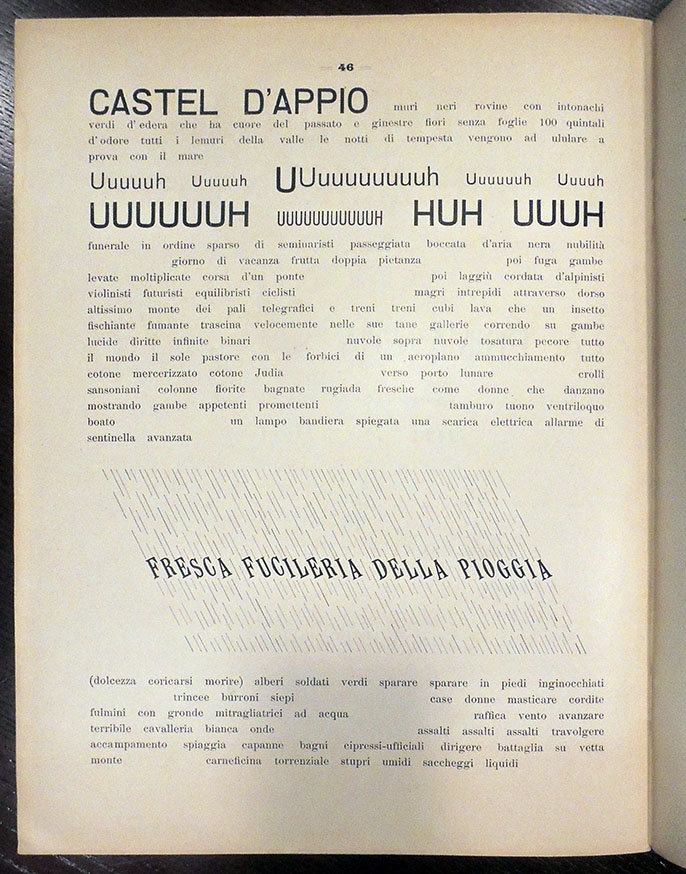

The “Futurist Editions of Poesia” were perhaps the most important embodiment of Marinetti’s desire to create an alternative cultural space, becoming an experimental laboratory in the true sense of the term, where the canons of a new writing, the “words-in-freedom,” were successively elaborated and consecrated for the first time …’We reserve the ‘Futurist Editions of Poesia’ for those works that are absolutely Futurist in their violence and intellectual extremism and that cannot be published by others because of their typographical difficulties.—Claudia Salaris, “Marketing Modernism: Marinetti as Publisher,”.Modernism/Modernity 1.3 (1994): 109-27.

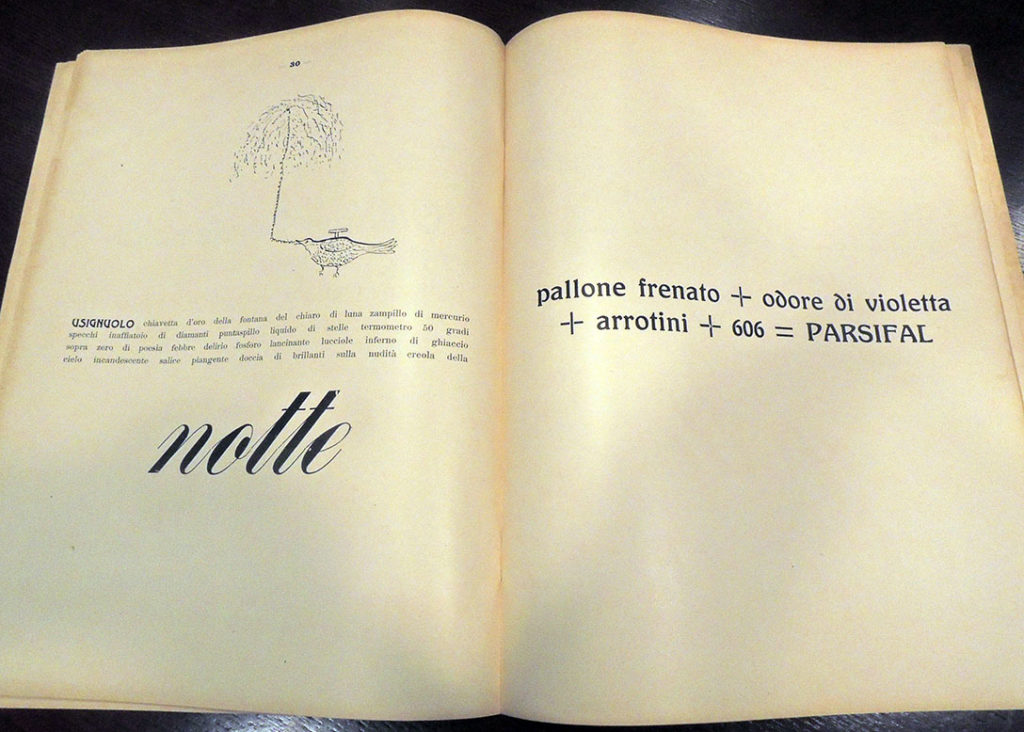

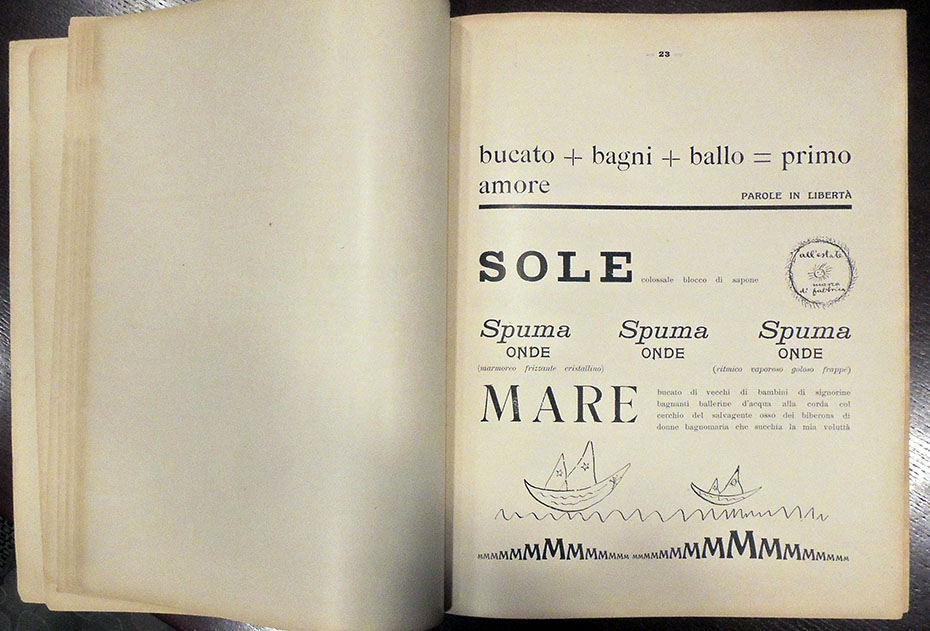

Corrado Govoni’s book, Rarefazioni e parole in libertà (Rarefactions and Words in Freedom) is divided into two parts:

“The first presented a series of experiments in visual poetry, while the second featured applications of the poetical techniques suggested by F.M. Marinetti in the “Manifesto della letteratura futurista” (Manifesto of Futurist Literature, 1912). In both instances, however, the Futurist method provided Govoni a pretext for his eclectic analogical imagery. These works were often illustrated by the poet’s own sketches or drawings, which constituted in integral part of his verse.” —Encyclopedia of Italian Literary Studies (2006)