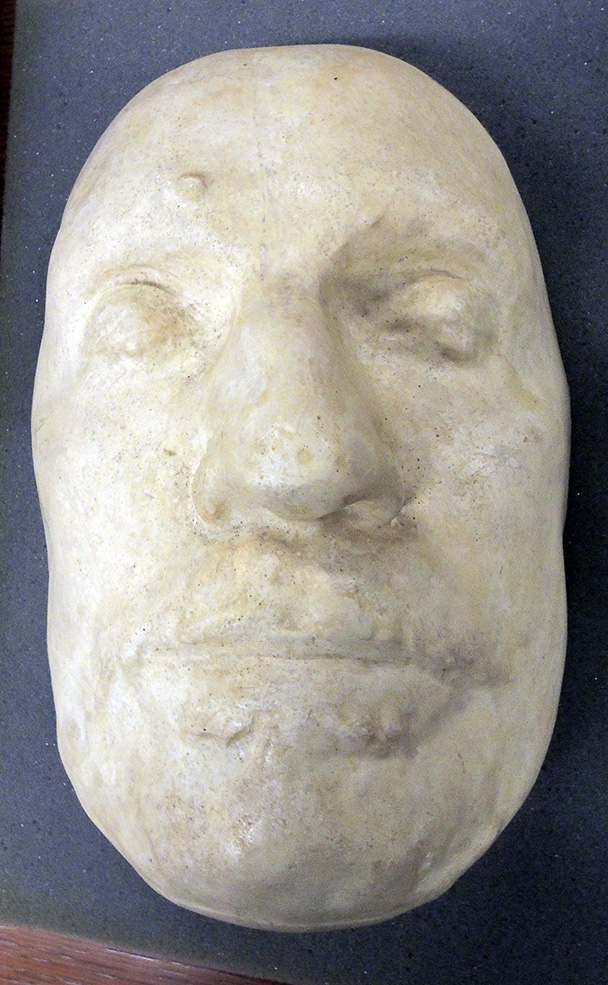

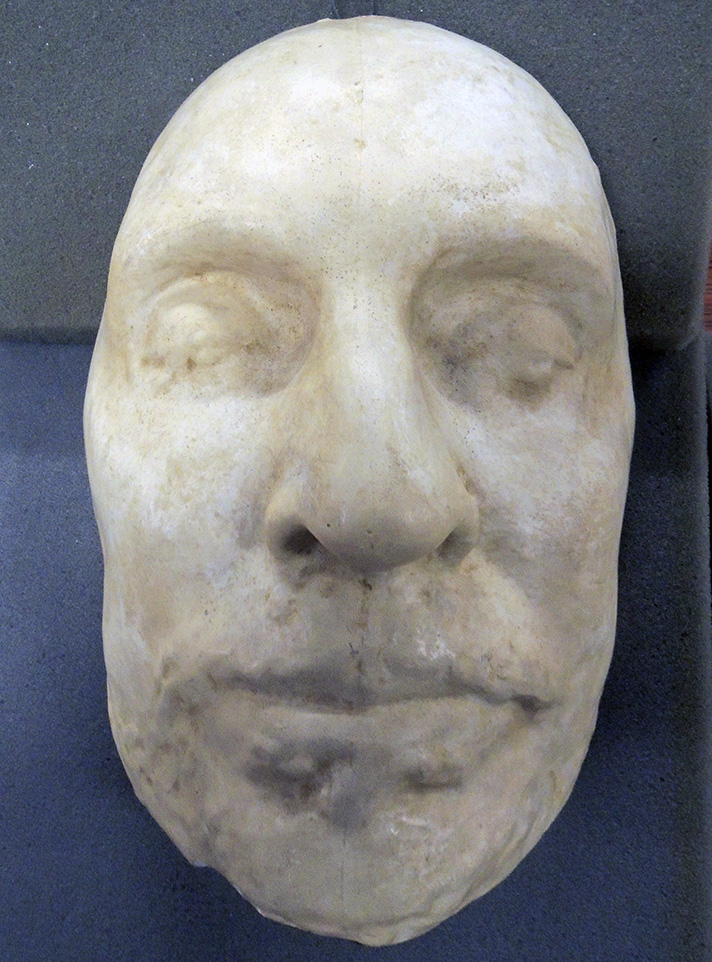

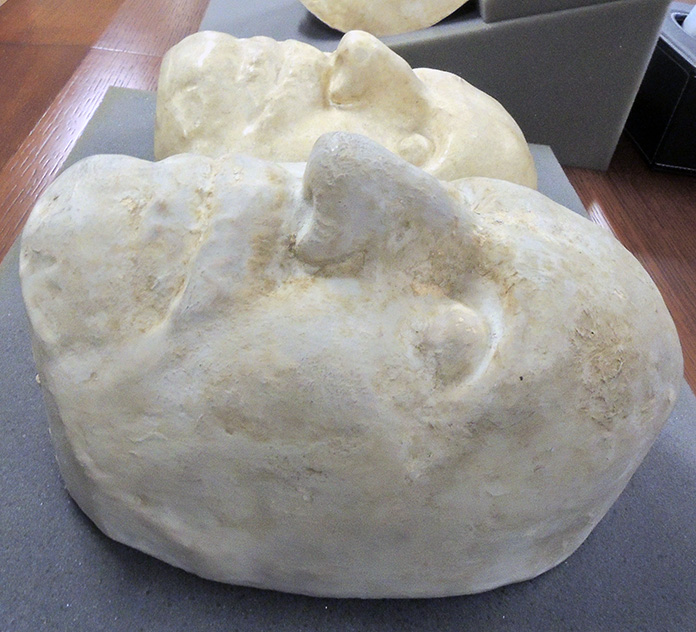

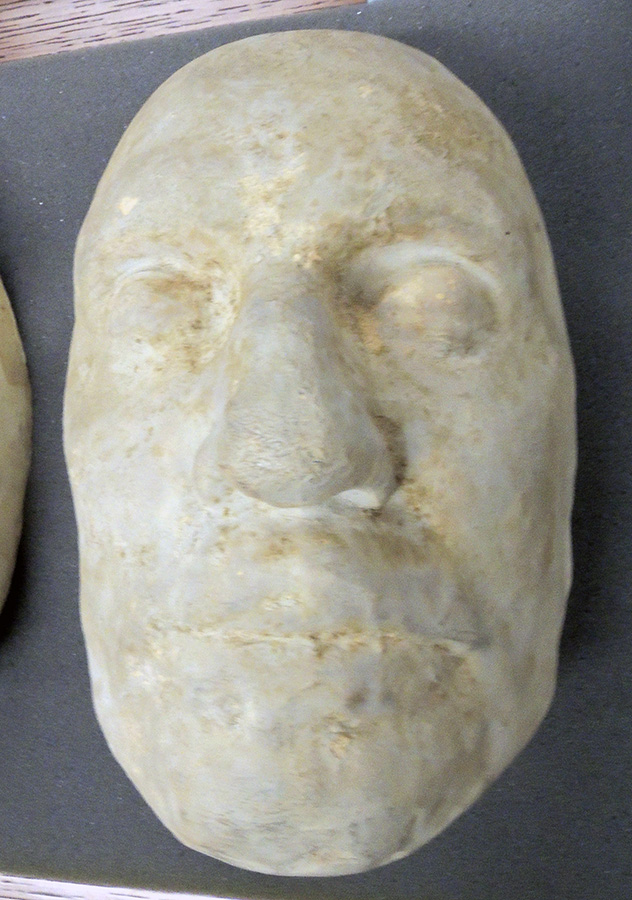

The Laurence Hutton Death Mask collection includes 3 copies of the Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) death mask from the original at the National Portrait Gallery, London. Note only one has a wart over the eyebrow. Hutton wrote about them in Portraits in Plaster, pp. 206-13, quoted here at length.

…Cromwell, according to the Commonwealth Mercury of November 23, 1658, was buried that day at the east end of the chapel of Henry VII., in Westminster Abbey. Dean Stanley accepted this as an established fact, notwithstanding the several reports, long current, that the body was thrown into the Thames, or laid in the field of Naseby, or carried to the vault of the Claypoles in the parish church of Northampton, or stolen during a heavy tempest in the night, or placed in the coffin of Charles I. at Windsor, Mr. Samuel Pepys being responsible for the last wild statement. After the Restoration this same Mr. Pepys saw the disinterred head of Cromwell in the interior of Westminster Hall, although all the other authorities agree in stating that, with the heads of Ireton and Bradshaw, it adorned the outer walls of that building. It may be stated, by the way, that a trustworthy friend of Mr. Pepys, and a fellow-diarist, one John Evelyn witnessed “the superb funeral of the Lord Protector.”

He was carried from Somerset House in a velvet bed-of-state to Westminster Abbey, according to this latter authority; and “it was the joyfullest funeral I ever saw, for there were none that cried but dogs, which the soldiers hooted away with a barbarous noise, drinking and taking tobacco in the streets as they went.” It does not seem to have occurred to Mr. Evelyn, or to other eye-witnesses of the funeral, that this was a mock ceremonial, and that the actual body of the Protector was not in the hearse. Both Horace Smith and Cyrus Redding, early in the present century, saw what they fully believed to be the head of Cromwell. It was then in the possession of “a medical gentleman” in London. “The nostrils,” said Redding, “were filled with a substance like cotton. The brain had been extracted by dividing the scalp. The membranes within were perfect, but dried up, and looked like parchment. The decapitation had evidently been performed after death, as the state of the flesh over the vertebrae of the neck plainly showed.

A correspondent of the London Times, signing himself “Senex,” wrote to that journal, under date December 31, 1874, a full history of this head, in which he explained that at the end of five-and-twenty years it was blown down one stormy night, and picked up by a sentry, whose family sold it to one of the Cambridgeshire Russells, who were the nearest living descendants of the Cromwells. By them it was sold, and it was exhibited at several places in London. “Senex” gave the following account of the recognition of the head by Flaxman, the sculptor: “Well,” said Flaxman, I know a great deal about the configuration of the head of Oliver Cromwell. He had a low, broad forehead, large orbits to his eyes, a high septum to the nose, and high cheekbones; but there is one feature which will be with me a crucial test, and that is that instead of having the lower jawbone somewhat curved, it was particularly short and straight, but set out at an angle, which gave him a jowlish appearance. The head,” continued “Senex,” “exactly answered to the description, and Flaxman went away expressing himself as convinced and delighted.”

Another, and an earlier account, dated 1813, says that “the countenance has been compared by Mr. Flaxman, the statuary, with a plaster cast of Oliver’s face taken after his death [of which there are several in London], and he [Flaxman] declares the features are perfectly similar.” Whether or not the body of the real Cromwell was dug up at the Restoration, and whether his own head, or that of some other unfortunate, was exposed on a spike to the fury of the elements for a quarter of a century on Westminster Hall, are questions which, perhaps, will never be decided. The head which Flaxman saw, as it is to be found engraved in contemporary prints, is not the head the cast of which is now in my possession, although it bears a certain resemblance thereto. Mine is probably “the cast from the face taken [immediately] after his death,” of which, as we have seen, several copies were known to exist in Flaxman’s time. It is, at all events, very like to the Cromwell who has been handed down to posterity by the limners and the statuaries of his own court.

Thomas Carlyle was familiar with it, and believed in it, and he avowedly based upon it his famous picture of the Protector: “Big massive head, of somewhat leonine aspect; wart above the right eyebrow; nose of considerable blunt aquiline proportions; strict yet copious lips, full of all tremulous sensibility, and also, if need were, of all fierceness and rigor; deep, loving eyes, call them grave, call them stern, looking from under those shaggy brows as if in lifelong sorrow, and yet not thinking it sorrow, thinking it only labor and endeavor; on the whole, a right noble lion-face and hero-face; and to me it was royal enough.” The copy of the Cromwell mask in the Library of Harvard College is thus inscribed: “A cast from the original mask taken after death, once owned by Thomas Woolner, Sculptor. It was given by him to Thomas Carlyle, who gave it, in 1873, to Charles Eliot Norton, from whom Harvard College received it in 1881.”

A copy of this mask in plaster is in the office of the National Portrait Gallery, in Great George Street, Westminster; and a wax mask, resembling it strongly, although not identical with it, is to be seen in the British Museum. This latter, which is broken in several places, lacks the familiar wart above the right eyebrow. There is no record of either of these casts in either institution, and the authorities and experts of both have no knowledge as to how and when they found their way to their present resting-places.

Rev. Mark Xoble, in his House of Cromwell, however, said that the representative in London of Ferdinand II., of Tuscany, bribed an attendant of Cromwell to permit him to take in secret “a mask of the Protector in plaster of Paris, which was done only a few moments after his Highness’s dissolution.” “A cast from this mould,” he added, “is now in the Florentine Gallery. It is either of bronze, with a brassy hue, or stained to give it that appearance.” Elsewhere Mr. Noble said, writing in 1737, that “the baronial family of Russell are in possession of a wax mask of Oliver, which is supposed to have been taken off while he was living.” After a careful study of all the Florentine galleries in the winter of 1892-93, 1 failed to find this copy of the Cromwell mask or any record of its ever having existed there, although the Pitti Palace contains an original portrait of Cromwell from life by Sir Peter Lely, which was presented by the Protector to this same Grand Duke Ferdinand II.

see also: https://www.princeton.edu/~graphicarts/2008/10/life_and_death_masks.html