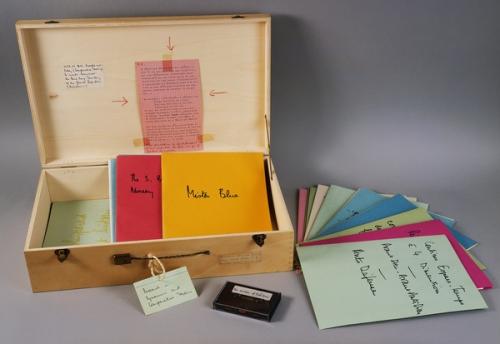

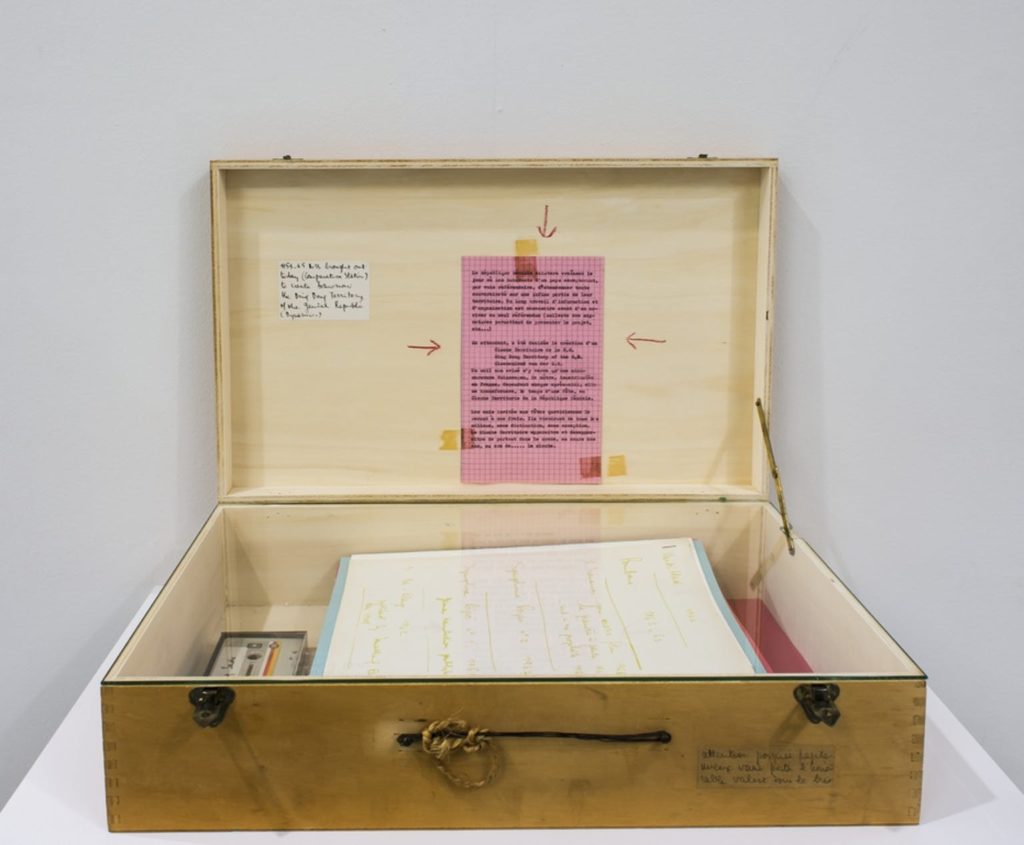

The Graphic Arts Collection recently added a rare piece of Fluxus art by Robert Filliou (1926-1987) entitled Research in Dynamics and Comparative Statics [Recherche en dynamique et statique comparée] (Bruxelles: Lebeer Hossmann, 1973). It is a wooden suitcase (50 x 31 x 12.5 cm), unvarnished, with single brass hinge screwed into right-hand side, two metal clasps at front edge, and a wire handle, supplemented by cautionary manuscript note that warns of the handle’s fragility; “mieux faut porte le honorable valise sous le bras.” The work’s title is inscribed by Filliou to a green index card, [once tied to the handle now inside the box]. To the top inside of the lid, a manuscript label reads “16704 cm3 de Pre-Territoire de la République Géniale;” green chalk measurements to the lid outline a space of 48 x 29 cm. At the bottom side of suitcase is Filliou’s signature and date in pencil.

The only other examples of this work are in France at the BnF, the Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris, and MAC Lyon. Princeton’s copy comes from Filliou’s son.

Contents inside suitcase comprise: (1) 28 folders of various colours, each featuring large manuscript labels to front covers, with approximately 248 pages of manuscript and typescript facsimiles; (2) a table of contents, in facsimile manuscript (5 pp.) [with this copy appearing to miss the penultimate page]; (3) an audio cassette, in original case, with manuscript labels to both sides A and B (“Singing Sade” and “The Wisdom of R. Filliou”); (4) a further manuscript label, affixed to inner lid: “1958-1965 Mss brought out today (comparative statics) to create tomorrow the Ding Dong Territory of the Genial Republic (dynamics)”; and (5) a typescript manifesto (in French), on a sheet of pink graph paper (30 x 21 cm.), with manuscript corrections and an additional manuscript note at bottom, where this copy is hand-numbered as 16 of 30.

Writing for the New York Times, Grace Glueck noted, “Filliou, a charter member of Fluxus, the 1960’s performance group that specialized in esthetic nonevents, believed that art didn’t have to express itself in the form of objects. He saw it as a form of play that could even occur as unrealized notions. … Ephemeral as it is, Filliou’s gadfly work refreshes by undermining heavy notions of what art is or should be. Like the French composer Erik Satie, he knew how to play with the serious.” https://www.nytimes.com/1998/07/24/arts/art-in-review-robert-filliou.html

Princeton holds a number of important works by Filliou, beginning with the 1965 Ample food for stupid thought (GAX 2006-2009N). **Note, unfortunately our library now offers images in the online catalogue that are not taken from our material but found somewhere on the internet and may not, in many cases, represent that work owned by our library. Generic pictures of a book jacket are one thing, but works of graphic art frequently differ in significant ways from one impression to another. The image pictured with Ample Food is not the copy in the Princeton University Library.

At one time, Filliou and his friends managed their own gallery along the French Riviera, near the French-Italian border. “The Smiling Cedilla was a non-shop,” commented the artist, “because it was only open on demand. This Centre of Permanent Creation, by George Brecht, Marianne Staffeldt, Donna Brewer and myself, opened in Villefranche-sur-Mer in 1965 and lasted three years. Our activities were multiple. They were summarized in the book Games at the Cedilla, or The Cedilla Takes Off (Something Else Press, New York, 1967). When the Smiling Cedilla closed its doors, it announced the birth of the “Eternal Network, La Fête permanente.”

At one time, Filliou and his friends managed their own gallery along the French Riviera, near the French-Italian border. “The Smiling Cedilla was a non-shop,” commented the artist, “because it was only open on demand. This Centre of Permanent Creation, by George Brecht, Marianne Staffeldt, Donna Brewer and myself, opened in Villefranche-sur-Mer in 1965 and lasted three years. Our activities were multiple. They were summarized in the book Games at the Cedilla, or The Cedilla Takes Off (Something Else Press, New York, 1967). When the Smiling Cedilla closed its doors, it announced the birth of the “Eternal Network, La Fête permanente.”

The box now in the Graphic Arts Collection comes from the period Filliou called The Eternal network, a movement when neither he nor his work had a permanent home.

Here is a bit more of his interesting history taken from: https://metropolis.free-jazz.net/robert-filliou-art-is-what-makes-life-more-interesting-than-art/artist-portraits/70/

In 1943, Robert Filliou joined the Resistance movement organized by the communists and became a member of the French Communist Party during the war (he would later leave it after Tito’s exclusion for the Communist International). In 1947, he went to the United States to meet his father who he had never known. After working as a labourer for Coca Cola in Los Angeles, he began to study (while continuing to do “odd jobs” to earn his living) and achieved a masters in economics.

… In Paris, in the Contrescarpe area, Daniel Spoerri introduced him to the world of the plastic artists. This was in the middle of the boom of the 1960s, with the return in strength of Duchamp’s ideas, the appearance of Fluxus and the effervescent avant-garde of the Nouveaux Réalistes. … In 1962, determined to remain outside the exhibition circuit, Robert Filliou carried his gallery in his hat. He became his own exhibition space: “La Galerie Légitime” [The Legitimate Gallery]. His works, gathered together in his beret and stamped “Galerie Légitime Couvre Chef d’Oeuvre” [Legitimate Gallery Masterpiece Hat], circulated in the streets with him (the idea is reminiscent of Marcel Duchamp’s suitcase). He then met George Maciunas, the centralizer of the activities of Fluxus.

… In 1965, with George Brecht, Robert Filliou founded the gallery “La Cédille qui sourit” [The Smiling Cedilla) in Villefranche-sur-Mer, although it was usually closed because the artists were at the local café: “In my opinion, that’s where you get your best ideas”.

In his book-length interview with Lebeer (Secret of permanent creation), Filliou repeatedly refers to this box as a failure. “If I could, I’d give people their money back. If I could find a way I’d do that. Because what I said I was going to do I haven’t done. I had the feeling I got the money under false pretences.” Lebeer, as publisher, repeatedly assures him that sales were positive; Dieter Roth was one of the first buyers, stating “one day Filliou will be a great classical poet.”