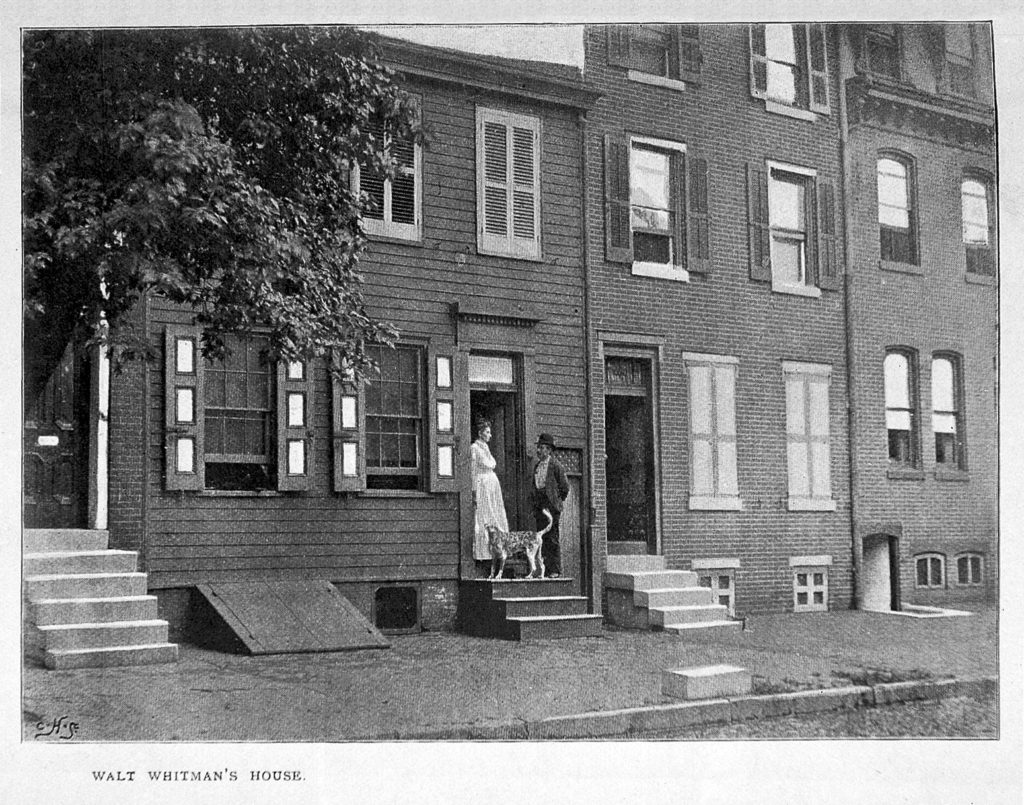

At 2:00 p.m. on Friday, June 26, 2020, you are invited to join the second live webinar highlighting Special Collections at Firestone Library, Princeton University. Register here. The topic, “Thomas Eakins and the Making of Walt Whitman’s Death Mask,” was chosen specifically for June, LGBTQ pride month and this year, the 50 anniversary of the first march. Both Walt Whitman (1819-1892) and Thomas Eakins (1844-1916), in their own way, broke down barriers around sex, sexuality, and the celebration of the human body, working in staunch opposition to the genteel status quo of the 19th century. Their friendship did not begin until the last five years of Whitman’s life but once they met, Eakins became a frequent guest at the poet’s Camden, New Jersey, home where Whitman was chiefly confined.

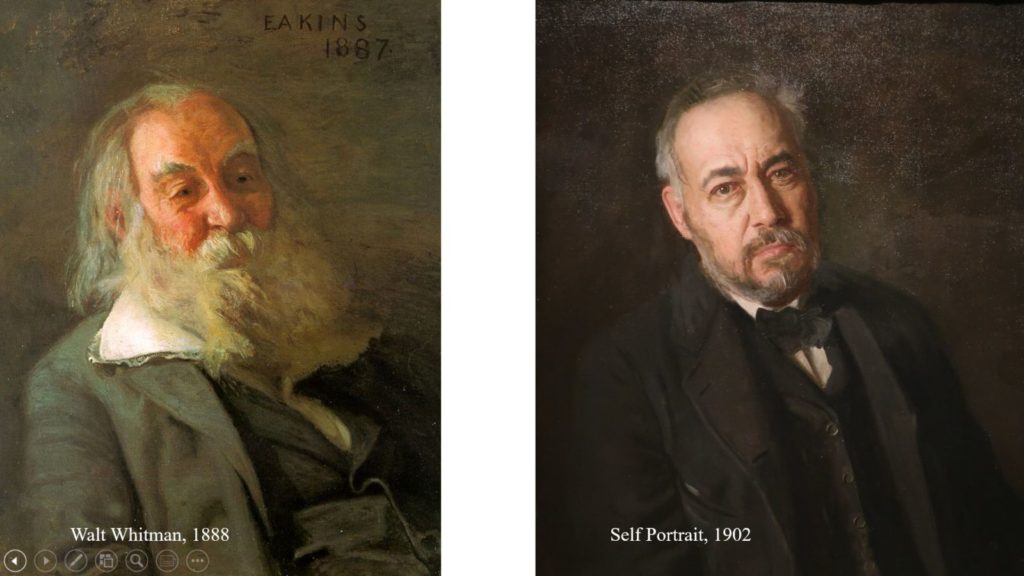

Their lives were punctuated by scandal and national disgrace, followed by even worse, periods of neglect. Just as Whitman faced rejection by publishers and critics, Eakins endured equal censure from curators and collectors. Yet each found a way to work independent of institutional patronage and pursue their own search for truth. Whitman wrote, “I never knew of but one artist, and that’s Tom Eakins, who could resist the temptation to see what they think ought to be rather than what is.”

For his part, Eakins painted a self-portrait that echoes the pose, the hue, and the sentiment in the portrait he painted of Whitman, visually coupling their images for eternity.

. . . Several months before Whitman’s death, Eakins and his partner went to Camden to practice on Whitman himself, casting his right hand in plaster. They probably left supplies in his home, anticipating what would soon be necessary. On March 26, 1892, Eakins and Sam Murray were notified of the poet’s death and early the next morning crossed the Delaware River to his house.

Working slowly and carefully over three hours, they gently oiled Whitman’s face and body, thickly coating his beard and eyebrows so they wouldn’t stick to the plaster. His ears, brows, and other features would be sculpted later and added to various plaster casts. Molds were made of the front and back of the head along with Whitman’s shoulders so a complete bust could be formed.

There is more to the story. Please join us. For a zoom address, just register here. We are holding this early in the afternoon so as not to distract from protests or demonstrations later in the day. Thanks.