The National Typographical Union was founded in 1852 and renamed the International Typographical Union (ITU) in 1869, the same year the first female printers were accepted as members.

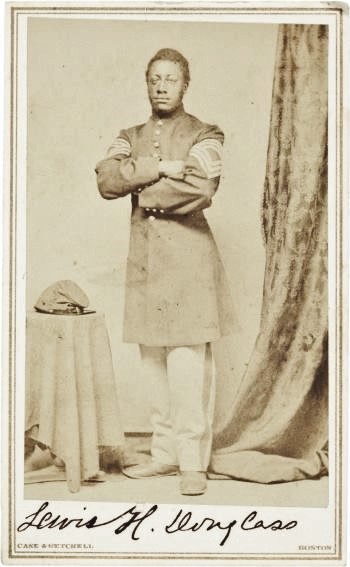

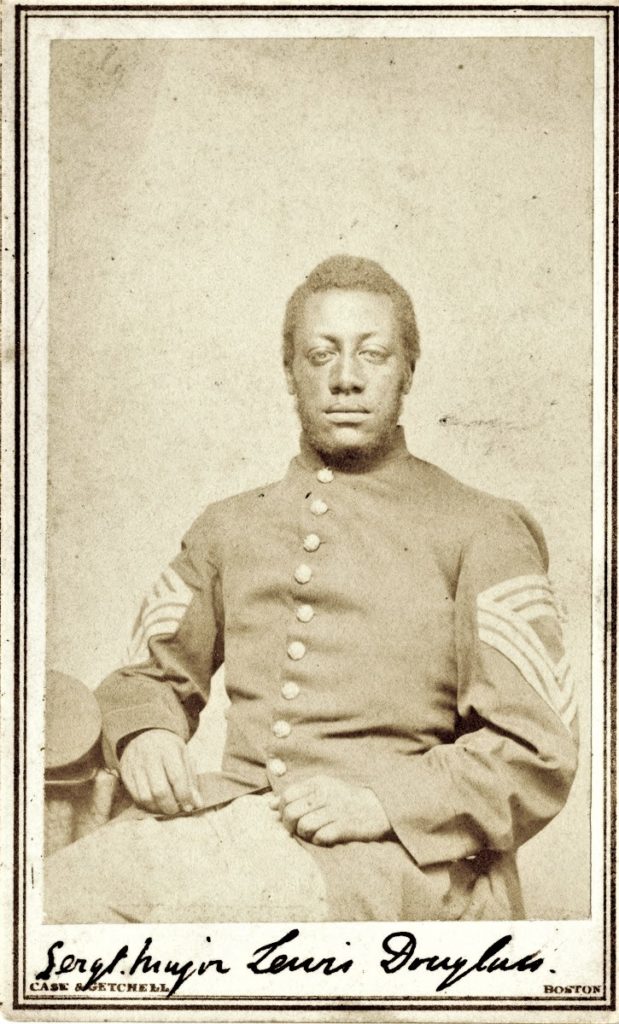

Also in 1869, Lewis Henry Douglass (1840-1908), the oldest son of Frederick Douglass (1818-1895), joined the Government Printing Office in Washington D.C., as the government’s first African American typesetter. In keeping with current standards for professional workers, he sent in his application to join the local branch of the ITU. This was the beginning of a protracted battle with union members arguing about whether a “colored printer” should be allowed to join their union.

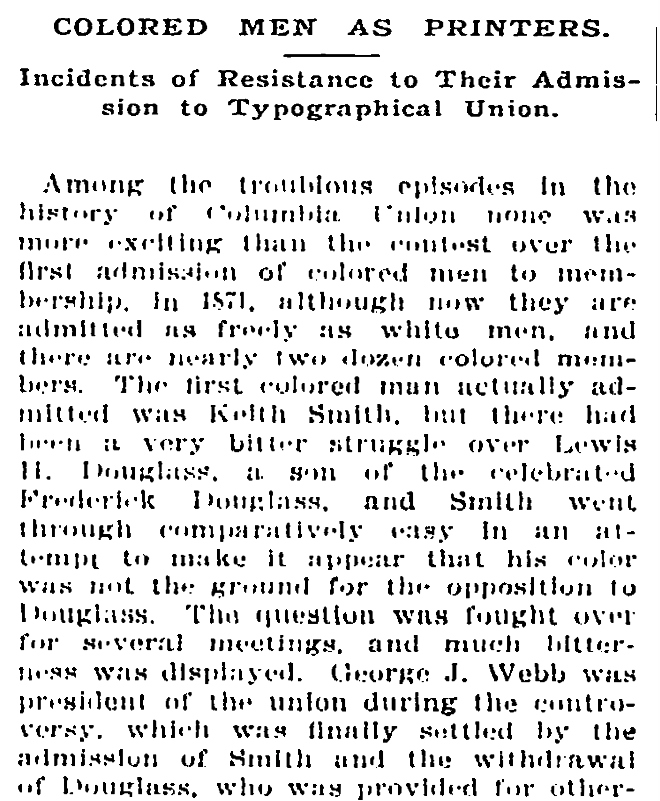

When it looked as though the Columbia chapter (Washington, D.C.) was going to accept Douglass’s application, a special national committee was appointed to study the “Negro question.” Only a few years after the Civil War, the topic was deemed too sensitive to resolve immediately and they left admittance of colored printers “to the discretion of Subordinate Unions.”

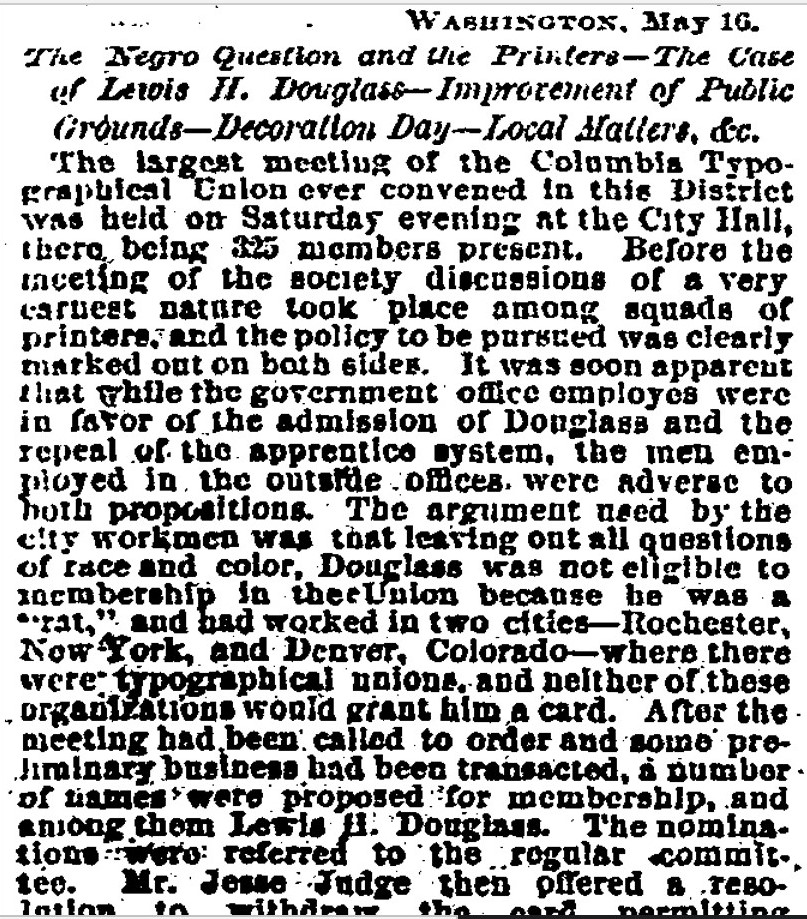

May 16, 1869, the question was finally raised at a meeting of the Washington D.C. chapter, the largest meeting ever convened, and there was massive confusion, both local and national disagreement voiced, proposals and then, counter proposals. Finally, the Union proceeded to vote on all the other candidates proposed for admission, leaving Douglass for last but just before that last name was proposed, a motion to adjourn was made and the meeting was over.

“It is said that Lewis H. Douglass, colored printer, was yesterday transferred from the case to a position as copy holder in the Government Printing Office. This action would seem to take the question of the admission of colored members to the Typographical union out of the control of such organizations, as copy holders are not required to be members of such Unions. But the issue having been raised, it will probably be pressed to a decision.”—Philadelphia Inquirer June 2, 1869

“The Negro Question and the Printers–The Case of Lewis H. Douglass” The Baltimore Sun, May 17 1869

Many letters were written to the President of the International Typographical Union, Douglass was called a ‘rat,’ someone who works outside the union, especially for lower wages. While still a teenager, he had apprenticed in Rochester, New York, as a typesetter for his father’s newspaper The North Star and after the Civil War, Lewis and his brother, Frederick Douglass, Jr. went to Denver where Henry O. Wagoner taught them all aspect of printing. Douglass never applied for union membership at either location and this was used against him, claiming he was trying to subvert the newly formed union.

“…acting in the interest of the minority, without any instructions from the Union—without the knowledge, advice, or consent of its membership—[someone] introduced a resolution, which was adopted by that body, censuring the Congressional Printer for employing L. H. Douglass, ‘an avowed rat’ calling upon Columbia Union to reject his application, and pledging the support of the National Union in such action.”

The Washington chapter wrote to leadership, calling this action “unjust, absurd, and unparalleled,”

The minority group that was against Black members threatened to eradicate the Columbia chapter and in response, the majority group that supported Douglass threatened to withdraw entirely, writing “If [the Union votes against Douglass] we shall … withdraw from the National Union and to organize a new National Typographical Society, which shall be founded on the principles of justice to all men, regardless of race or color.”

“That there are deep-seated prejudices against the colored race no one will deny; and these prejudices are so strong in many local unions that any attempt to disregard or override them will almost inevitably lead to anarchy and disintegration . . . and surely no one who has the welfare of the craft at heart will seriously contend that the union to thousands of white printers should be destroyed for the purpose of granting a barren honor of membership to a few Negroes.”–Printers’ Circular reprinted in Proceedings of the International Typographical Union of 1870 (Philadelphia, 1870), p. 140.

Two years went by and Douglass was still neither admitted to membership nor rejected. By this time, several other Black compositors had applied for union membership along with Douglass, including his brother Frederick Douglass Jr., William A. LaVelette, and Keith Smith. Eventually LaVelette withdrew his application. Keith Smith was admitted to the union in 1872(?), and Lewis Douglass is said to have been satisfied with another situation. No record of a vote on either Douglass men can be found. Lewis Douglass went on to help establish and publish The New National Era, a weekly newspaper aimed at Washington’s African American community.

Read more: Philip S. Foner and Ronald L. Lewis, editors. The Black Worker, Volume 1: The Black Worker to 1896. Temple University Press, 1978. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvn1tbr6. Accessed 17 July 2020.

See also: https://loc.gov/exhibits/civil-war-in-america/biographies/lewis-henry-douglass.html

In the Library Frederick Douglass Family Materials from the Walter O. Evans Collection April 22 – June 14, 2019 (National Gallery of Art, 2019)

African American Faces of the Civil War: An Album edited by Ronald S. Coddington (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012).