Although she would not today be allowed to join the Club of Odd Volumes or the Rowfant Club, Frances Mary Richardson Currer (1785-1861) was an esteemed bibliophile, described by T.F. Dibdin “at the head of all female collectors in Europe” and owner of the fourth largest library in England.

Although she would not today be allowed to join the Club of Odd Volumes or the Rowfant Club, Frances Mary Richardson Currer (1785-1861) was an esteemed bibliophile, described by T.F. Dibdin “at the head of all female collectors in Europe” and owner of the fourth largest library in England.

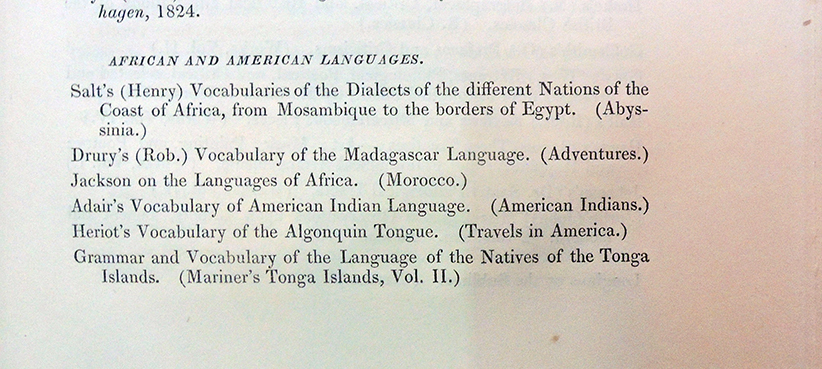

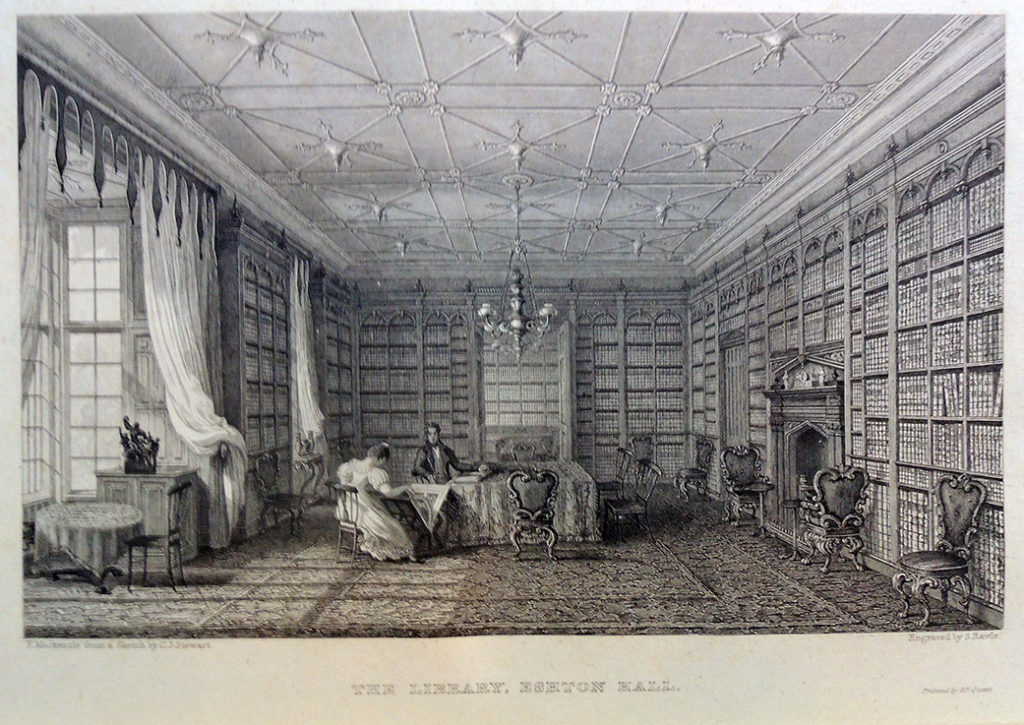

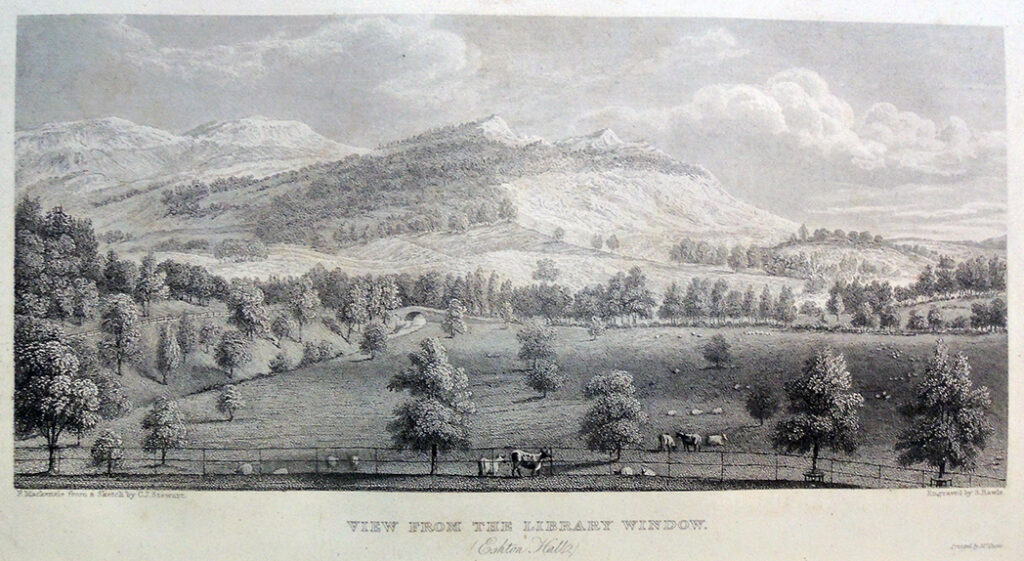

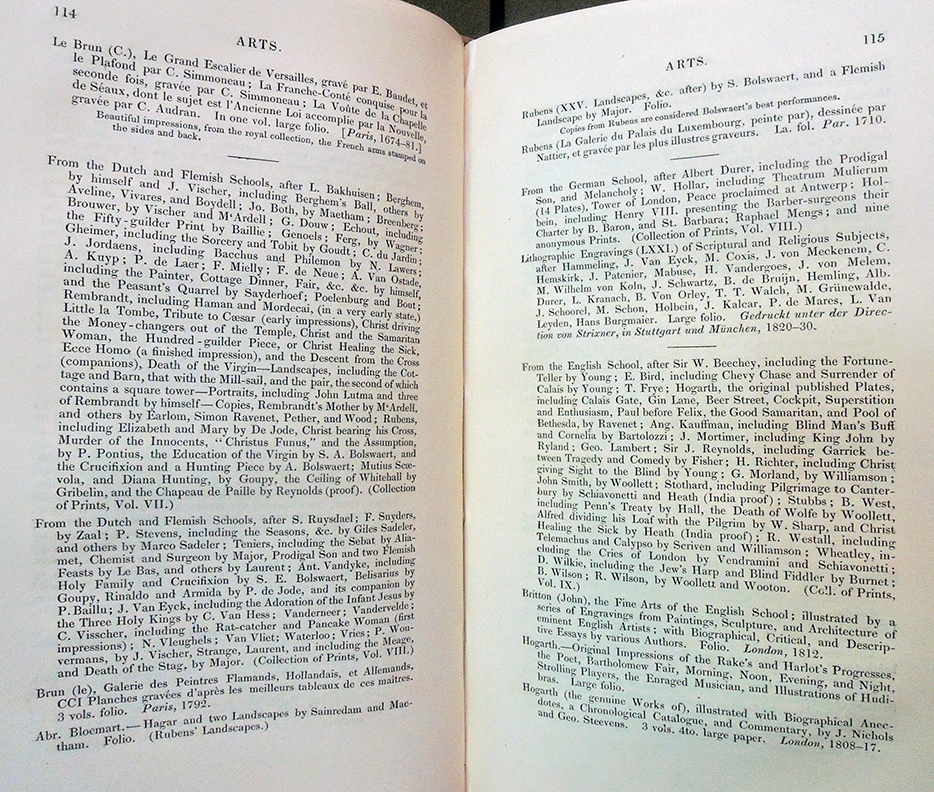

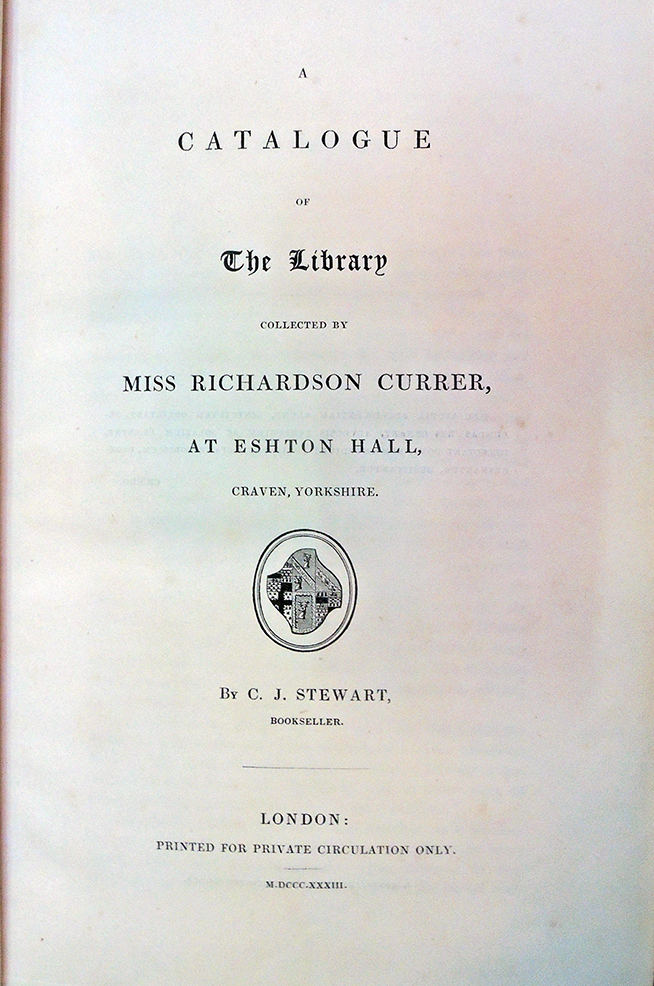

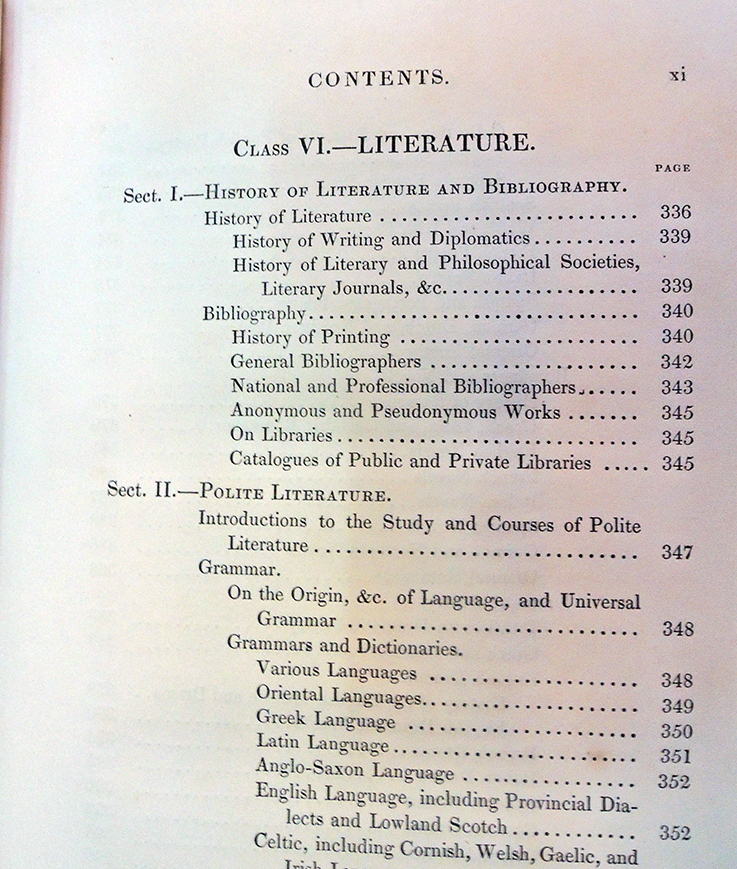

In 1820 Robert Triphook compiled A Catalogue of the Library of Miss Currer at Eshton Hall, in the Deanery of Craven and County of York, of which fifty copies were printed. In 1833 a second catalogue was prepared by C. J. Stewart, on a modified system devised by Hartwell Horne for the British Museum (although not used) in an edition of 100 copies. The Stewart catalogue has been acquired by the Graphic Arts Collection, which includes an excellent index to her library.

In 1820 Robert Triphook compiled A Catalogue of the Library of Miss Currer at Eshton Hall, in the Deanery of Craven and County of York, of which fifty copies were printed. In 1833 a second catalogue was prepared by C. J. Stewart, on a modified system devised by Hartwell Horne for the British Museum (although not used) in an edition of 100 copies. The Stewart catalogue has been acquired by the Graphic Arts Collection, which includes an excellent index to her library.

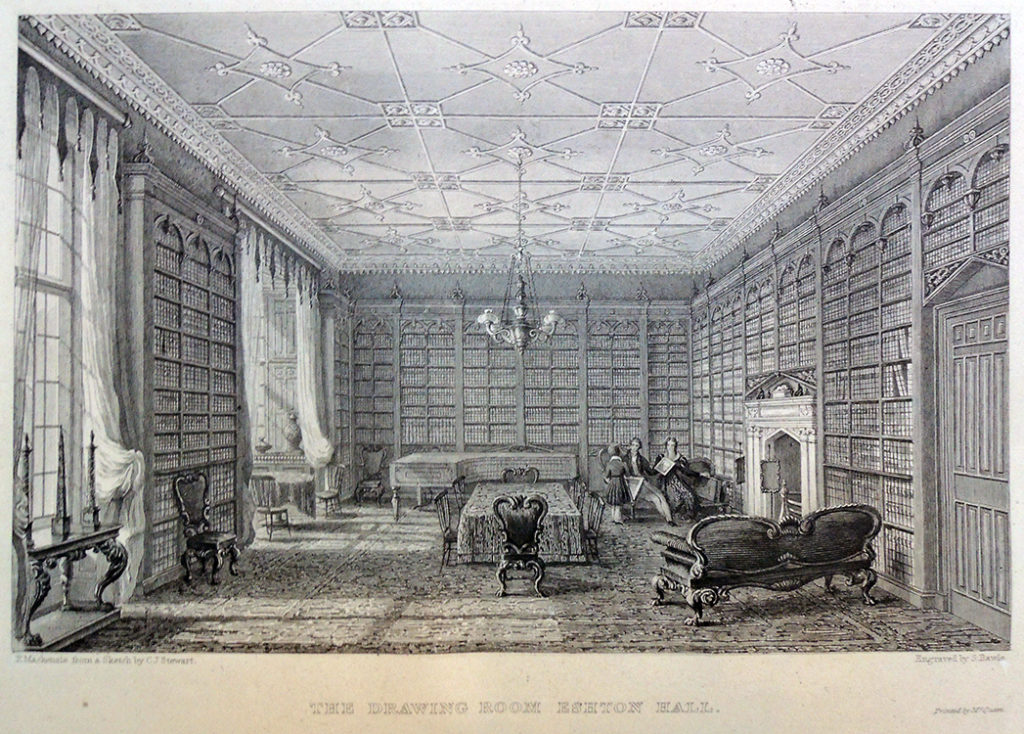

C.J. Stewart, A Catalogue of the Library Collected by Miss Richardson Currer, at Eshton Hall, Craven, Yorkshire (London: Printed for private circulation only [by J. Moyes], 1833). 4 plates by S. Rawle after Frederick Mackenzie (1787 or 1788-1854), printed by McQueen. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2020- in process

The plates are printed by the McQueen company, “a copperplate printing and publishing family firm, founded by William Benjamin McQueen [thanks to the British Museum biographies]. At 72 Newman Street, Rathbone Place from 1817-33, having probably been in business from the 1790s. The firm moved to purpose-built premises at 184 Tottenham Court Road 1833, where it remained for a century. In 1956, his descendant Philip McQueen joined Thomas Ross & Sons (q.v.) taking with him the McQueen firm’s stock of old plates and prints.”

Frances Mary Richardson Currer, photograph of a portrait by Masquerier, 1807.

Frances Mary Richardson Currer, photograph of a portrait by Masquerier, 1807.

“John James Masquerier (1778-1855) was an accomplished portraitist who enjoyed a wide practice among the intellectual and artistic communities at the turn of the nineteenth century. Born in London to Huguenot parents, Masquerier returned with his family to Paris in 1789. He enrolled at the Académie Royale under the supervision of the director François André Vincent. Having witnessed many of the bloody events of the French Revolution, Masquerier escaped back to London in 1792. He entered the Royal Academy Schools, exhibiting for the first time in 1794, after which his services as a portrait painter were much in demand. Masquerier returned to Paris in 1800, where he was granted access to make drawings of Napoleon from life.”—National Portrait Gallery, UK

Currer is a fascinating bibliophile. Here is additional information quoting from the DNB: https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/6951

Currer is a fascinating bibliophile. Here is additional information quoting from the DNB: https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/6951

Currer, Frances Mary Richardson (1785–1861), book collector, was born on 3 March 1785 at Eshton Hall, near Gargrave, in the West Riding of Yorkshire. She was the posthumous daughter and sole heir of the Revd Henry Richardson (1758–1784) who, shortly before his death, took the name of Currer on succeeding to the estates of Sarah Currer. Her mother was Margaret Clive Wilson, the only surviving child and heir of Matthew Wilson of Eshton Hall; she was a niece of Clive of India.

‘She is’, wrote Mrs. Dorothy Richardson in 1815: in possession of both the Richardson and Currer estates and inherits all the taste of the former family, having collected a very large and valuable library, and also possessing a fine collection of prints, shells, and fossils, in addition to what were collected by her great grandfather and great-uncle. F. Dibdin considered that Currer’s collection placed her ‘at the head of all female collectors in Europe’ (Reminiscences, 2.949) and that her country house library was, in its day, surpassed only by those of Earl Spencer, the duke of Devonshire, and the duke of Buckingham. Seymour De Ricci wrote that she was ‘England’s earliest female bibliophile’ (De Ricci, 141).

Dibdin relates that the library had substantial holdings in natural science, topography, antiquities, and history, together with a collection of the classics. There were rarities, some early printed books, a collection of Bibles, and a fine gathering of illustrated books. Although ‘collected with a view to utility … The books individually are in the finest condition, and not a few of them in the richest and most tasteful bindings’ (Stewart). The manuscripts included the correspondence (1523–4) of Lord Dacre, warden of the Anglo-Scottish marches, the Richardson correspondence, and the Hopkinson papers. John Hopkinson (1610–1680) was secretary to Dugdale during his Yorkshire visitation. Dibdin first estimated the number of volumes at 15,000 and, later, 18,000. In 1852, Sir J. B. Burke put the number at 20,000 (Burke, 1.127).

- Lister, ‘The lady of Eshton Hall’, Antiquarian Book Monthly Review, 12 (1985), 382–9

- F. Dibdin, Reminiscences of a literary life, 2 vols. (1836), 949–57

- Myers and M. Harris, eds., Antiquaries, book collectors and the circles of learning (1996), 112 n. 80