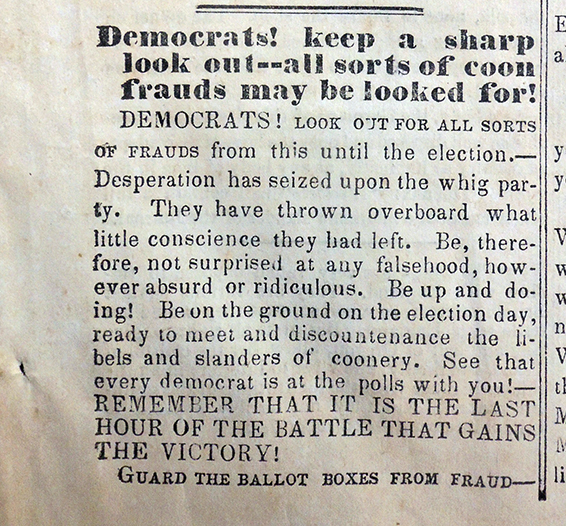

Politicians frequently use animals to symbolize their party, currently a donkey for the Democrats and an elephant for Republicans. Beginning in the 1840s, the American Whig party took the raccoon as its symbol, along with its associations with independent frontiersmen and their raccoon-skin caps. Nineteenth-century Democrats used the rooster.

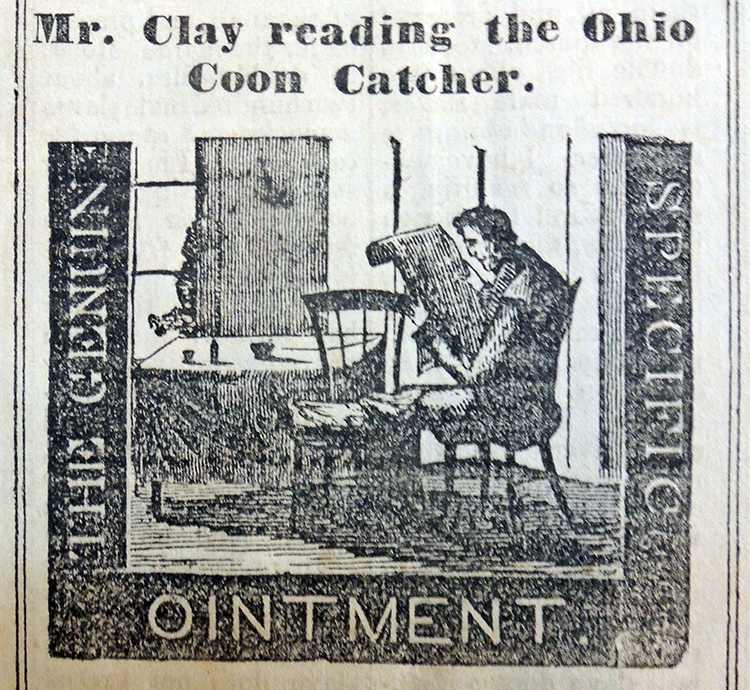

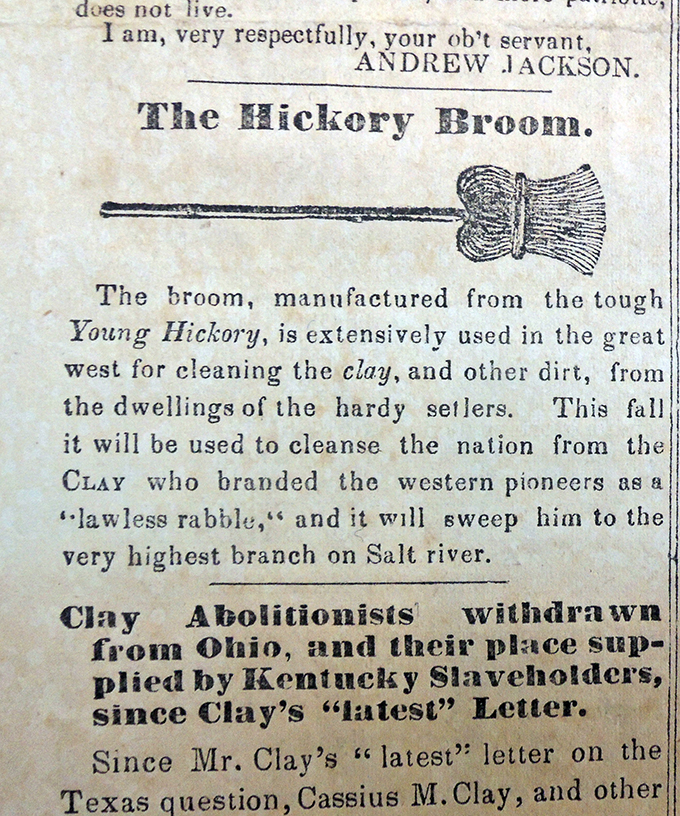

During the presidential election of 1844 between Democrat James K. Polk (1795-1849) and Whig Henry Clay (1777-1852) these two symbols were used effectively in rude and offensive caricatures of the other party. According to the Dictionary of Etymology the abbreviation for raccoon was already in use as a vulgar reference to African Americans, giving added weight to the ridicule loaded into anti-Whig texts and images.

“The now-insulting U.S. meaning “black person” was in use by 1837, said to be from barracoon (by 1837), from Portuguese barraca “slave depot, pen or rough enclosure for black slaves in transit in West Africa, Brazil, Cuba.” If so, no doubt this was boosted by the enormously popular blackface minstrel act Zip Coon (George Washington Dixon) which debuted in New York City in 1834. But it is perhaps older (one of the lead characters in the 1767 colonial comic opera “The Disappointment” is a black man named Raccoon).”– https://www.etymonline.com/word/coon

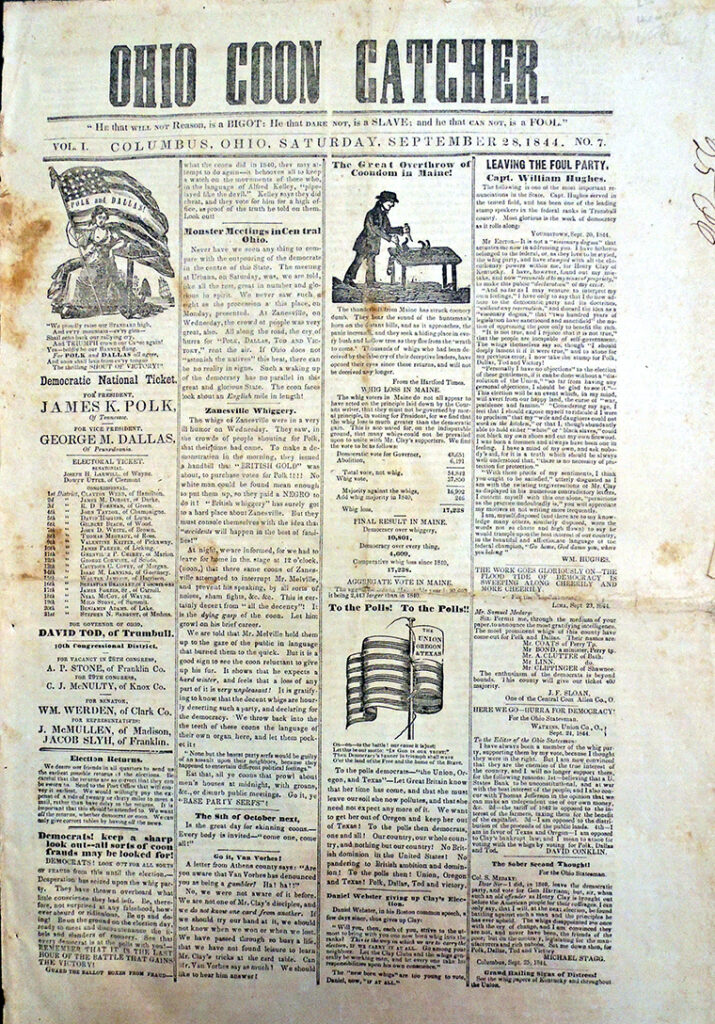

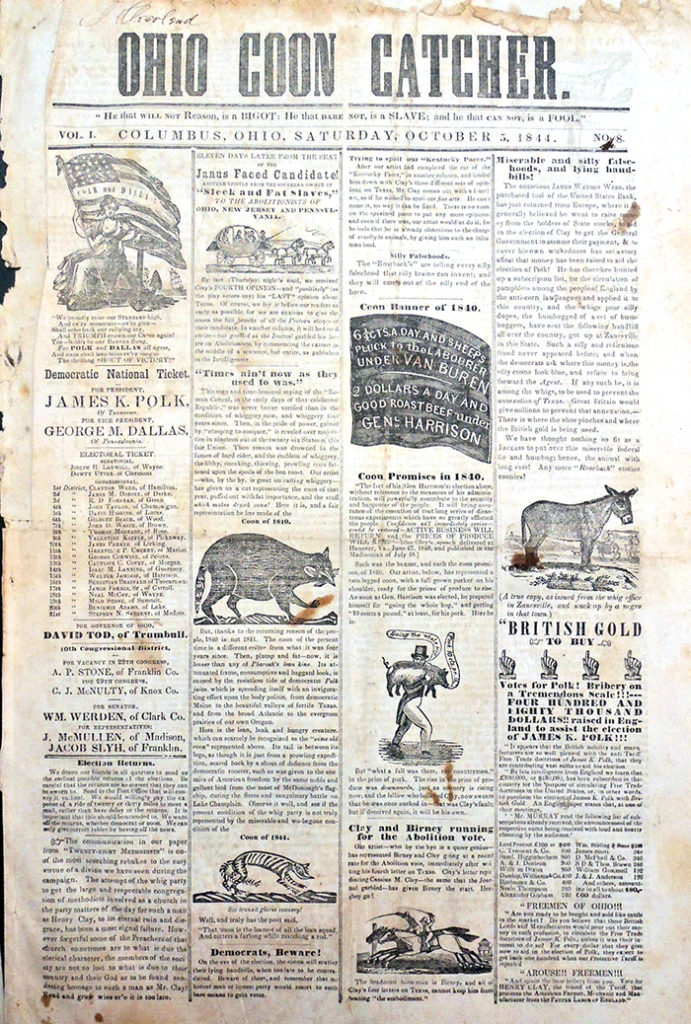

One of the chief issues in the 1844 election was slavery and the annexation of the Republic of Texas. This can be seen in the use of the raccoon caricatures in the anti-Whig newspaper The Ohio Coon Catcher, published by the Democrats in the pro-Whig state of Ohio. There were several other similar newspapers on either side.

The Graphic Arts Collection has an incomplete run of The Ohio Coon Catcher, which was published between August and November 1844, during the first American election held in November. A complete digital run has been posted by the Ohio Memory project https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p16007coll29. The paper was the project of Samuel Medary (1801-1864) the editor and publisher of the Ohio Statesman, as well as head of the Ohio delegation to the democratic National Convention. In both text and image, it promoted Polk’s candidacy with news items, political opinion, testimonials of reformed Whigs, poems, and cartoons.

In the national popular vote, Polk beat Clay by fewer than 40,000 votes, a margin of 1.4%.

See also: W. Miles, The people’s voice: An annotated bibliography of American presidential campaign newspapers, 1828-1984. Westport, CT: Greenwood press, 1987.