End of the Parade, Coatesville, Pa., 1920. Tempera and pencil. The collection of Deborah and Ed Shein.

End of the Parade, Coatesville, Pa., 1920. Tempera and pencil. The collection of Deborah and Ed Shein.

One hundred years ago at the Charles Daniel Gallery, the premier New York City venue for American modernism, Charles Demuth (1883-1935) exhibited his “Arrangements of the American Landscape Forms,” which included twelve tempera and gouache paintings: Pennsylvania now called In the Providence, After Sir Christopher Wren, New England, Waiting, Pennsylvania, The Merry-Go-Round, For W. Carlos W. now called Machinery, New England, The End of the Parade—Coatesville, Pa., New England now called Lancaster, Chimnies [sic], Ventilators or Whatever, now called Masts, and New England.

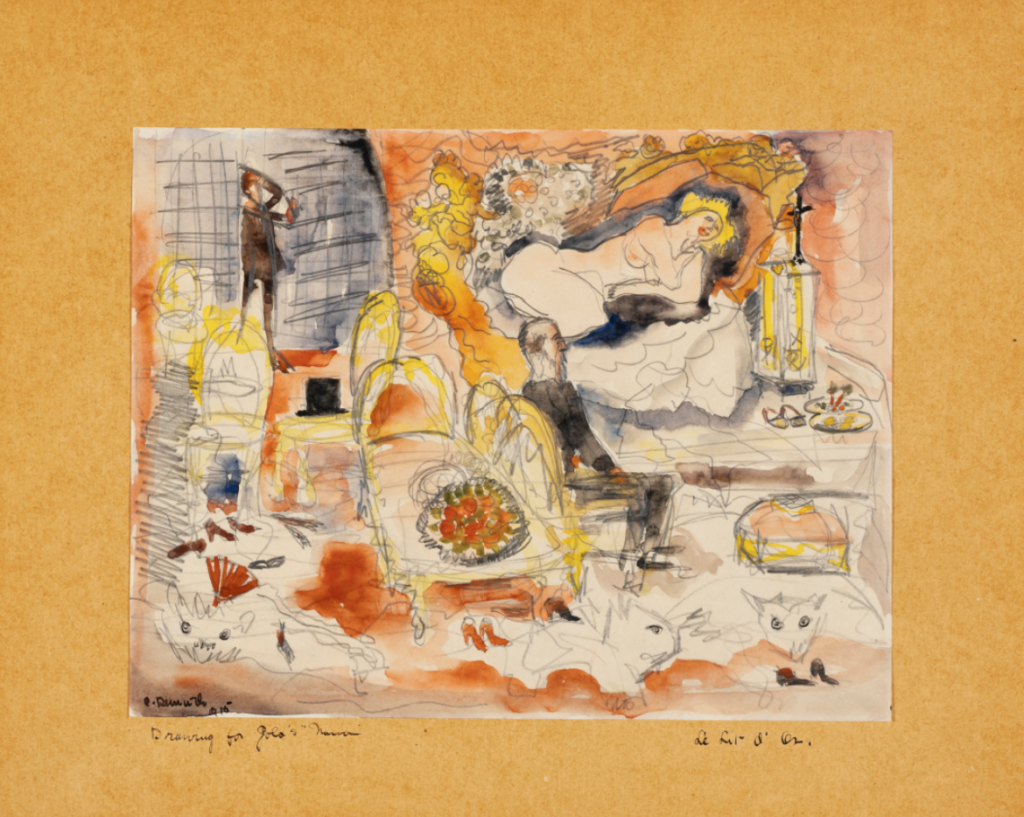

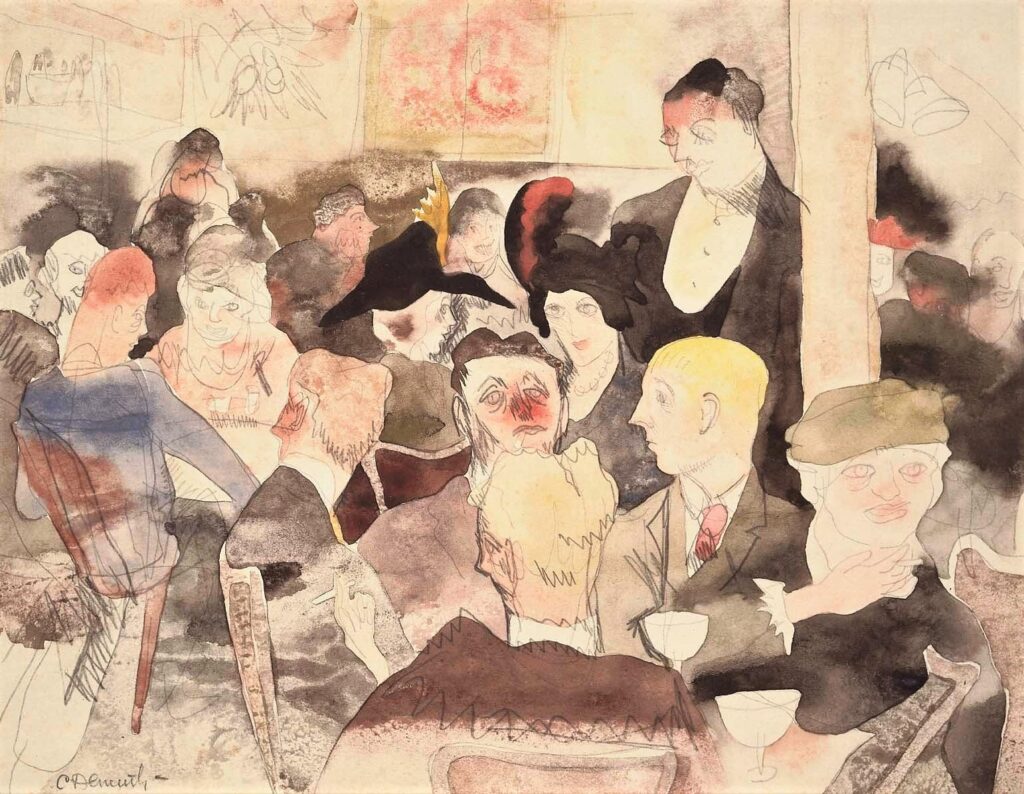

Charles Demuth self-portrait with Marcel Duchamp entitled The Purple Pup, about 1918. Watercolor over graphite. Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

Charles Demuth self-portrait with Marcel Duchamp entitled The Purple Pup, about 1918. Watercolor over graphite. Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

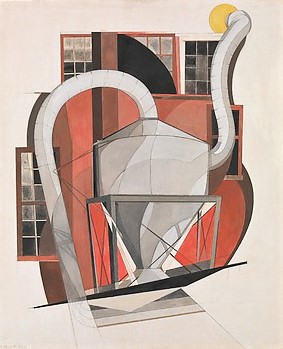

With this leap forward, Demuth replaced traditional American landscape painting with industrial architecture, as seen in his hometown of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The reference to William Carlos William (1883-1963), Demuth’s friend since their college days, with the title of Machinery was an inside joke since Demuth knew Williams would object to the perceived teapot imagery, rather than letting the forms and colors speak for themselves.

Machinery, 1920. Tempera and pencil. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Alfred Stieglitz Collection.

Machinery, 1920. Tempera and pencil. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Alfred Stieglitz Collection.

Williams complimented his friend by purchasing End of the Parade [above], which in turn inspired his poem: “The End of the Parade / The sentence undulates, / raising no song; / it is too old, the / words of it are falling / apart. Only percussion / notes continue / with weakening emphasis what was once / all honeyed sounds / full of sweet breath.” –Collected Poems, 1921–1931 (Objectivist Press, 1934. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015066064604)

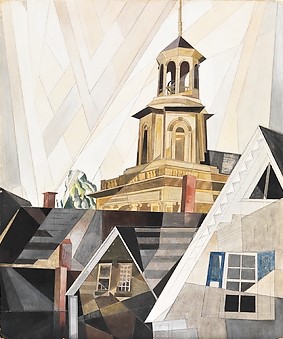

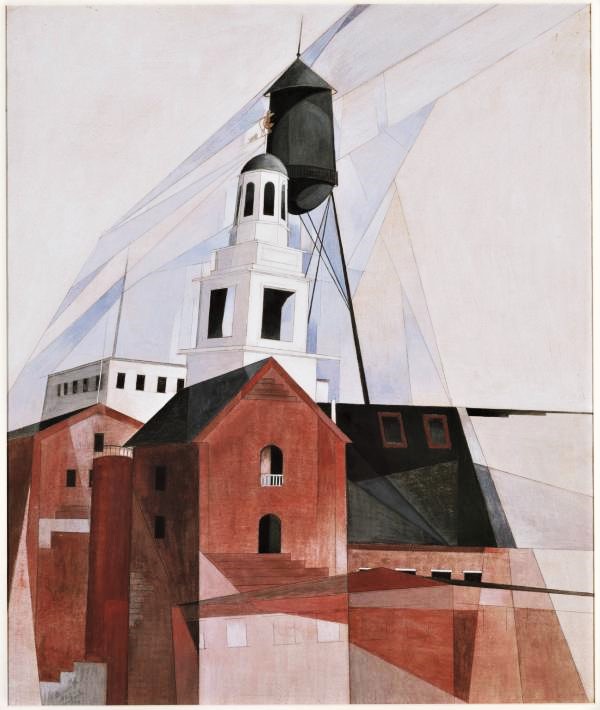

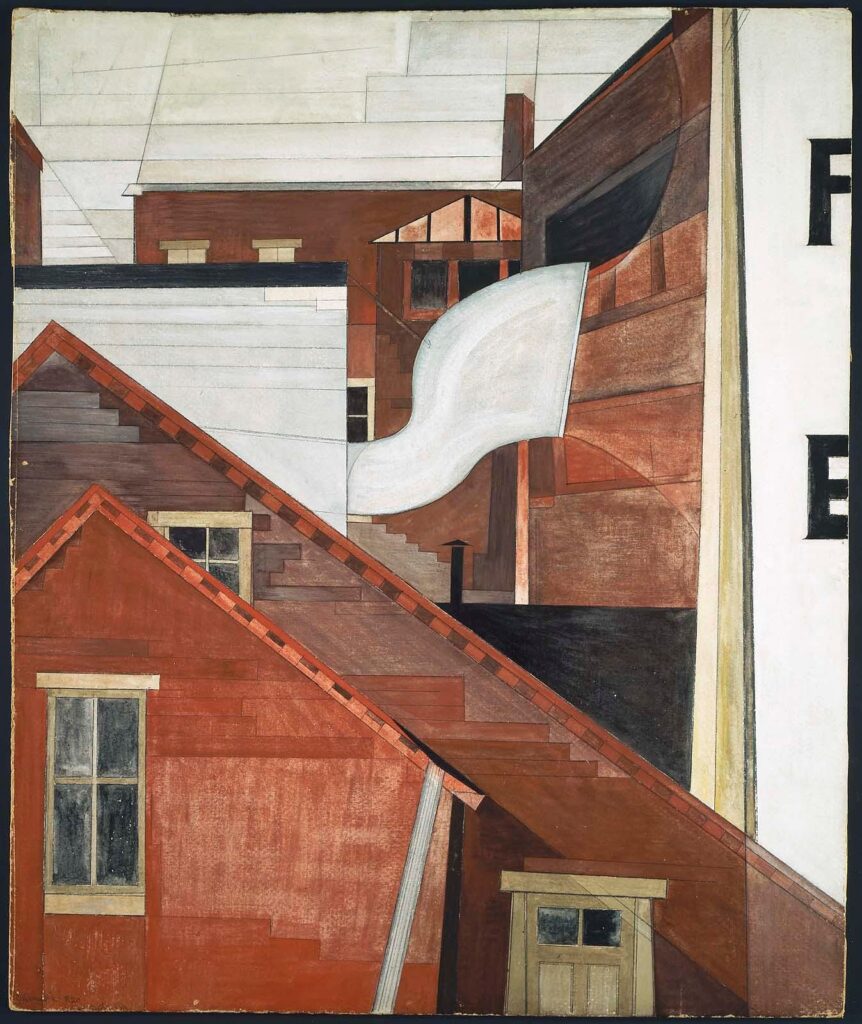

Ohio collector Ferdinand Howald snapped up The Tower [above], which was later donated to The Columbus Museum of Art (not to be confused with After Sir Christopher Wren, given to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, by Scofield Thayer). Walter Arensberg bought one of several works listed as New England, which he later gave to the Philadelphia Museum of Art under the title Lancaster.

Ohio collector Ferdinand Howald snapped up The Tower [above], which was later donated to The Columbus Museum of Art (not to be confused with After Sir Christopher Wren, given to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, by Scofield Thayer). Walter Arensberg bought one of several works listed as New England, which he later gave to the Philadelphia Museum of Art under the title Lancaster.

After Sir Christopher Wren, 1920. Watercolor and gouache. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Scofield Thayer.

After Sir Christopher Wren, 1920. Watercolor and gouache. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Scofield Thayer.

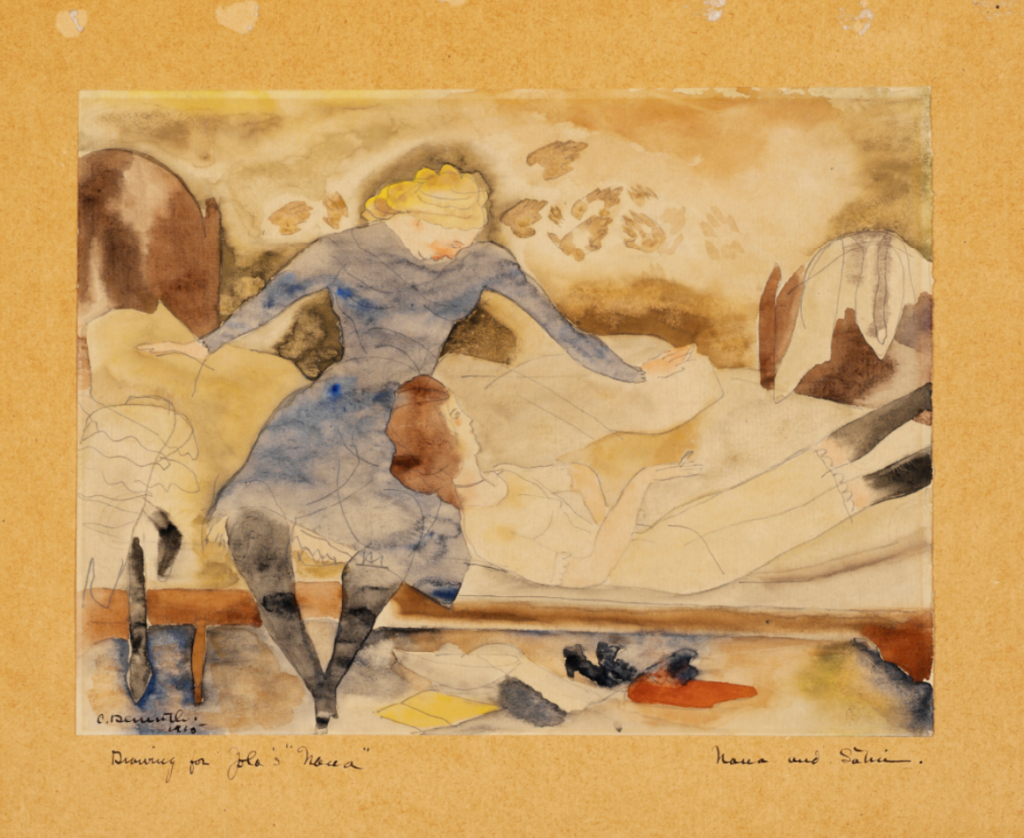

In the backroom, Charles Daniel continued (as he had since 1916) to show trusted friends Demuth’s watercolors after Émile Zola’s 1880 novel Nana. The critic Henry McBride wrote “Mr. Daniel . . . showed us all, surreptitiously, some figure drawings. They were not precisely shocking, but one or two of the drawings illustrated points in Zola’s Nana and just before the war we were still sufficiently Victorian to shudder at the thought of exposing pictures of reprehensible Nana on the walls of the public gallery.” –(“Water Colors by Charles Demuth,” Creative Arts September 1929).

Another critic, Forbes Watson noted that “whoever enjoys a whimsical imagination will revel in Mr. Demuth’s illustrations of Zola’s Nana… The man who obtains this group of illustrations will be a lucky man.”—(“At the Galleries,” Arts and Decoration, January 1921). One year later, Albert Barnes purchased eight of the twelve Nana watercolors [three seen here] for what is now the Barnes Foundation, where a total of forty-four Demuth paintings hang.

Demuth’s now lost “Merry-Go-Round” is presumed to be inspired by Richard Oswald’s 1920 silent film The Merry-Go-Round (Der Reigen – Ein Werdegang), with a story similar to Nana and Frank Wedekind’s Lulu plays, also illustrated by Demuth.

Demuth was introduced to The Daniel Gallery by Daniel’s protégé, another gay modernist painter Preston Dickinson (1891–1930), also in Paris during 1910, renting a room on the same street as Demuth. Together with Thomas Hart Benton, Louis Bouché, and Marguerite Thompson (Zorach), the Americans returned to New York where they all found a welcome home for their work with The Daniel Gallery at 2 West 47th Street (Katherine Dreier rented rooms across 5th Avenue and shared exhibitions with Daniel). Daniel celebrated his good fortune by arranging eight one-person shows for the young Demuth and included his paintings in thirty-one group exhibitions, more than any other artist.

Lancaster, 1920. Tempera and gouache. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Arensberg Collection.

Lancaster, 1920. Tempera and gouache. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Arensberg Collection.

Why go further? One might conceivably rectify the rhythm, study all out and arrive at the perfection of a tiger lily or a china doorknob. One might lift all out of the ruck, be a worthy successor to—the man in the moon. Instead of breaking the back of a willing phrase why not try to follow the wheel through—approach death at a walk, take in all the scenery. There’s as much reason one way as the other and then—one never knows—perhaps we’ll bring back Eurydice—this time! –William Carlos Williams, Kora in Hell: Improvisations (1920. Section 2).

In the Province, 1920. Gouache and pencil. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

In the Province, 1920. Gouache and pencil. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.