As a young boy, Henry Thomas de la Beche (née Henry Beach, 1796-1855) inherited a sugar plantation from his father. Located in Clarendon, Jamaica, Halse Hall was managed primarily by enslaved Jamaicans and provided de la Beche, living in England and later Wales, with a substantial income. It wasn’t until December 1823 that he first traveled to Jamaica, spending one year on the island to conduct a survey and learn about the Jamaican men and women who ran his plantation. Back home in 1825, he published Notes on the Present Condition of Negroes in Jamaica. The introductory notes begin:

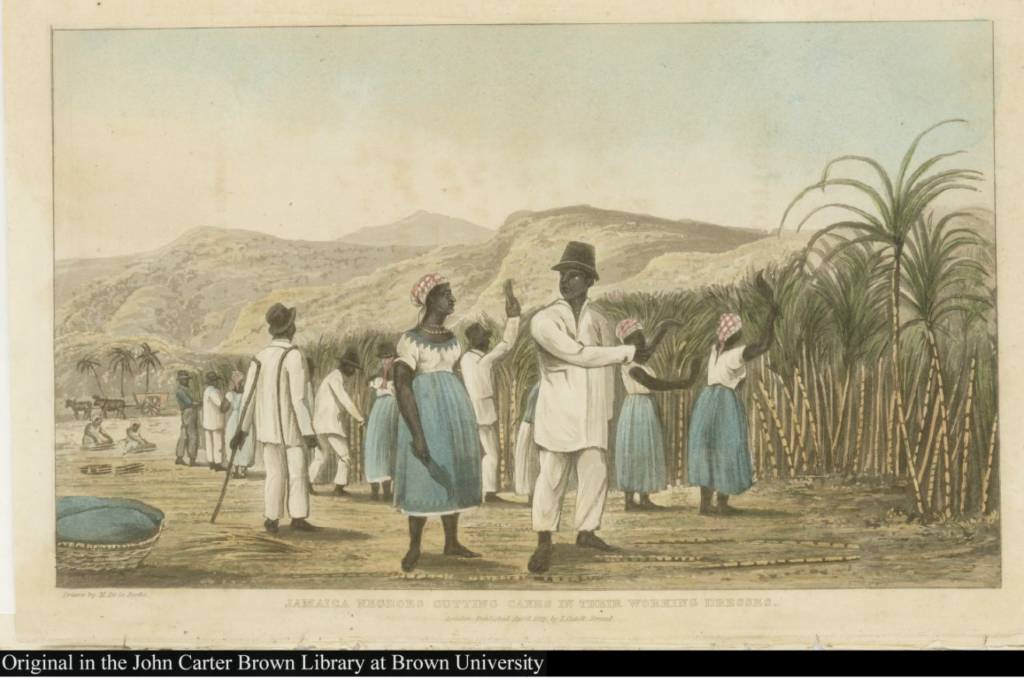

“Jamaica Negroes Cutting Canes in their Working Dresses,” lithographic frontispiece in Henry T. De La Beche, Notes on the Present Condition of the Negroes in Jamaica (London: Printed for T. Cadell, in the Strand Source, 1825). Original in the John Carter Brown Library

De la Beche wrote “that I am no friend to slavery in any shape, or under any modification,” but never fully denounced the practice at his own estate.

“At the time of De la Beche’s visit Halse Hall owned 207 mainly ‘creole’ slaves, mostly born on the plantation. They are woken at five o’clock by the bell of the ‘head driver’, and start work at daybreak. Breakfast is at nine, and dinner at half past twelve, though the negroes skip the meal and spend their time tending their ‘provision grounds’. Work resumes and continues without a break until half an hour after sunset, after which the slaves can ‘spend the evening as they think proper’. De la Beche is proud that his drivers don’t carry whips, as they do on other plantations, and punishments are carried out by their overseers. The head driver at Halse Hill, we’re assured, ‘is an intelligent, human and steady man’. Failure to complete digging the allotted number of cane-holes leads to withdrawal of rum and sugar rations. ‘Weakly adults’ and children perform lighter duties. At crop time – four months of the year, and apparently a ‘merry time’ for the slaves – the workforce is split into two shifts, and work continues day and night.”– https://gwallter.com/history/henry-de-la-beche-defends-slavery.html

It was around this time that de la Beche had a medallion produced by engraver Tomasso Saulini (1793-1864), which could be given to his workers in recognition of “Good Conduct.” One side carried his own profile and the other the words “Reward for Good Conduct. Halse Hall, Jamaica.” Long after slavery had been abolished in Jamaica (1833) de la Beche had a second, larger medal produced by the engraver William Wyon (1795-1851), again with his profile on one side and a Jamaican landscape on the other along with “Reward for Good Conduct. Halse Hall, Jamaica.”

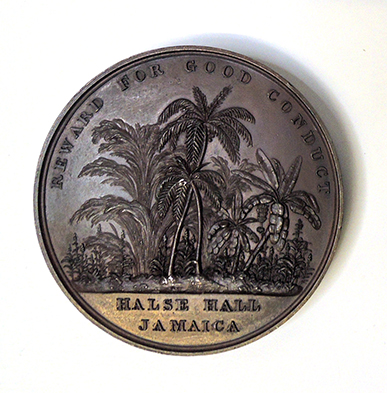

Tomasso Saulini (1793-1864), Award for Good Conduct medal, ca. 1824. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2021- in process

William Wyon (1795-1851), Award for Good Conduct medal, 1841. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2021- in process.

For a more complete record of Halse Hall see: Gwallter, a blog and more from Swansea by Andrew Green / blogfan a mwy o Abertawe gan Andrew Green.