Lit from the front

Lit from the front

Lit from the back

Lit from the back

Verso showing the tissue paper backing

Verso showing the tissue paper backing

There is little information on Mr. Browne of Browne’s Transparencies. The British Museum’s print described as “Scene in ecclesiastical ruins at night, with people gathered in the left foreground cooking over an open fire, and a couple walking further off,” transparency with hand-colouring recto and verso is probably also one of Browne’s Transparencies, although the label is torn.

There is little information on Mr. Browne of Browne’s Transparencies. The British Museum’s print described as “Scene in ecclesiastical ruins at night, with people gathered in the left foreground cooking over an open fire, and a couple walking further off,” transparency with hand-colouring recto and verso is probably also one of Browne’s Transparencies, although the label is torn.

Two comments about transparency prints that mention Browne were published in the July 8, 1882 issue of Notes and Queries. “These curiosities were more common some forty years ago [1842] than is generally supposed. Many of them were lithographs coloured by hand, and with one or more plates behind so perforated that when held up to the light the scene was completely changed. The first I remember (and still have) cost four or five shillings, and was the second of “G.W.’s Dioramic Views,” representing “A Village destroyed by an Avalanche,” and was published by Reeves & Sons, Cheapside, and W. Morgan, 64, Hatton Garden.”

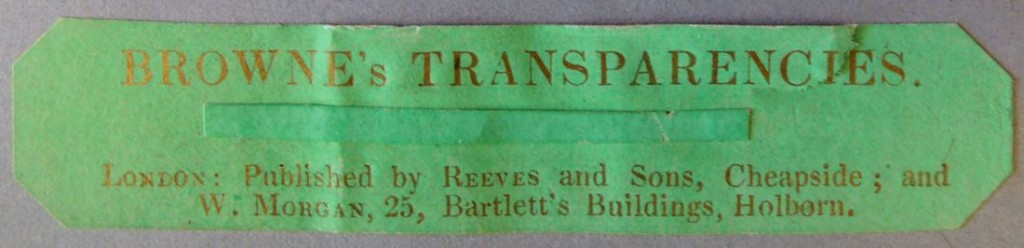

“. . . One “G. T. B.” also issued a series of “Transparencies,” of which I have only No. 5; and “Browne’s Transparencies,” of which I have only one, “Ruins by Moonlight,” were also issued by Reeves & Sons, Cheapside, and Morgan, 64, Hatton Garden. All these are on cardboard “mounts,” and show best by artificial light. I have never seen any adapted for the lower panes of windows, but I have one of “A Smugglers’ Cave,” apparently that referred to by P. P., and the shape is “unsuitable for a window pane.” — Estb. Birmingham.

The second note followed: “These certainly were in existence about the year 1837, and I am inclined to believe that they were printed and published by a firm in Cheapside. They were artistically printed in colours, and by holding them before a strong light the subjects, which were varnished and pasted on at the back, became visible. The fire, for instance, was seen in the bandits’ cave; the gipsies [sic] appeared boiling their kettle in the ruins of Netley Abbey; the empty chairs in the continental cathedral were filled with occupants; Vesuvius sent forth its volumes of flame; and Napoleon, instead of standing alone at St. Helena, reviewed his Old Guard. The last-named transparent print was entitled “Napoleon powerless and Napoleon powerful.” They must at the present time be very scarce. – John Pickford, M.A. Newboume Rectory, Woodbridge.”

See also Edward Orme, An essay on transparent prints, and on transparencies in general (London: Printed for, and sold by, the author, 1807). Graphic Arts Collection (GA) Oversize Rowlandson 8415q

The shop selling Browne’s Transparencies was W.J. Reeves & Son or Reeves & Sons (1819-1890). According to the Index to British Artists’ Suppliers, “By 1819 William John Reeves was 65 and the business became W.J. Reeves & Son, when his son, James Reeves (1794-1868), was taken into partnership. Subsequently in 1827 another son, Henry Reeves (1804-1877), joined the business. Following William John’s death in 1827, the business became Reeves & Sons . . . James Reeves retired in 1847 and in the following year two of his nephews, the brothers Henry Bowles Wild (1825-82) and Charles Kemp Wild (1832-1912), were taken into the business (Goodwin 1966 p.36); they were both listed as artists’ colourmen in the 1851 census, ages 26 and 18, residing with their father, Henry Wild, a wine merchant at 98 St Martin’s Lane. On the retirement of Henry Reeves in 1866, control moved to the Wild family who made the decision to remove manufacturing from Cheapside to a much larger site in Dalston, where they built a four-storey factory.”