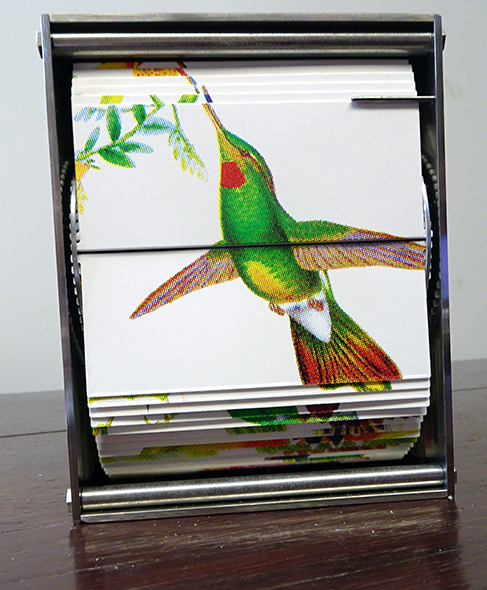

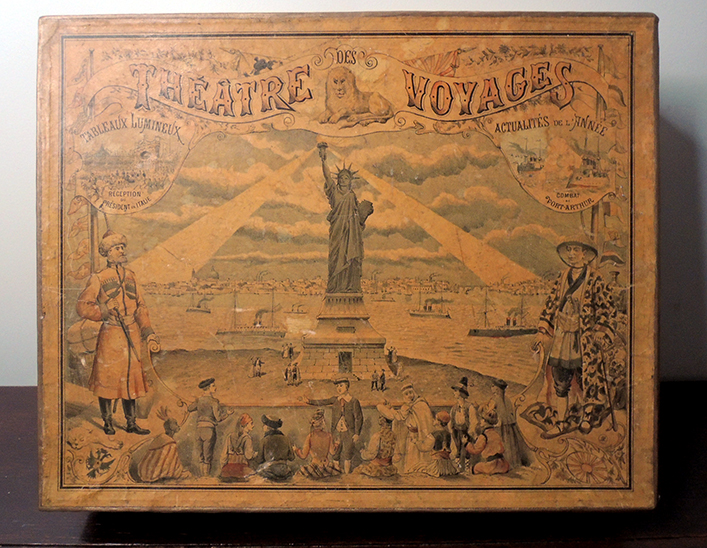

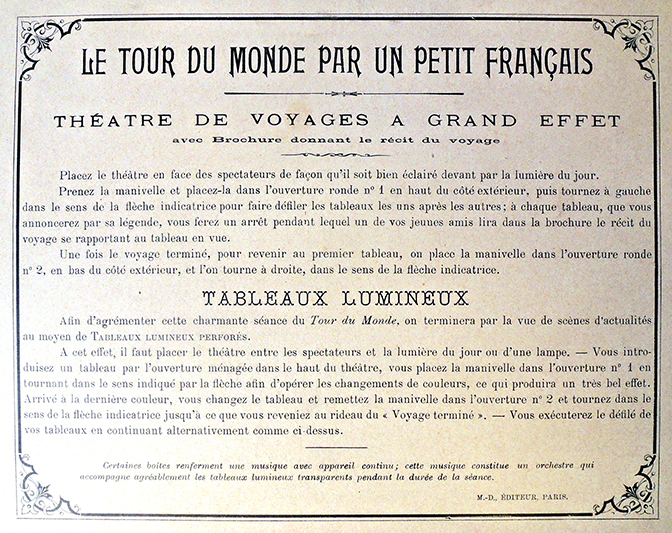

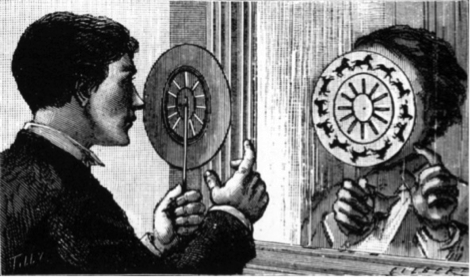

Like the 18th-century metamorphosis books, or the 19th-century Mutoscopes, or Thomas Edison’s 19/20th-century Kinetoscopes, the newly acquired “Ornithology L” by J.C. Fontanive is a sequence of images viewed in rapid succession. It will join our Zoetropes and Phenakistoscopes and other optical devices bringing our history of moving images delightfully into the 21st century.

Ornithology P from J. C. Fontanive on Vimeo.

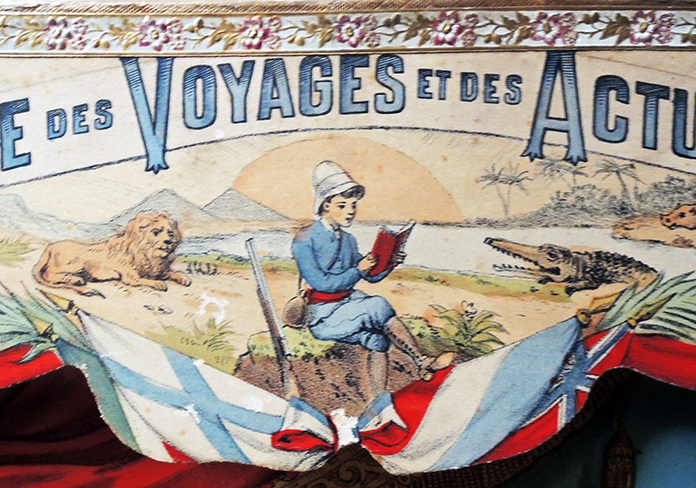

“Juan Fontanive’s work reflects a duel interest in the rhythmic pulse of the natural world and the modern era’s invention of the moving image. While studying Literature and Textual Studies as an undergraduate at Syracuse University, Fontanive began experimenting with 16mm film, combining narrative and image. While pursuing a Masters Degree at the Royal Academy in London, Fontanive began creating hand-tooled mechanized flip books Fontanive has described as, “films without light.” Each compact aluminum cube is machined to flip through 72 double-sided screen-prints depicting birds, moths, and butterflies that are sourced from 18th and 19th century natural history illustrations, or collaged together; or, in the instance of his moth series, Otherlight, are original hand-drawn images. The perpetual movement through the images create the illusion of flight while at the same time, flipping through the images at half the rate of film, also gives the viewer a long gaze at the detailed illustrations.” https://conduitgallery.com/artists/juan-fontanive

For more of the artist’s work see: http://www.juanfontanive.com/

See Edison’s birds!!:

Ornithology I from J. C. Fontanive on Vimeo.