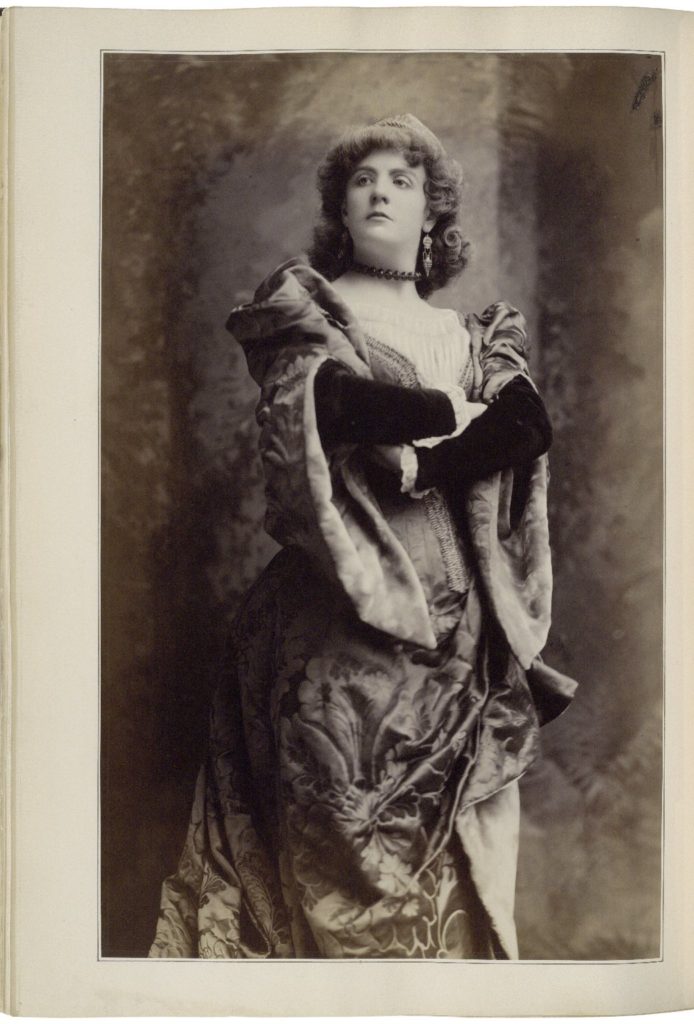

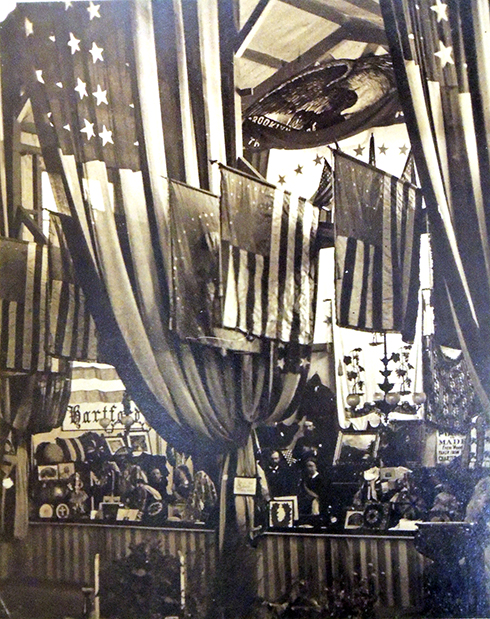

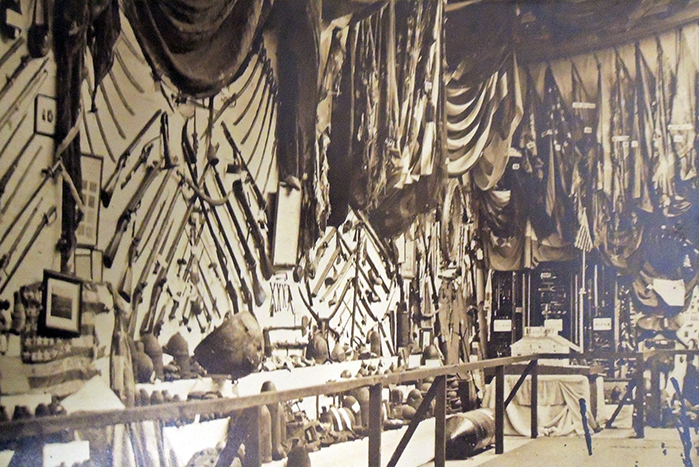

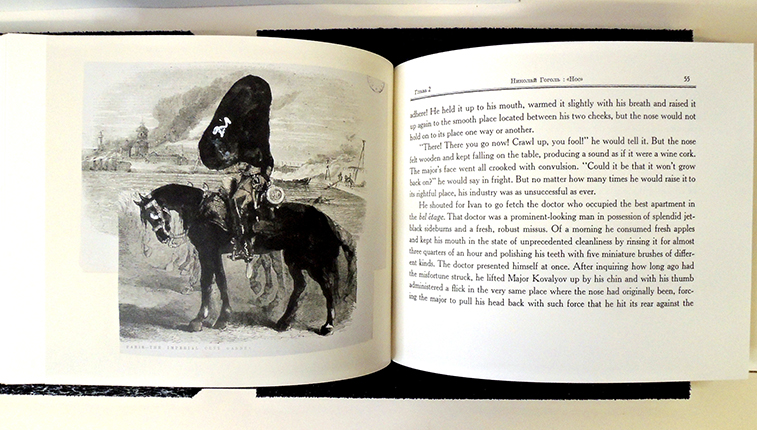

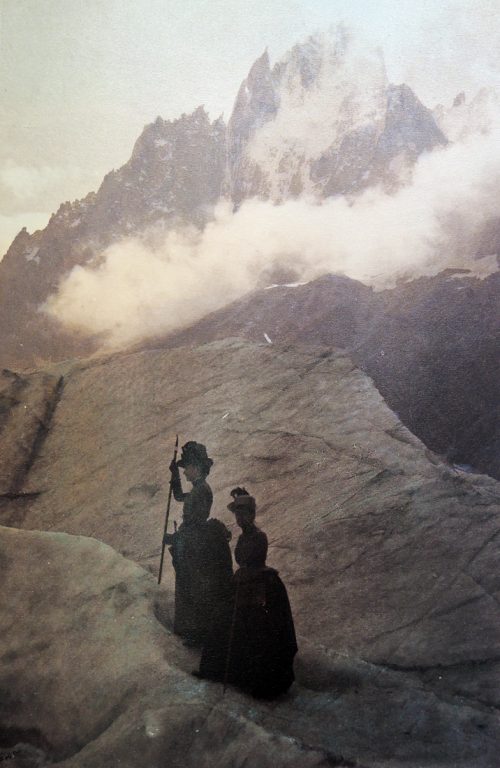

John Gast, “A New Jersey Landscape,” Photo-Stigmograph in The Philadelphia Photographer August 6, 1887. Graphic Arts Collection

John Gast, “A New Jersey Landscape,” Photo-Stigmograph in The Philadelphia Photographer August 6, 1887. Graphic Arts Collection

John Gast (1842–1896) was brought to the United States from Berlin at the age of six and went on to forged a substantial career as a painter, lithographer, and photomechanical printer. He is primarily remembered for one oil painting, “American Progress” (1872) but more importantly, filed seven new printing patents and was instrumental in establishing several businesses including the Gast Banknote and Lithograph Company (St. Louis); The New York Daily Graphic newspaper; Gast and Company Lithographers (Brooklyn), and the Photochrome Company (also called the Heliochrome Company), which was later purchased in part by Alfred Stieglitz’s father to give his son a stable job.

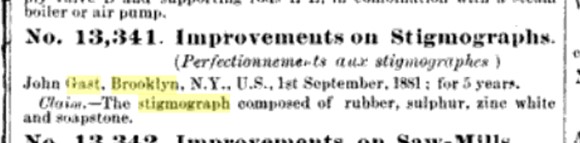

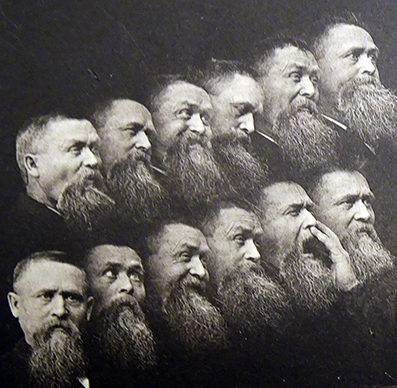

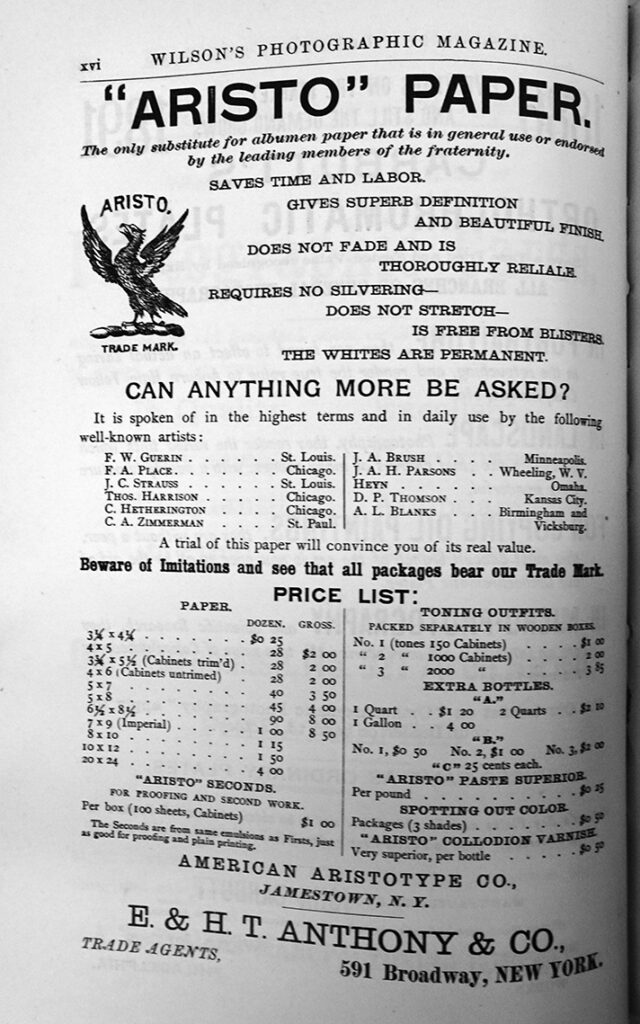

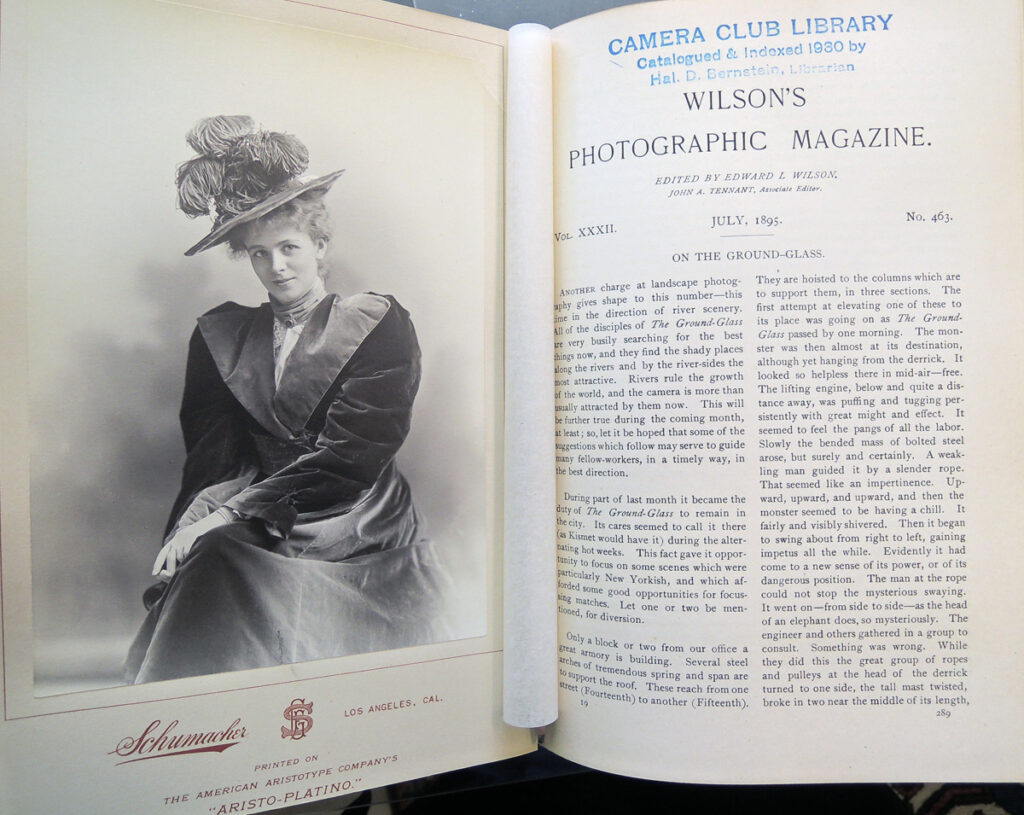

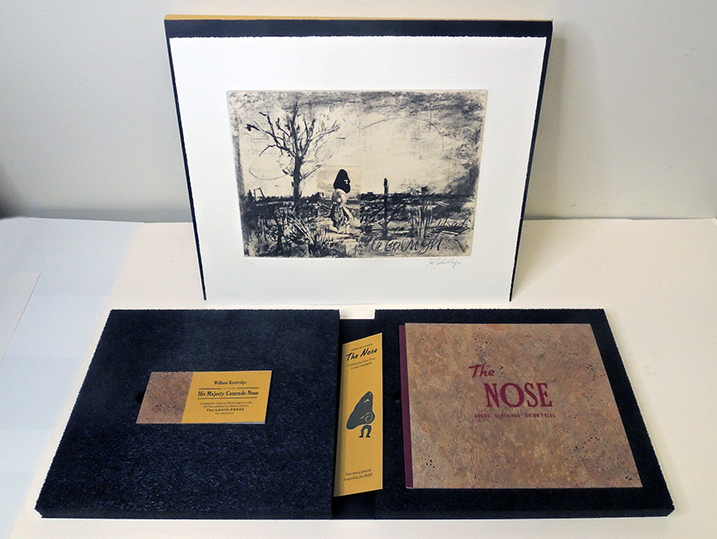

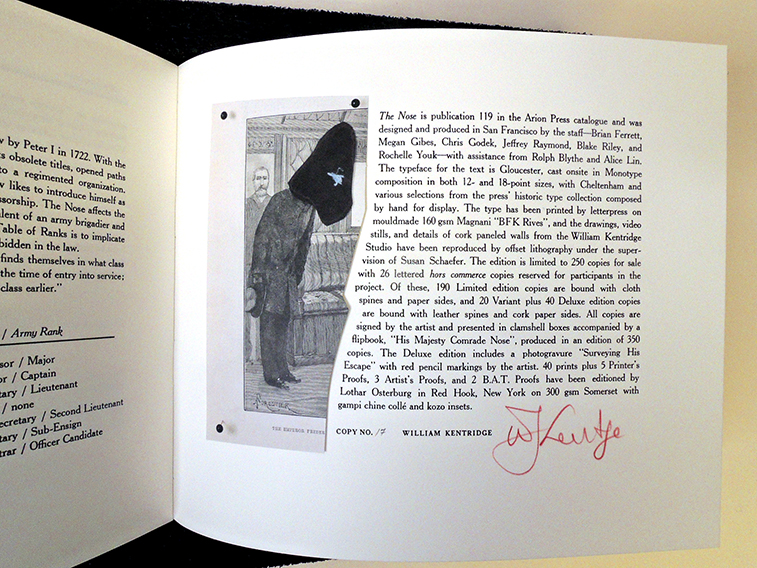

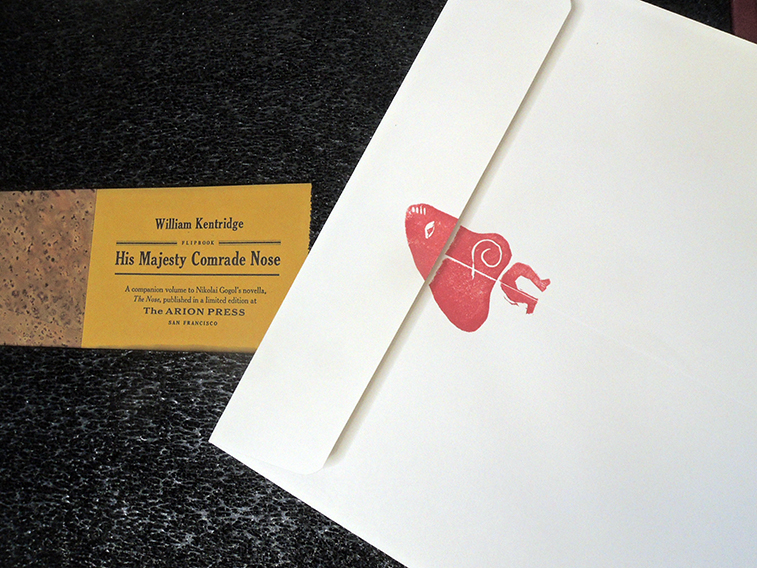

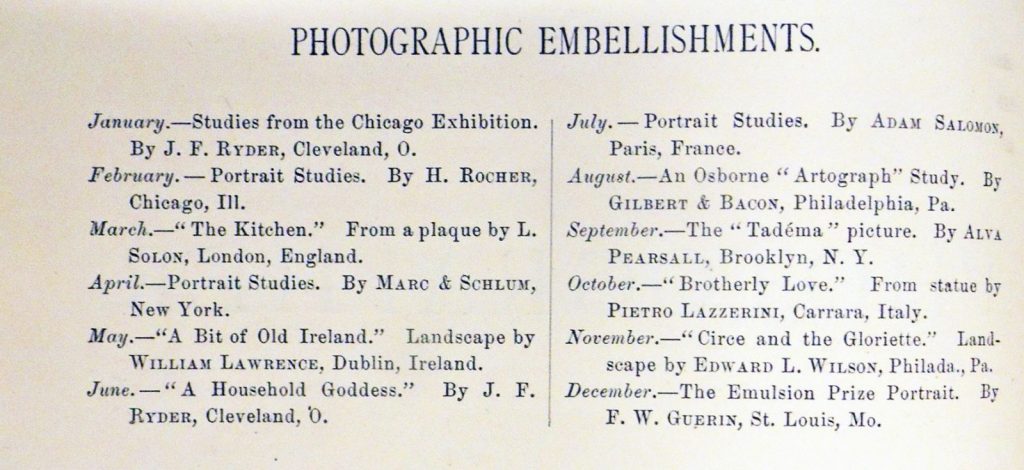

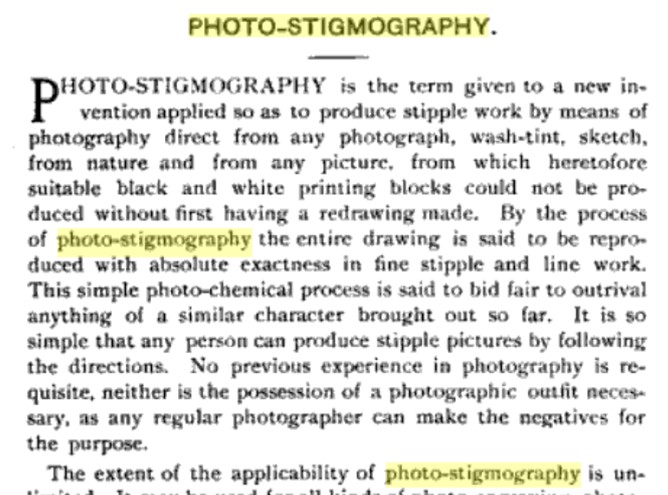

During the late 1870s, Gast worked with William Kurtz, a master of photomechanical printing and the first American to successfully demonstrate the use of three-color photoengraving. Gast developed his own variant processes and began his own company, publishing New Approved Method of Zinc Etching or Photo-zinc-engraving: A Practical Instructor, How to Make Relief Plates, Adapted Especially for Half Tone Reproductions or Photo-nature Engraving in Connection with the Photo-Stigmographic Apparatus in 1886.

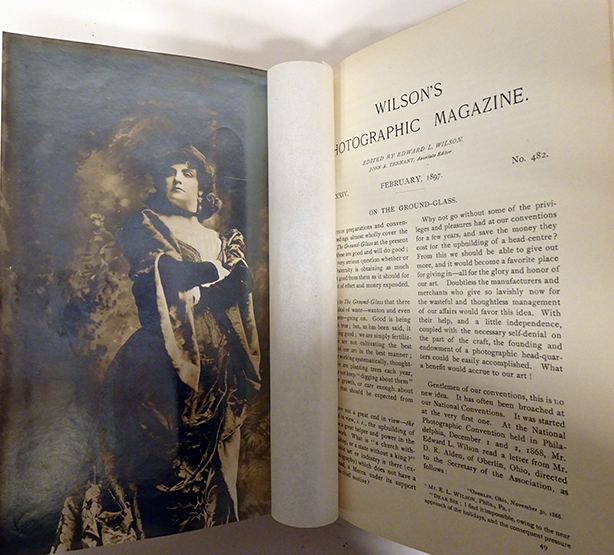

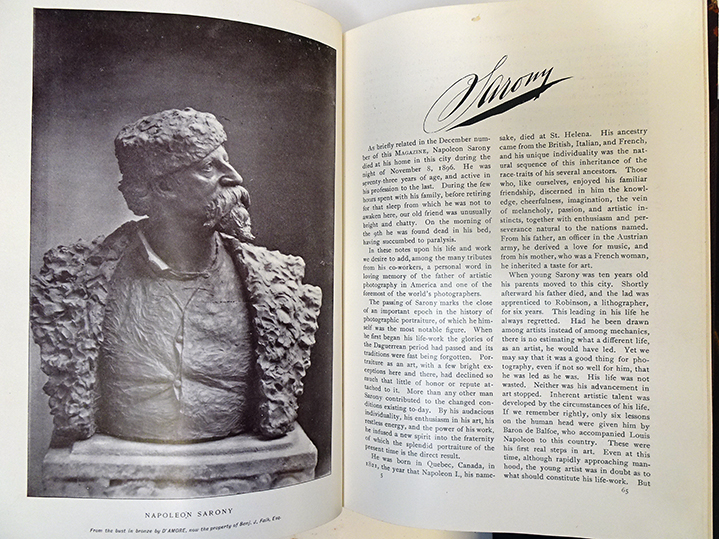

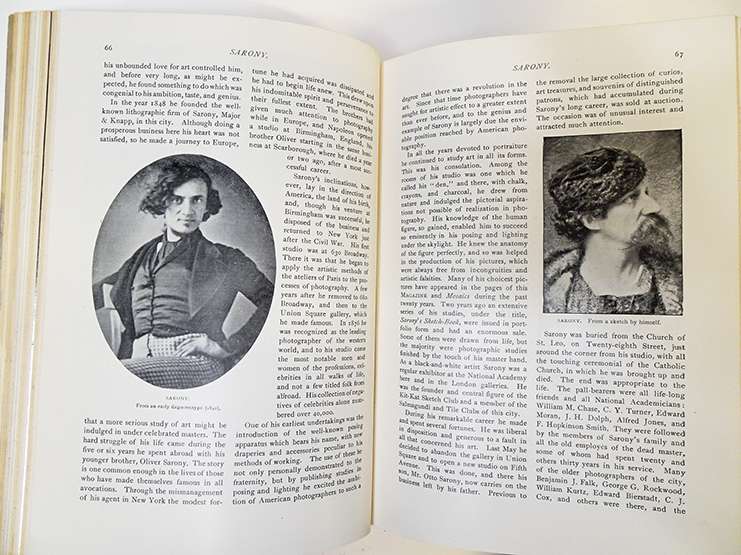

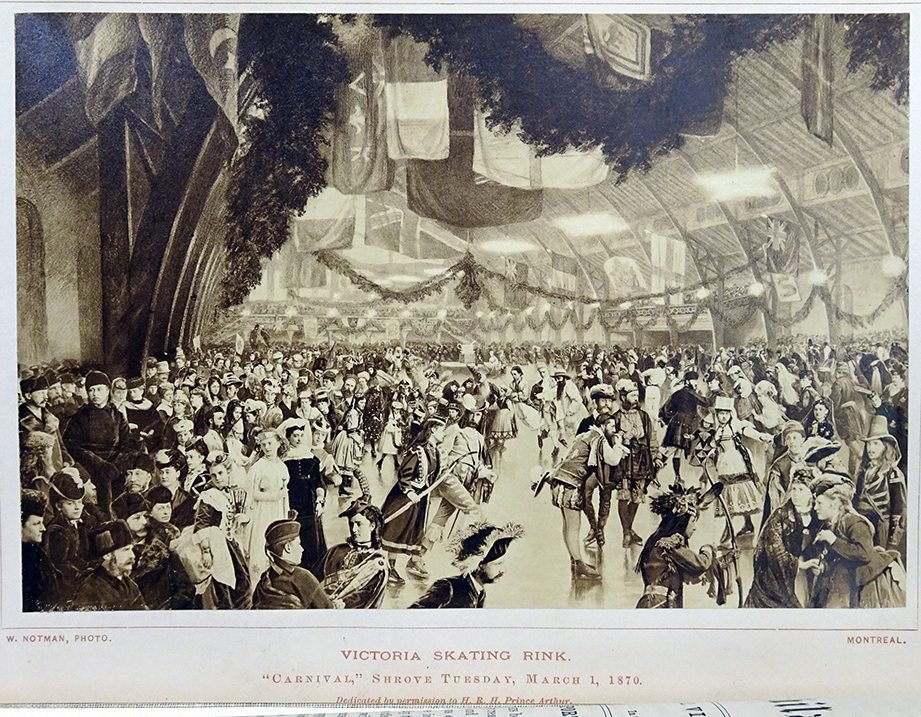

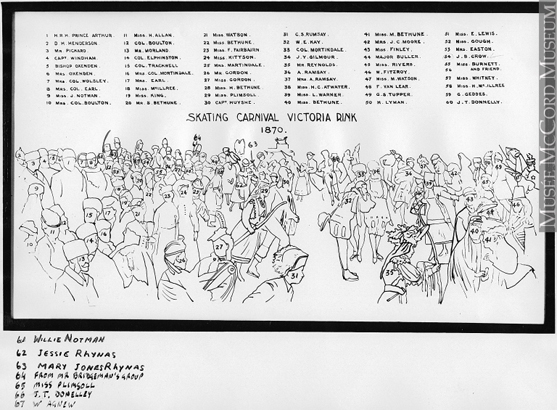

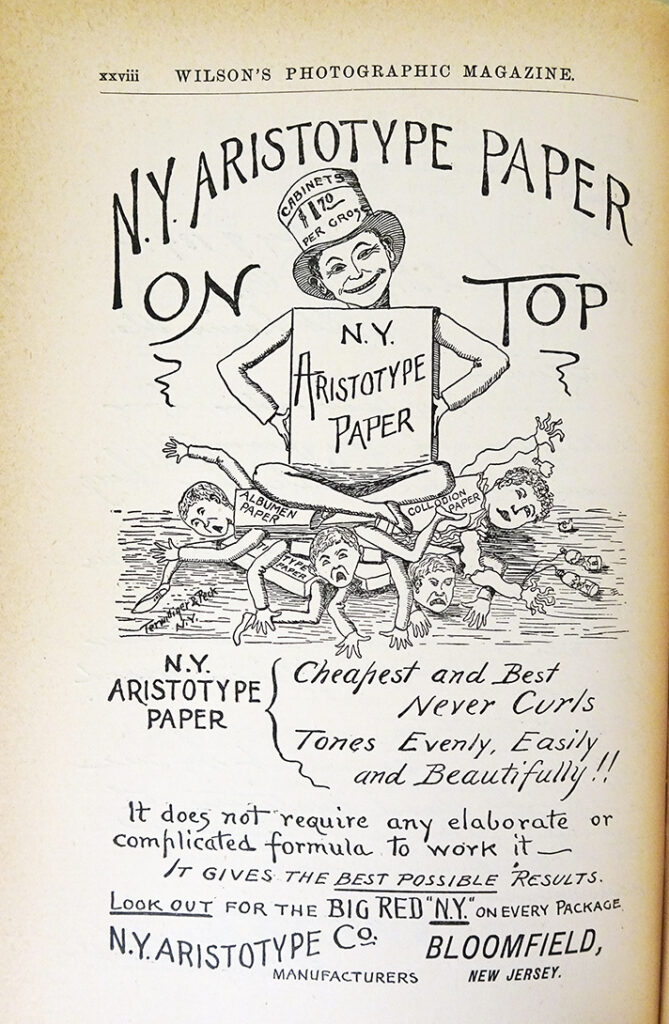

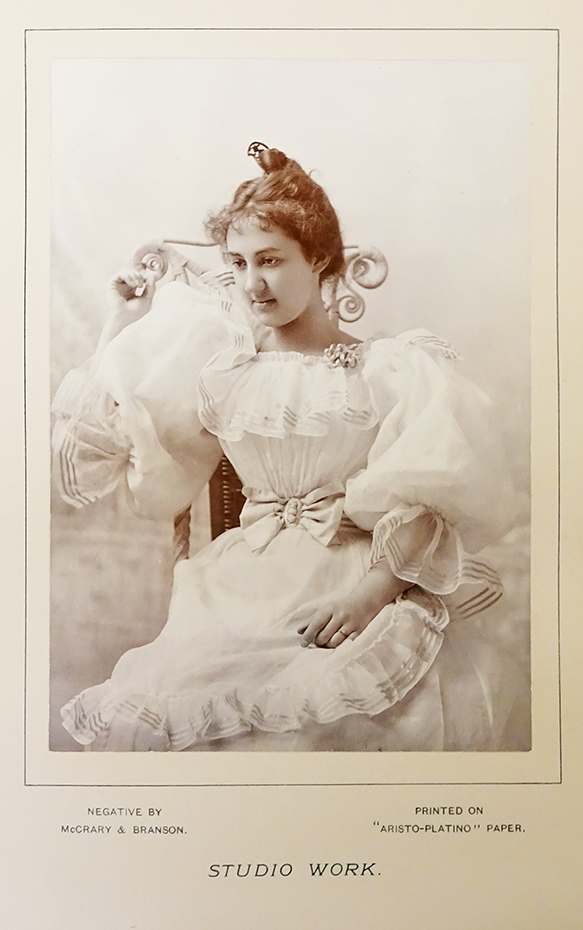

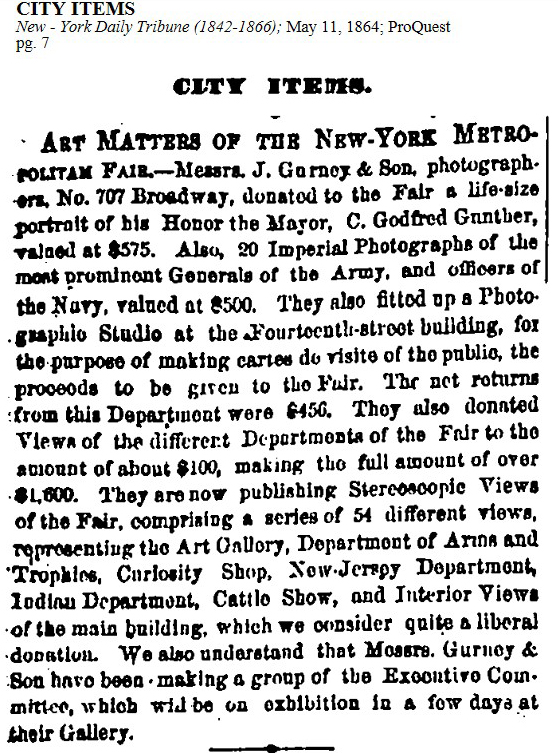

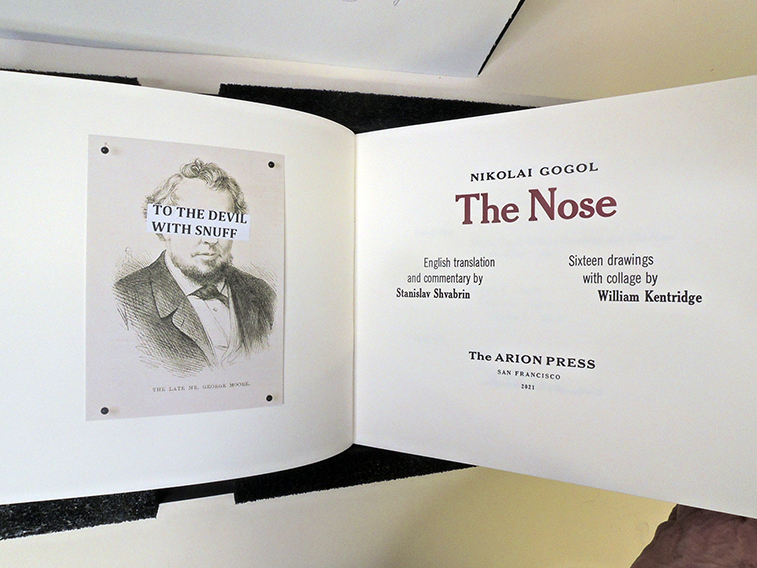

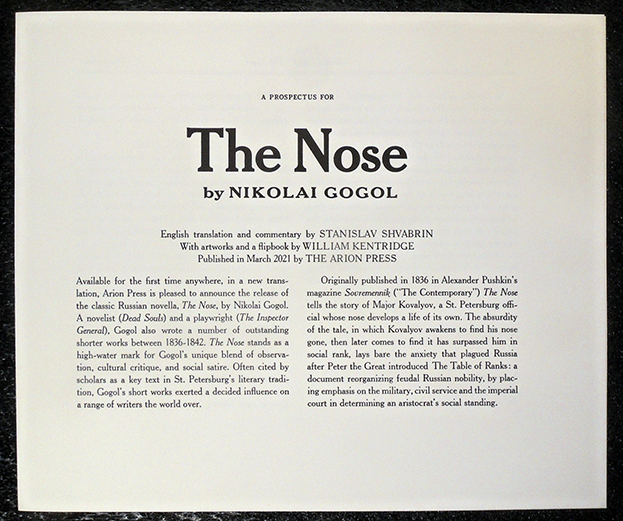

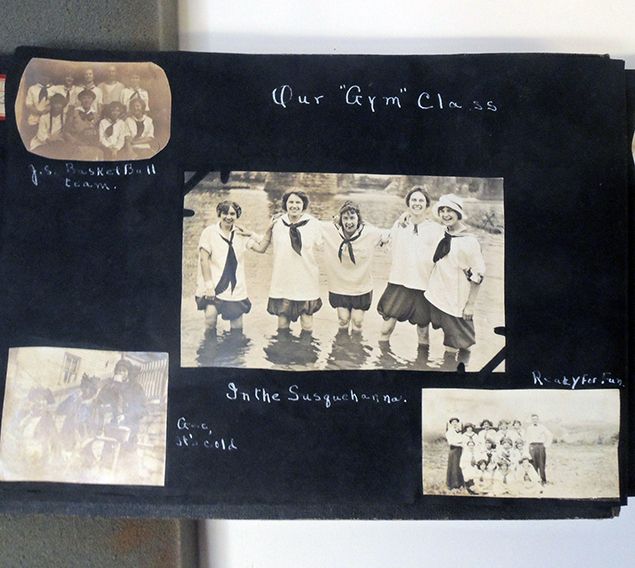

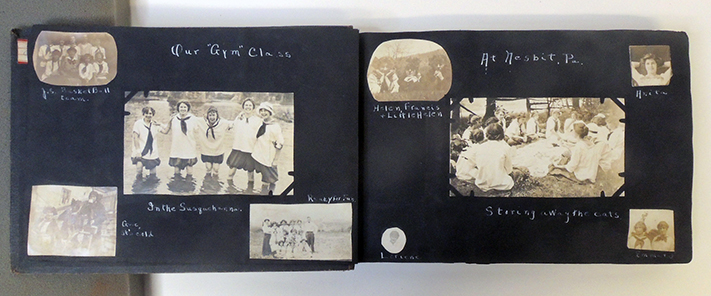

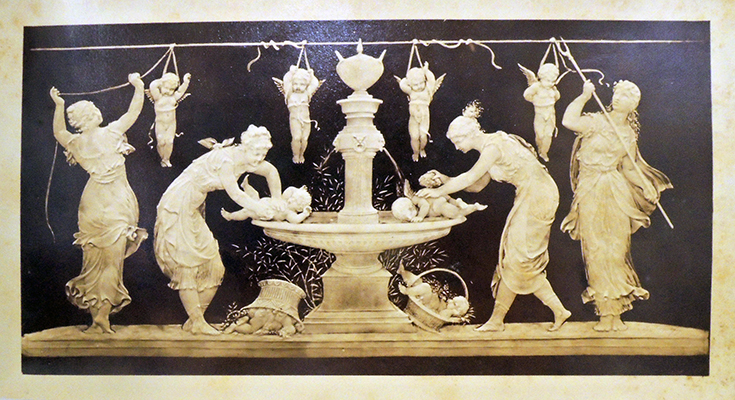

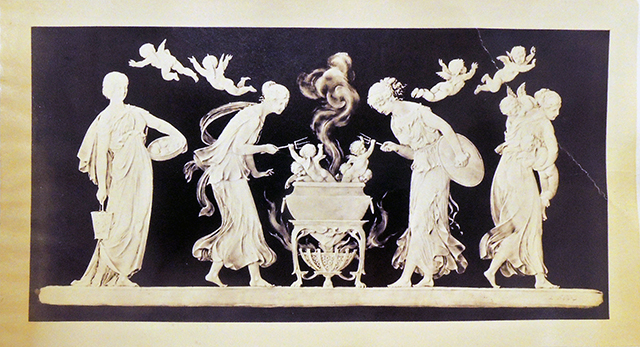

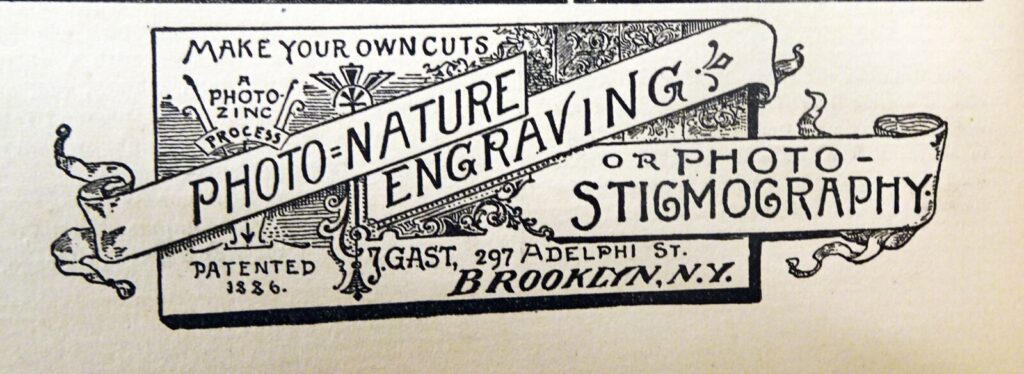

This brought him to the attention of Edward Wilson, editor of The Philadelphia Photographer, who first mentioned Gast’s work in the August 6, 1887 issue. “Much has been written about the steady growth of Photo-engraving and Heliography in general,” commented Wilson, “but this growth, considering the benefit to be derived from these processes, is very slow.” Although he mentions an international group of innovators, it was Gast’s “A New Jersey Landscape” that Wilson used to illustrate his article, noting that the magazine was also advertising the company’s Photo-Stigmography [above].

While Gast had been working in the same field as Wilson for many years, he is incorrectly listed as T. H. Gast, possibly due to the hand-drawn logo. Similarly, when the artist died at the young age of 55, obituaries in multiple papers including the New York Tribune and the Brooklyn Standard print several mistakes. Several credit him as the inventor of the three-colour printing process rather than Kurtz and still others list Gast as establishing the New York Graphic instead of one of their innovative artist/printers. It is not surprising that today, details of his many contributions to the history of printing are misunderstood.

John Gast, a pioneer of the “three-colour” process, died in Brooklyn, N.Y., July 26th, aged fifty-five years. He was born in Berlin, but the family settled in St. Louis. Young Gast returned to Berlin to complete his education. He was graduated from the Royal Academy in Berlin, and returned to St. Louis, where he formed the Gast Lithographic Co. (now Gast-Paul). In three years Gast sold out his interest and went to Paris, where he studied chromo-art under Thürwanger. On returning, he established The New York Daily Graphic in New York in 1871. The Graphic was run successfully for about five years. One of its main features was a page devoted to lithographs made by a special process invented by Mr. Gast. Later on he started the lithographing firm of Gast & Co., now known as Grey & Co. After five years with this company he sold out his interest and started the Photochrome Company. This company used several processes which were invented by Mr. Gast, and soon gained a wide reputation in the lithographic world. He held seven patents on different fine processes for lithographing, but his process which is most widely known is a “three-colour” process. About two years ago Mr. Gast left the Photochrome Company on account of failing health….

“Death of John Gast: He Was a Well-Known Lithographer and Inventor of the Three Color Process,” New-York Tribune July 28, 1896

American Stationer 1886, reprinted in various magazines

American Stationer 1886, reprinted in various magazines