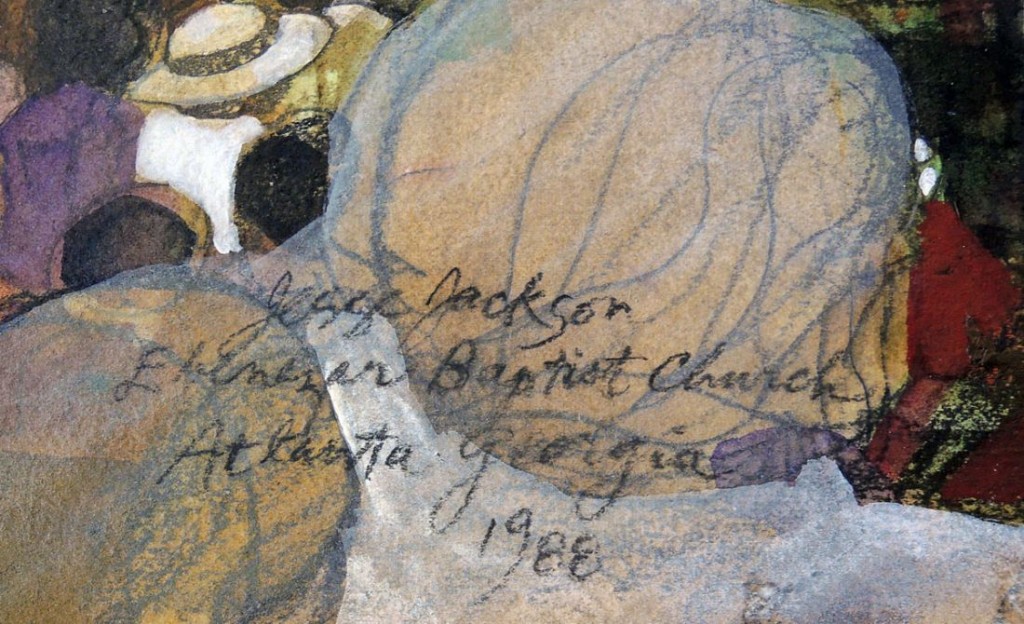

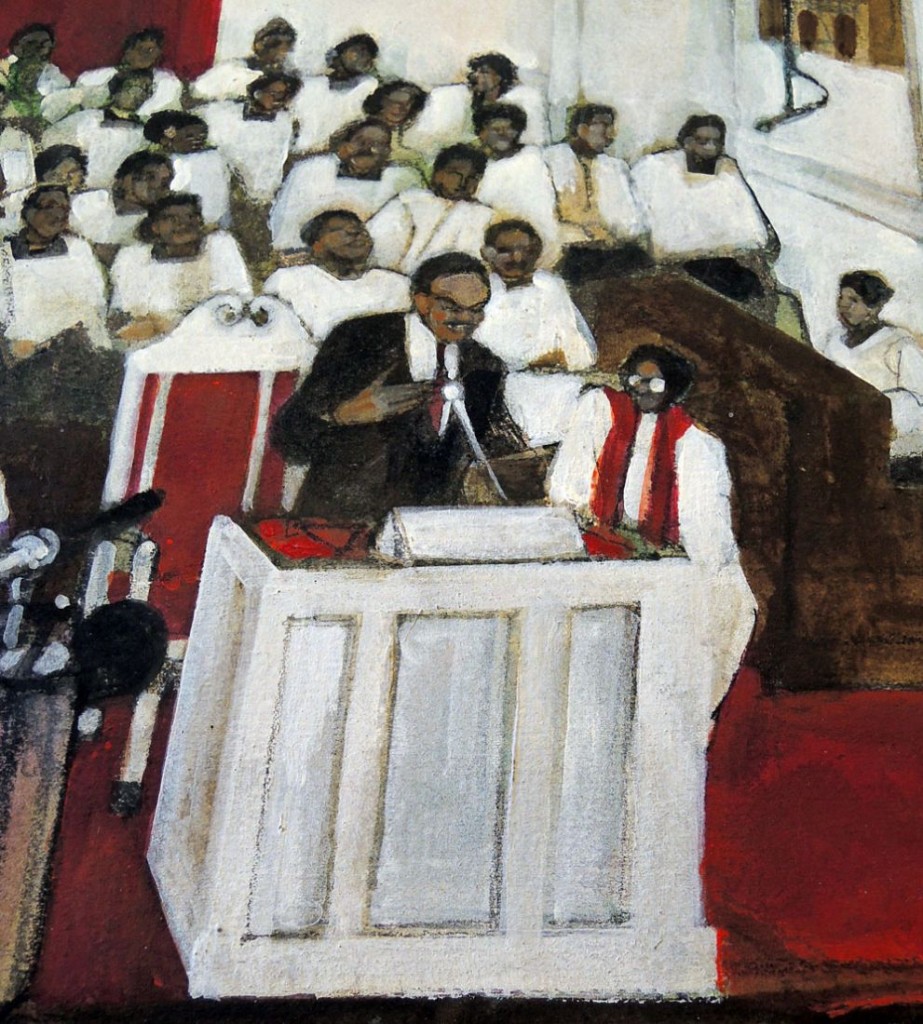

Franklin McMahon (1921-2012), Reverend Jesse Jackson, Ebenezer Baptist Church, Atlanta, Ga. 1988. Graphite, charcoal, and acrylic paint on paper. Graphic Arts Collection GA 2015- in process

ATLANTA, March 6— “The Rev. Jesse Jackson came to Ebenezer Baptist Church today to preach from the pulpit that once belonged to Martin Luther King Jr. and to cloak his Presidential campaign in the glory of the movement that Dr. King led. It was a rich mix of God, politics and history, of civil rights movement veterans, political leaders and average churchgoers, all crammed into the narrow wooden pews of Ebenezer Baptist, two days before the Super Tuesday primaries across the South.

Mr. Jackson, whose relations with Atlanta’s black establishment have often been prickly, seemed to revel in the day. The former lieutenant to Dr. King now stood in his mentor’s church on the brink of a political triumph unimaginable a quarter century ago. It was, undeniably, a religious service, with a pastor noting at one point, ‘It’s not Martin, nor is it Jesse, who’s going to get you to Heaven.’ But after the choir sang ‘God Give Us Faith’ and ‘I’m So Glad I Got My Religion in Time,’ after the reading from the Book of Ezekiel and the communion service, the church moved on to the matters of the world. ‘Bloody Sunday’ Anniversary The Rev. Joseph L. Roberts, senior pastor at Ebenezer, brought the congregation to its feet as he introduced Mr. Jackson ‘as one who hopes to break a barrier that’s never been broken before, but ought to be broken, a barrier that has stood for too long, depriving our people of their rightful due.’

Then Mr. Jackson took his place at the simple white pulpit. He noted that it was the 23d anniversary of ‘Bloody Sunday,’ when civil rights demonstrators were beaten on a bridge in Selma, Ala., as they tried to march for the right to vote. He then paid tribute to John Lewis, now an Atlanta Congressman, who had led that march and been savagely beaten and on this Sunday morning was in a front pew. Mr. Jackson went on to present Super Tuesday as the outgrowth of the bloodletting on that Selma bridge. ‘Tuesday, 23 years later, we can transform the crucifixion,’ he said. ‘And on Tuesday roll the stone away, and on Wednesday morning have a resurrection: new hope, new life, new possibilities, new South, new America.’

‘I’m proud of the the New South,’ Mr. Jackson said. ‘No more governors standing in the school house door, no more dogs biting children.’ But, he continued, ‘It’s not enough to have kind governors and tame dogs. It’s not enough.’ He argued that ‘the fight for economic justice’ was the principle challenge before the South and the nation. It was a fight for the economic rights of garbagemen, Mr. Jackson noted, that drew Dr. King to Memphis, where he was assassinated in 1968. When Mr. Jackson had finished, the congregation sang him on his way with ‘I’m on the Battlefield for My Lord.’ And Mr. Roberts adlibbed, ‘And I promise not to serve him just ’till Super Tuesday but until I die.'”–Robin Toner, “Hosannas to God and Votes for Jackson,” Special to the New York Times, March 7, 1988.

This event was captured by Franklin McMahon, of whom the Times noted, “With sketch pads in hand, Mr. McMahon covered momentous events in the civil rights struggle, spacecraft launchings, national political conventions and the Vatican, turning out line drawings for major magazines and newspapers. Many were later colored by watercolor or acrylic paints, and most rendered scenes in a heightened, energetic style. ‘His goal,’ he said, ‘was to step beyond what he considered the limitations of photography to see around corners.’”–Douglas Martin, “Franklin McMahon, Who Drew the News, Dies at 90,” The New York Times, March 7, 2012.