When Edward Livingston Wilson (1838–1903) started his first magazine, The Philadelphia Photographer, in 1864, his partner in this venture was Michael F. Benerman, foreman at the Caxton Press of Sherman & Company, a large book and job printing firm at the corner Seventh and Cherry Streets. They met through the various print jobs Benerman did for the photography studio of Frederick Gutekunst (1831–1917), where Wilson was an assistant.

Benerman was an experienced bookman. In 1863, he would have been working on a series for Josiah Whitney’s Geological Survey of California, with maps, lithographic plates, and letterpress text. The firm’s edition of Thomas L. McKenney’s History of the Indian Tribes of North America, begun in 1865, remains one of the most important color plate books produced in America. Wilson was in good hands.

Benerman was an experienced bookman. In 1863, he would have been working on a series for Josiah Whitney’s Geological Survey of California, with maps, lithographic plates, and letterpress text. The firm’s edition of Thomas L. McKenney’s History of the Indian Tribes of North America, begun in 1865, remains one of the most important color plate books produced in America. Wilson was in good hands.

Although Benerman soon stepped back from the day to day operation of the magazine, he continued to print this and other publications for Wilson, under the corporate name Benerman and Wilson.

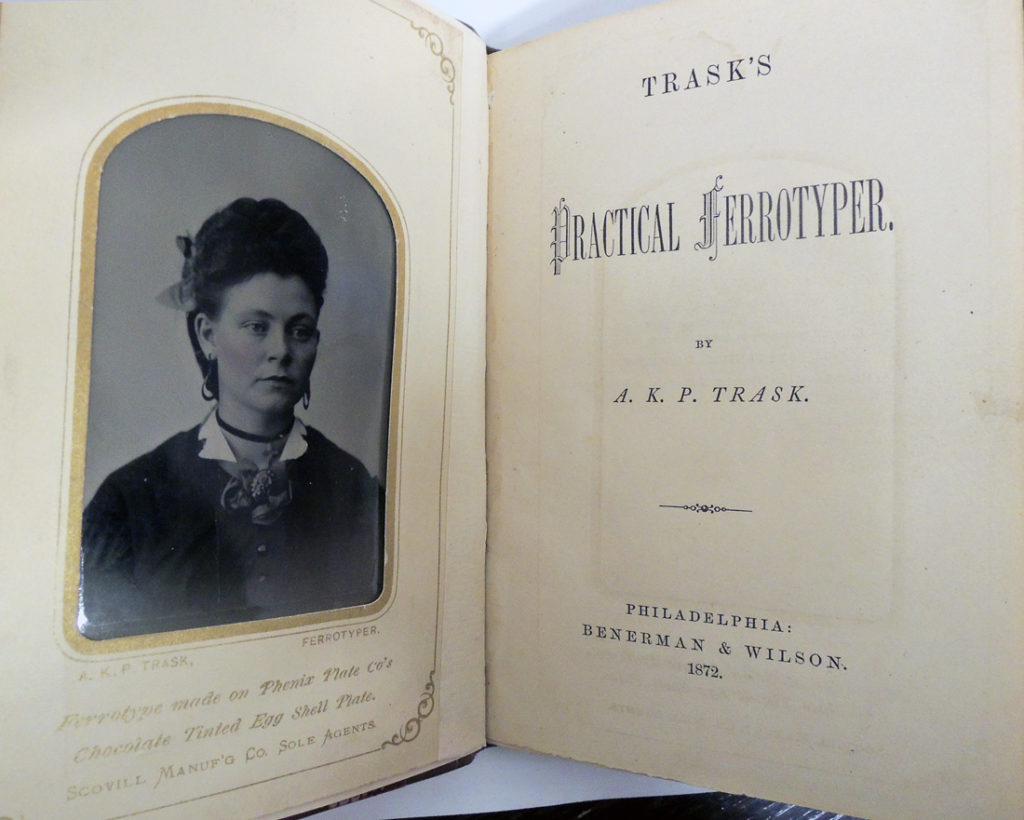

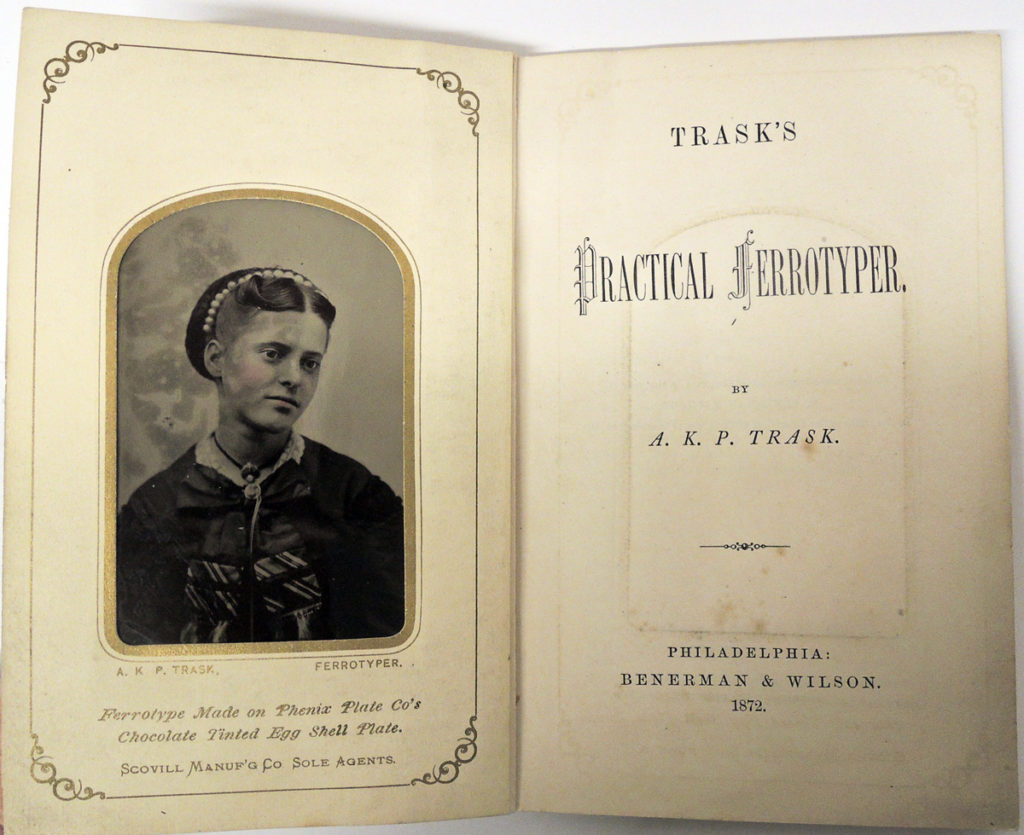

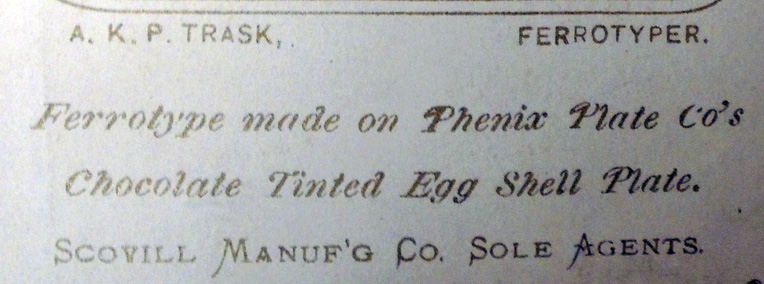

When ferrotypes (also called tintypes) were developed, Wilson was one of the first to published the formula, along with several small manuals complete with an actual tintype as a frontispiece.

Note the process of this one is specified as a “Chocolate Tinted Egg Shell Plate.”

In 1872, the editor of The Photographic Times (distributed inside The Philadelphia Photographer) wrote,

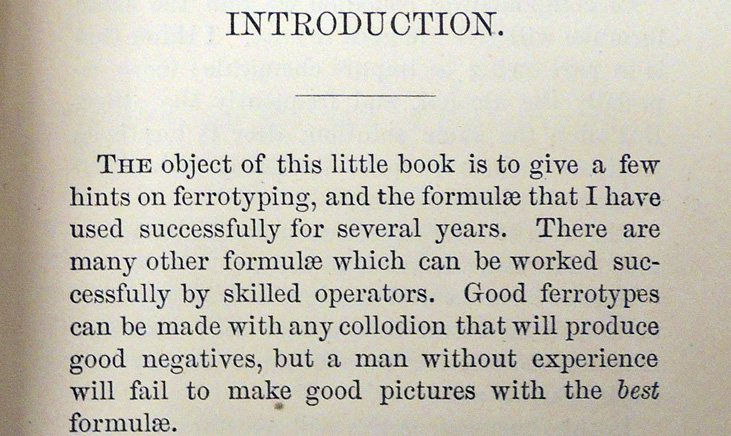

“The publishers have kindly supplied us with some advance sheets of Mr. Trask’s Practical Manual on Ferrotyping, so that we need not wait until its issue to know how complete it is. The reason why so many bad ferrotypes have been made, and why so comparatively few good ones are made, is because no first-class practical ferro’.yper, such as Mr. Trask pre-eminently is, has thought to give us a complete manual of instructions on the subject. As our readers mostly know, we have for two or three years been in the habit of appending to our catalogues some brief instructions in ferrotype making written by Mr. Trask. They were necessarily brief, however, for want of space.

In the forthcoming manual, however, we think everything will be given that will not only enable the careful operator to make the best of work, but it will help him out of trouble should any occur. Mr. Trask very evidently knows his business. We know him to be a most skilful operator, and one who is constantly studying up improvements, taking advantage of everything that will secure the best results. We know of no one more capable of teaching others than he, and he writes just like the practical man that he is. An idea of his book may be had from his Introduction or Preface, from which we extract, viz:”

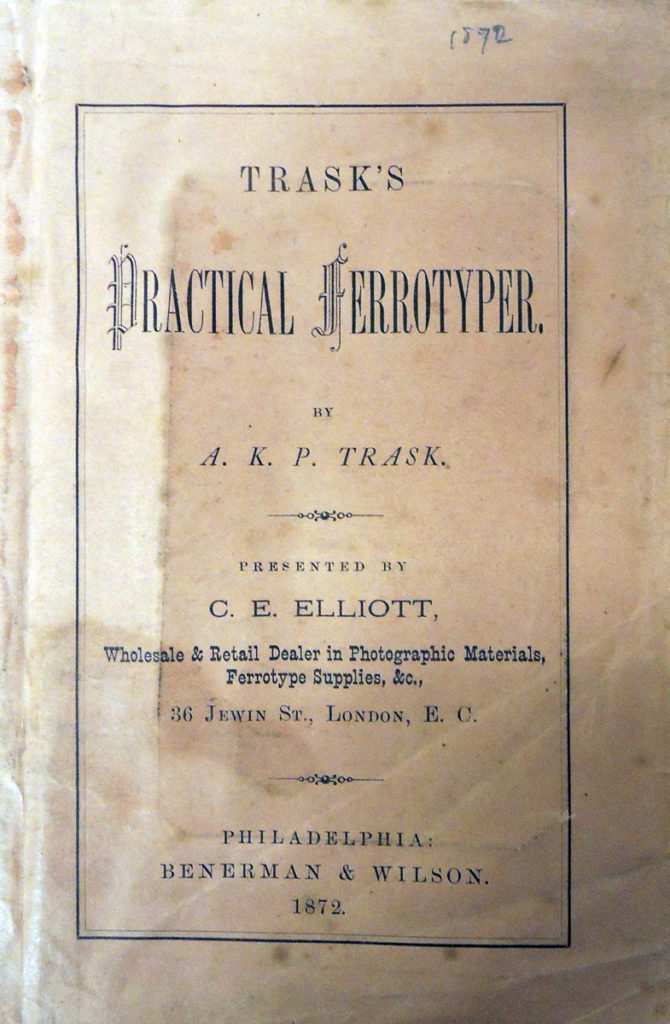

The Graphic Arts Collection recently acquired both the first Philadelphia edition of Trask’s Practical Ferrotyper and the London issue, both 1872. Each has an original tintype frontispiece finished with the “chocolate egg shell” treatment.

Albion K. P. Trask, Trask’s Practical Ferrotyper (Philadelphia: Benerman & Wilson, 1872). One tintype frontispiece. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2017- in process

Albion K. P. Trask, Trask’s Practical Ferrotyper. First London issue. (Philadelphia: Benerman & Wilson, 1872). One tintype frontispiece. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2017- in process.