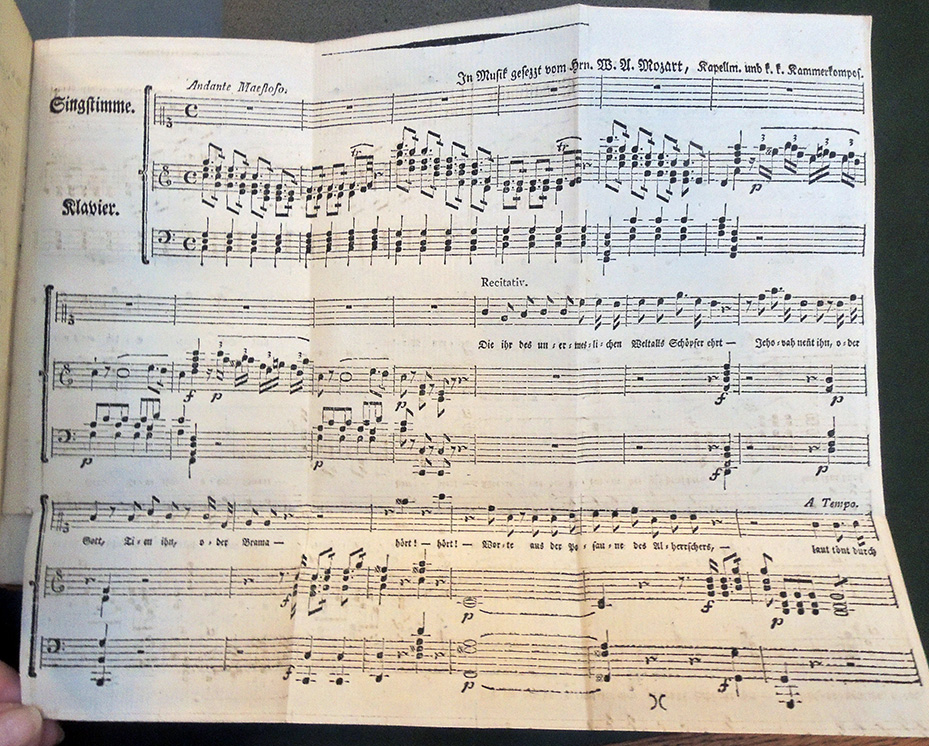

This is the first printed appearance of Die ihr des unermeßlichen Weltalls (also called Eine kleine deutsche Kantate; Little German Cantata) (K619) written by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) in 1791, the same year as he wrote The Magic Flute and also the year of his death. The setting here is for soprano and piano but later composers have arranged the work for orchestra as well as string quartets.

The libretto by Franz Heinrich Ziegenhagen (1753–1806), who commissioned the work from his fellow mason, covers the relationship of the progressive and masonic ideal to the commandment of love as outlined in Ziegenhagen’s book Lehre vom richtigen Verhältniss zu den Schöpfungswerken.

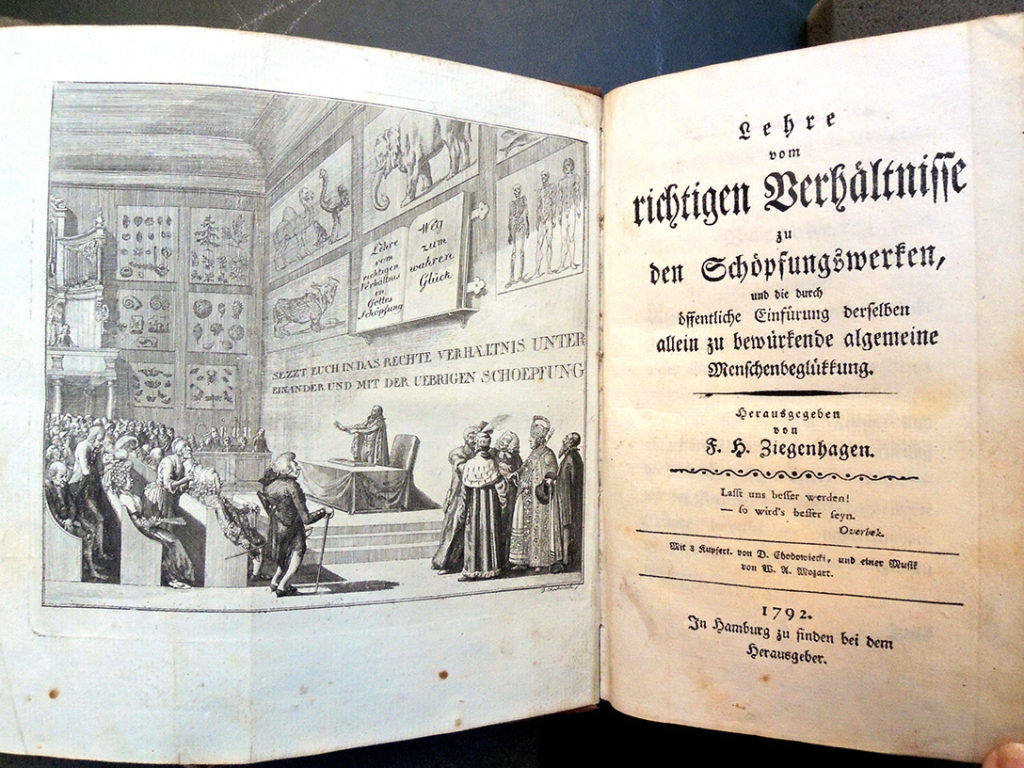

Franz Heinrich Ziegenhagen (1753-1806), Lehre vom richtigen Verhältniss zu den Schöpfungswerken und die durch öffentlicche Einführung derselben allein zu bewürkende allgemeine Menschenbeglückung [=The Teaching of the Right Relationship to the Works of Creation and the General Happiness That Can Only Be Admirable by Public Introduction of Them]. Herausgegeben von F. H. Ziegenhagen… einer Musik von W.A. Mozart (Hamburg: Herausgeber, 1792). Prints by Daniel Niklaus Chodowiecki (1726-1801). Graphic Arts Collection 2019- in process

Ziegenhagen was a German industrialist, freemason and philanthropist who spent his entire fortune trying to realize his utopian ideals in actual communities.

The utopian minded philanthropist Franz Heinrich Ziegenhagen appeared just as “revolutionary” in Hamburg in 1792. …. Ziegenhagen’s utopian concept of a social order of “Liberté, égalité et fraternité” rested upon Rousseauian principles, and he … conceived of agrarian colonies where everything is built upon communal property and communal work. Here the political principle that every member of the community is electable would rule, that is to say that there would be an absolute democracy. Indeed, Ziegenhagen dared even to send an abbreviated version of his essay to the National Convention in Paris in the fall of 1792 with the demand to implement his suggestions as soon as possible in France. However, neither the French National Convention nor the few German princes and universities to whom he sent this book reacted to his appeal. –Peter Uwe Hohendahl, Patriotism, Cosmopolitanism, and National Culture: Public Culture in Hamburg 1700-1933 (Rodopi, 2003)

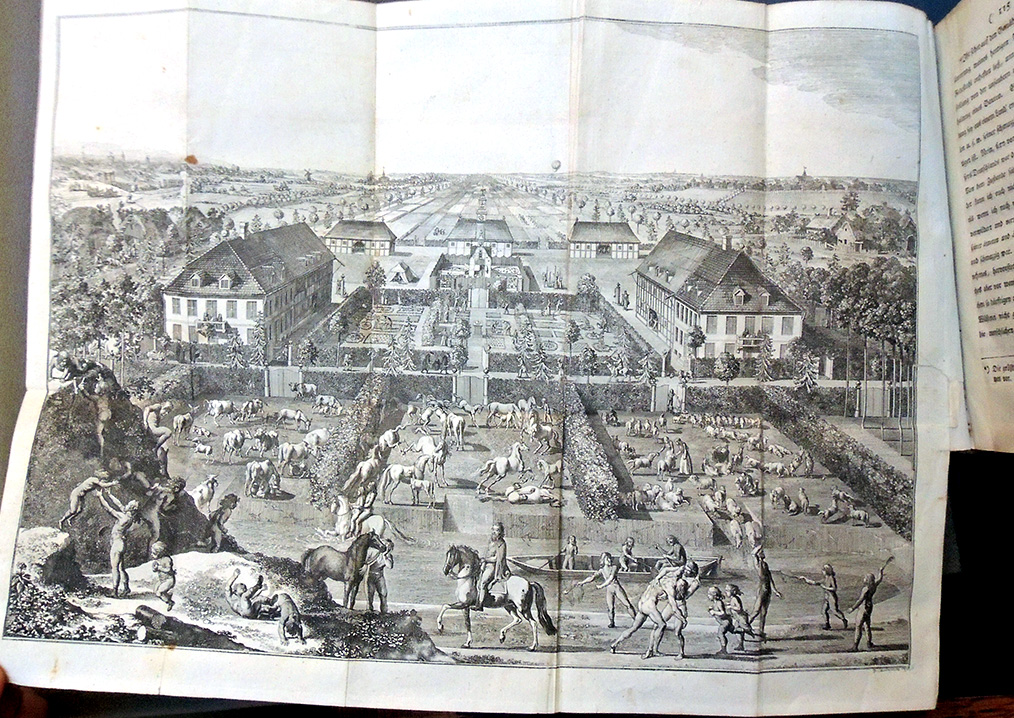

At the heart of the community was Ziegenhagen’s passion for educational reform: An “Erziehungs-kommune,” or educational commune, was to be set up where all children would be educated together without distinction based on birth, wealth or any other kind of status. An emphasis was also to be placed on activities, with practical lessons taught alongside the theoretical.

Ziegenhagen actually founded an agricultural community along these lines in Billwerder, near Hamburg but failed to gain the wider support needed for his initiative to succeed. Forced to sell the property in 1802, Ziegenhagen retired to his home town of Elsass where he committed suicide in 1806.

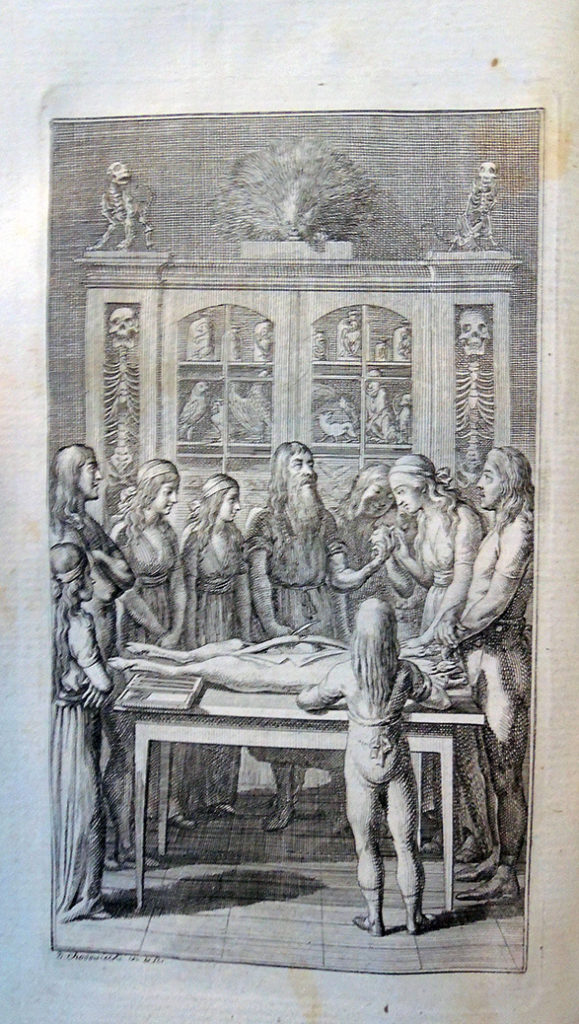

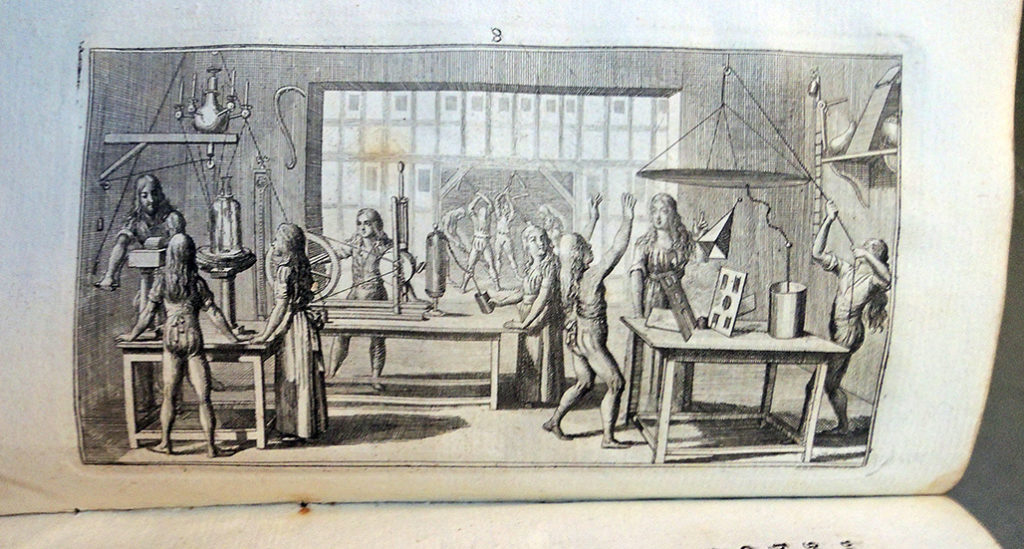

The etched plates are by Daniel Niklaus Chodowiecki (1726-1801), born in Poland but who spent most of his life in Berlin and became the director of the Berlin Academy of Art. His largest folding plate depicts the realization of Ziegenhagen’s utopian project, featuring [above] the author on horseback surveying the busy scene of the community in action. The frontispiece [top] shows a lecture hall with its tall walls filled with illustrations of natural history and students packed into the benches. Six other etchings depict classroom scenes, including a scene with older children in a laboratory, a ‘Kunst-Kammer’ in the background, being taught how to dissect a pig.

…Love me in my works,

Love order, proportion, harmony!

Love yourselves and your brothers!

Strength and beauty shall be your ornament

And clarity of understanding your nobility.

Hold out the brotherly hand of everlasting friendship;

It was delusion, not truth, that withheld it for so long.