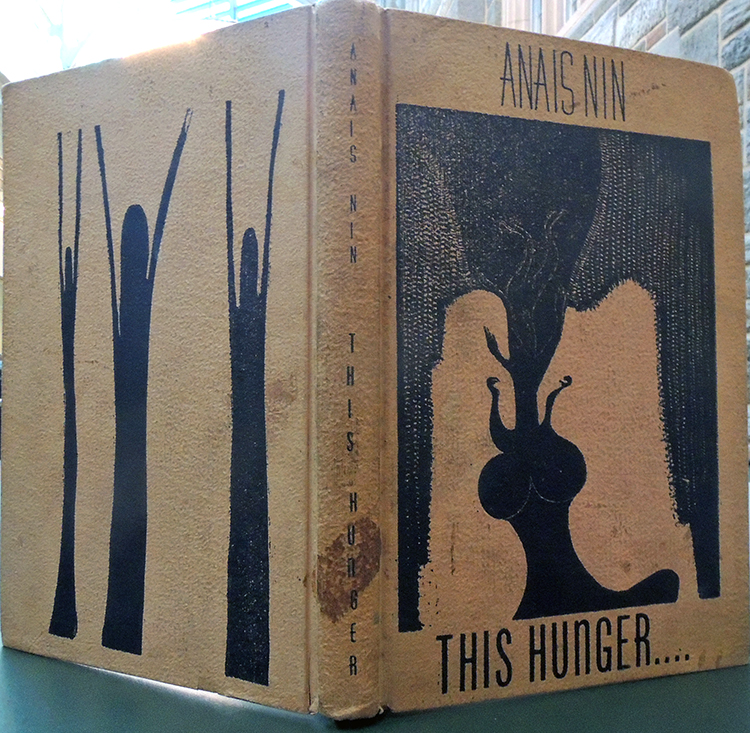

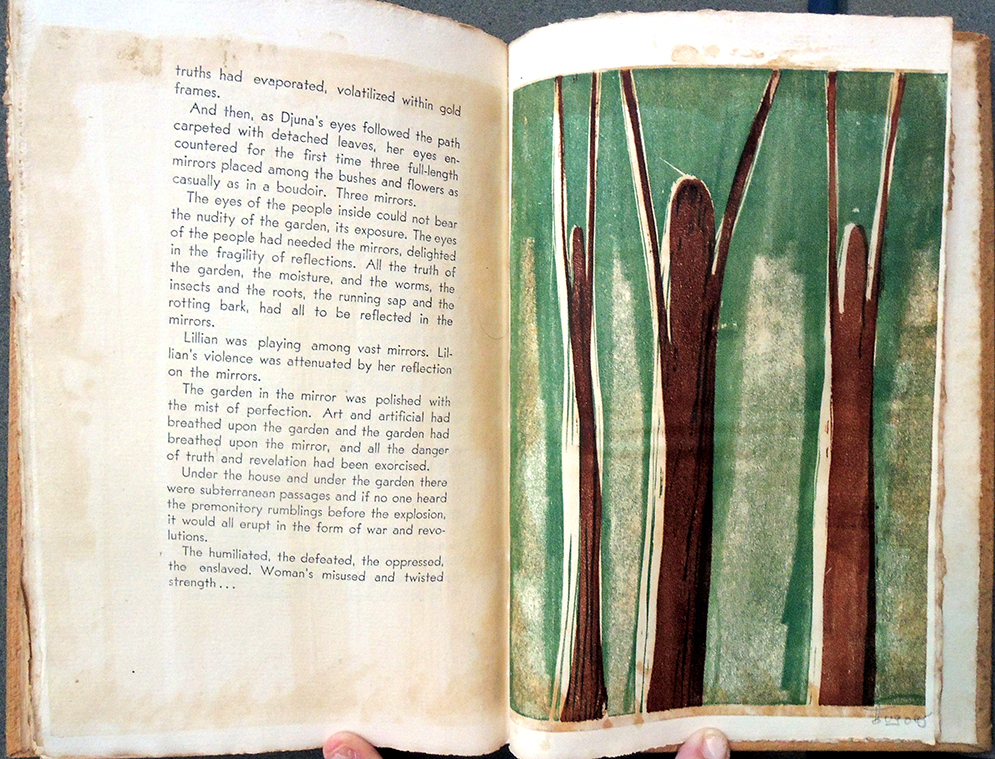

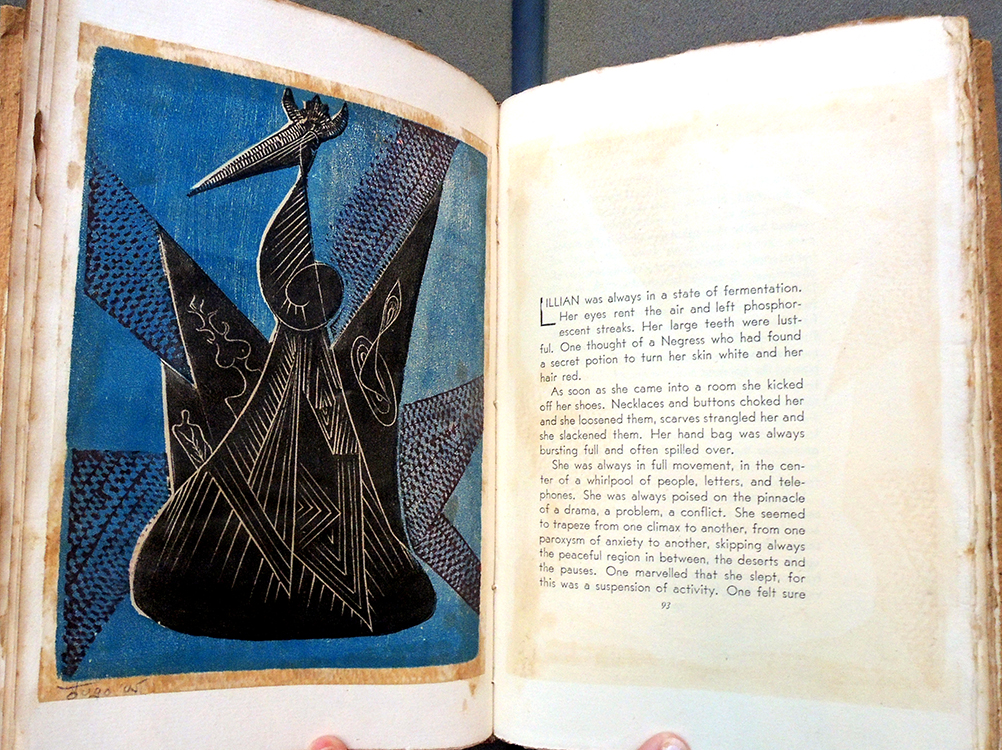

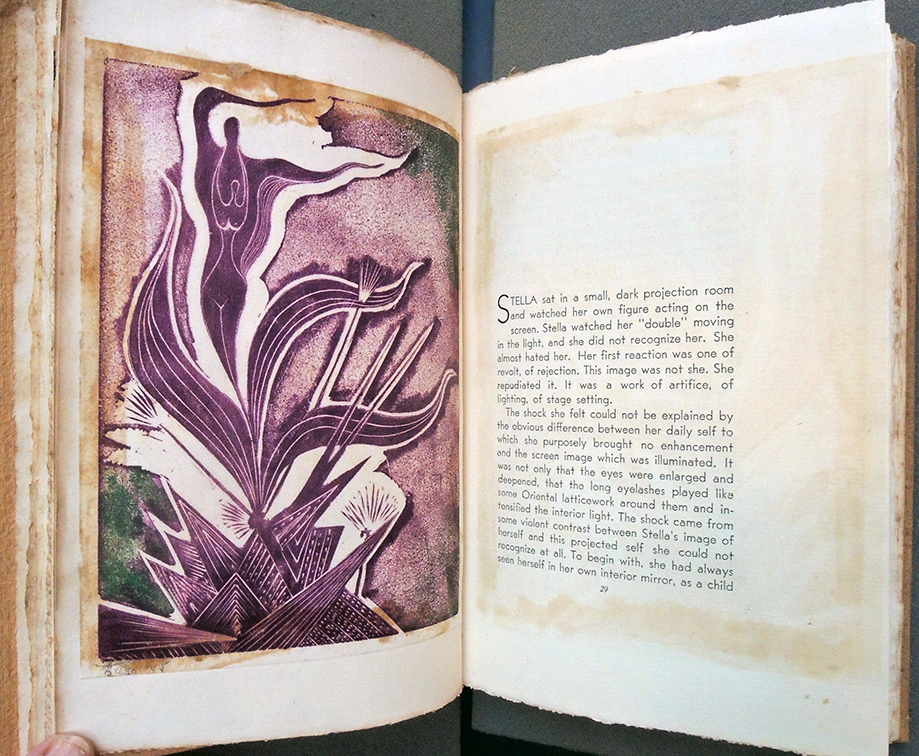

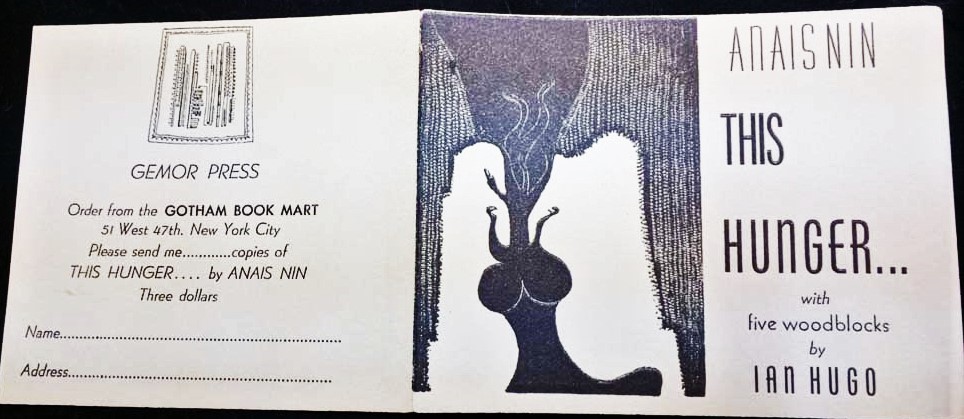

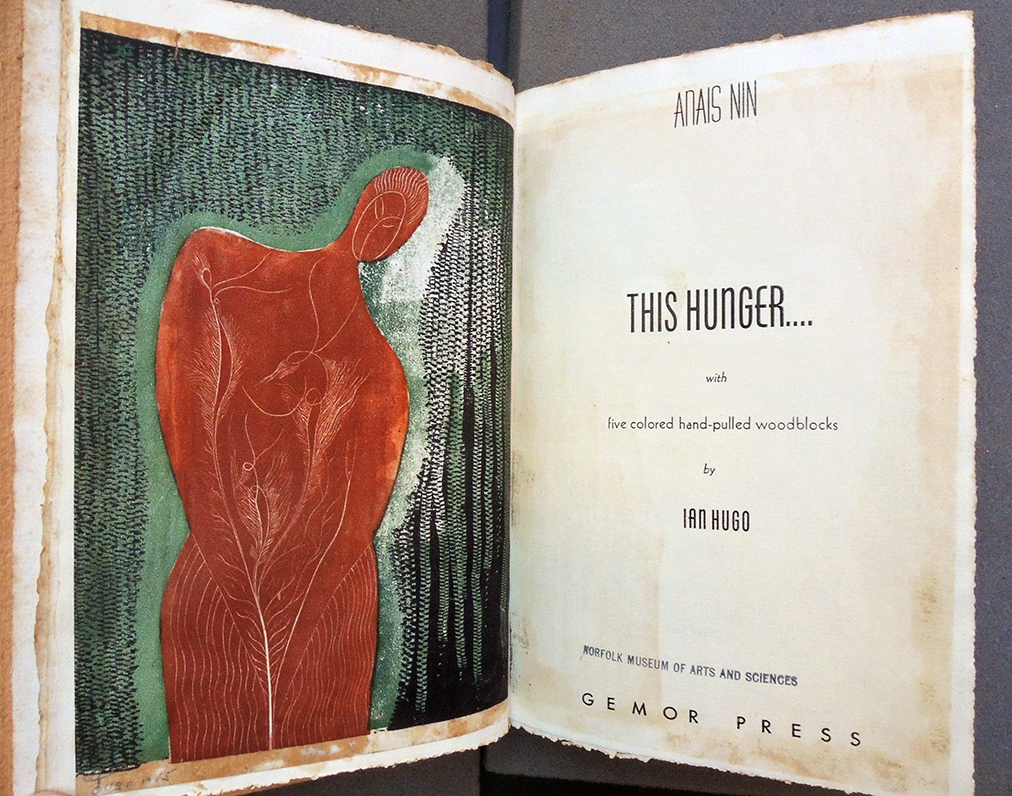

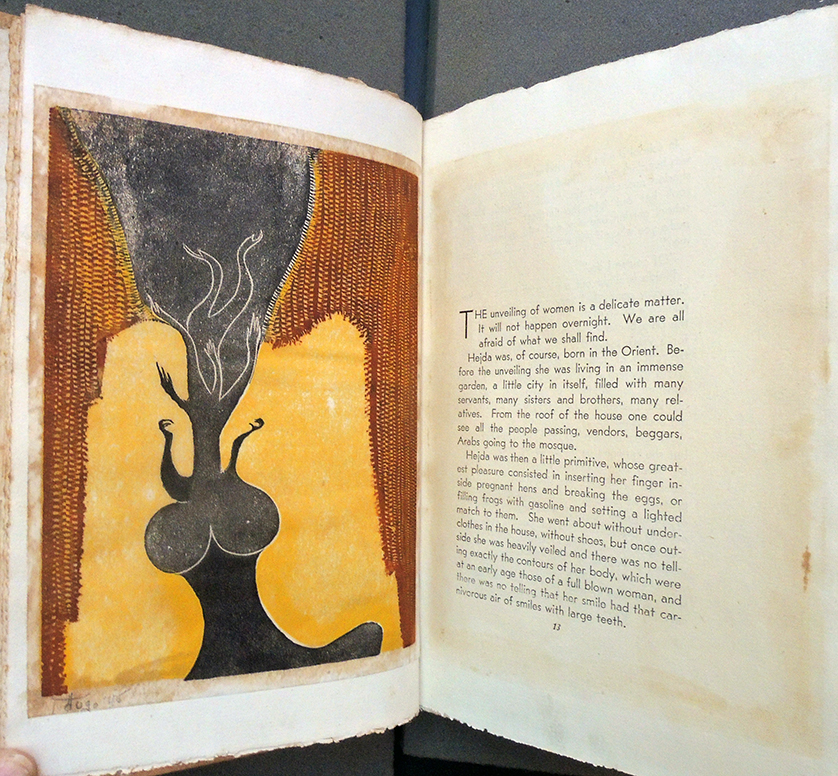

Anaïs Nin (born Neuilly, France, 1903-1977), This Hunger (New York: Gemor Press, 1945). No. 28 of 50 with 5 color woodcuts by Ian Hugo (Hugh Parker Guiler, born Puerto Rico, 1898-1985). Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2020- in process.

Anaïs Nin (born Neuilly, France, 1903-1977), This Hunger (New York: Gemor Press, 1945). No. 28 of 50 with 5 color woodcuts by Ian Hugo (Hugh Parker Guiler, born Puerto Rico, 1898-1985). Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2020- in process.

When Nin’s 1944 book, Under a Glass Bell sold out in three weeks, she and her lover Gonzalo More moved their printing press to a new home on East 13th Street, calling it Gemor Press after More’s initials. She wrote in her diary,

“As Gonzalo wanted the press to seem more businesslike, more impersonal, less like a private press run by writers, we had to find an appropriate place. The Villager had just moved out of 17 East Thirteenth Street. It was a small, two-story house. The ground level with a cement floor was suitable for the printing press. A narrow, curved iron staircase led to the second floor, which would be perfect for the engraving press. The house rented for sixty-five dollars a month, almost twice as much as the old studio on Macdougal Street.”

Their first book at the new location was This Hunger…., later expanded and incorporated into Ladders to Fire, She completed it in September 1945, noting in her diary that she “printed the one hundred and eighty-fourth page, the last of the de luxe edition of This Hunger” and went home exhausted. Although More wanted the business, Nin did the majority of the work, printing at least eight hours a day. The move was expensive and she owed money to everyone, saved in part by Henry Miller, another lover, who gave her $1,000, ”the first large amount he ever earned, which helped me pay off debts; with the rest he bought a cottage in Big Sur.”

According to volume 4 of The Diary of Anaïs Nin 1944-1947, in the mid-1940s Nin also had a relationship with Edmund Wilson (1895-1972). In reviewing This Hunger in The New Yorker November 10, 1945, he wrote:

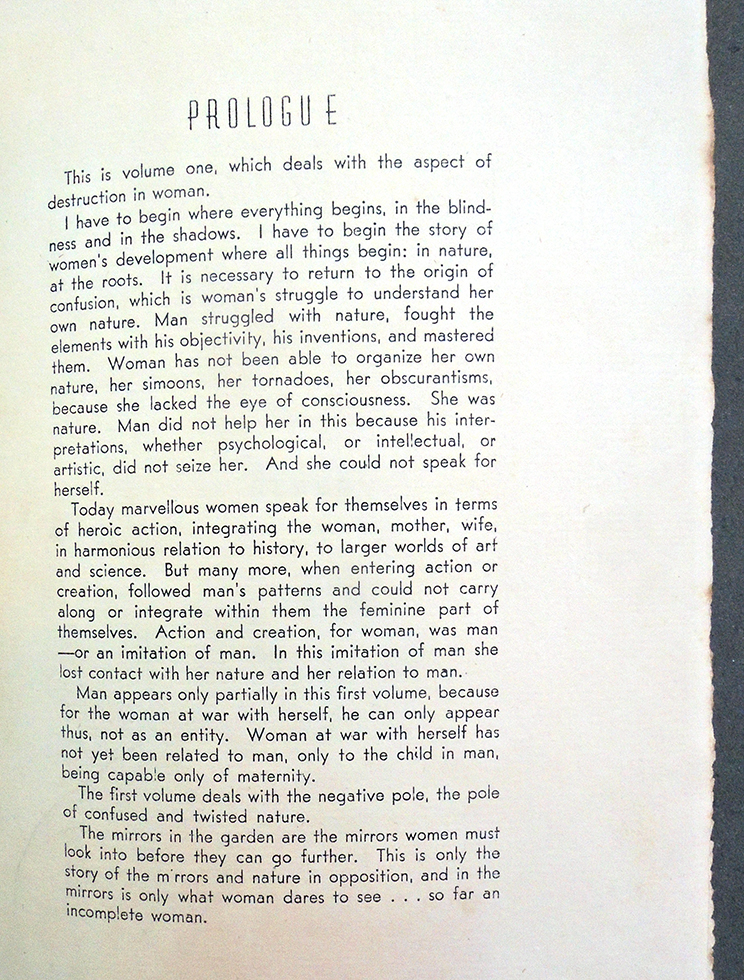

“There is not much expert craftsmanship in This Hunger by Anaïs Nin but it is a more important book than either Marquand or Isherwood because it explores a new realm of material. Even Isherwood can do little more than add to an already long series another lucid and well-turned irony of the bourgeois world on the eve of war. But Anaïs Nin is one of those women writers who have lately been trying to put into words a new feminine point of view, who deal with the conflicts created for women by living half in a man-controlled world against which they cannot help rebelling, half in a world which they have made from themselves but which they cannot find completely satisfactory.”

He ends “I feel sure that Anaïs Nin has still hardly begun to get out of her intelligence and talent the writing that they ought to produce. This new book, like the one before it, has been published by Anaïs Nin herself. Anaïs Nin is at present a special cult, when she ought to have a general public.”

He sent her flowers and a set of Jane Austen. “He was hoping,” Nin wrote, “I would learn how to write a novel from reading her!”