Coming in January 2021 is our first official Wintersession https://winter.princeton.edu/, a two-week experience for Princeton University community members to “experiment and explore through unexpected, active and intriguing non-graded learning and growth opportunities. We seek to use the skills and talents of our whole community: undergraduate students, graduate students, staff and faculty can participate as teachers, learners or both.”

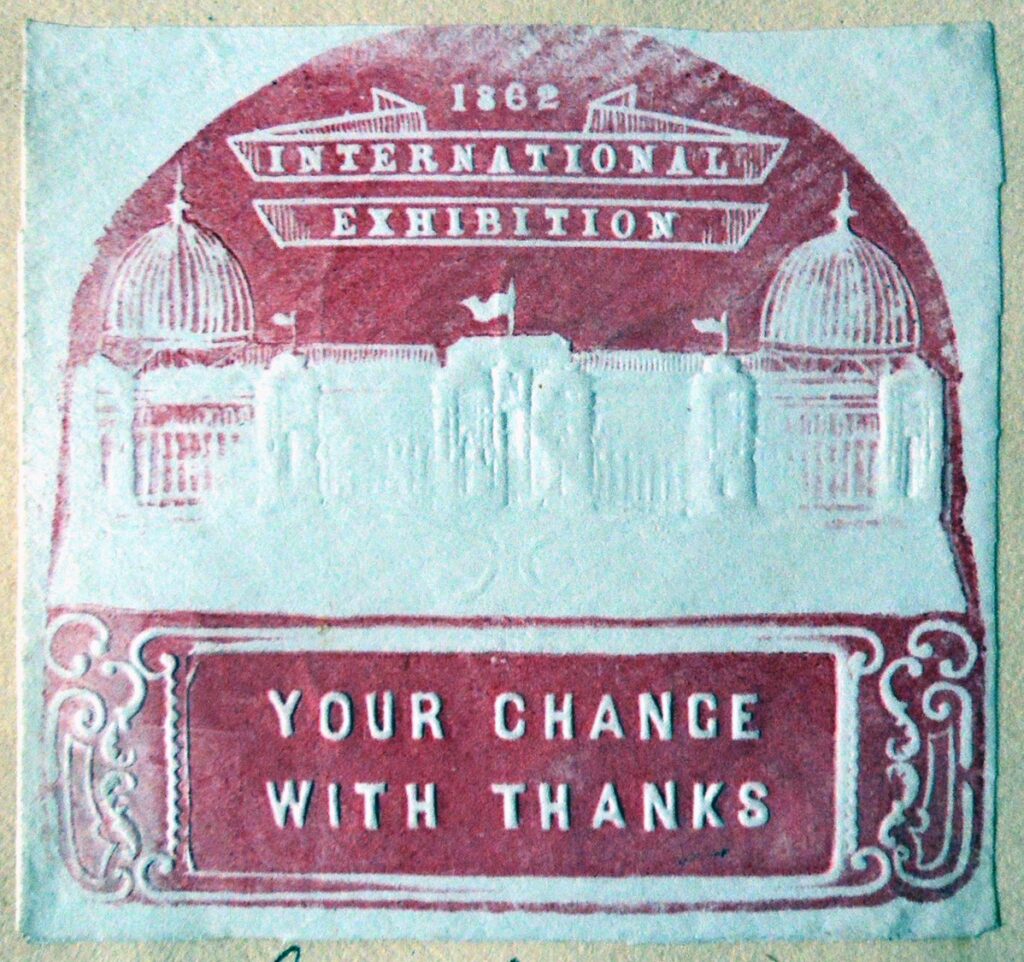

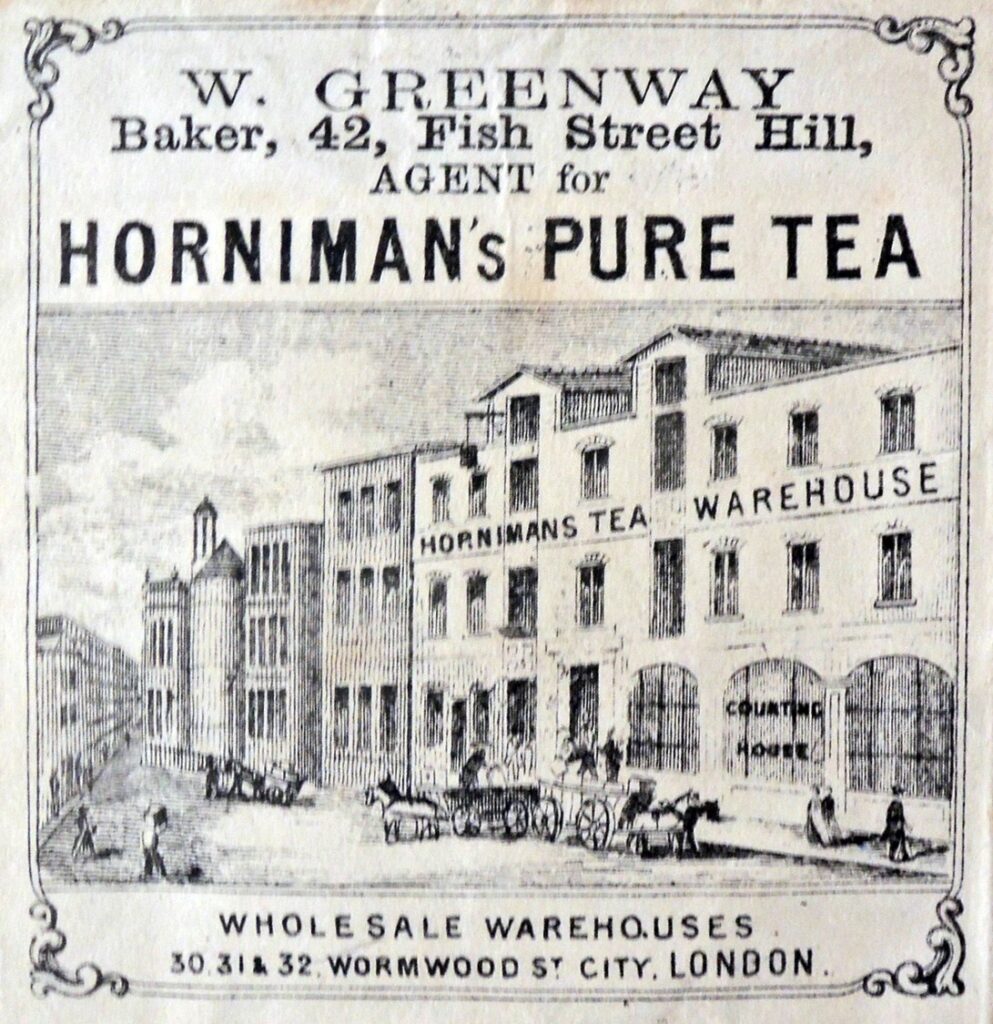

The Graphic Arts Collection will be offering a session entitled “Don’t Touch the Money,” in response to the number of businesses no longer allowing us to pay for goods with coins or paper money, in an attempt to limit the spread of Covid 19. Together, we will compare our current experiences with a time in the 19th and early 20th centuries when it was also not acceptable to received your change directly from the hand of a clerk but instead, any cash returned to the customer would be given in a small, engraved envelope known as a “change packet.”

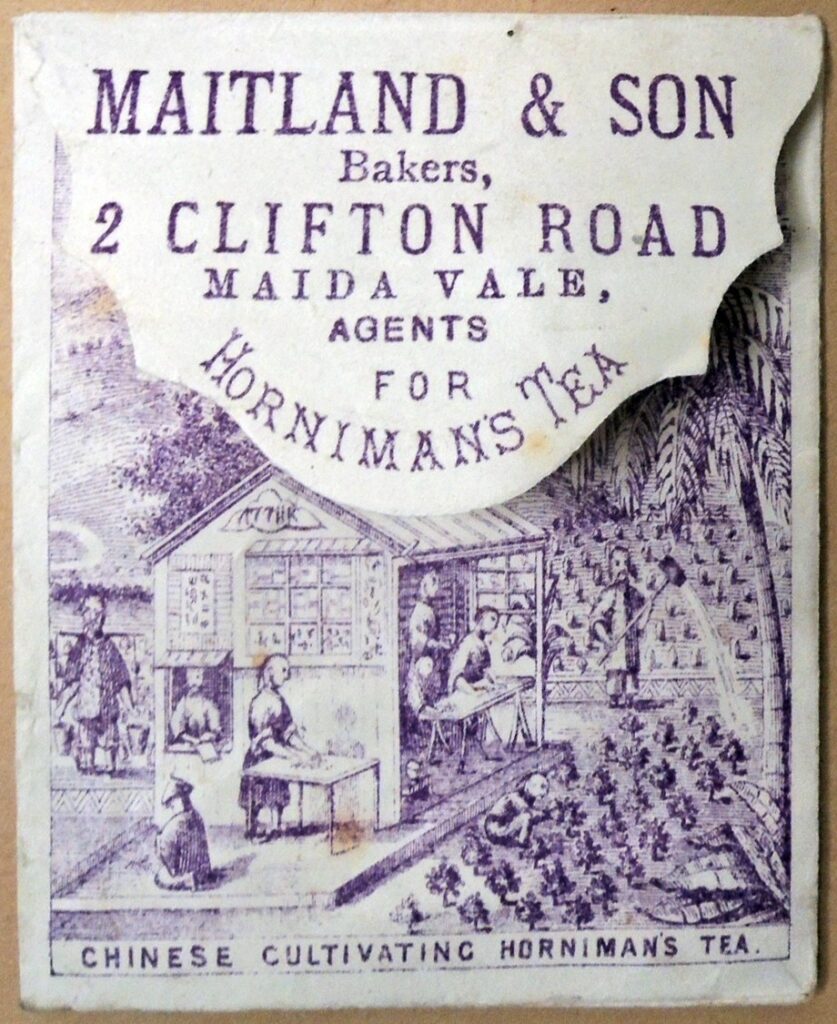

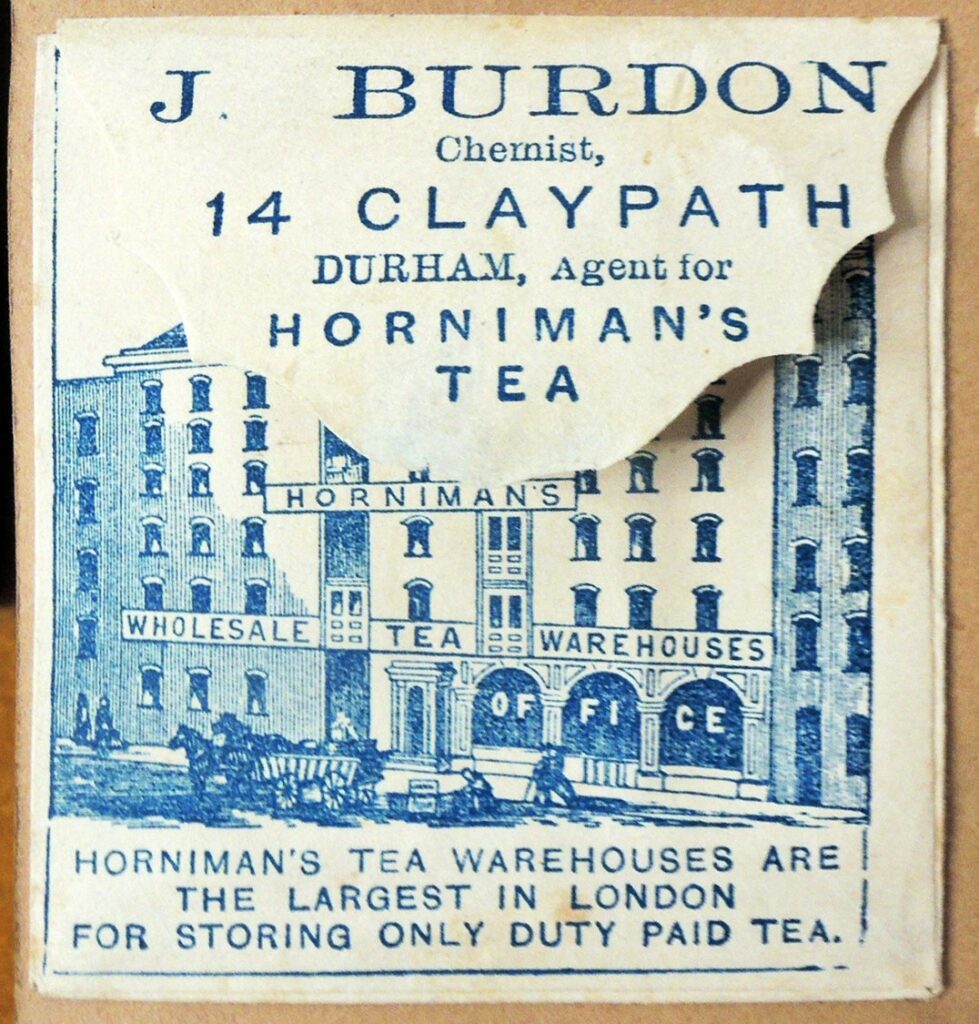

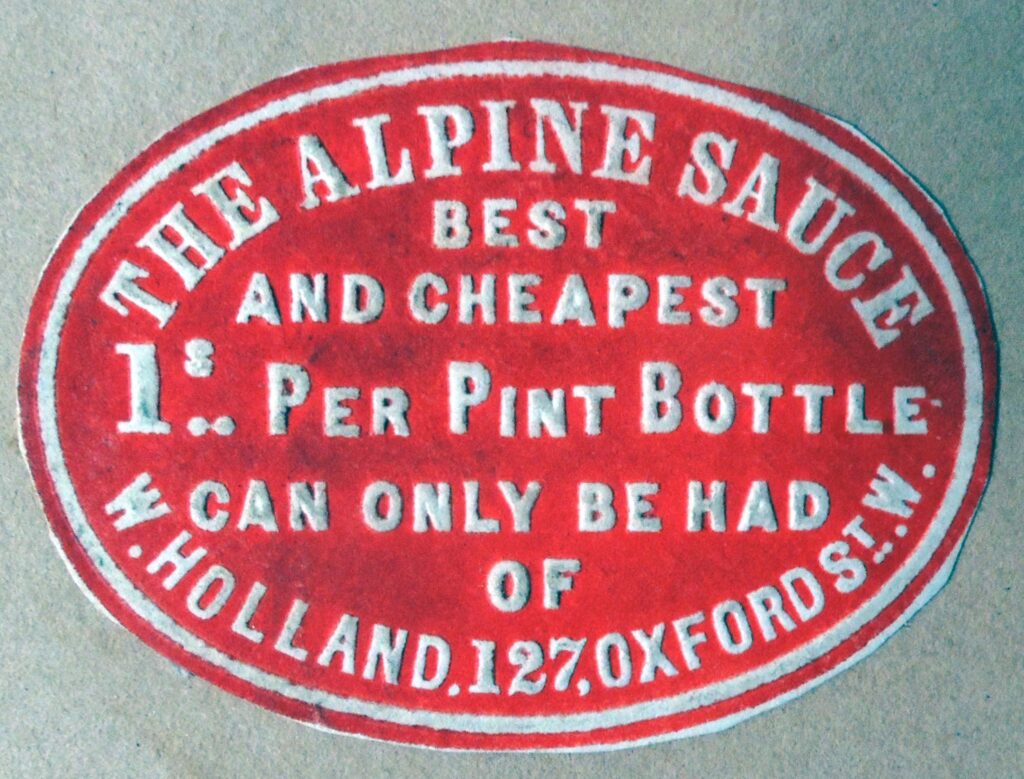

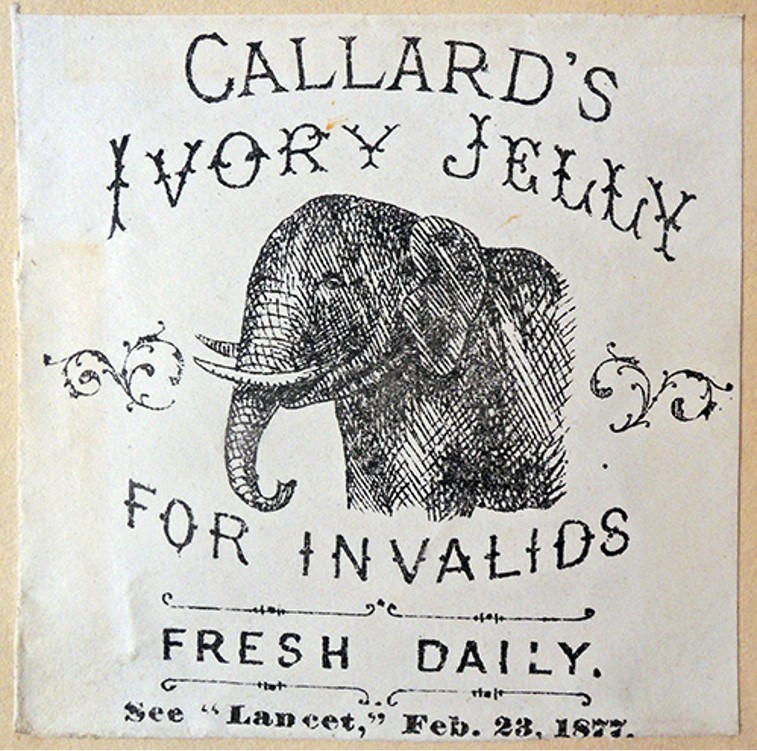

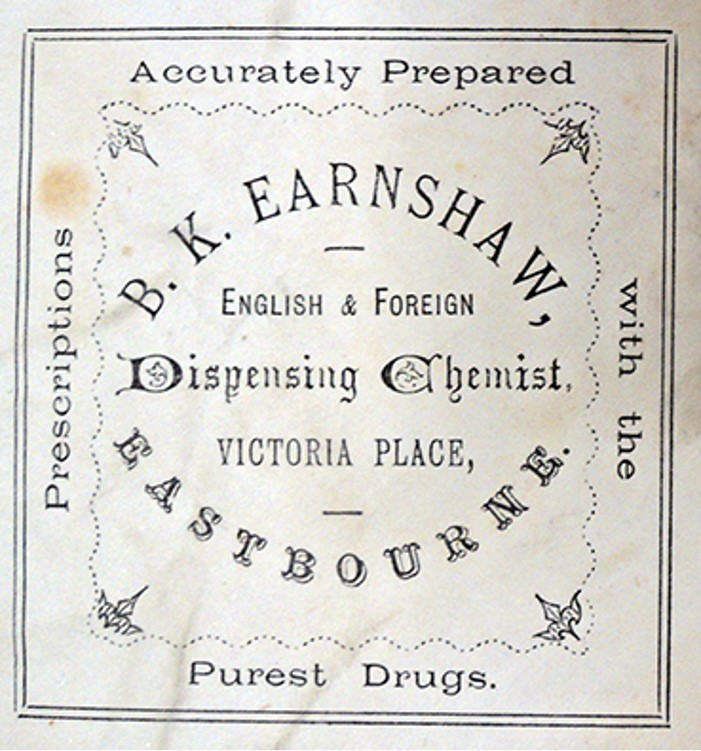

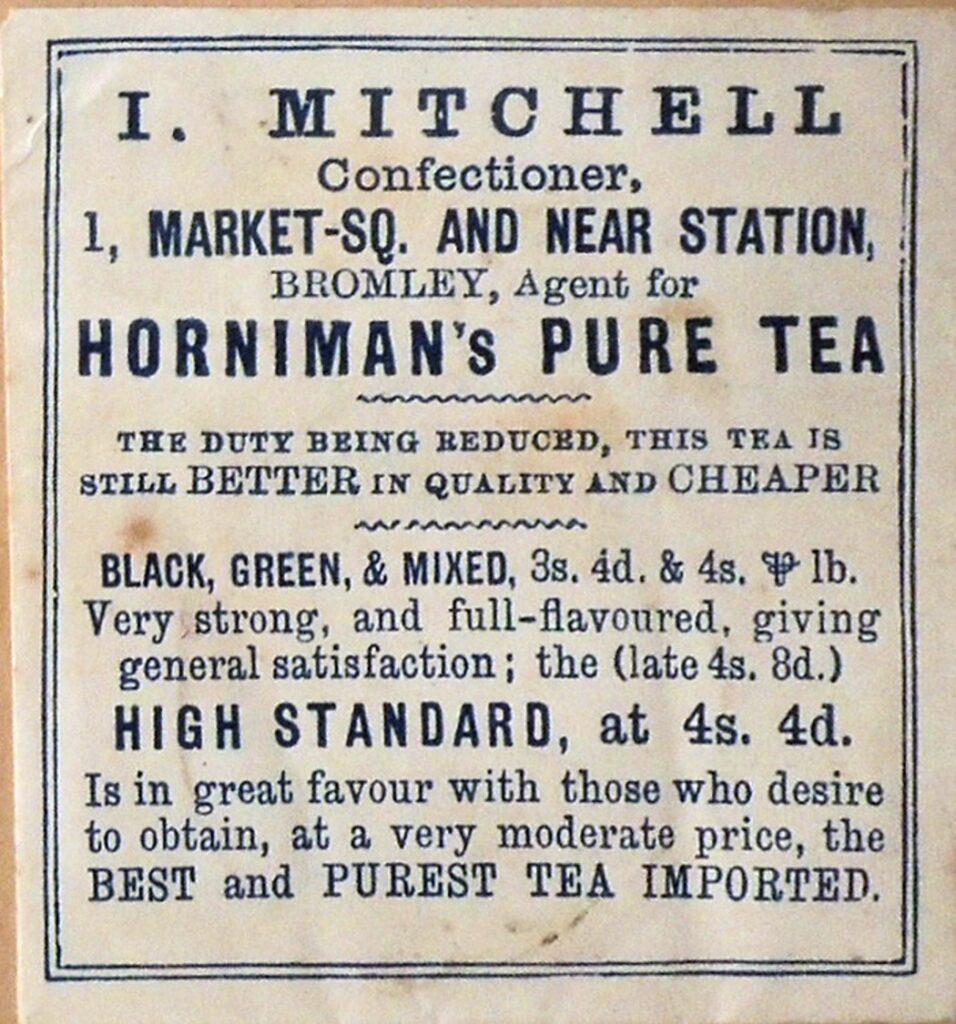

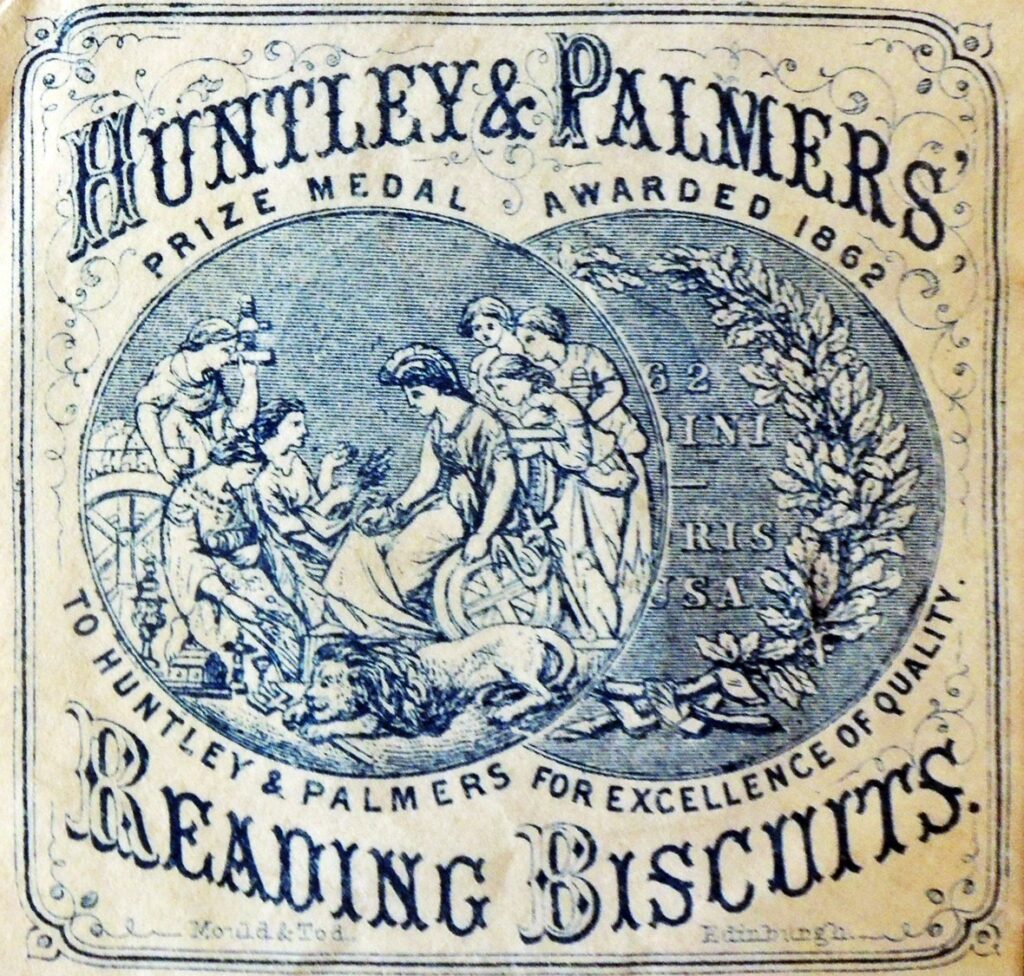

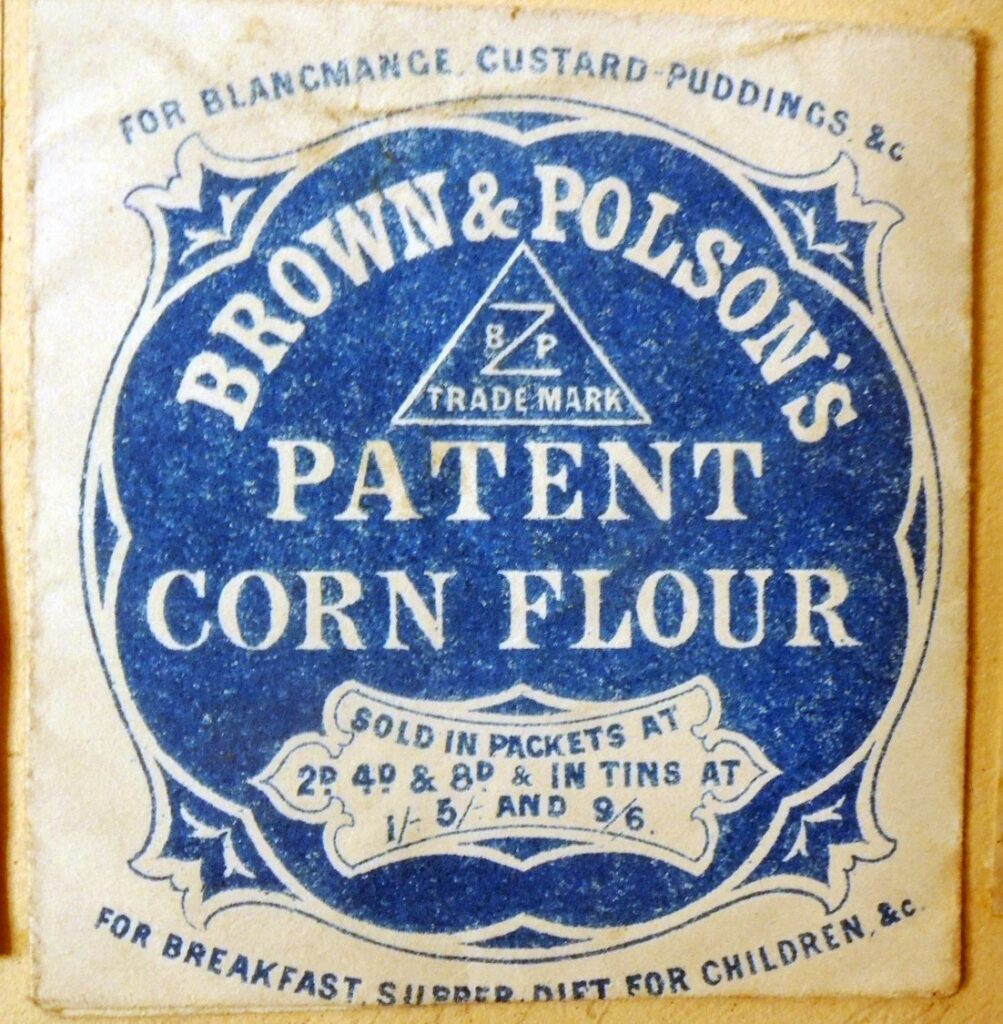

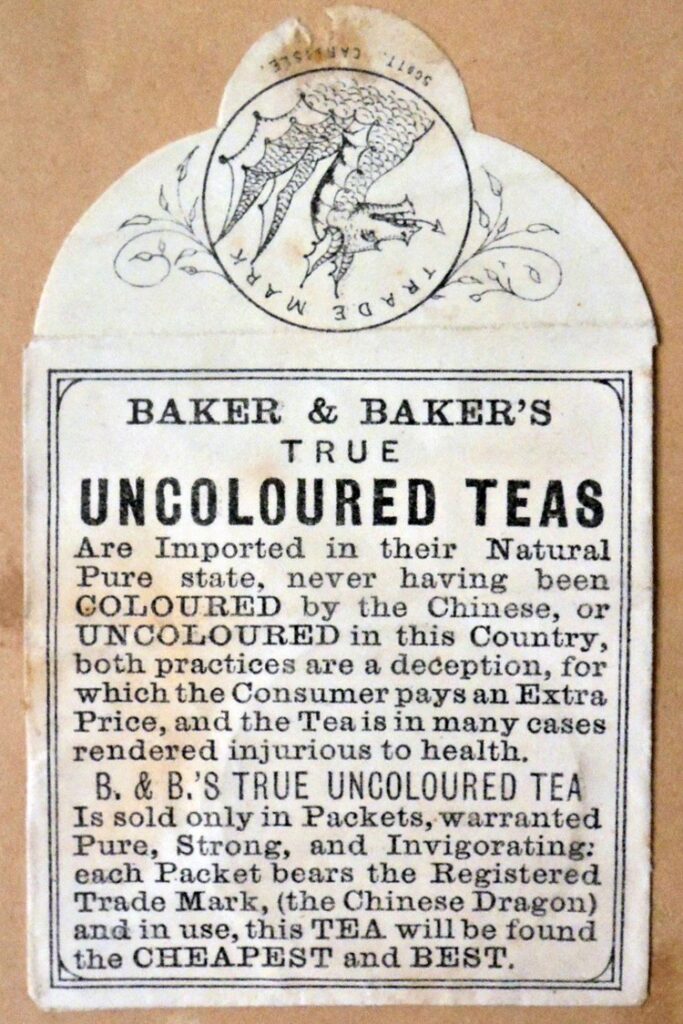

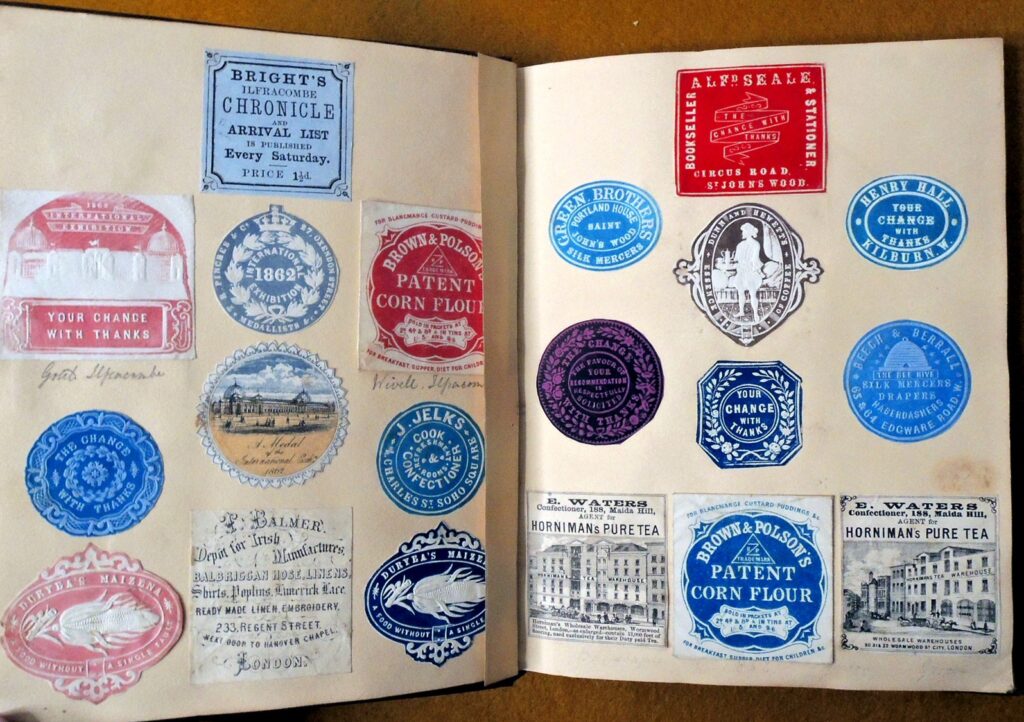

Princeton holds one of the best collections of change packets in the country, which will allow us to investigate the practices of early department stores and in particular, their advertising campaigns using these elaborately decorated little envelopes like miniature business cards to promote teas, biscuits, jellies, and even upcoming events.

Various devices would carry the sales slip and payment from a particular store counter to the mezzanine or back room where a staff of young women quickly noted the sale and returned the receipt with the customer’s change in that week’s envelope. This not only meant that the sales staff did not need to know arithmetic but it also protected the individual counters from theft. Here’s a quick peek at the pulleys and wires leading up to the cashier’s booth in Charlie Chaplin’s The Floorwalker (1916):

“In large retail stores where a great variety of goods are sold in one building, it has been found necessary to employ children to carry the money to the cashier and to take the goods to the packing and delivery departments. To get rid of the expense and inconvenience of having so many “cash” boys and girls in such stores, a number of inventions have been brought out, designed to act as substitutes. The most simple of these is a light iron rail suspended from the ceiling of the store over the counters. On this rail run small two-wheeled cars, each intended to carry a receptacle for money or parcels, or both. The salesman, on receiving the money for the goods, puts it in a car on the rail overhead, and it rolls by gravity down the rail to the cashier’s desk…”—“Shop Conveniences,” The Century 24 (October 1882): 956-58

Here’s a snippet with Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle causing trouble with the cash transport system in The Butcher Boy (1917):

Some “cash transport systems” continued into the 21st century. Check out this Canadian store:

Joyners store in Moose Jaw, SK, Canada had a cash cable system used since 1915 called the Lamson Cash Carrier System. You can watch the whole video and take a tour of the system including this behind the scenes look. Sadly the system was destroyed when a fire ravaged the building in 2004.

In the book Darkness Visible, William Golding wrote:

“Frankley’s was an ironmonger’s of character. After the convulsion of the First World War the place grew a spider’s web of wires along which money trundled in small, wooden jars. For people of all ages, from babies to pensioners, this was entrancing. Some assistant would fire the jar – clang! – from his counter and when the flying jar reached the till it would ring a bell – Dong! So the cashier would reach up, unscrew the jar, take out the money and inspect the bill, put in the change and fire the jar back – Clang! … Clang! All this took a great deal of time but was full of interest, like playing with model trains. But the use of the overhead railway had done two things. First it had accustomed the staff to moderate stillness and tranquility; and second, it had so habituated them to the overhead method of money sending that when one of these ancient gentlemen was offered a banknote he immediately gestured upwards with it as if to examine the watermark.”

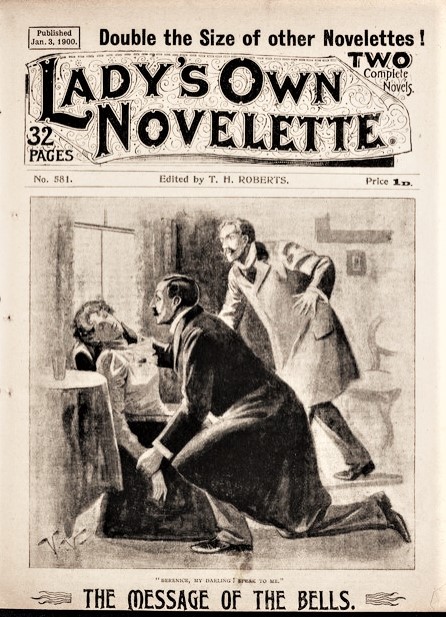

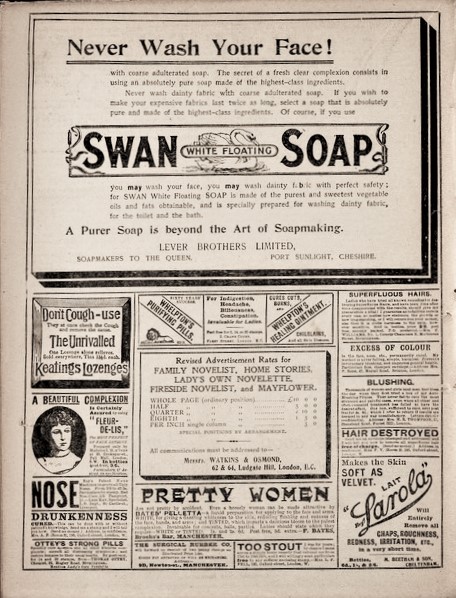

Near the end of the 19th century, dealers adjusted their prices to promote lower sounding numbers, using 99 cents rather than rounding up. The one cent change could be given in a penny or in pins or in low cost booklets, called a “farthing novelette.” These were so cheaply produced that the store would always come out ahead and make more money than giving out exact change. The back page was also another good opportunity for advertising.

Join us on January 18 for a fun look at the past and present, as we learn to better understand our current situation as it relates to what went before and what is to come in the future. Biscuits optional!!