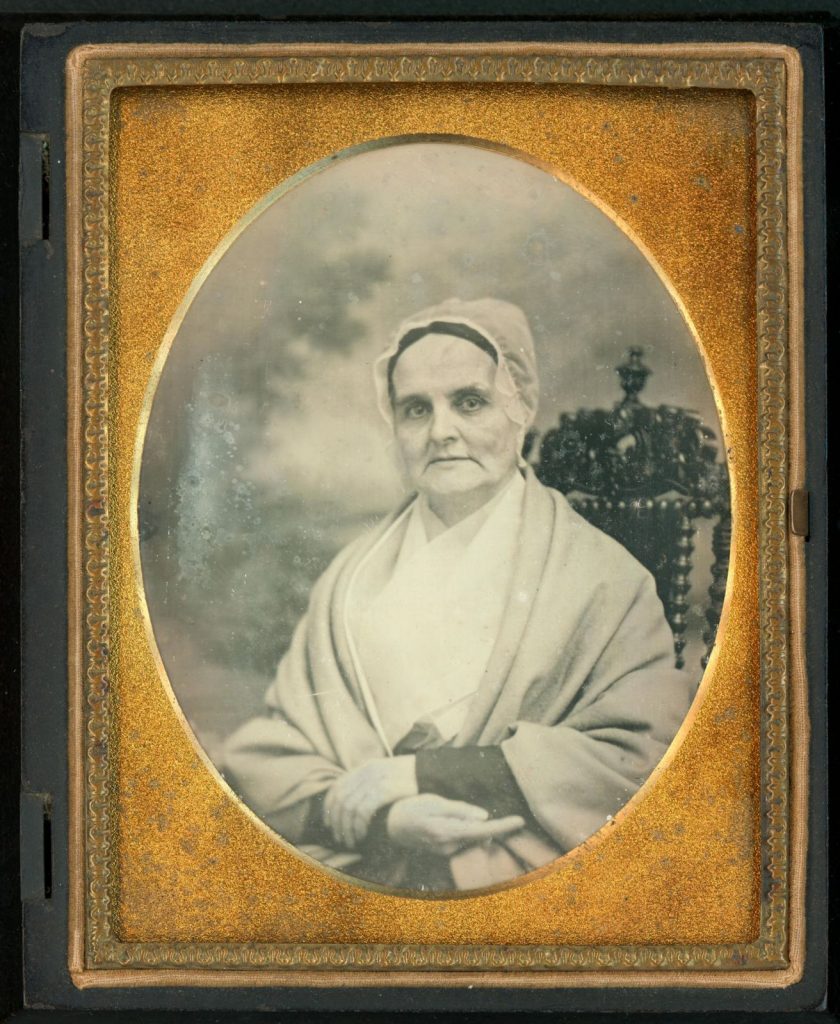

After Samuel Broadbent, Lucretia Mott, circa 1849. Quarter plate daguerreotype. Purchased thanks to funds from the Manuscript Collection and the Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2021- in process

After Samuel Broadbent, Lucretia Mott, circa 1849. Quarter plate daguerreotype. Purchased thanks to funds from the Manuscript Collection and the Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2021- in process

An abolitionist, Quaker, and fierce advocate for women’s rights, Lucretia (Lucy) Coffin Mott (1793-1880) believed that women and men should be treated equally and spent her adult life fighting for these causes. In 1833 she was among the women who established the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society and served as a delegate to the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. Although she was a powerful speaker, Mott was surprised to find she was not allowed to participate. Together with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and others, they organized the First Woman’s Rights Convention in 1848. Her address Discourse on Woman was delivered at the assembly buildings in Philadelphia on December 17, 1849 and published by T.B. Peterson in 1850 (Miriam Y. Holden Collection HQ1423 .M9). These are only a few of her many accomplishments, which continued until her death in 1880.

Notice the glare on the left side of this portrait. This might indicate that the daguerreotype now at Princeton is a copy daguerreotype, the shine a result of the reflective copperplate being rephotographed. If this is true, it tells us a great deal about the celebrity and admiration for Mott at the time, as well as the collecting habits that warranted additional portraits. See a few of her many portraits below.

We teach the daguerreotype as a ‘one-of-a-kind’ but there may have been an active business for daguerreotype reproductions. While the earlier daguerreotype with this image has not been located yet, we will list the portrait as ‘after Samuel Broadbent.’ The case has not been opened at Princeton (it just arrived) but the dealer notes “The hallmark, a hexamerous figure 40 was usually seen in the mid-to-late 1840s; also use of wax on the reverse copper side of the plate, as seen here, was generally ended by the advent of the 1850s. The edges of the original double elliptical mat that was used to frame the portrait can be seen on the naked plate.”

We teach the daguerreotype as a ‘one-of-a-kind’ but there may have been an active business for daguerreotype reproductions. While the earlier daguerreotype with this image has not been located yet, we will list the portrait as ‘after Samuel Broadbent.’ The case has not been opened at Princeton (it just arrived) but the dealer notes “The hallmark, a hexamerous figure 40 was usually seen in the mid-to-late 1840s; also use of wax on the reverse copper side of the plate, as seen here, was generally ended by the advent of the 1850s. The edges of the original double elliptical mat that was used to frame the portrait can be seen on the naked plate.”

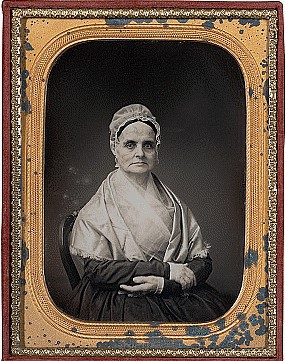

Samuel Broadbent (1810-1880), Lucretia Mott, ca. 1855. Quarter plate daguerreotype. Gift of Hallmark Cards, Inc. Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Samuel Broadbent (1810-1880), Lucretia Mott, ca. 1855. Quarter plate daguerreotype. Gift of Hallmark Cards, Inc. Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Even without this mark, Samuel Broadbent Jr. (1810-1880/01) is a good guess given his other portraits and similar painted backdrops. A different daguerreotype portrait of Mott was made by Broadbent around 1855 [above] and a CDV published by Broadbent and Phillips (Henry C. Phillips) around 1865. Sarah Weatherwax has given us a record of his studios:

Working primarily as a portrait photographer for almost four decades, Broadbent entered into a number of different partnerships, including with female daguerreotypist Sally [Sarah] Garrett Hewes, Henry C. Phillips, William Curtis Taylor, and fellow painter Frederick A. Wenderoth. He worked in a variety of photographic mediums and produced images utilizing a number of different processes. His daguerreotypes frequently employed a painted landscape background or centered the sitter within a window frame adorned with large leafy vines along one side. In addition to daguerreotypes, the Broadbent studio also produced ambrotypes and tintypes and successfully made the transition to paper photography. After Samuel Broadbent’s death in 1880, two of his sons continued his photography business until 1905. A Broadbent photography studio remained in Philadelphia until 1920.”–Sarah J. Weatherwax, Curator of Prints and Photographs, The Library Company of Philadelphia, 2013.

William Henry Furness (1802-1896), Lucretia Mott, 1858. Oil on canvas. Swarthmore College Friends Historical Library

William Henry Furness (1802-1896), Lucretia Mott, 1858. Oil on canvas. Swarthmore College Friends Historical Library

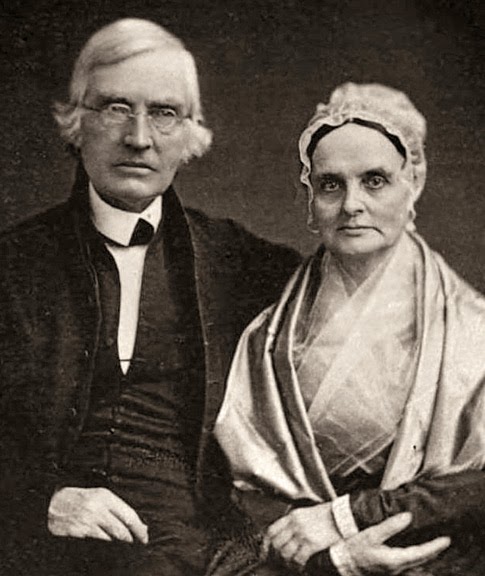

Reproduction of a daguerreotype portrait of Lucretia and James Mott sitting together, original photograph by William Langenheim, 1842. Location of original unknown.

Reproduction of a daguerreotype portrait of Lucretia and James Mott sitting together, original photograph by William Langenheim, 1842. Location of original unknown.

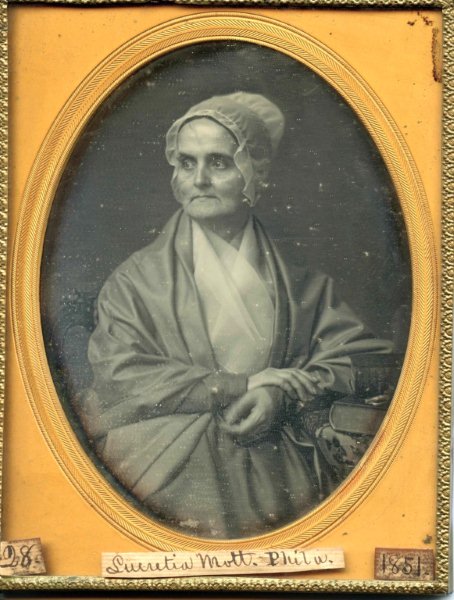

Marcus Aurelius Root, Lucretia Coffin Mott, 1851. Half-plate daguerreotype. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Marcus Aurelius Root, Lucretia Coffin Mott, 1851. Half-plate daguerreotype. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.