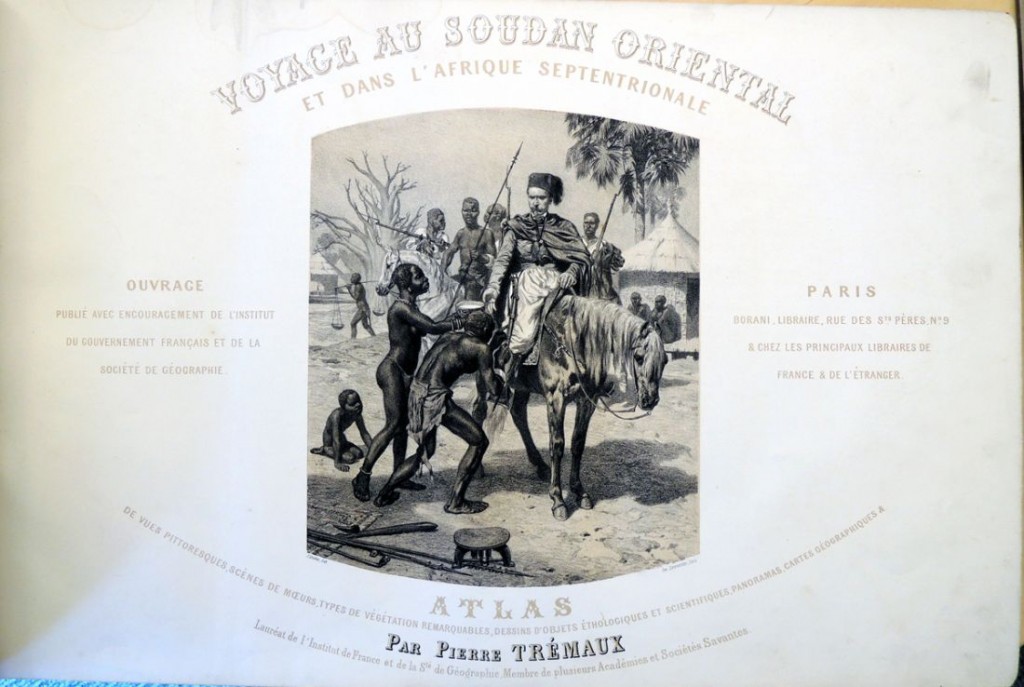

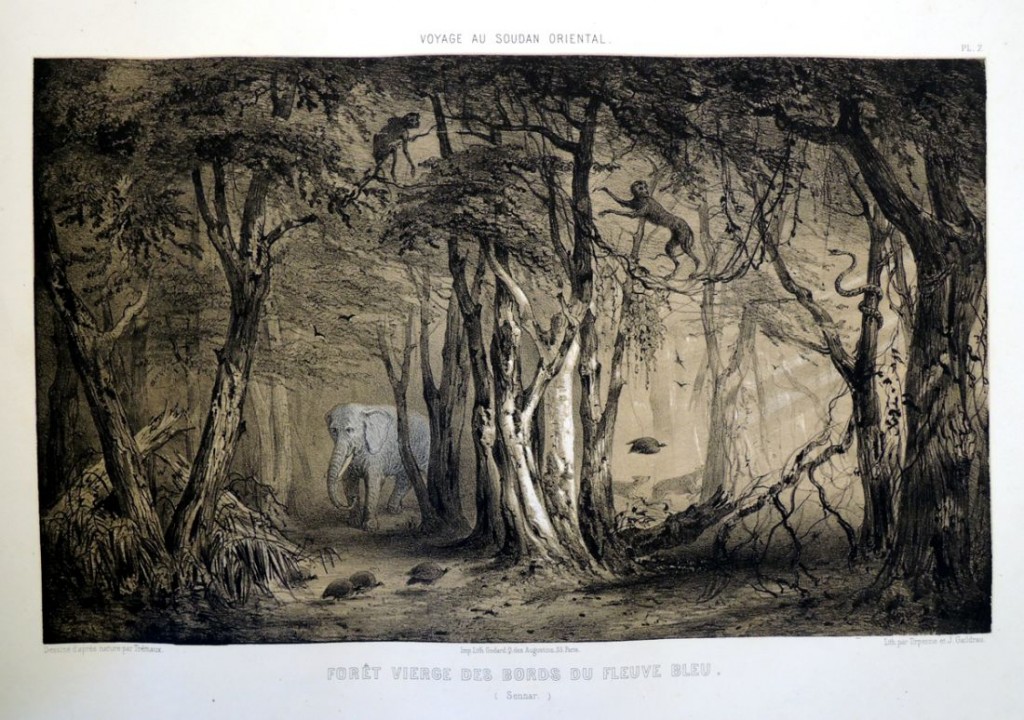

Pierre Trémaux, Voyages au Soudan oriental et dans l’Afrique septentrionale, exécutés de 1847 à 1854: comprenant une exploration dans l’Algérie, les régences de Tunis et de Tripoli, l’Égypte, la Nubie, les déserts, l’île de Méroé, le Sennar, le Fa-Zoglo, et dans les contrées inconnues de la Nigritie (Paris: Borrani, [1852-1858]). Purchased with funds provided by the Friends of the Princeton University Library, Rare Book Collection, and Graphic Arts Collection. GAX 2013- in process

Pierre Trémaux is not well known but holds a place in the history of illustrated books for publishing one of the first photographically illustrated travelogues. North Africa, Egypt in particular, was one of the earliest destinations for European photographers and one of most frequently represented subjects. By autumn 1839 the daguerreotypist Frédéric Goupil-Fesquet was in Egypt, together with the painter Horace Vernet, gathering material for their travelogue Voyage d’Horace Vernet en Orient (1843). The first extensive survey was completed by Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey in 1842-43 covering Asia Minor, Syria, Egypt, Palestine, and Greece. None of the early publications of these trips included actual photographs.

As an architect interested in urban planning, Pierre Trémaux traveled to Algeria, Tunisia, Upper Egypt, Eastern Sudan and Ethiopia beginning in 1847 (preceding Maxime Du Camp by two years and Félix Teynard by four years). At first, he made drawings and daguerreotypes as the basis for lithographic illustrations but wished to publish a more authentic record of the African culture. On the second expedition, he brought a camera and chemistry to create calotypes of the people, buildings, and landscape of in Libya, Egypt, Asia Minor, Tunisia, Syria, and Greece. A third and final expedition included both photographs and sketches. Trémaux published an account of his travels in parts from 1852 to 1858.

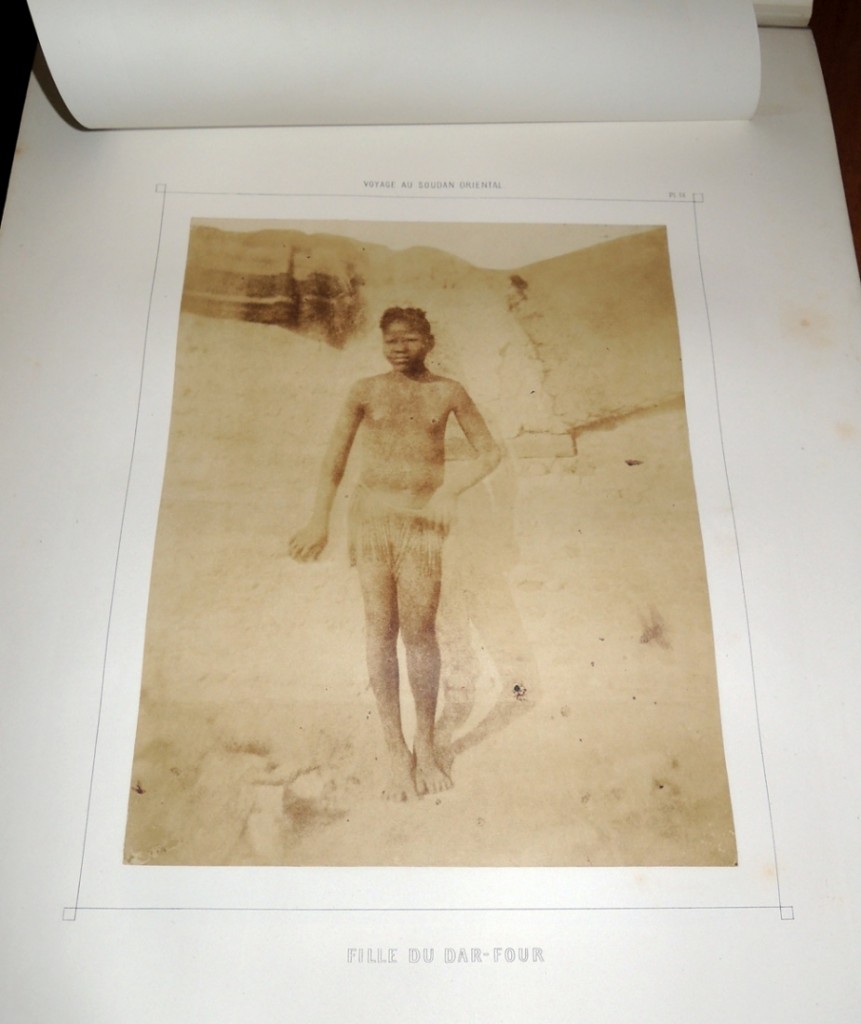

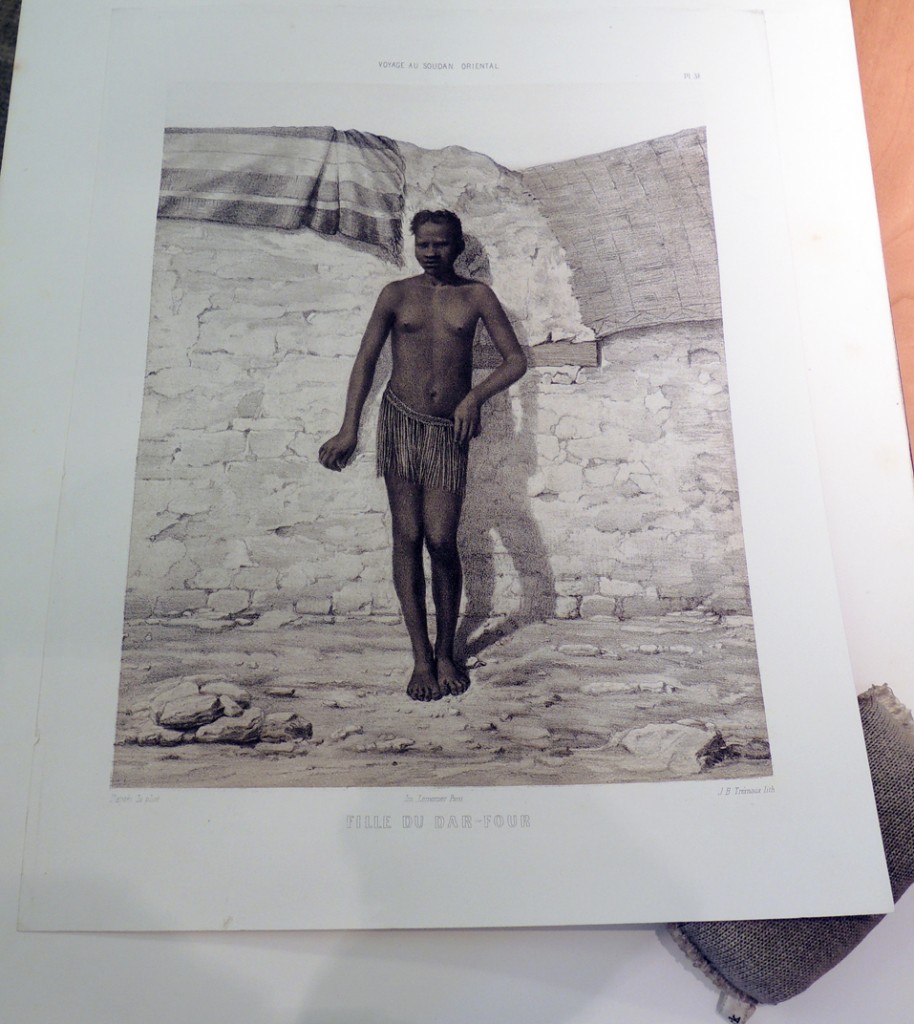

It is with the publication of Voyage au Soudan oriental et dans l’Afrique septentrionale exécutés en 1847 à 1854 that the photographically illustrated travel book begins. In this folio, Trémaux made paper photographs and then, for each one also had lithographs created. The two are bound together so the reader has the authenticity of the photograph–thought to be a truthful document–along with the more robust image of the drawn lithograph. This took a tremendous amount to time and money but demonstrations the importance given to the publication at that time.

The book is included in the catalogue for the Grolier exhibition The Truthful Lens, where it is noted that the artist signed his plates, “Trémaux lithophot. Precédé Poitevin,” referring to Alphonse-Louis Poitevin, a French engineer who is credited with developing photomechanical processes such as photolithography in the 1850s. The entry goes on to mention that copies vary greatly, such as the one at The Avery Library, Columbia University, which has 58 photolithographs, but no calotypes.

Special thanks to the Friend of the Princeton University Library and Steve Ferguson, Rare Book Division, for making this acquisition possible.