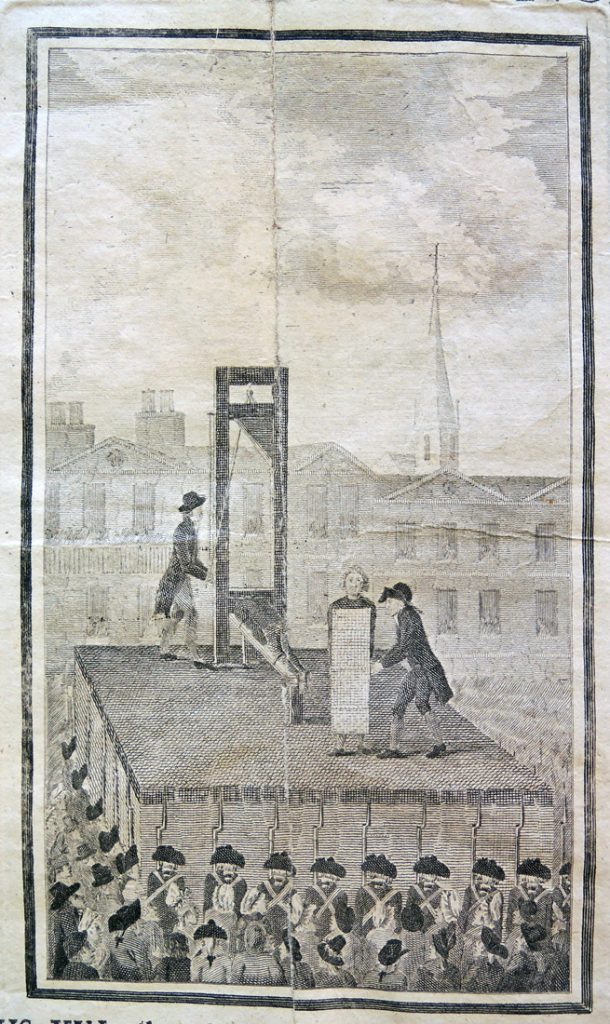

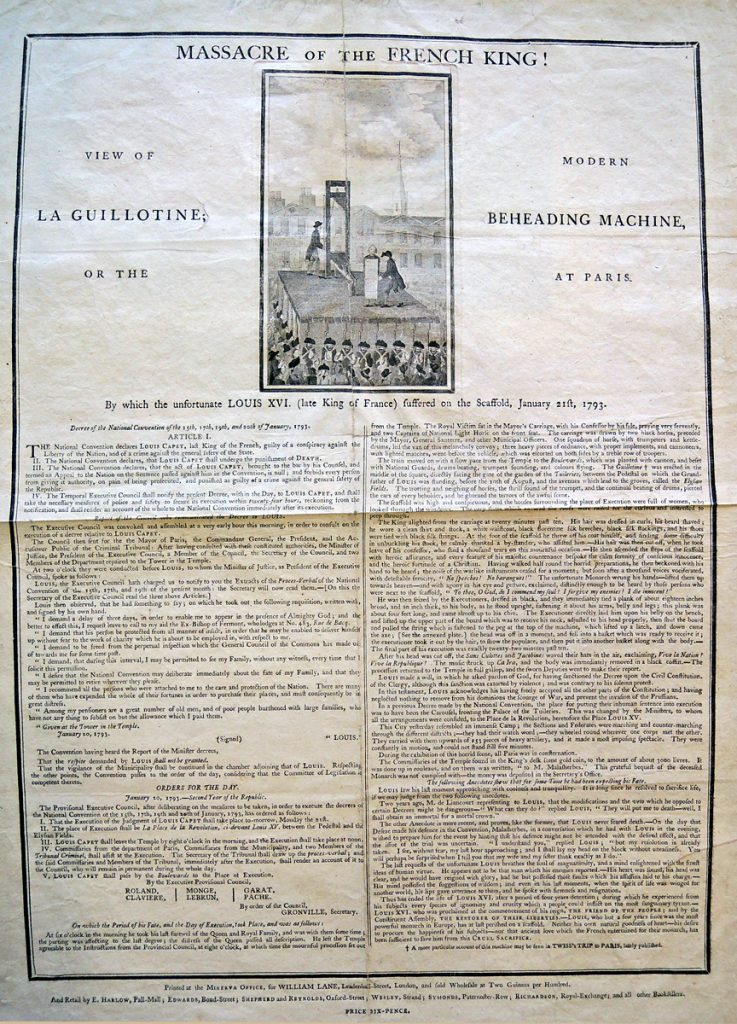

In this engraving, one man is already face down in the guillotine and a second, being tied to a board, will be next. Neither is Louis XVI.

In this engraving, one man is already face down in the guillotine and a second, being tied to a board, will be next. Neither is Louis XVI.

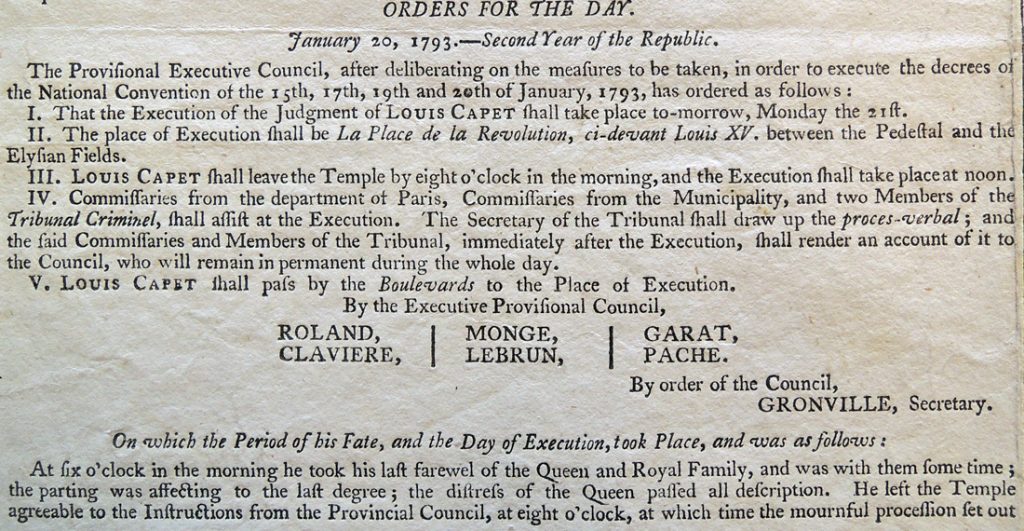

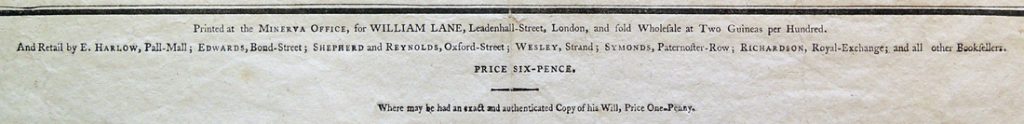

Massacre of the French King! View of La Guillotine; or the Modern Beheading Machine, at Paris. By which the unfortunate Louis XVI (late King of France) suffered on the Scaffold, January 21st, 1793. Engraving and letterpress broadside. London: printed at the Minerva Office, for William Lane, and retail by E[Lizabeth] Harlow, Pall-Mall; Edwards, Bond-Street; Shepherd and Reynolds, Oxford-Street; . . . and all other Booksellers. Where may be had an exact and authenticated copy of his Will, Prince One-Pence, 1793. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2016- in process

“In London, the charismatic William Lane (ca. 1745-1814)) founded the Minerva Press in 1790, issuing remarkable numbers of sensational novels until he was succeeded upon his death by his partner A. K. Newman, who continued the business (although he gradually dropped the ‘Minerva Press’ name) through the 1820s. During the 1790s Minerva published fully a third of all the novels produced in London.” –Stuart Curran, The Cambridge Companion to British Romanticism (Cambridge University Press, 2010)

“By 1791 Lane employed a workforce of thirty and had four printing presses . . . Most were formulaic Gothic ‘German’ romances, produced in editions of 500 or 750 and never reprinted. ‘Minerva press’ novel became a common term to describe a particular type of light society romance or thriller, much condemned in conduct literature.” –William St. Clair, The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period (Cambridge University Press, 2004)

“When William Lane . . . published his broadside account of the execution on January 29, he priced it at sixpence, with a discount for bulk purchases of one hundred; a few days later he halved the original price, and offered a still more generous discount to those willing to act as agents to distribute the sheet, expressing the hope that it would be circulated ‘in every village throughout the three kingdoms.’

In a long advertisement announcing these reductions, Lane described his wish that ‘this horrid and unjust sacrifice . . . should be known to all classes of people, and in particular to the honest and industrious Artisan and manufacturer, who might be deluded by the false and specious pretences of artful and designing persons.’” –Kevin Sharpe and Steven N. Zwicker, Refiguring Revolutions: Aesthetics and Politics from the English Revolution to the Romantic Revolution (University of California Press, 1998)