Nicolas and Alexis Kugel are the fifth generation of a family of antiques dealers founded in Russia at the end of the 18th century by their great-great-grandfather Elie Kugel, a collector of clocks and watches. In 1985, the Kugels took over the family business and in 2004, relocated the gallery to Hôtel Collot, 25 quai Anatole France, built in 1840 by Louis Visconti for Jean-Pierre Collot, director of La Monnaie (the French Mint).

Nicolas and Alexis Kugel are the fifth generation of a family of antiques dealers founded in Russia at the end of the 18th century by their great-great-grandfather Elie Kugel, a collector of clocks and watches. In 1985, the Kugels took over the family business and in 2004, relocated the gallery to Hôtel Collot, 25 quai Anatole France, built in 1840 by Louis Visconti for Jean-Pierre Collot, director of La Monnaie (the French Mint).

Galerie J. Kugel is unique in its specialties and the eclecticism of the works of art it offers, including silver, sculpture, Kunstkammer objects, automatons, scientific instruments, and much more.

While visiting Galerie J. Kugel, we had the pleasure of viewing some of the unique treasures featured in Alexis Kugel’s most recent catalogue A Mechanical Bestiary: Automaton Clocks of the Renaissance, 1580-1640 (Marquand (SA) Oversize NK7495.G4 K8413 2016q).

Some pieces came from the Kugel family collection, which Mr. Kugel recalls playing with as a child: “I probably broke one or two, forcing the needle so it would animate,” he told Jake Cigainerosept of the New York Times.

Cigainerosept notes that the technology for automaton clocks dates to Heron of Alexandria, the ancient Greek mathematician who wrote extensively about mechanics. Their popularity surged during the Renaissance, when many were made in Augsburg, Germany, the artistic center of Bavaria at the time.

There is a pug dog whose eyes spin and tail wags; a monkey that beats his drum; and an elephant with dancing soldiers. “If you couldn’t afford a real elephant or lion for your menagerie,” noted Mr. Kugel, “then you could compromise with one of these.”

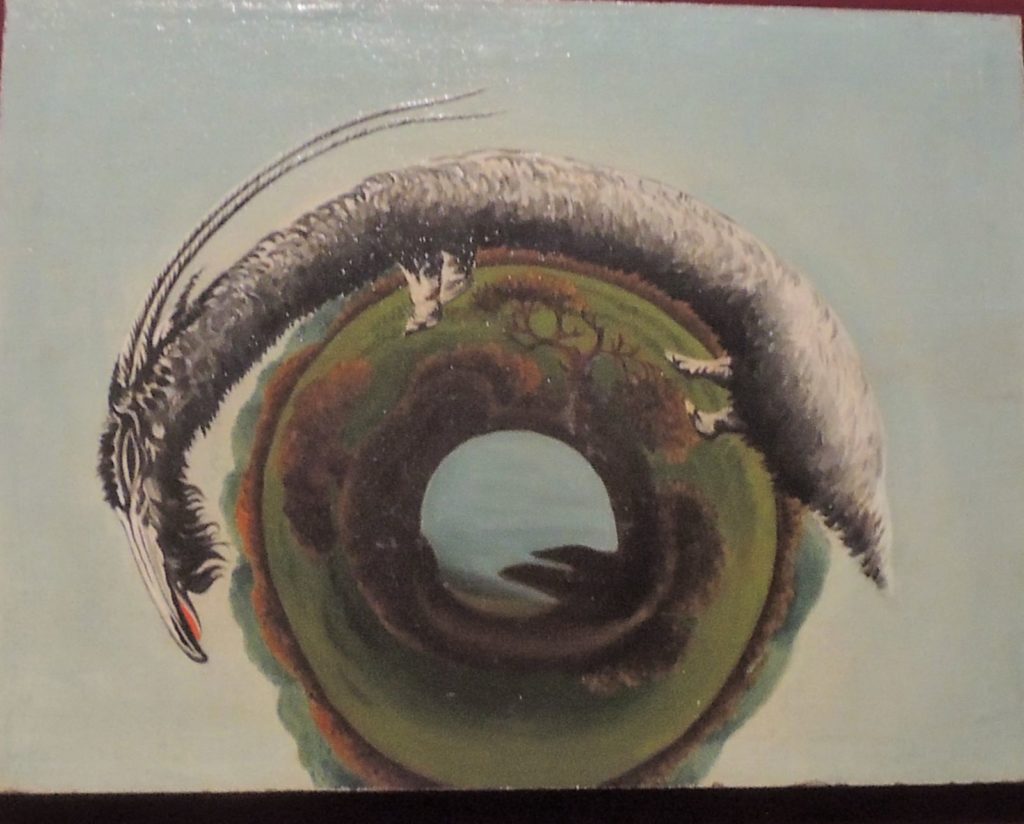

In another remarkable room are 18th-century anamorphic panel paintings, meant to be viewed in the reflection of a mirrored cylinder. We have several anamorphic prints in Princeton’s graphic arts collection, although not as rare or historic. https://graphicarts.princeton.edu/2015/03/25/anamorphic-images/