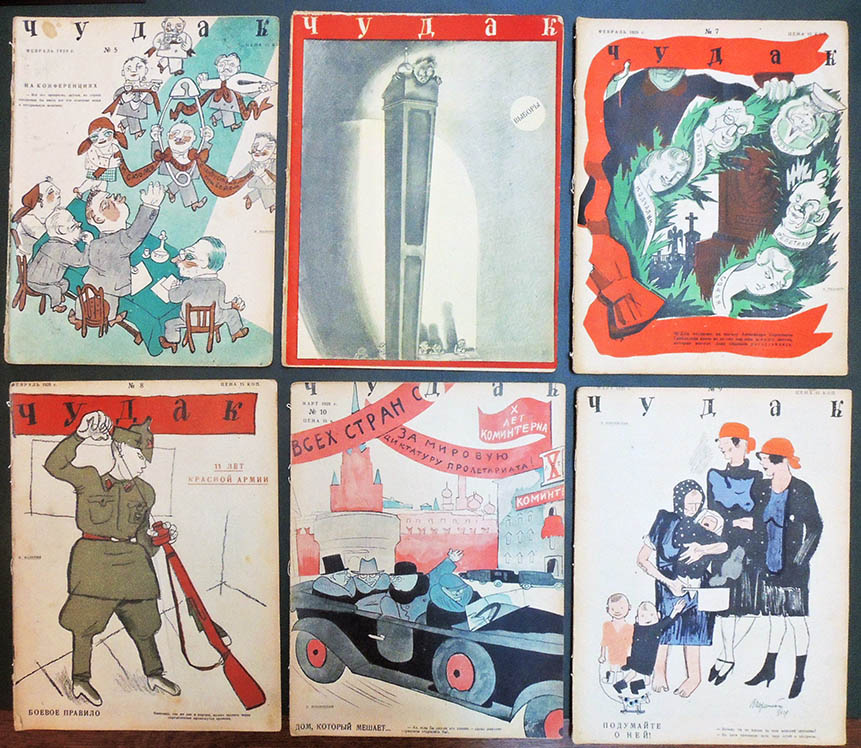

Chudak = The Oddball or Poor Guy (Moscow: Ogonek, 1928-1929). Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2019 in process. No. 1 (1928), nos. 2-50 (1929); 23.0 x 30.0 cm; each issue pp. 16.

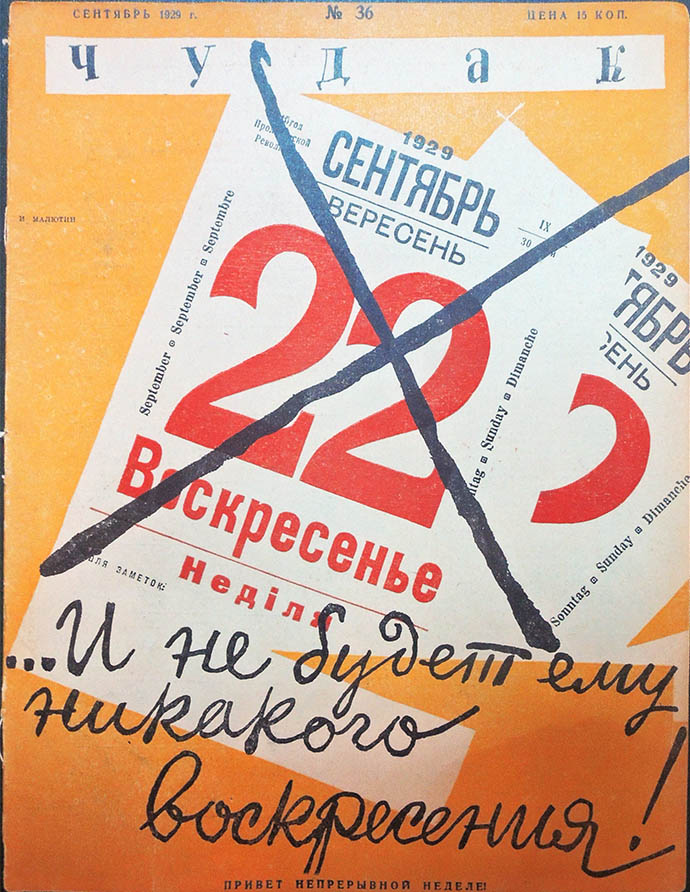

Together with Thomas Keenan, Slavic East European and Eurasian Studies Librarian, the Graphic Arts collection recently acquired 50 of 56 rare issues of the satirical Soviet magazine Chudak (The Oddball), including the banned and retracted issue no. 36. No other library has these physical volumes, with the exception of two issues at Cambridge University. Issue no. 36 is not held at either the Russian State Library or the Russian National Library.

Together with Thomas Keenan, Slavic East European and Eurasian Studies Librarian, the Graphic Arts collection recently acquired 50 of 56 rare issues of the satirical Soviet magazine Chudak (The Oddball), including the banned and retracted issue no. 36. No other library has these physical volumes, with the exception of two issues at Cambridge University. Issue no. 36 is not held at either the Russian State Library or the Russian National Library.

Given the lack of information on this ephemeral publication, our dealer’s note is quoted at length:

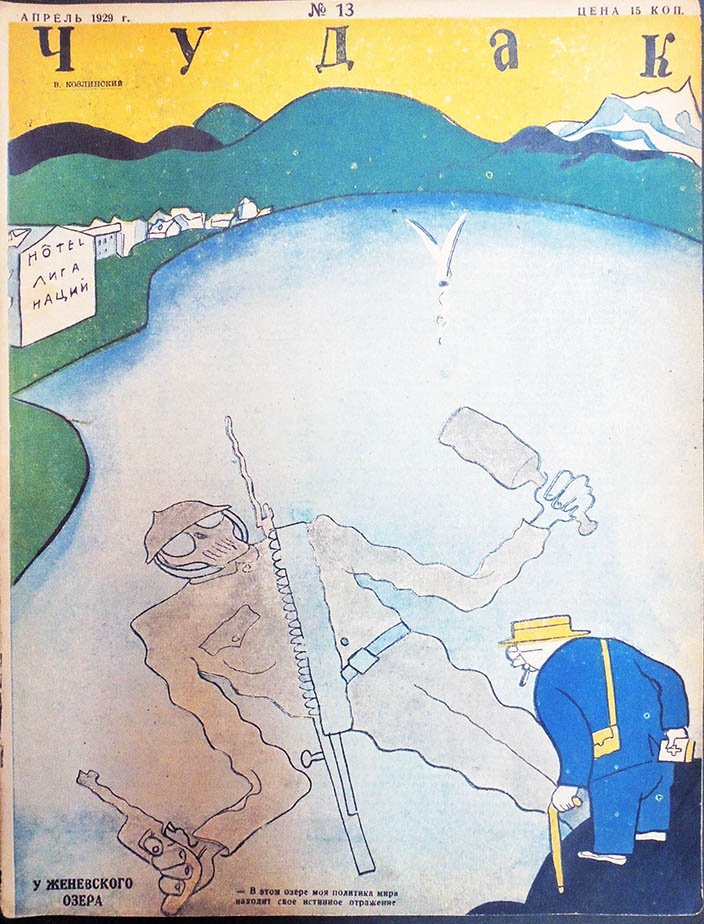

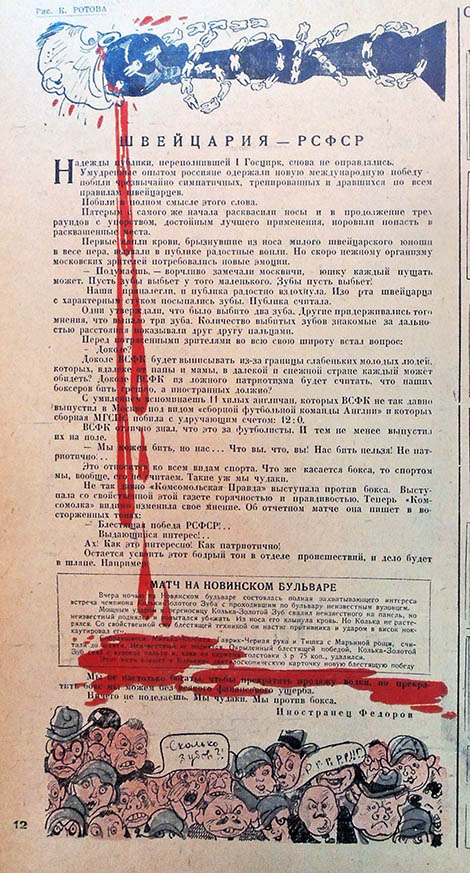

“During its brief and troubled, yet brilliant existence, Chudak brought together the Soviet Union’s sharpest satirical talents, both writers and caricaturists. Its literary staff and contributors included the team Ilf and Petrov, Kataev, Mayakovsky, Zoshchenko, Demyan Bedny, Gorky, Olesha, Svetlov, Arkhangelsky, Volbin, Zabolotsky, Ryklyin, Tvardovsky, and Utkin. Among its illustrators were Deni, Efimov, Bodraty, Kozlinsky, Ratov, Radlov, Malyutin, Deyneka, and the Kukryniksy.

This eminent ensemble was led by editor-in-chief Mikhail Koltsov, one of the foremost Soviet journalists of the 1930s and the inspiration for the character Karkov in Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls. Like its Leningrad-based contemporary Revizor, Chudak was born of the Central Committee’s April 1927 decree “On Satirical and Humorous Magazines,” which aimed to rein in rogue publications by replacing staff, merging enterprises, or shutting down papers outright.

As a consequence of this campaign, Koltsov inherited editorship of the satirical magazine Smekhach (February 1924–December 1928), which had seen its staff and readership gutted. Together with Ilf and Petrov, Vasily Reginin, Grigory Rylkin, and the others, Koltsov envisioned a complete rebranding of the magazine. He described this new publication in a letter to Maxim Gorky, who would pledge his support and contribute to the first issue:

As a consequence of this campaign, Koltsov inherited editorship of the satirical magazine Smekhach (February 1924–December 1928), which had seen its staff and readership gutted. Together with Ilf and Petrov, Vasily Reginin, Grigory Rylkin, and the others, Koltsov envisioned a complete rebranding of the magazine. He described this new publication in a letter to Maxim Gorky, who would pledge his support and contribute to the first issue:

“We have gathered a good group of writers and artists, and we have decided–whatever it takes–to give our magazine a new identity, completely breaking with faded satirical traditions. We are convinced that, contrary to all the yammering about ’the official seal’, a good satirical journal can exist in the USSR, excoriating bureaucratism, sycophancy, philistinism, duplicity, and active and passive sabotage.

The title Chudak did not come about by accident. We picked up this word as if it were the gauntlet that the average man bewilderedly and aloofly throws when he sees a deviation from himself, from the safe path: “He believes in Socialist Construction? There’s an Oddball!” “He’s subscribed to a bond drive? That’s an Oddball” “He thinks nothing of a good salary? What an Oddball!” We paint this disparaging name in romantic and vivacious colors. Chudak is no voice of acrimonious satire; it is sanguine, healthy, and happy. Neither is Chudak a high-toned abuser; to the contrary, it scrappily defends the many unjustly abused and willingly turns its bristling quill against the juries of skeptics and whiners.

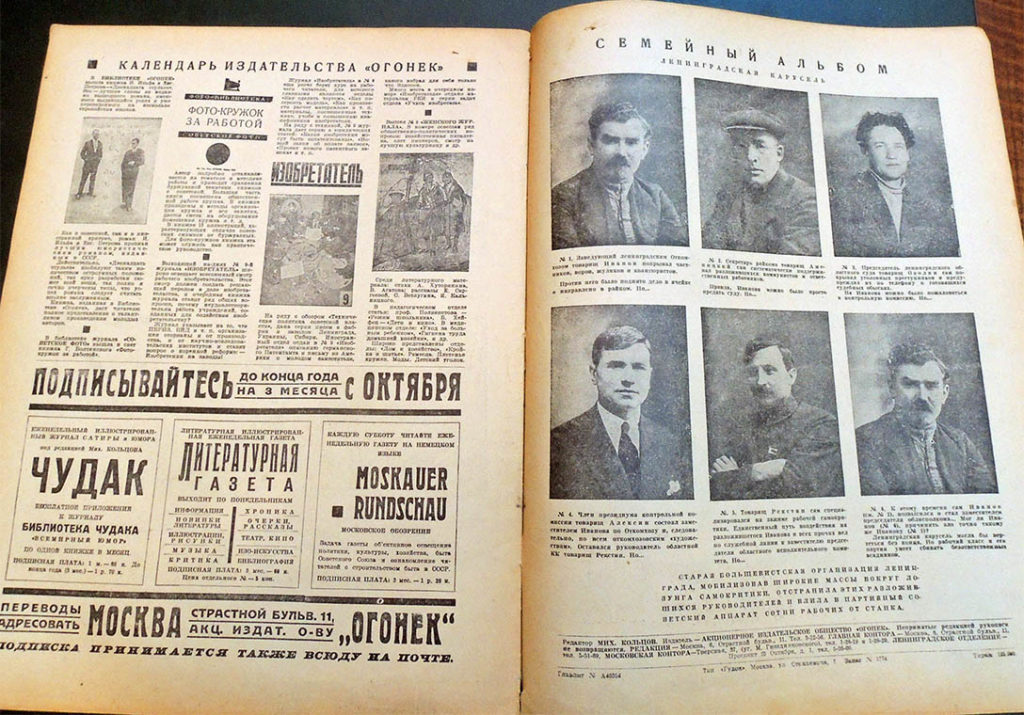

Chudak was considered bolder and more literary than its competitors, corresponding with caliber of its contributors. However, it rode the line of political acceptability and eventually overstepped its bounds. The 36th issue (September 1929) incited the Party’s wrath by lampooning the “Leningrad Carousel” of officials in charge of an anti-Trotskyist campaign. This triggered the Central Committee decree of September 20, 1929, “On the Magazine Chudak,” which decried the “blatantly anti-Soviet character” of the material and removed Koltsov from his post. It further “charge[d] the OGPU to urgently investigate the matter of the insertion of these materials into the magazine Chudak and take measures to retract issue No. 36 of the magazine.

Chudak was considered bolder and more literary than its competitors, corresponding with caliber of its contributors. However, it rode the line of political acceptability and eventually overstepped its bounds. The 36th issue (September 1929) incited the Party’s wrath by lampooning the “Leningrad Carousel” of officials in charge of an anti-Trotskyist campaign. This triggered the Central Committee decree of September 20, 1929, “On the Magazine Chudak,” which decried the “blatantly anti-Soviet character” of the material and removed Koltsov from his post. It further “charge[d] the OGPU to urgently investigate the matter of the insertion of these materials into the magazine Chudak and take measures to retract issue No. 36 of the magazine.

Koltsov was forced to issue a groveling apology (not without finger-pointing; he alleged that he had succumbed to hysteria propagated by the general press). While he was reinstated a month later due to the intervention of Kliment Voroshilov and Lazar Kaganovich, this was too little too late. The rival, state sponsored satirical magazine Krokodil had used the intervening time to organize a hostile takeover. Chudak was forcibly merged with Krokodil in February 1930.

Chudak’s literary legacy includes poems by Mayakovsky (“Govoriat” in No. 3, “Mrachnoe o iumoristakh” in No. 5, “Chto takoe” in No. 9, and others) and more than 70 pieces by Ilf and Petrov under their own names or a variety of pseudonyms, such as “F. Tolstoyevsky.” Many unsigned works have also been attributed to the duo.

Chudak’s literary legacy includes poems by Mayakovsky (“Govoriat” in No. 3, “Mrachnoe o iumoristakh” in No. 5, “Chto takoe” in No. 9, and others) and more than 70 pieces by Ilf and Petrov under their own names or a variety of pseudonyms, such as “F. Tolstoyevsky.” Many unsigned works have also been attributed to the duo.

However, their most important writings were the unfinished, serialized novellas Neobyknovennye istorii iz zhizni goroda Kolokolamska (Unusual Tales from the Life of the City Kolokalamsk) and Tysiacha i odin den’, ili Novaia Shakherezada (A Thousand and One Days, or the New Scheherazade), both of which foreshadowed their classic book Zolotoi telionok (The Little Golden Calf).

See additional information on Koltsov: https://www.economist.com/books-and-arts/2008/10/16/a-call-to-arms