Charles Mottram (1817-1876) after Joseph Ames (1816-1872), The Last Days of Webster at Marshfield: to the Family and Friends of the Late Daniel Webster, This Plate Representing a Scene During His Last Days at Marshfield, Is Most Respectfully Dedicated by the Publishers, 1858. Etching and engraving. Published by Smith & Parmalee, 59 Beekman Street, New York, NY.

Charles Mottram (1817-1876) after Joseph Ames (1816-1872), The Last Days of Webster at Marshfield: to the Family and Friends of the Late Daniel Webster, This Plate Representing a Scene During His Last Days at Marshfield, Is Most Respectfully Dedicated by the Publishers, 1858. Etching and engraving. Published by Smith & Parmalee, 59 Beekman Street, New York, NY.

In 2002, the Musée d’Orsay held an exhibition of Last Portraits. “The purpose of the exhibition is to evoke a practice of the past: portraying a deceased person, on their deathbed or in their coffin. This ‘last portrait’ – death mask, painting, drawing or photograph – remained in the narrow circle of relatives and friends, but, in the case of famous personalities, it could be widely circulated in public. This practice, extremely common in Western countries in the nineteenth century and until the first half of the twentieth century, is today fast disappearing, or at least it remains strictly within the boundaries of the private sphere.”

The last portrait of Daniel Webster (1782-1852), a Whig senator from Massachusetts, was not included in their show but was the subject of a recent reference question. Webster, who Sydney Smith once called “a steam-engine in trousers,” died at his home in Marshfield in 1852 after falling off his horse.

Who are the others in this scene? Joseph Alexander Ames (1816-1872); Daniel Webster (1782-1852); Charles Henry Thomas; Jacob Le Roy; Edward Curtis; Caroline Bayard Le Roy Webster (1797-1882); Mrs. James Paige; James W. Paige; George Ashmun (1804-1870); Rufus Choate (1799-1859); Peter Harvey (1810-1879); Col. Fletcher Webster, 1819-1862; Caroline L. Appleton; Daniel Webster, Jr.; Mrs. Fletcher Webster; Caroline Webster (1845-1884); J. Mason Warren; Unidentified Woman; John Taylor; Porter Wright.

“The whole household were now again in the room, calmly awaiting the moment when he would be released from pain. …It was past midnight, when, awaking from one of the slumbers that he had at intervals, he seemed not to know whether he had not already passed from his earthly existence. He made a strong effort to ascertain what the consciousness that he could still perceive actually was, and then uttered those well-known words, “I still live!” as if he had satisfied himself of the fact that he was striving to know. They were his last coherent utterance. …At twenty-three minutes before three o’clock, his breathing ceased; the features settled into a superb repose; and Dr. Jeffries, who still held the pulse, after waiting for a few seconds, gently laid down the arm, and, amid a breathless silence, pronounced the single word ‘Dead.’ –“The Death-bed of Daniel Webster,” Appletons’ Journal [Volume 3, Issue 49, Mar 5, 1870; pp. 273-275].

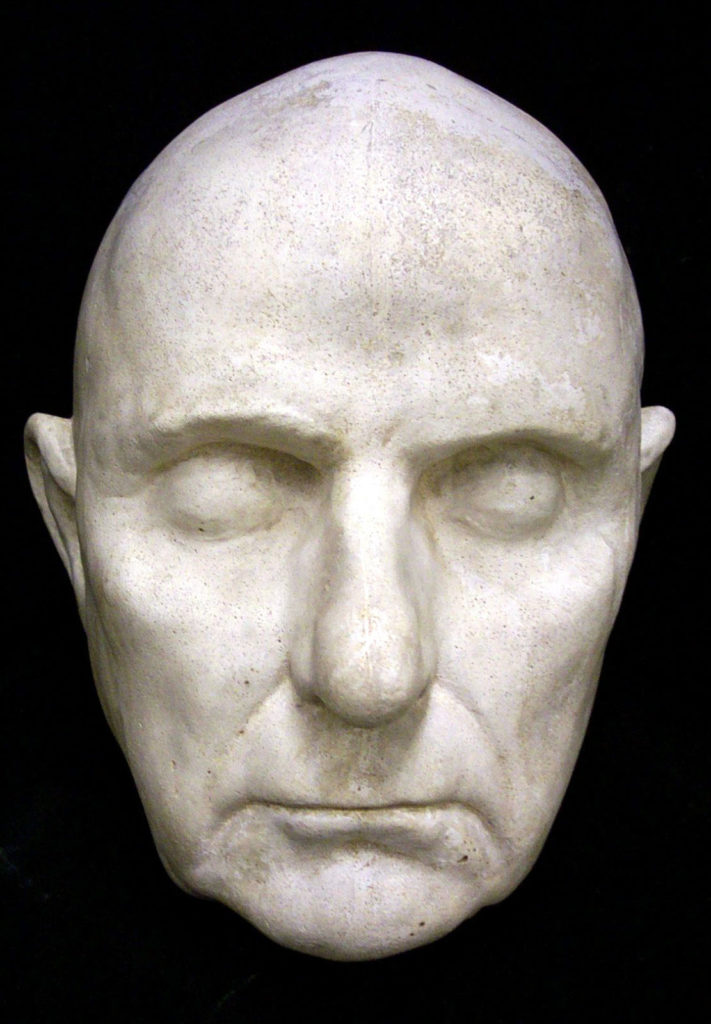

Princeton is fortunate to also hold a life mask [left] of Webster’s face taken in Washington D.C. by Clark Mills (1810-1883) in 1849.

Princeton is fortunate to also hold a life mask [left] of Webster’s face taken in Washington D.C. by Clark Mills (1810-1883) in 1849.

“Clark Mills … developed a new technique for creating life masks that was quicker and cheaper than the existing method and as a result received many commissions for sculptures. In 1847, Mills traveled to Washington to study the statuary in the Capitol. He was selected by Congress to create an equestrian statue of President Andrew Jackson, winning the commission over the artist Hiram Powers. This piece was the first monumental equestrian statue in the country to be cast in bronze….”—Smithsonian American Art Museum

Laurence Hutton wrote “I cannot to this day understand how Clark Mills managed to make moulds from life of the entire head of Webster and of that of Calhoun, each so distinct and so near to nature, without leaving in the casts some traces of the hair they wore. Their faces were smooth shaven, but they were both far from being bald. The occiput must have been carefully and closely covered with something which left no mark; but what that something was I cannot determine. Each cast is signed by the artist and dated — Calhoun’s in 1844, Webster’s in 1849,—and that clearly enough establishes their identity. … both he and Webster—the phrenologists tell us—had unusually large heads; and we need no phrenologists to tell us that there was a good deal in them.” Laurence Hutton, Talks in a library with Laurence Hutton (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1905)

Some of the many other deathbed scenes include:

Junius Brutus Stearns (1810-1885), Washington on his Deathbed, 1851. Oil on canvas. Dayton Art Institute, Ohio.

Junius Brutus Stearns (1810-1885), Washington on his Deathbed, 1851. Oil on canvas. Dayton Art Institute, Ohio.

Jacques Louis David (1748–1825), Death of Socrates, 1787. Oil on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1931

Jacques Louis David (1748–1825), Death of Socrates, 1787. Oil on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1931

Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret (1782-1863), Honors Rendered to Raphael on His Deathbed, 1806. Oil on canvas. Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, Ohio.

Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret (1782-1863), Honors Rendered to Raphael on His Deathbed, 1806. Oil on canvas. Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, Ohio.

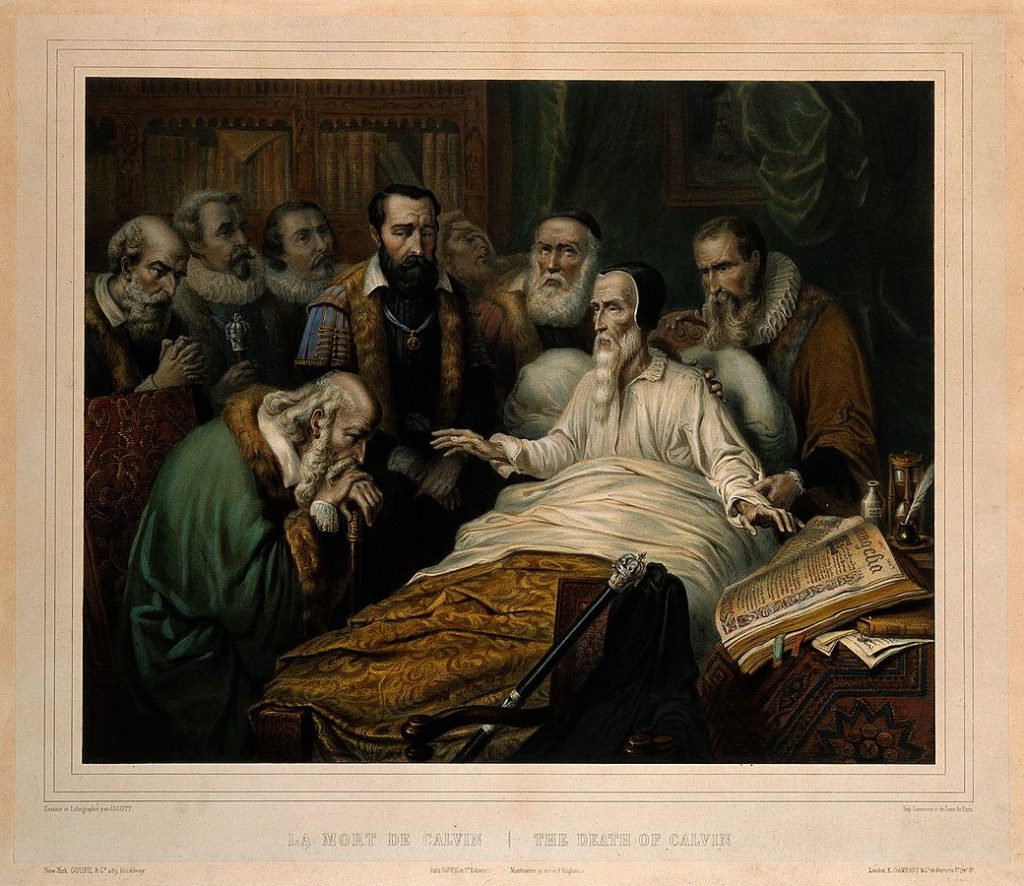

William L. Walton (1796-1872) after Oakley, John Calvin on his deathbed, with members of the Church in attendance, ca. 1865. Lithograph. Wellcome Trust, London.

William L. Walton (1796-1872) after Oakley, John Calvin on his deathbed, with members of the Church in attendance, ca. 1865. Lithograph. Wellcome Trust, London.

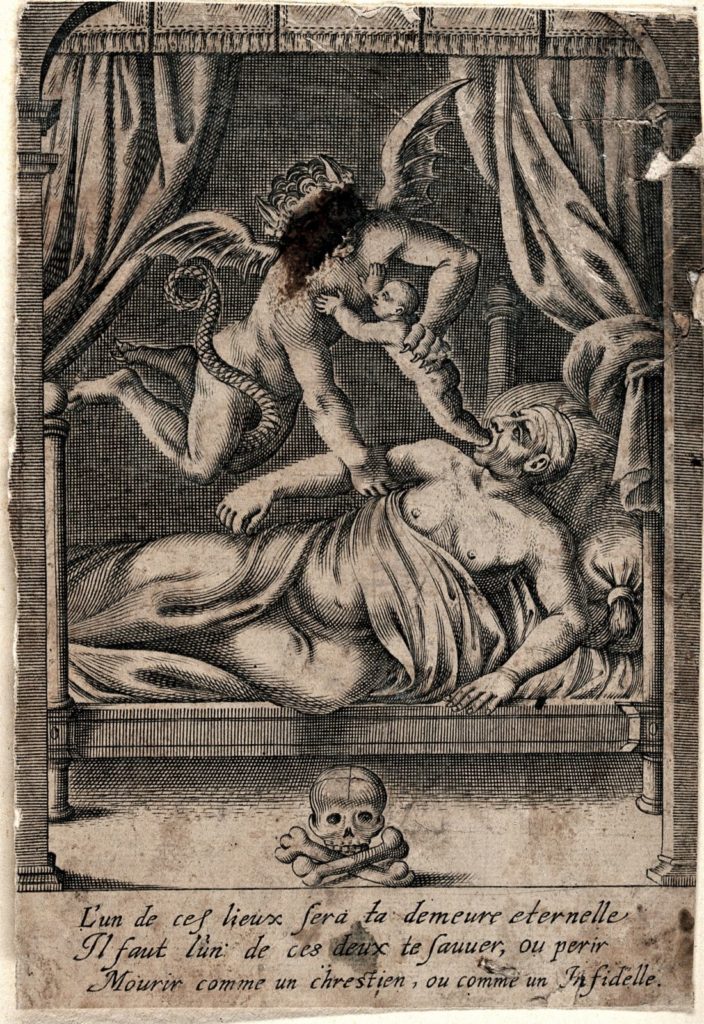

Artist Unidentified, A Deathbed: a man breathes his last, the devil flies down and grabs his soul (in the form of a baby) from his mouth, 17th century. Engraving, inscription: “L’un de ses lieux sera ta demeure eternelle, Il faut l’un de ces deux te sauver, ou perir, Mourir comme un chrestien, ou comme un infidelle” [loosely translated One of its places will be your eternal home, One of these two must save you, or perish, Die like a Christian, or like an infidel]. Wellcome Trust, London.

Artist Unidentified, A Deathbed: a man breathes his last, the devil flies down and grabs his soul (in the form of a baby) from his mouth, 17th century. Engraving, inscription: “L’un de ses lieux sera ta demeure eternelle, Il faut l’un de ces deux te sauver, ou perir, Mourir comme un chrestien, ou comme un infidelle” [loosely translated One of its places will be your eternal home, One of these two must save you, or perish, Die like a Christian, or like an infidel]. Wellcome Trust, London.

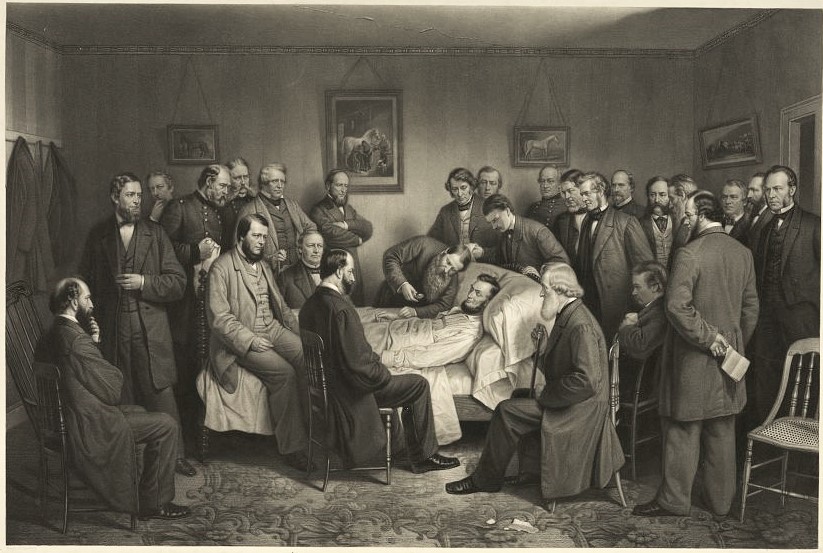

Alexander Hay Ritchie (1822-1895), Death of Lincoln, ca. 1874. Mezzotint. Graphic Arts Collection GA 2008.01243

Alexander Hay Ritchie (1822-1895), Death of Lincoln, ca. 1874. Mezzotint. Graphic Arts Collection GA 2008.01243

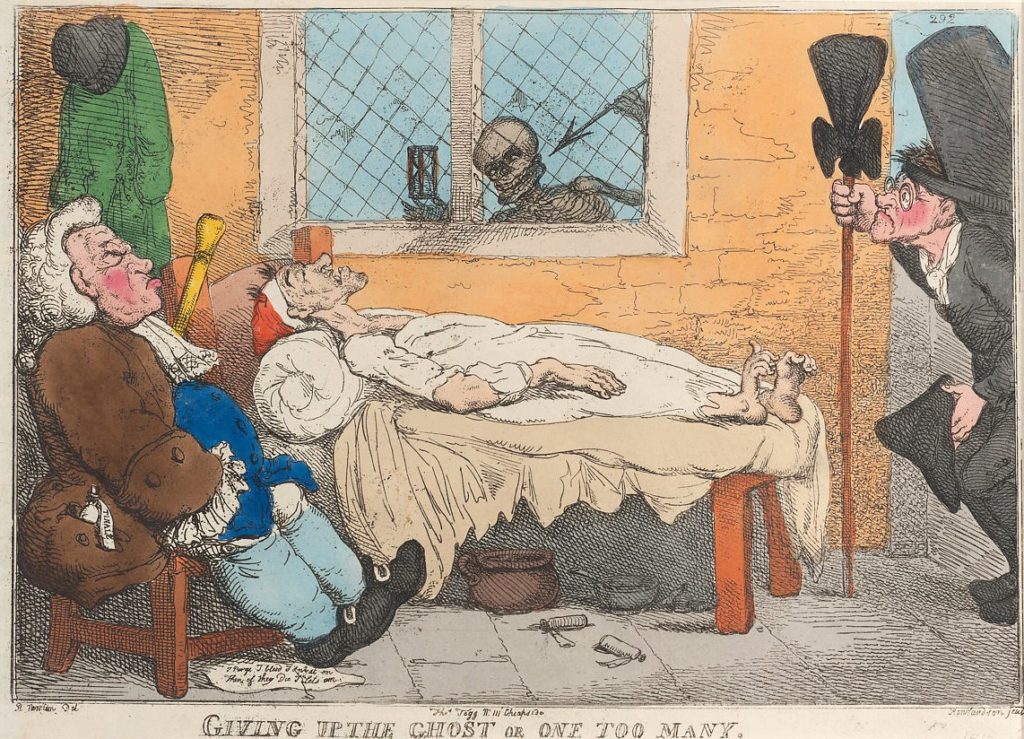

Thomas Rowlandson (1757-1827) after Richard Newton (1777-1798), Giving up the ghost or one too many, ca.1813. Hand colored etching. Graphic Arts Collection GA 2014.00260.

Thomas Rowlandson (1757-1827) after Richard Newton (1777-1798), Giving up the ghost or one too many, ca.1813. Hand colored etching. Graphic Arts Collection GA 2014.00260.

A dying man lies on a miserable bed. A fat doctor sits asleep at the bedside. Beside him are the words:

“I purge I bleed I sweat em

Then if they Die I Lets em”