When Anaïs Nin bought a printing press and set up shop in Greenwich Village, Jimmy Cooney made a number of trips into town to give her printing lessons and publishing advice. Who was he?

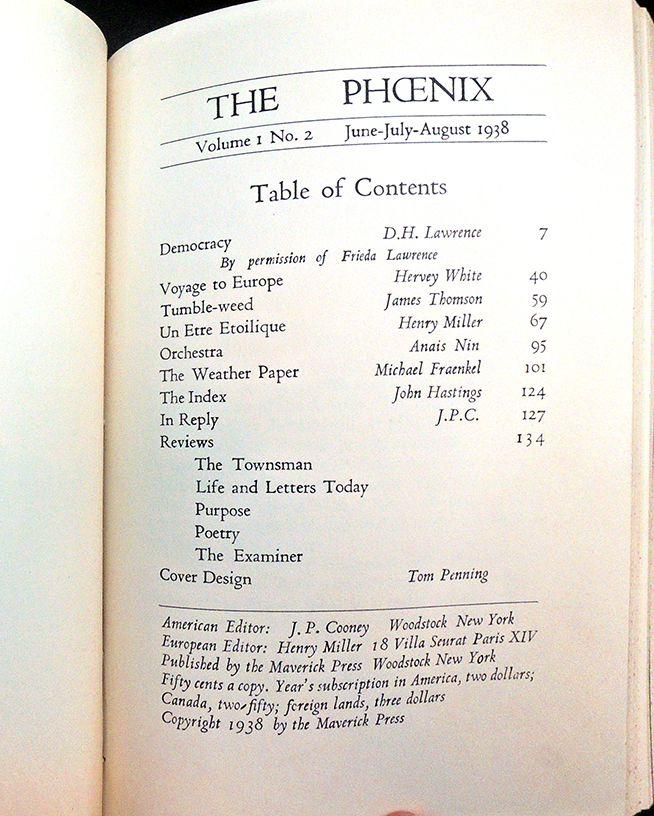

In the 1930s, Blanche and James Cooney moved “on the Maverick,” an artists’ colony outside Woodstock, NY, founded by Hervey White in 1905. They had no telephone or indoor plumbing but acquired a full stockpile of metal type and a small hand press. Notices were placed in The New York Times Sunday book review section and the Herald Tribune asking for manuscripts to be published in a new magazine. “We would print it ourselves; it would be the rallying point, through it we would spread the word of a community of separate dwellings and shared land and stock and tools; …We would publish writers whose unpopular or seditious views would have no chance in the commercial press.” It would be called The Phoenix, in honor of D.H. Lawrence.

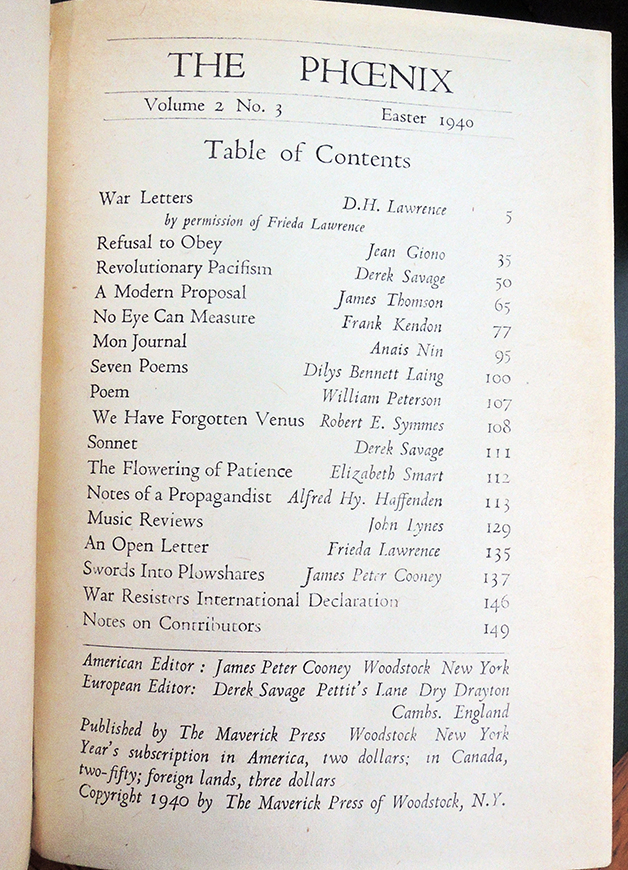

Henry Miller wrote from Paris that both he and his friend Anaïs Nin would send material, happy that someone welcomed their provocative stories. Each was published in The Phoenix several times before they were forced to leave Paris for New York City.

As soon as Anaïs was settled, she and her husband Hugh Guiler (Hugo) made a pilgrimage to meet the Cooneys and the press that was not afraid to publish her work. Anaïs’s famous diaries do not mention of this trip, probably because Hugo asked her not to write about him and she agreed. However, the visit is chronicled in Blanche Cooney’s autobiography:

“In 1940, on her return from Europe, Anaïs came to Woodstock with her husband Hugh Guiler to stay with us for a few days. She wanted to meet her first American publisher, we wanted to meet the fabled Etre Étoilique [Miller’s 1937 short story about Anaïs]. A great pleasure to look at, she moved like the dancer she was, a fluid supple line in a dress of purple wool. . . Hugo—Anaïs called him Hugo and he said we were also to call him Hugo—was the banker, an international banker. A tall lean Scotsman, gentle, handsome, he deferred to Anaïs, his adored one, his indulged one. No whim, no quirk, no passion, or bizarre appetite would he deny her, Yes to a houseboat on the Seine, Yes to the Miller connection, to a fling with a woman, an English poet, a Peruvian Indian, Yes….

Hugo, Anaïs said, will be studying engraving with Stanley Hayter at the New School. Hugo had a definite talent; he will do the covers and illustrations for her books, she said; they will find a printer and publish privately. “my text and Hugo’s decorations.” Anaïs smiled into Hugo’s eyes with intimate secret reference. The visit went well, no explosions, no denunciations . . . .”–Blanche Cooney, In My Own Sweet Time (Ohio: Swallow Press, 1993). Z473 .C755 1993

The Phoenix ([Haydenville, Mass.: Morning Star Press, 1938-1984.]). Vol. 1, no. 1 (Mar./May 1938)-v. 9, no. 3 & 4 (1984). AP2 .P464

Natashia Troubetskoia, Anaïs Nin, ca. 1932. Oil on canvas. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Natashia Troubetskoia, Anaïs Nin, ca. 1932. Oil on canvas. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Want to know more? Please join us at 2:00 p.m. on September 25, 2020 for the fifth in our series of webinars highlighting the Graphic Arts Collection at Princeton University. Register for free here: https://libcal.princeton.edu/event/6949414

The history of the Maverick: https://player.vimeo.com/video/11435652