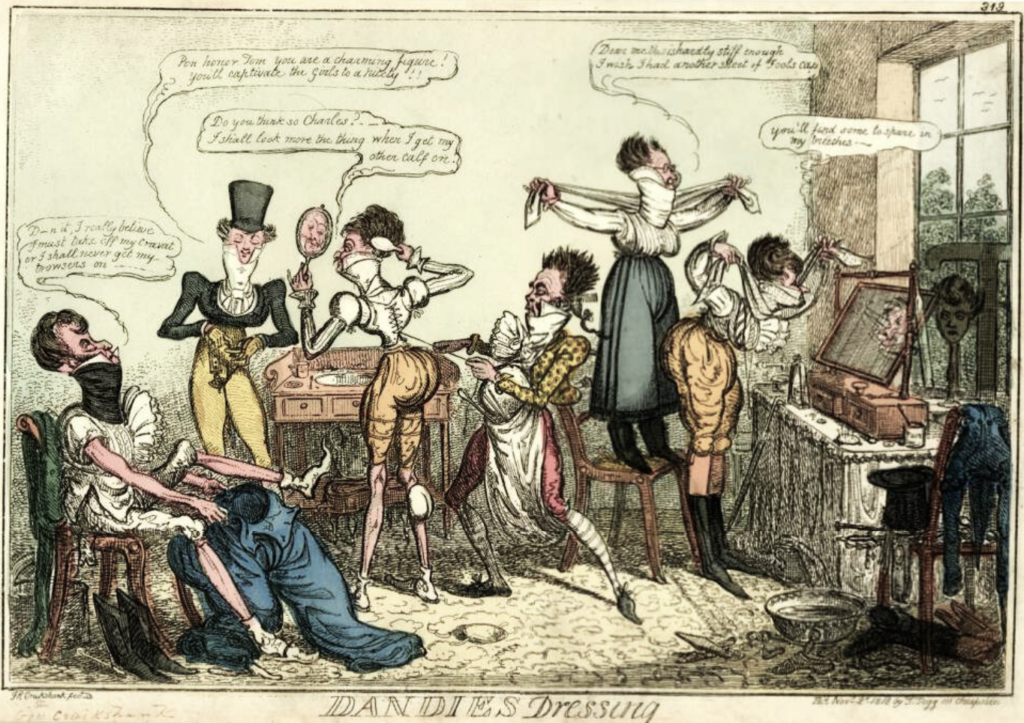

Isaac Robert Cruikshank (1789-1856), Dandies Dressing, November 2, 1818. Hand colored etching. From Dandies series published by Thomas Tegg. Graphic Arts Collection. I.R.Cruikshank prints

Isaac Robert Cruikshank (1789-1856), Dandies Dressing, November 2, 1818. Hand colored etching. From Dandies series published by Thomas Tegg. Graphic Arts Collection. I.R.Cruikshank prints

High white collars came into fashion for men in the 18th century, at a time when the shirt, collar, and cravat were all washed and bleached together, causing considerable time and trouble for wives and maids. The invention of the removable collar has been claimed, at least in the United States, by Hannah Montague of “Collar City” (Troy, NY). As early as 1827, Montague came up with the idea of cutting one collar off her husband’s shirt that could be laundered separately and then buttoned back onto various shirts. See also:

https://hoxsie.org/2012/02/06/how_the_collar_city_got_its_name/

Most histories agree the first patent for a disposable paper collar was granted to the New York inventor Walter Hunt (1796-1859) on July 25, 1854 (who was also responsible for an early sewing machine and the first safety pin). In Philadelphia, William E. Lockwood established his own collar company a few years later but it wasn’t until the US Civil War and a cotton shortage that the sale of paper collars exploded.

In 1863 Lockwood bought or otherwise acquired the patents held by Solomon Gray and Andrew Evans. He then gathered 19 paper collar manufacturers together to form The Union Paper Collar Company, presuming they would control the market. The company placed warnings in local newspapers around the country telling people not to buy from any firm other than Union Paper Collar Co. Lawsuits were threatened.

For Christmas 1865, the New York Times ran a promotional story of a shopping trip a reporter took with an out-of-towner called O’Leum. Various shops and their merchandise were described, including S.W.H. Ward’s paper collars: “O’Leum has heard of WARD’s perfect fitting shirts and WARD’s handsome paper collars and cuffs for ladies and gentlemen. He therefore insists upon a visit to Mr. S.W.H. WARD, at No. 387 Broadway. The only wonder is that O’Leum, who appears to be an incorrigible traveler, and has almost wearied our reporter, does not also propose a trip to WARD’s other store, at Nos. 323 Montgomery-street, San Francisco. WARD sells O’Leum a gross of India-rubber enameled collars and cuffs and we are off … “–NYT December 21, 1865.

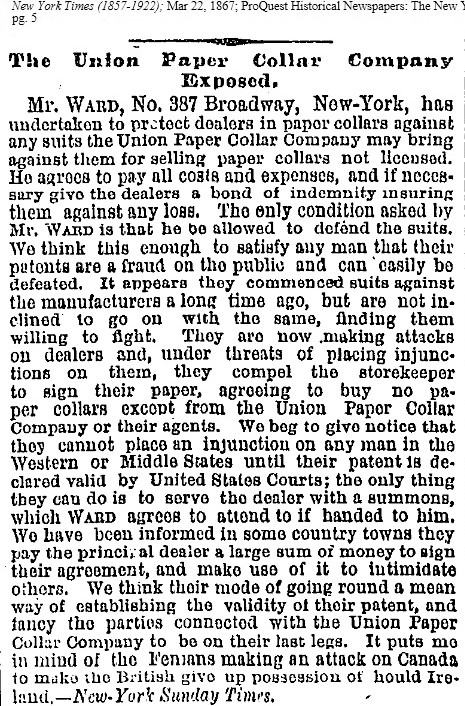

Ward was among the companies that did not want to join the Union Paper Collar Co monopoly and so, in 1866 they formed their own collective known as the United States Paper Collar Manufacturers’ Association. Ward published his own advertisement [at the top], offering $20,000 if Lockwood or any member of the Union Paper Collar Company went forward with a lawsuit.

Only years later did several small suits move forward, one as far as the United States Supreme Court: the Union Paper Collar Co VS Van Dusen in October 1, 1874, which Lockwood lost.

The transcript is a wonderful document, with full descriptions of how the paper for collars was made, how it was cut and fashioned, as well as the machines used for these processes. The Court said new machines could be patented but not the original concept of a removable paper collar, which had already been created. Here’s a short section:

“After the “stock” — best rags or what else — is sorted and cut, it is generally cleaned by boiling, and finally put, with the requisite quantity of water, into the “beating engine,” where it is beaten or ground into pulp. The beating engine is simply a vat divided into two compartments by a longitudinal partition, which, however, leaves an opening at either end. In one compartment a cylinder revolves, called the “roll,” its longitudinal axis being at right angles to the length of the vat. In this cylinder, and parallel with its axis, are inserted a number of blades or knives which project from its circumference. Directly beneath the roll, upon the bottom of the vat, is a horizontal plate, called the bed-plate, which consists of several bars or knives, similar and parallel to those of the roll, bolted together. The roll is so arranged that it can be raised or lowered, and also the speed of its revolutions regulated at pleasure. The vat being filled with rags and water, in due proportion, the mass is carried beneath the roll, and between that and the bed-plate, and passing round through the other compartment of the vat, again passes between the bed-plate and roll, and so continues to revolve until the whole is beaten into pulp of the requisite fineness and character for the paper for which it is intended. When the beating first begins, the roll is left at some distance from the bed-plate, and is gradually lowered as the rags become more disintegrated and ground up. The management of the beating engine is left to the skill and judgment of the foreman in charge. The knives may be sharp or dull, the roll may be closely pressed upon the bed-plate or slightly elevated, the bars and knives may have the angles which they make with each other altered, so that they either cut off sharply, like the blades of scissors, or tear the rags more slowly as they pass between them. The duration of the beating also varies according to the nature of the pulp, the length of fiber required, the condition of the knives &c.; and the speed of the revolutions given to the roll is varied in like manner.

One of the many companies saved by this ruling was the Reversible Collar Company in Cambridge, Massachusetts, whose factory building is still standing at 25–27 Mt. Auburn & 10–14 Arrow Streets, although no paper collars are being produced.