In 1799, Michel Etienne Descourtilz, a French naturalist and surgeon, arrived at Saint Domingue on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola and remained there nearly four years, during which time the indigenous people revolted. Today the island hosts the Dominican Republic and Haiti. Although Descourtilz collected samples, documented language and music, and made sketches, many of his belongings were destroyed during the revolution. Returning to Paris, it took him five more years to complete his narrative, first published in 1809.

“The first-person accounts by whites taken prisoner during the interracial violence in Saint-Domingue during the revolutionary era … were written primarily to refute opponents of slavery in revolutionary France. Precisely because their authors had personally confronted a situation in which black slaves had at least provisionally defeated the white world-the only such situation in the Atlantic world up to that time-these narratives are of extraordinary interest for the development of modern discourses about race and identity.

The Saint-Domingue insurrection, which began in 1791 and culminated in the creation of the independent black republic of Haiti in 1804, has haunted thinking about race throughout the Western world ever since. …The insurrection demonstrated that people of color could not only be active agents in the making of history, but that they could overthrow white rule and seize control of the crown jewel of one of the great European empires, the most valuable piece of colonial real estate in the world at the time. Toussaint Louverture, the black leader who emerged to lead this movement, represented slaveholders’ worst nightmare, and his saga became an inspiration for movements for freedom among people of color on both sides of the Atlantic.

Compared to the number of narratives about North American whites captured by Native Americans or white Europeans enslaved in the “Barbary states” of North Africa, the corpus of first-person testimonies from the Saint-Domingue uprising is small. Only two fairly lengthy accounts published at the time are known: the colonist Gros’s Historick Recital, of the Different Occurrences in the Camps of Grand-Reviere…, and the naturalist Michel Etienne Descourtilz’s Voyages d’un naturaliste, which recounts the author’s experiences from 1799 to 1803, during Toussaint’s reign and in the war which resulted in the destruction of the last vestiges of white rule in Haiti.” —Jeremy D. Popkin, “Facing Racial Revolution: Captivity Narratives and Identity in the Saint-Domingue Insurrection,” Eighteenth-Century Studies , Summer, 2003, Vol. 36, No. 4 (Summer, 2003) URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30053605

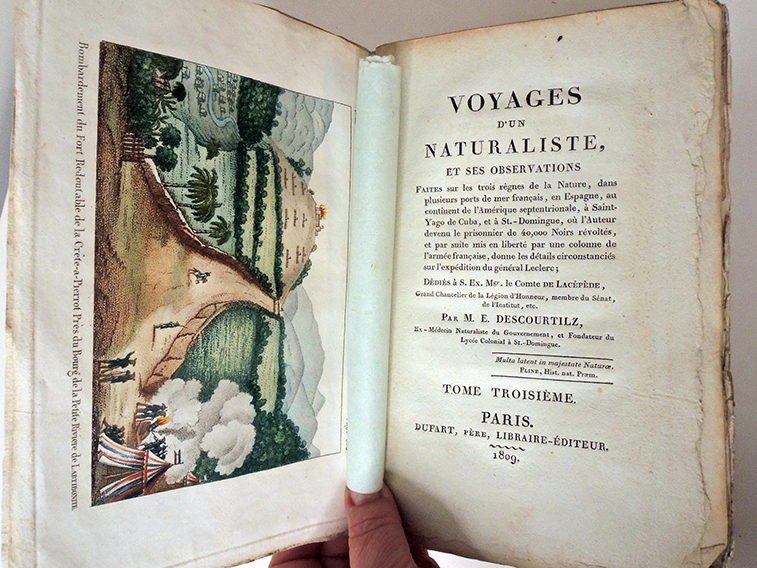

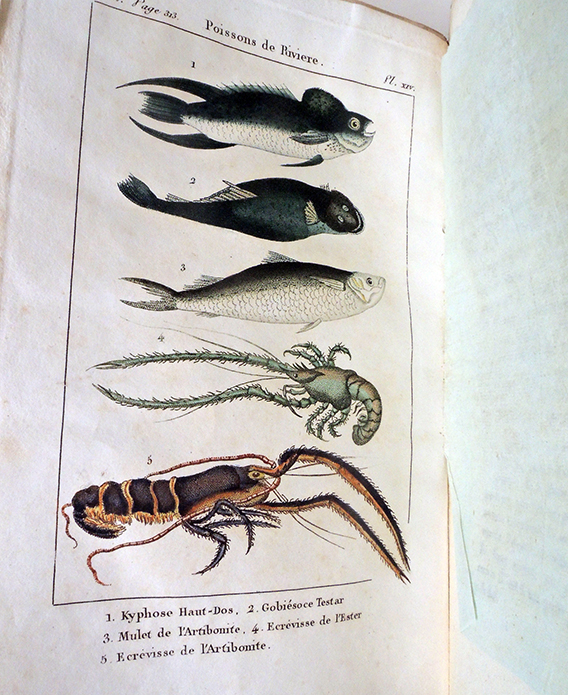

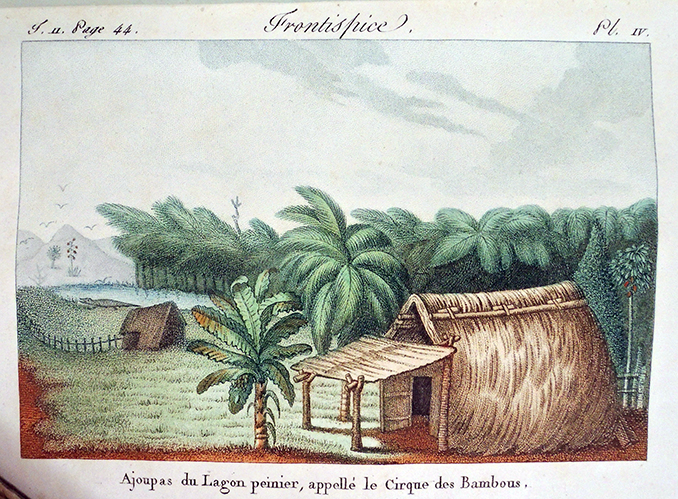

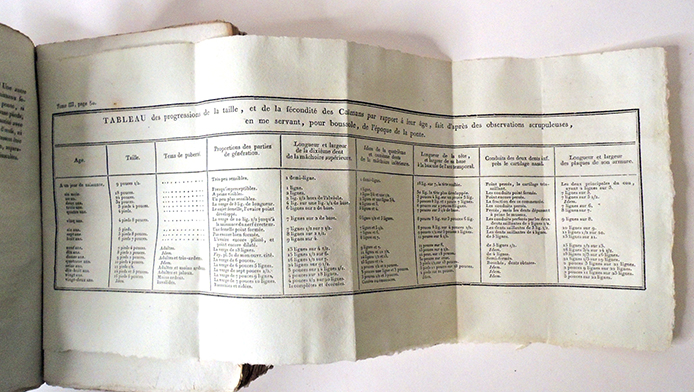

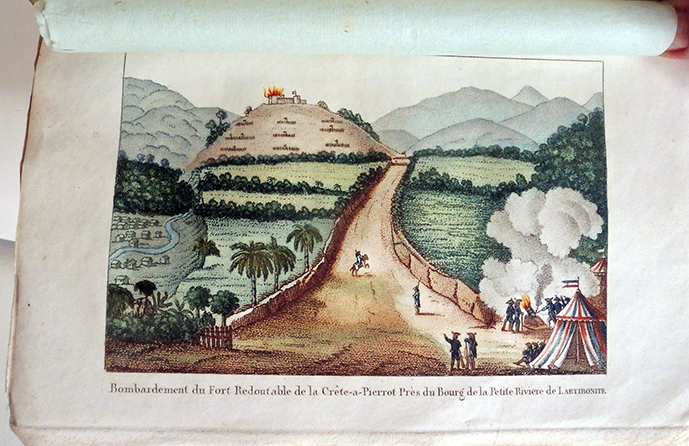

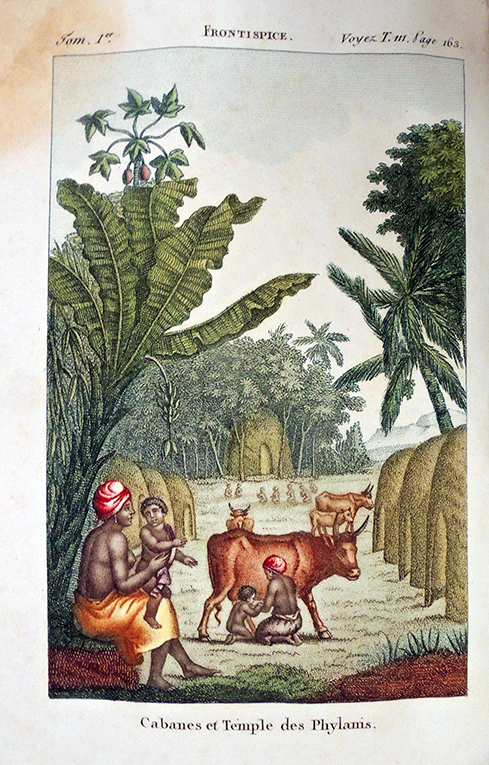

Michel Etienne Descourtilz (1775-1835), Voyages d’un naturaliste, et ses observations : faites sur les trois règnes de la nature, dans plusieurs ports de mer français, en Espagne, au continent de l’Amérique Septentrionale, à Saint-Yago de Cuba, et à St.-Domingue, où l’auteur devenu le prisonnier de 40,000 Noirs révoltés, et par suite mis en liberté par une colonne de l’armée française, donne des détails circonstanciés sur l’expédition du général Leclerc [Travels of a naturalist, and his observations: made on the three kingdoms of nature, in several French seaports, in Spain, in the continent of North America, in Saint-Yago de Cuba, and in Santo Domingo, where the author who became the prisoner of 40,000 revolting indigenous people, and consequently released by a column of the French army, gives detailed details of the expedition of General Leclerc] (Paris: Dufart père, 1809). Complete with 45 full-page colored stipple engravings (3 frontispieces); a conversation in Creole; and two local songs with musical scores. Graphic Arts Collection GAX2021- in process

Michel Etienne Descourtilz (1775-1835), Voyages d’un naturaliste, et ses observations : faites sur les trois règnes de la nature, dans plusieurs ports de mer français, en Espagne, au continent de l’Amérique Septentrionale, à Saint-Yago de Cuba, et à St.-Domingue, où l’auteur devenu le prisonnier de 40,000 Noirs révoltés, et par suite mis en liberté par une colonne de l’armée française, donne des détails circonstanciés sur l’expédition du général Leclerc [Travels of a naturalist, and his observations: made on the three kingdoms of nature, in several French seaports, in Spain, in the continent of North America, in Saint-Yago de Cuba, and in Santo Domingo, where the author who became the prisoner of 40,000 revolting indigenous people, and consequently released by a column of the French army, gives detailed details of the expedition of General Leclerc] (Paris: Dufart père, 1809). Complete with 45 full-page colored stipple engravings (3 frontispieces); a conversation in Creole; and two local songs with musical scores. Graphic Arts Collection GAX2021- in process