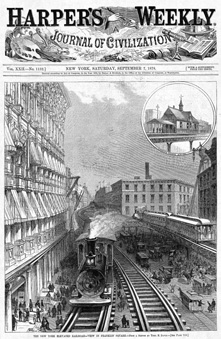

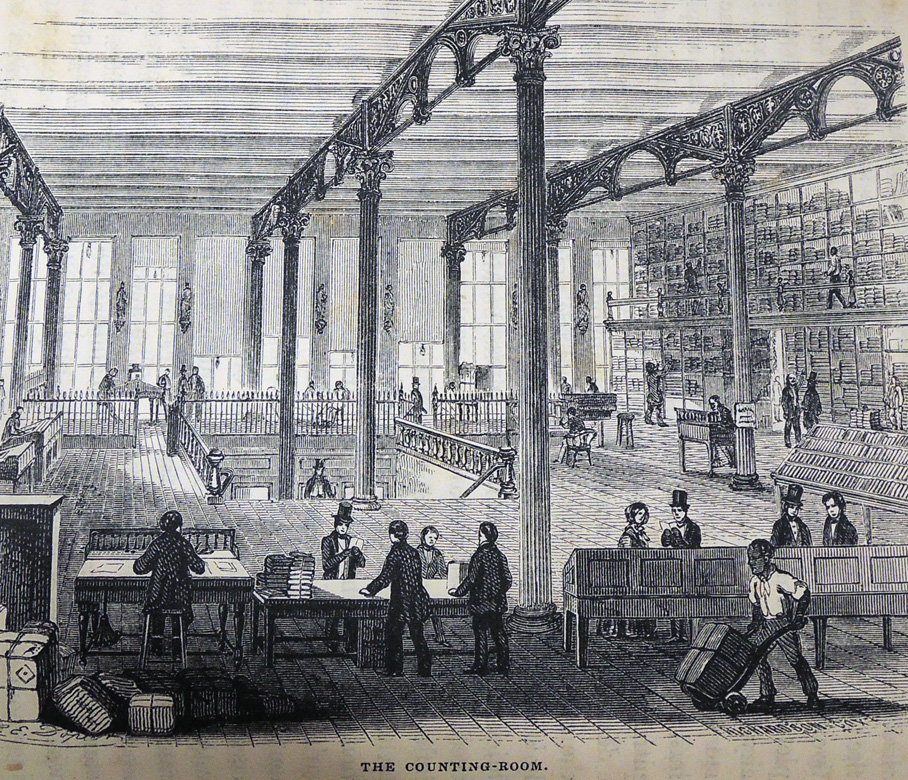

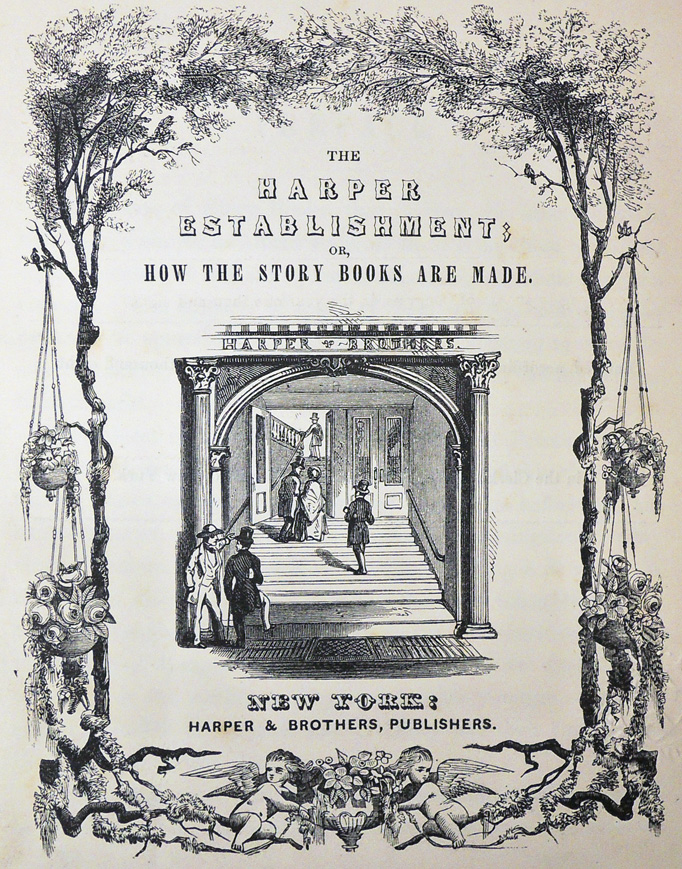

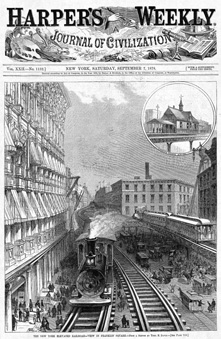

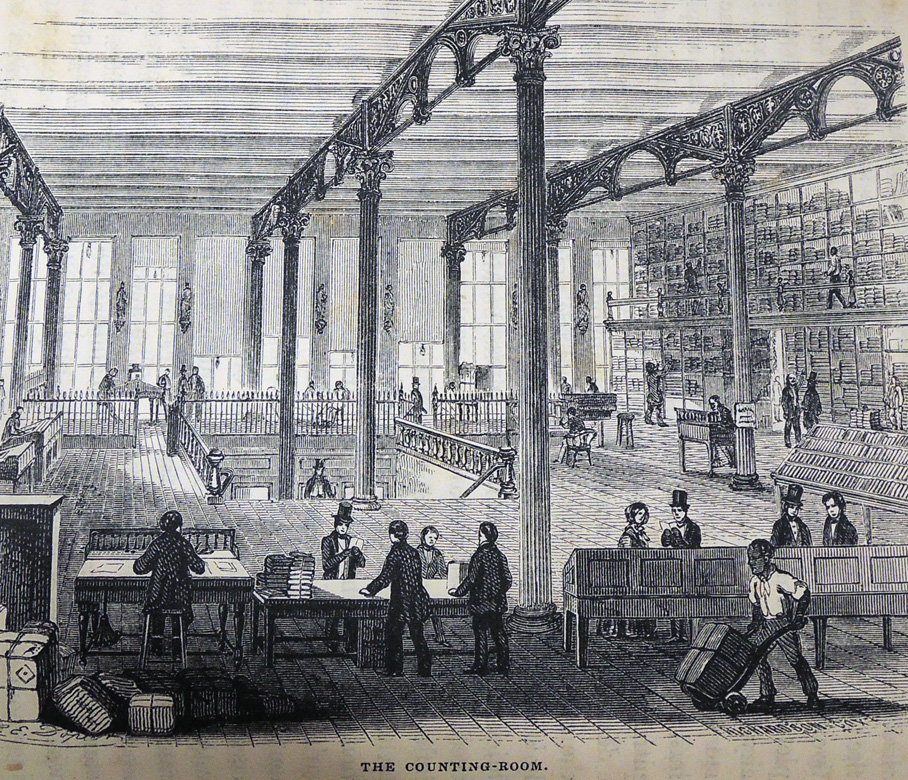

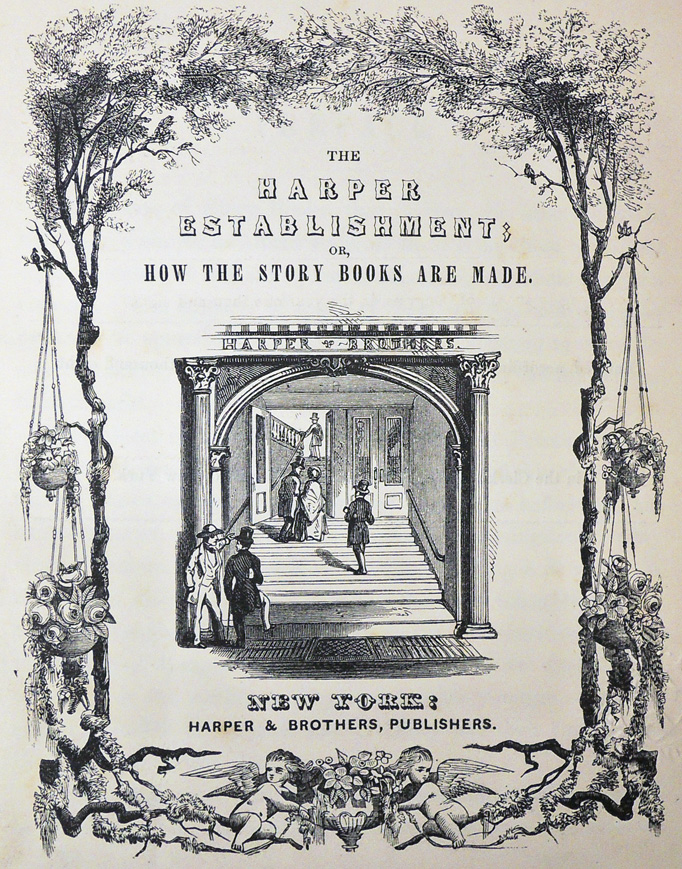

“When Harper & Brothers occupied its new publishing complex at Franklin Square in the summer of 1855,” writes Carol Gayle, “it was a model plant equipped with the latest types of rapid printing presses and using modern methods in every department. But in 1878 the Third Avenue elevated railroad was built. Its tracks ran along Pearl Street about 12 feet (4m) from the big windows of the editorial and sales departments.”

“When Harper & Brothers occupied its new publishing complex at Franklin Square in the summer of 1855,” writes Carol Gayle, “it was a model plant equipped with the latest types of rapid printing presses and using modern methods in every department. But in 1878 the Third Avenue elevated railroad was built. Its tracks ran along Pearl Street about 12 feet (4m) from the big windows of the editorial and sales departments.”

“The clatter and smoke from the trains distracted editors and visitors and disrupted meetings. A decade and a half later, what with economic upheavals and banking crises, and all four founding brothers dead, Harper & Brothers went into receivership. The firm’s days in the historic iron building at Franklin Square were numbered, although not until 1922 did the company’s leadership contract for a new brick building at 49 East 33rd street.” Margot Gayle and Carol Gayle, Cast-iron Architecture in America: The Significance of James Bogardus (1998). UES TH140.B64 G38 1998

Harper & Brothers announced that they would be moving from their Franklin Square building in the spring of 1922 and the November 25, 1922, issue of Publishers Weekly confirmed that “a lease has now been closed thru Douglas Gibbon & Co. for the building on the north side of Thirty-Third Street, directly adjoining the Vanderbilt Hotel on the west.”

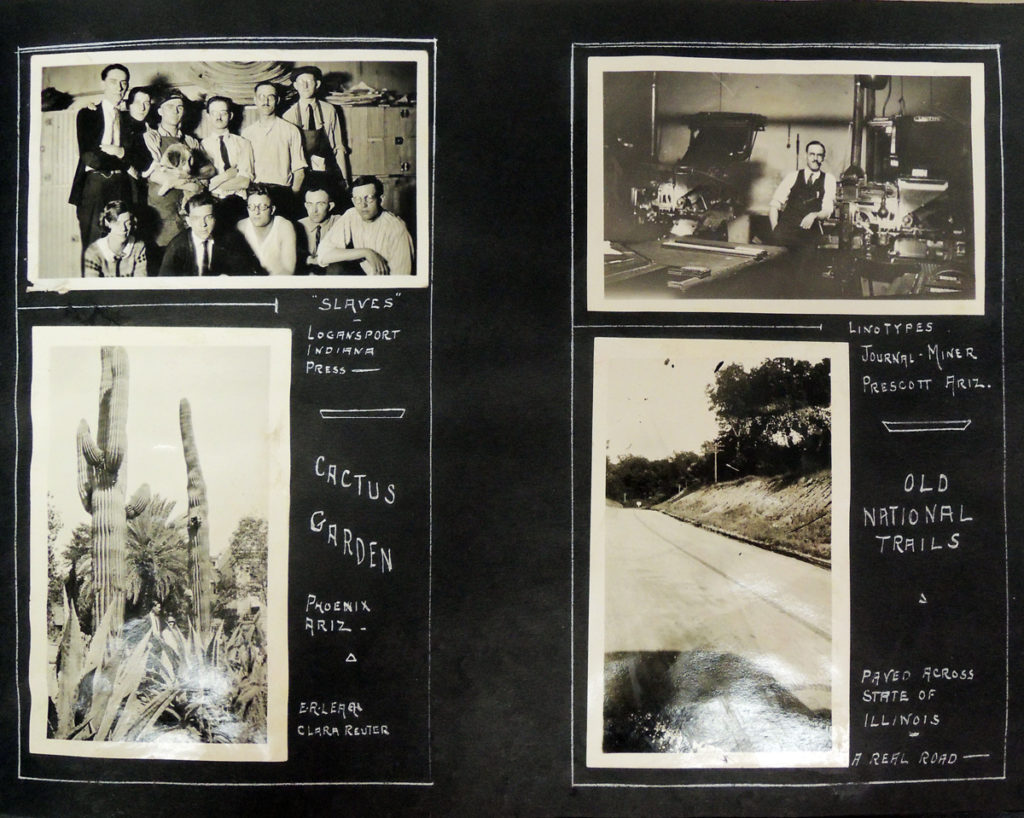

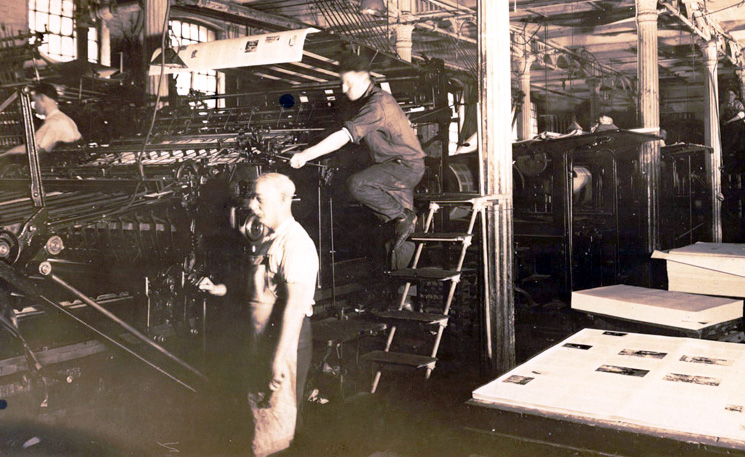

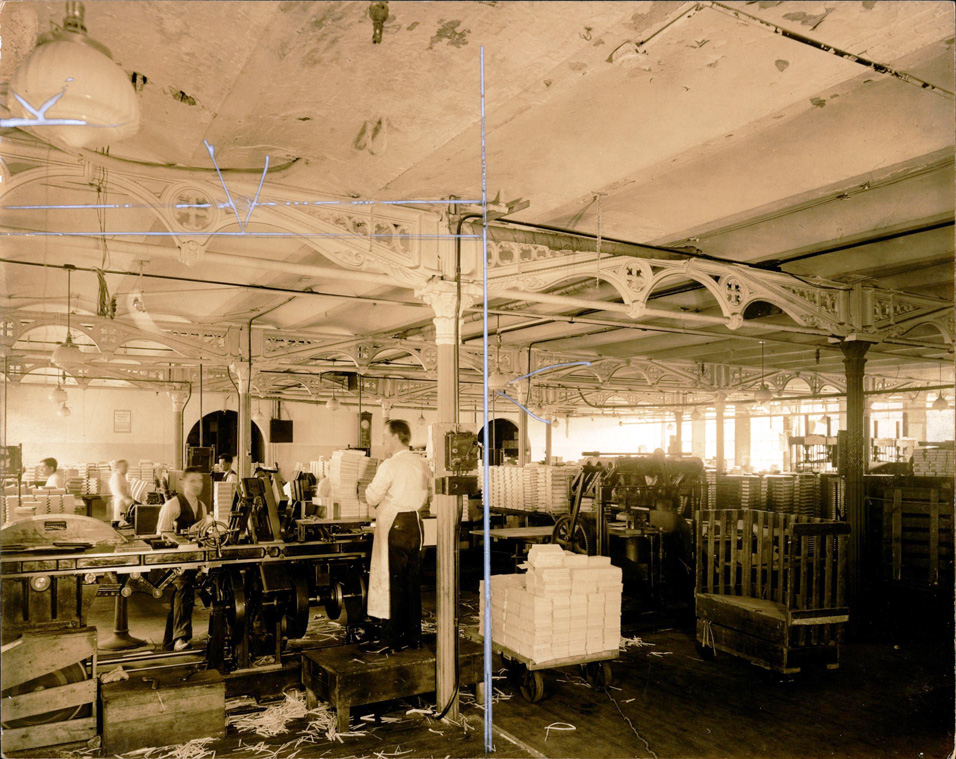

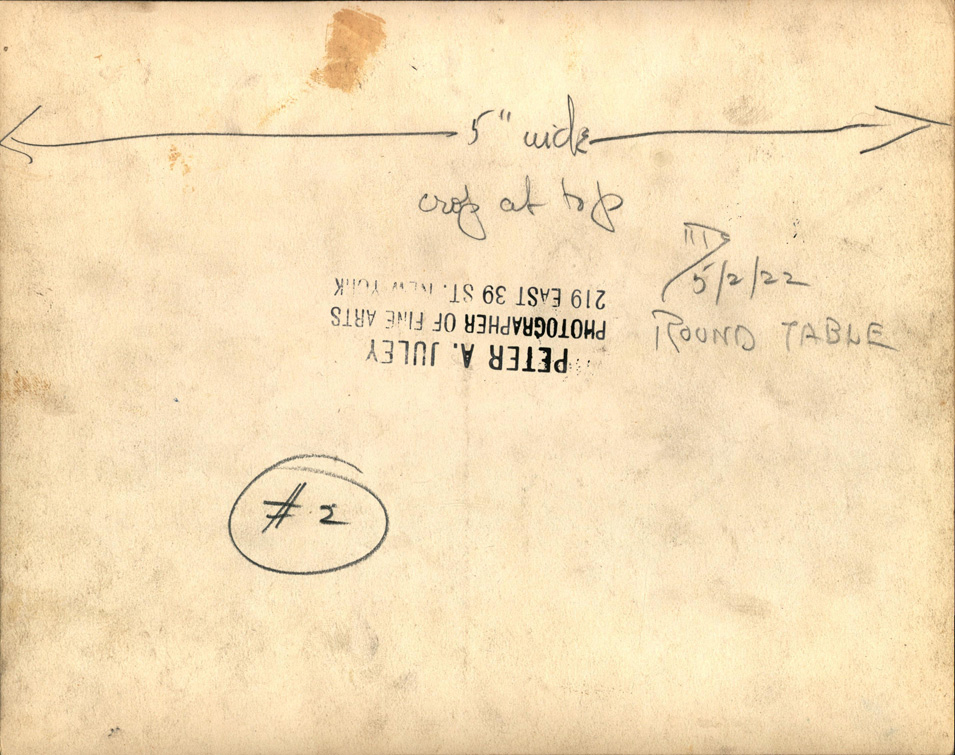

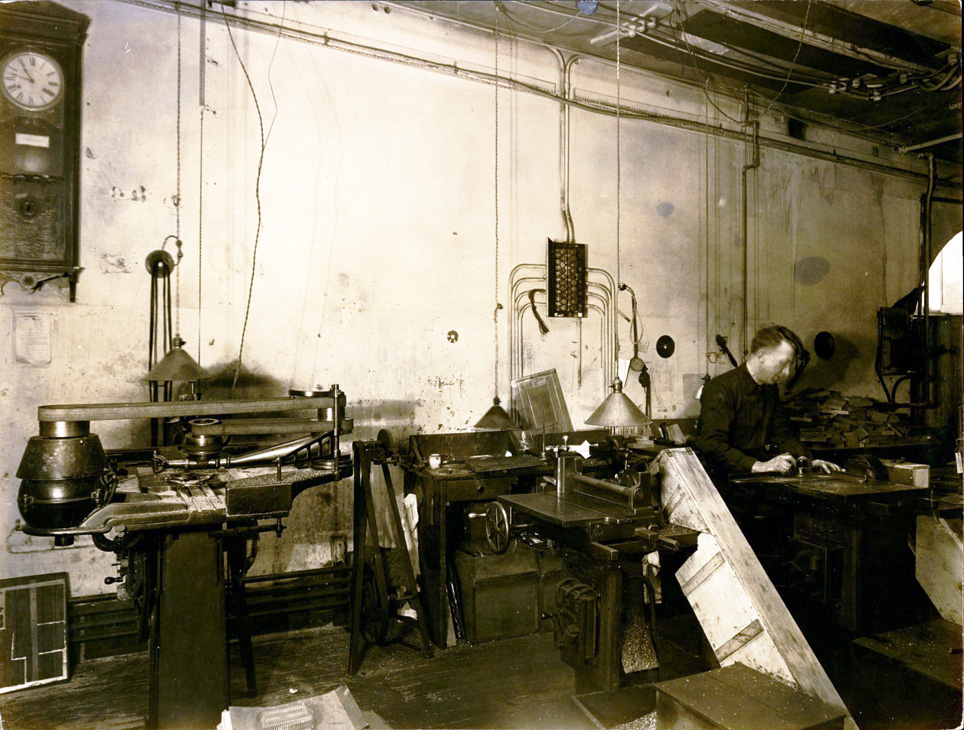

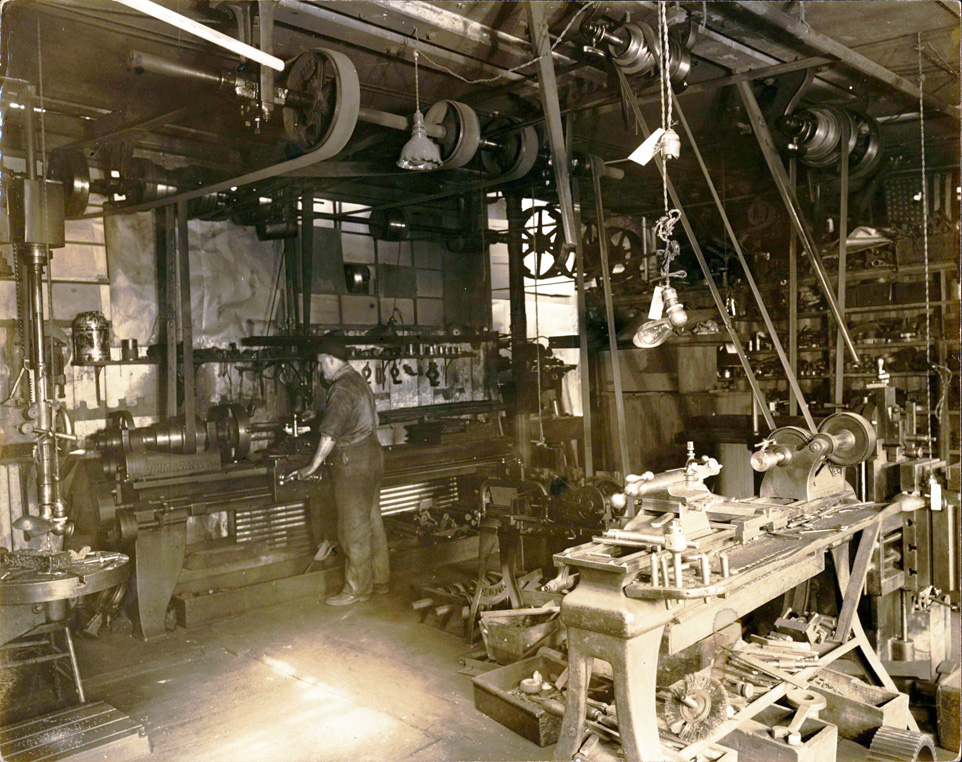

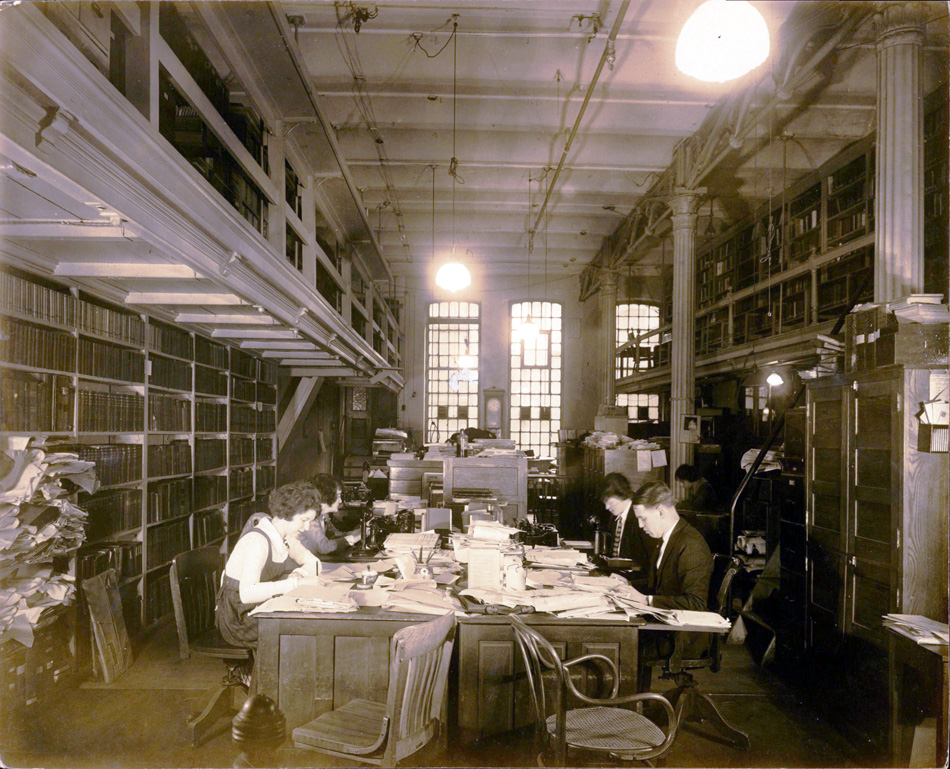

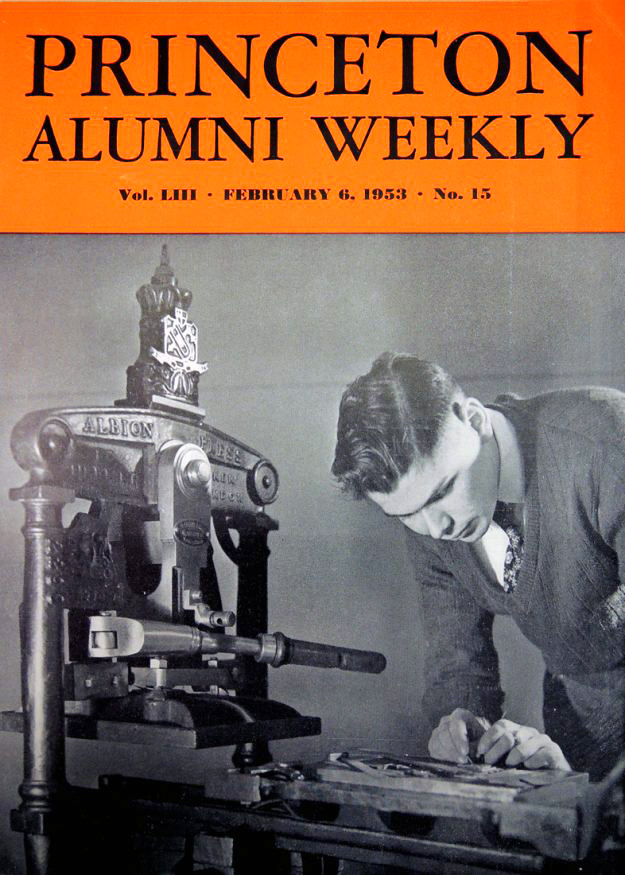

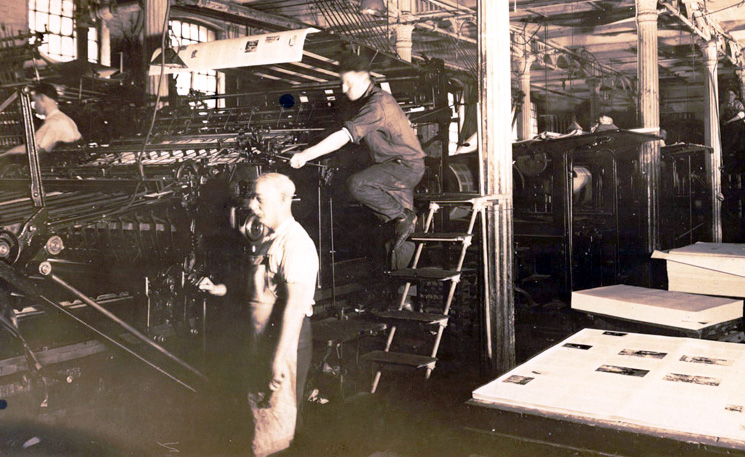

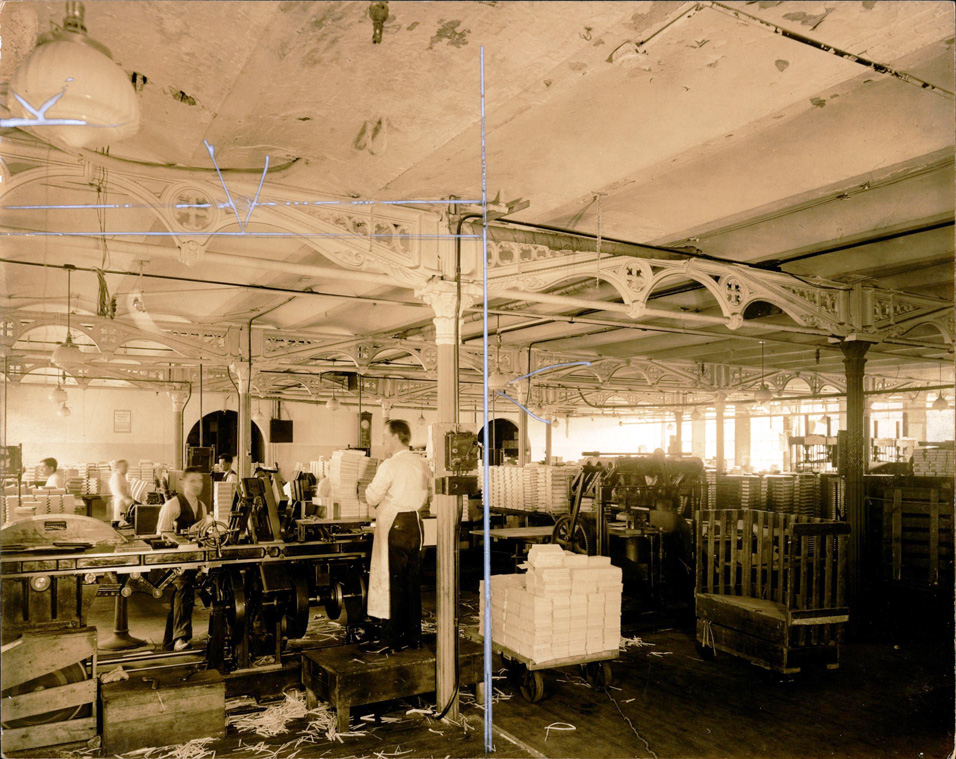

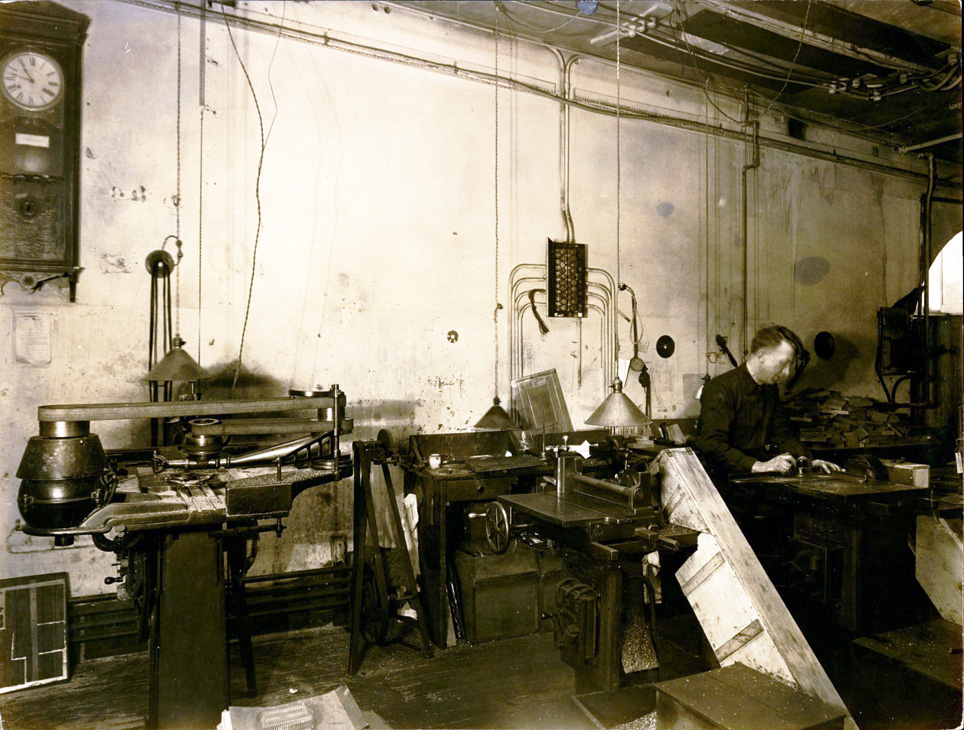

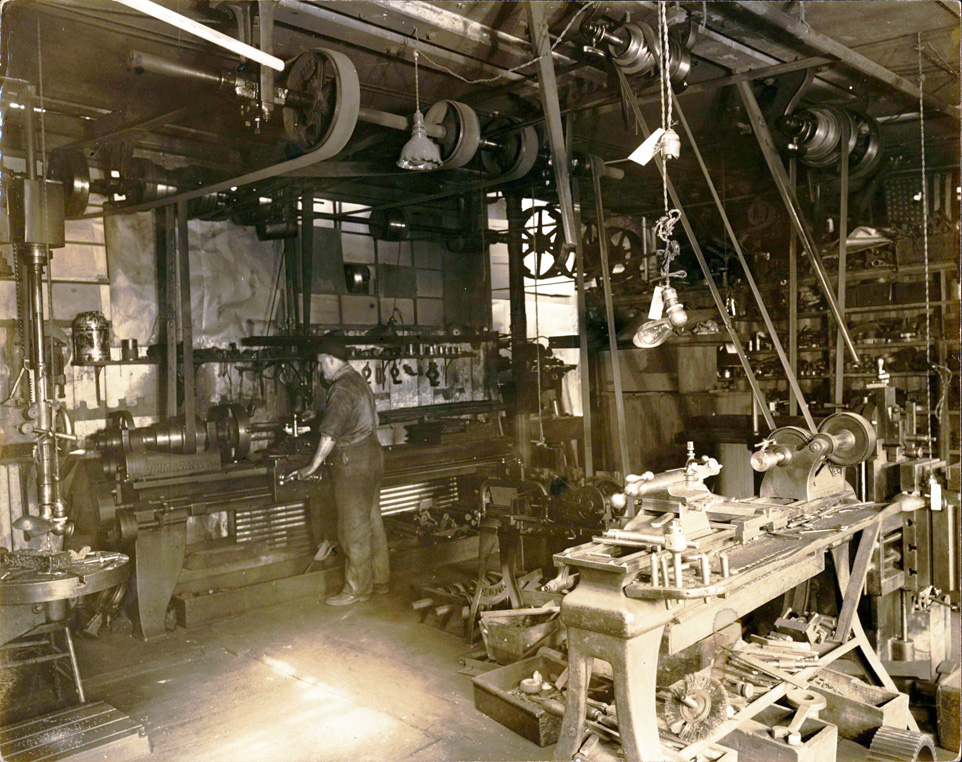

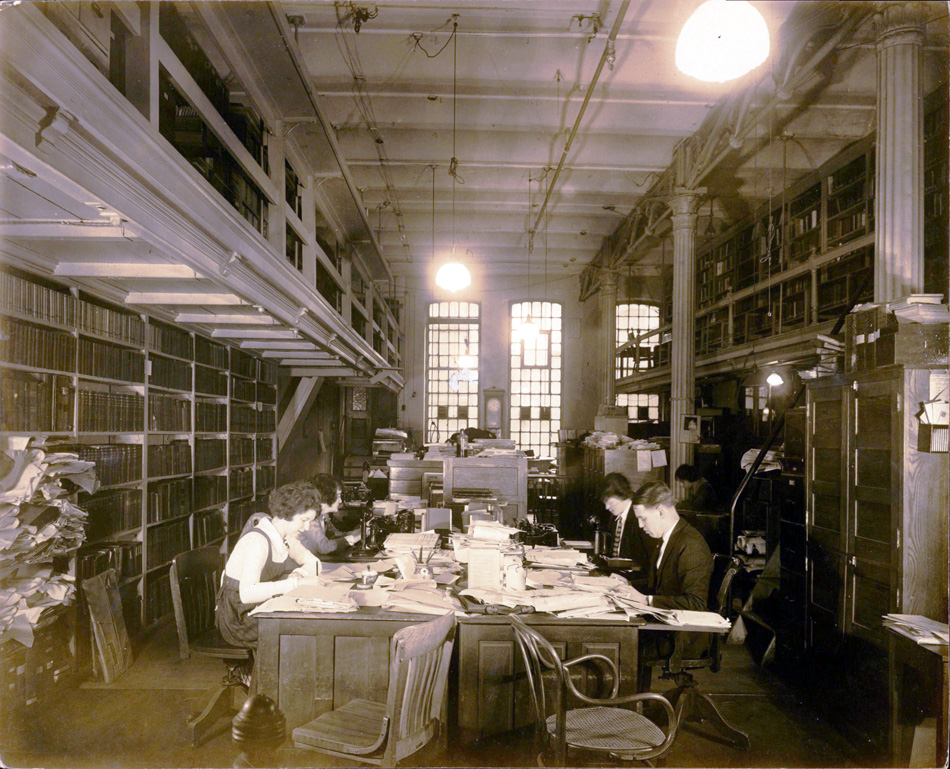

To document the firm’s landmark building and operations, Harper’s former staff photographer Peter A. Juley (1862-1937) was called back into duty. The Graphic Arts Collection recently acquired 22 photographs from that shoot capturing many aspects of book production in the old building. When the company moved, the presses were closed and all printing was out-sourced to a plant in New Jersey.

The set of photographs includes staff performing various tasks such as collating, typesetting, inking plates, printing, typing, writing, and photographing. Also pictured are exterior views of the building including the loading docks, street view, and entrance.

Peter Juley opened a small portrait studio in Cold Spring, New York, around 1896 and within five years joined Harper’s Weekly as a staff news photographer. Demand for his talented work increased rapidly, prompting Juley to relocate to Manhattan where he continued to work with Harper & Brothers until 1909.

Juley is best known for his portraits of American artists, now archived in the Archive of American Art. With his son Paul, the studio also served as official photographers for the Salmagundi Club, National Academy of Design, the New York Public Library, and the Society of American Artists.

See: American Artists in Photographic Portraits: from the Peter A. Juley & Son Collection, National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, compiled and written by Joan Stahl (New York: National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution in association with Dover Publications, 1995). Marquand Library (SAPH): Photography TR681.A7 N34 1995

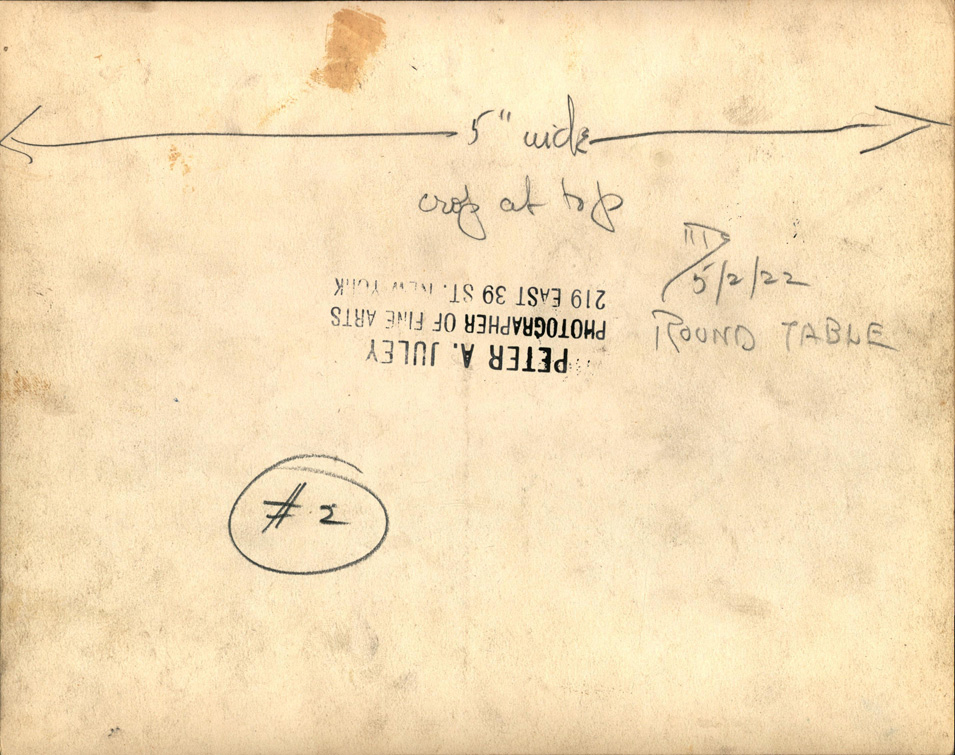

No published source has been found for these photographs. Several of them are marked for cropping and on the back, noted “5/2/22 Round Table,” the name of a children’s magazine that was no longer being published in 1922. It has been suggested that there might have been hopes of reviving the title, which never happened.

No published source has been found for these photographs. Several of them are marked for cropping and on the back, noted “5/2/22 Round Table,” the name of a children’s magazine that was no longer being published in 1922. It has been suggested that there might have been hopes of reviving the title, which never happened.

Peter A. Juley, “Pictures of Old Plant,” April 1922. 22 gelatin silver prints. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2017- in process.

Peter A. Juley, “Pictures of Old Plant,” April 1922. 22 gelatin silver prints. Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2017- in process.

We digitized the photographs on a flatbed scanner and some of the scans seen here are much darker than the original photograph. The contrast in both is high, given the strong light from the large windows.

We digitized the photographs on a flatbed scanner and some of the scans seen here are much darker than the original photograph. The contrast in both is high, given the strong light from the large windows.

Note the enlarging camera and ancient photographic equipment. Can anyone tell us why they kept an ice trunk in the studio?

Note the enlarging camera and ancient photographic equipment. Can anyone tell us why they kept an ice trunk in the studio?

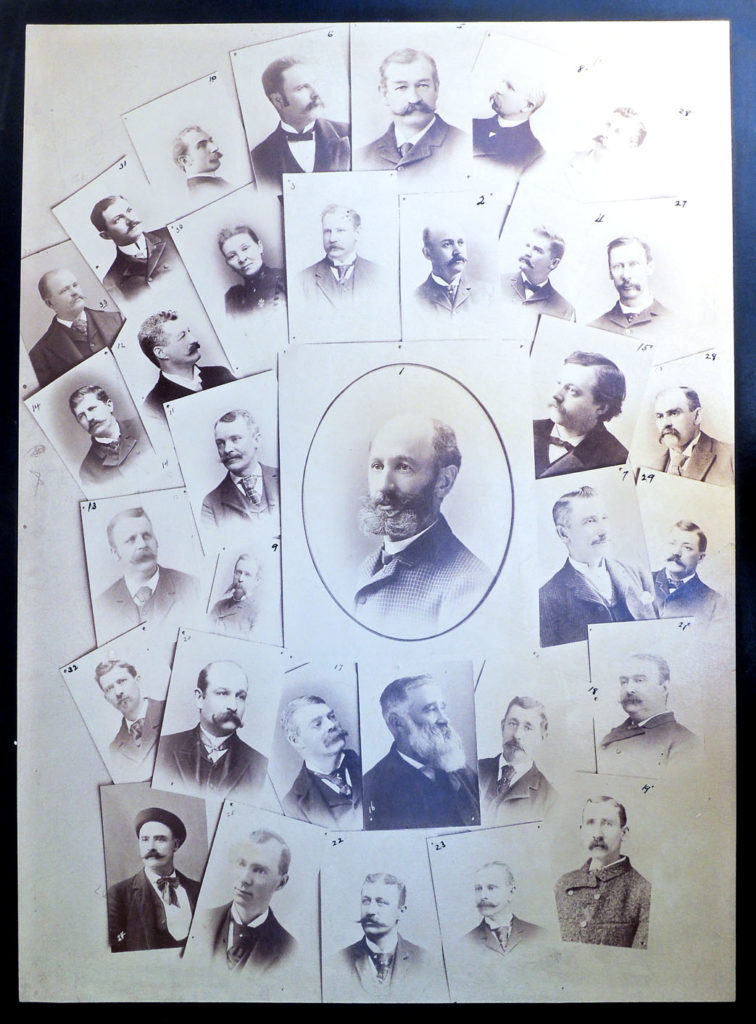

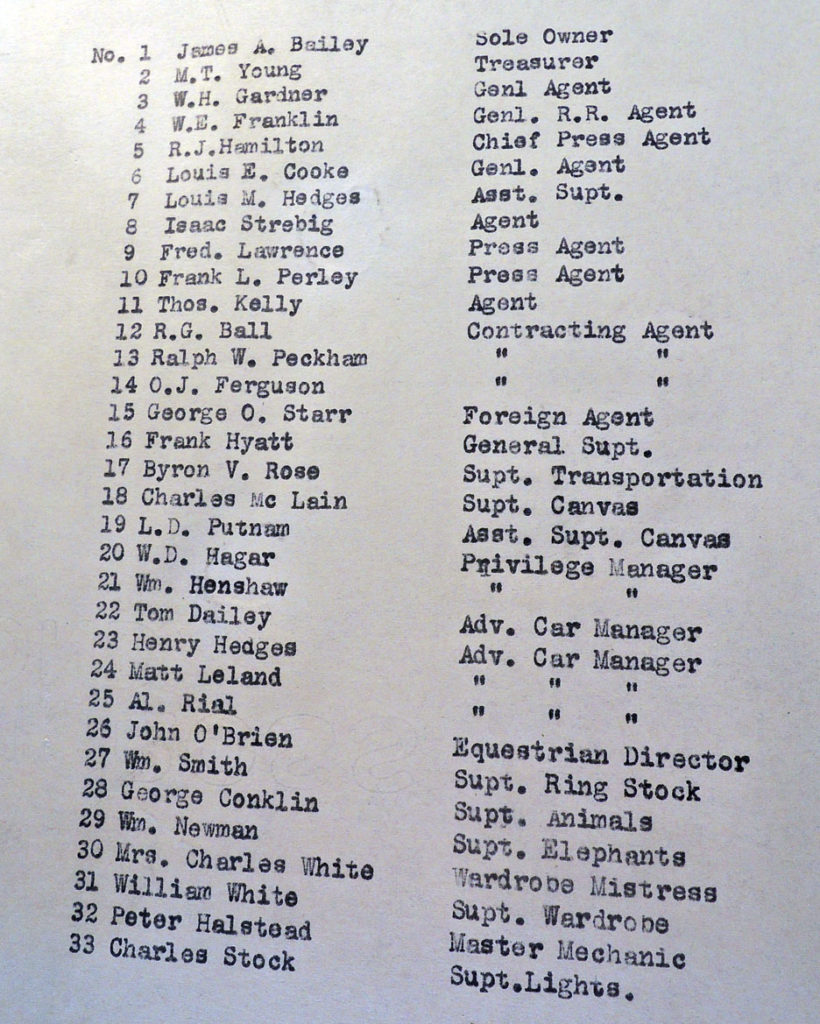

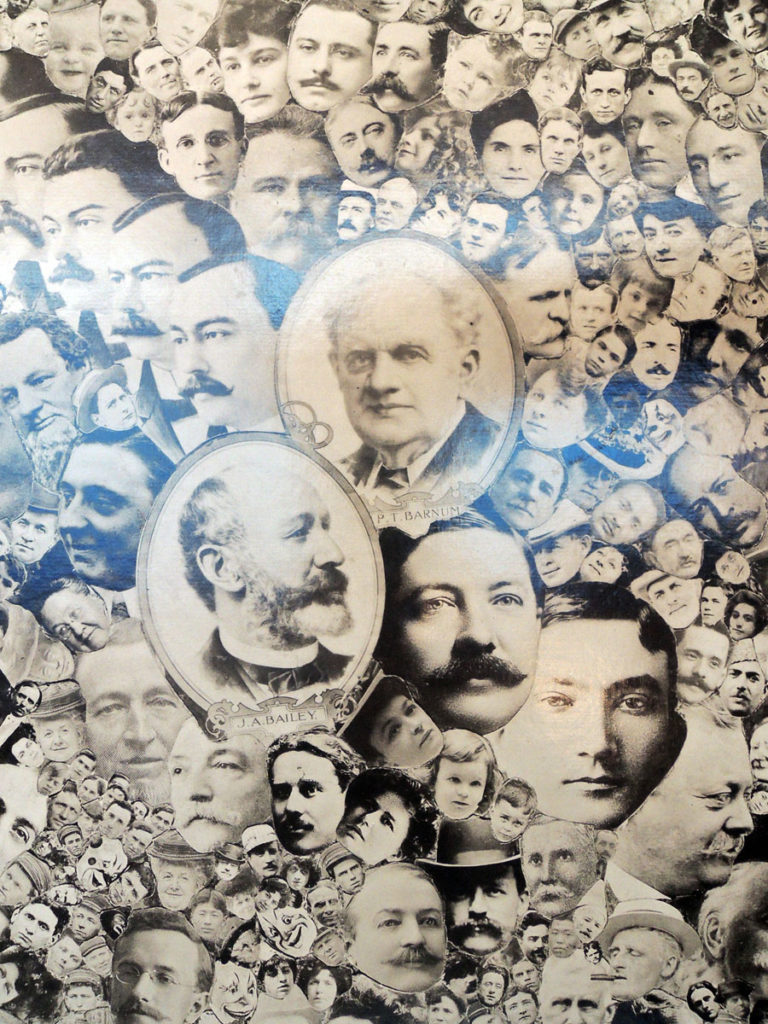

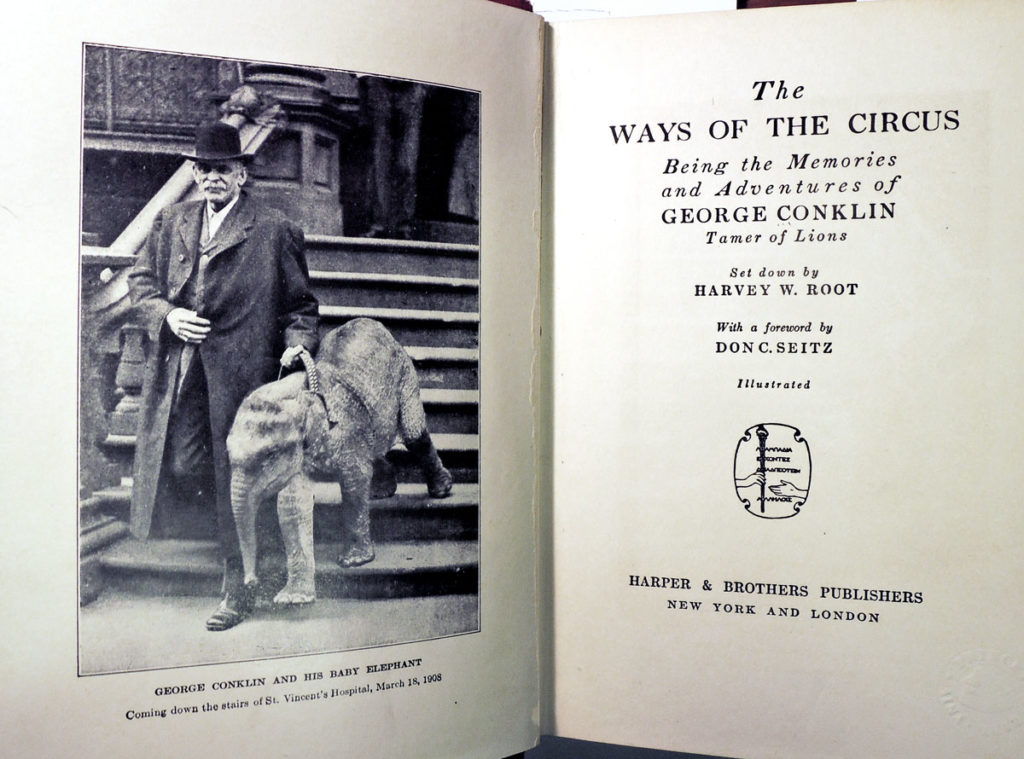

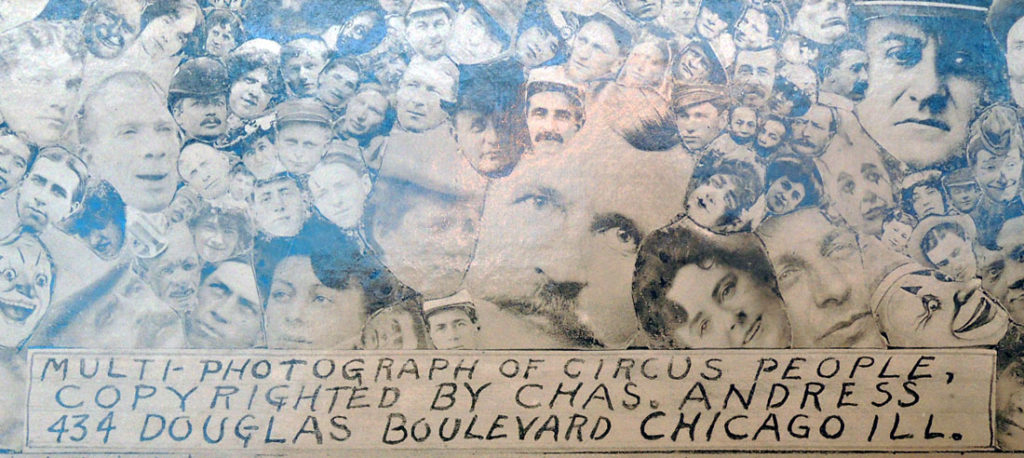

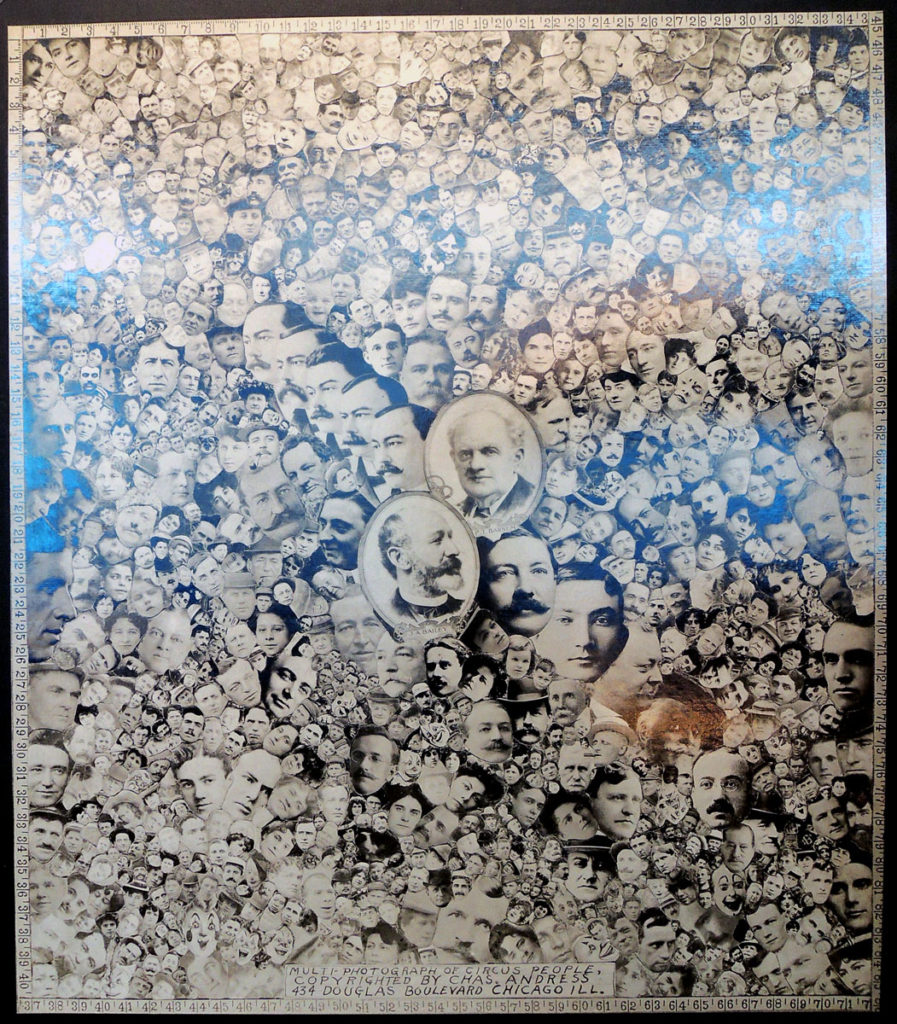

The Graphic Arts Collection holds two composite photographs of circus people. One is organized and indexed. The second, well, the second isn’t.

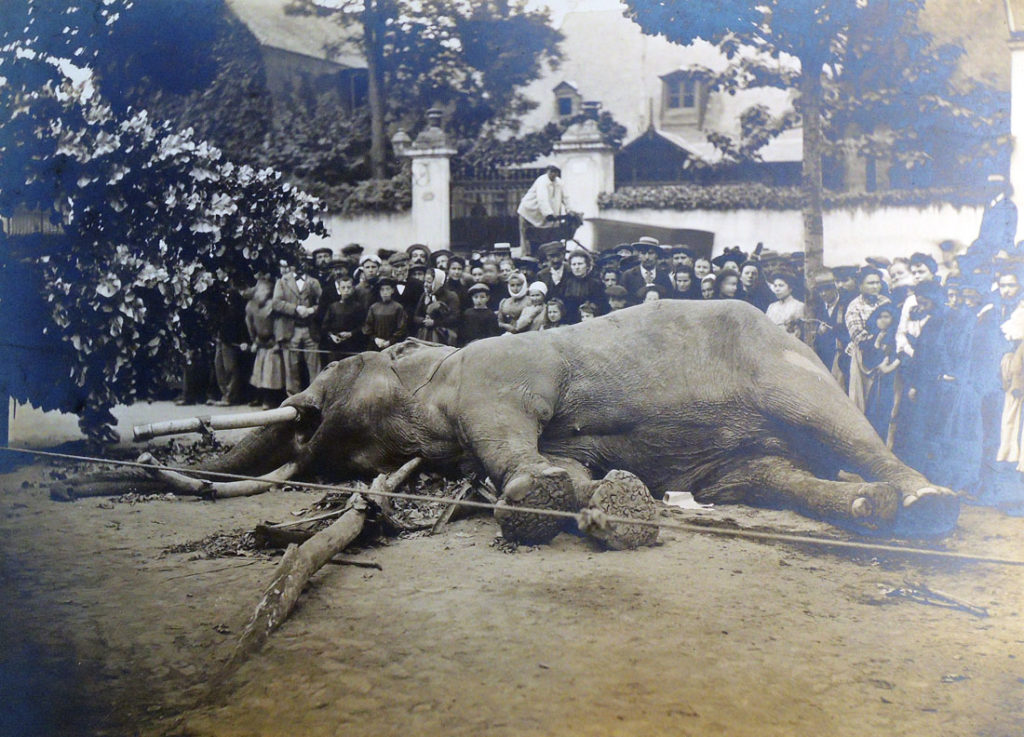

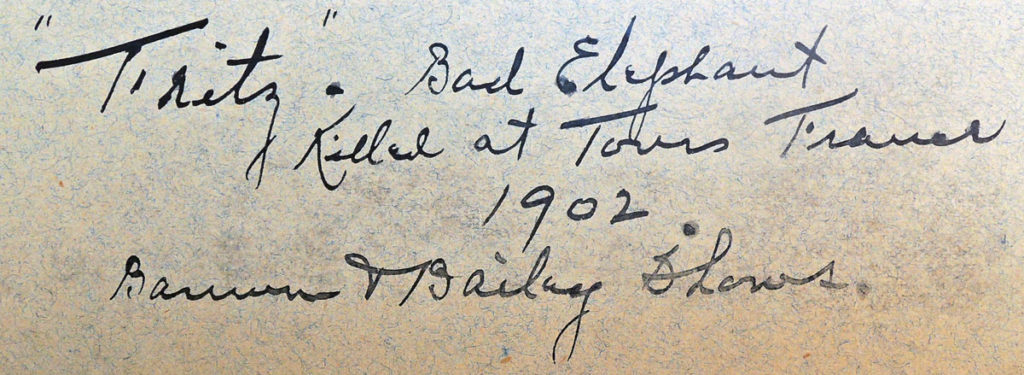

The Graphic Arts Collection holds two composite photographs of circus people. One is organized and indexed. The second, well, the second isn’t. The owner of his own Midwest circus, Charles (Uncle Charley) Andress (1852-1933) was also a circus historian, publishing several articles and photo-essays, including Route Book of Barnum & Bailey [Circus], 1905.

The owner of his own Midwest circus, Charles (Uncle Charley) Andress (1852-1933) was also a circus historian, publishing several articles and photo-essays, including Route Book of Barnum & Bailey [Circus], 1905.