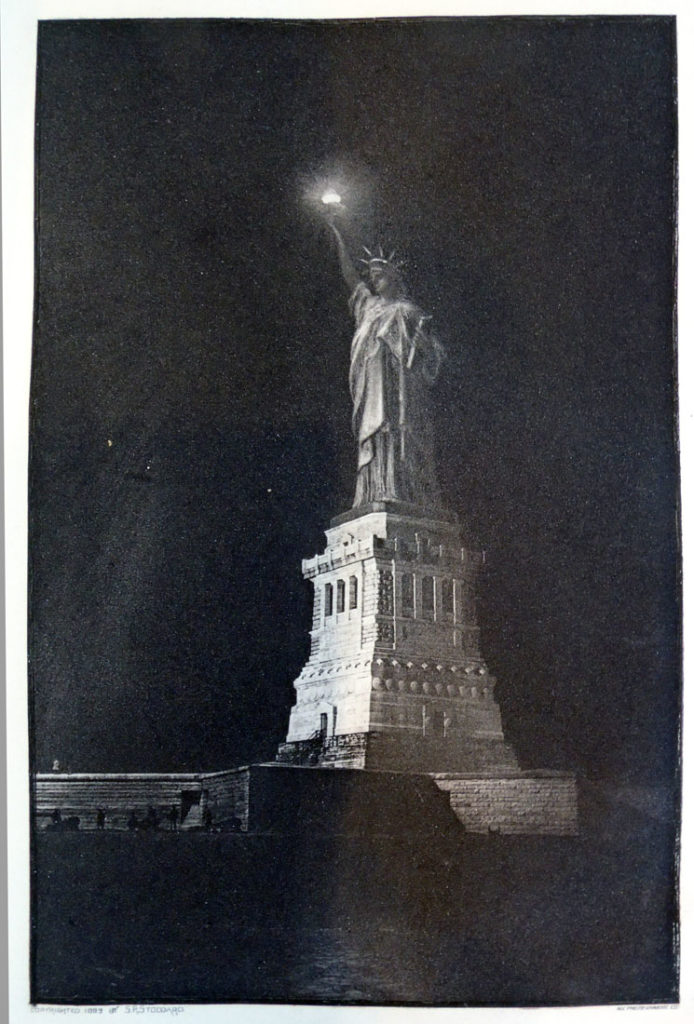

After Seneca Ray Stoddard (1844-1917), Statue of Liberty at Night, 1889. Photogravure. Published in Sun and Shade, vol. 3, no. 25 (September 1890).

After Seneca Ray Stoddard (1844-1917), Statue of Liberty at Night, 1889. Photogravure. Published in Sun and Shade, vol. 3, no. 25 (September 1890).

“Mr. Stoddard employed five cameras on this occasion, stationing them on the Steamboat Pier. A wire was stretched from the torch of the Statue to the mast of a vessel a considerable distance away. Placed on this wire, controlled by a pulley, was a cup containing one and one-half pounds of flash powder; an electric wire was connected with it, and at a given signal the current turned on, by the electrician in charge of the torch, the flash exploded and the exposure made.”

While living in Kilburn Square, Ernest Edwards (1836-1903) recorded his occupation as Heliotyper, having patented his own version of the heliotype or collotype. The Edwards Heliotype Plant employed 72 workers in 1872, making ink prints for such noteworthy projects as Oscar G. Rejlander’s photographs in Darwin’s The Expressions of Emotions in Man and Animals, [Graphic Arts Collection 2003-0902N].

At the age of 36, Edwards left his business to make heliotypes for Osgood and Company in Boston from 1872-1886 but when that firm went bankrupt, Edwards joined Edward L. Wilson (1838-1903) in New York City, where The Philadelphia Photographer was now published as Wilson’s Photographic Magazine. The two men each rented offices at 853 Broadway, off Union Square, and Wilson began highlighting Edwards’s photomechanical prints each month in his magazine.

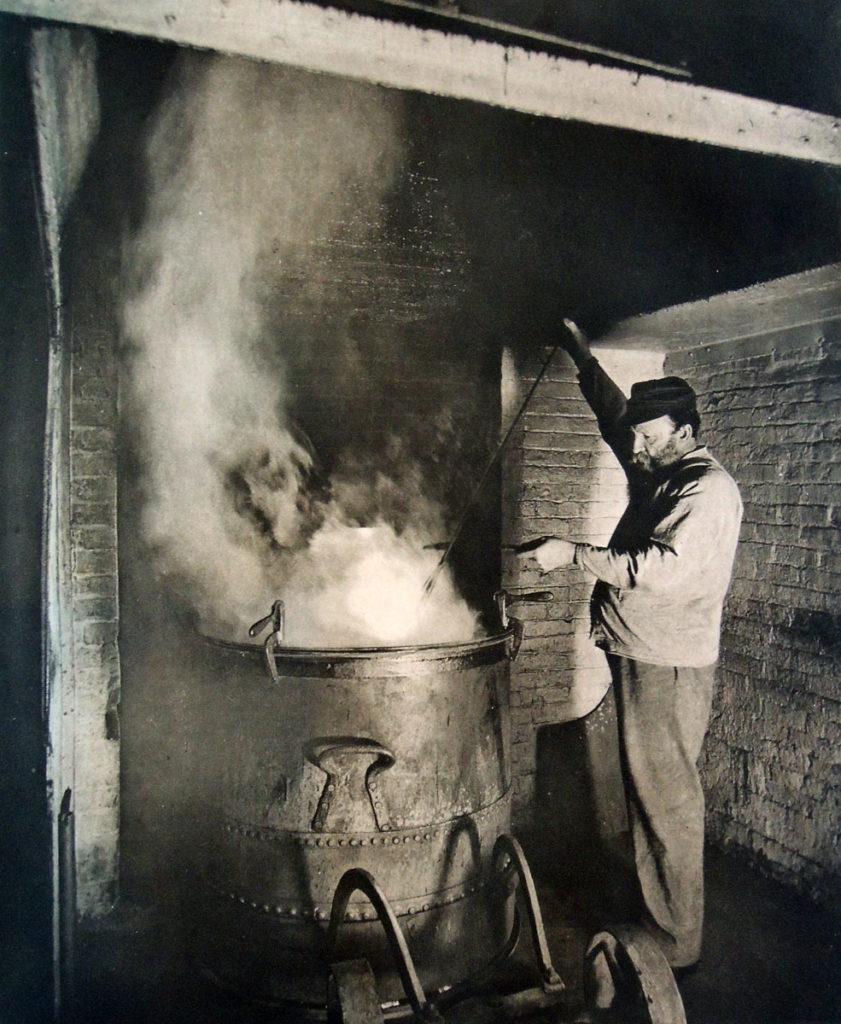

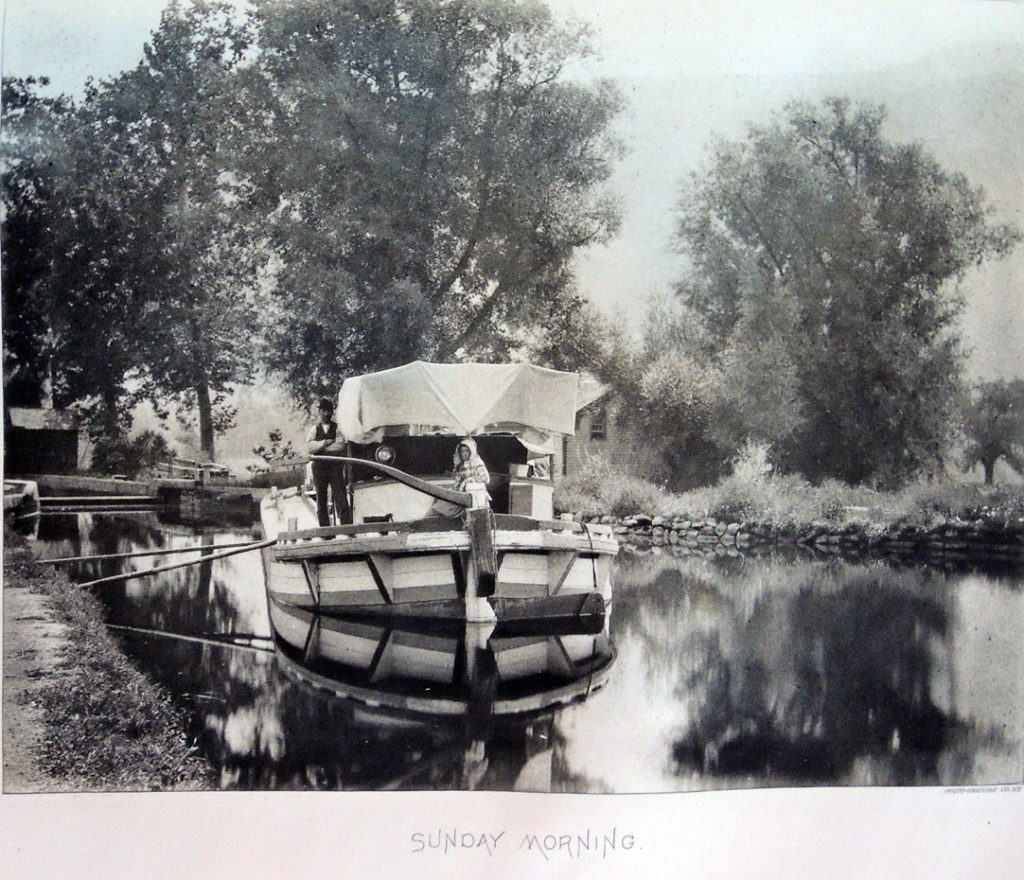

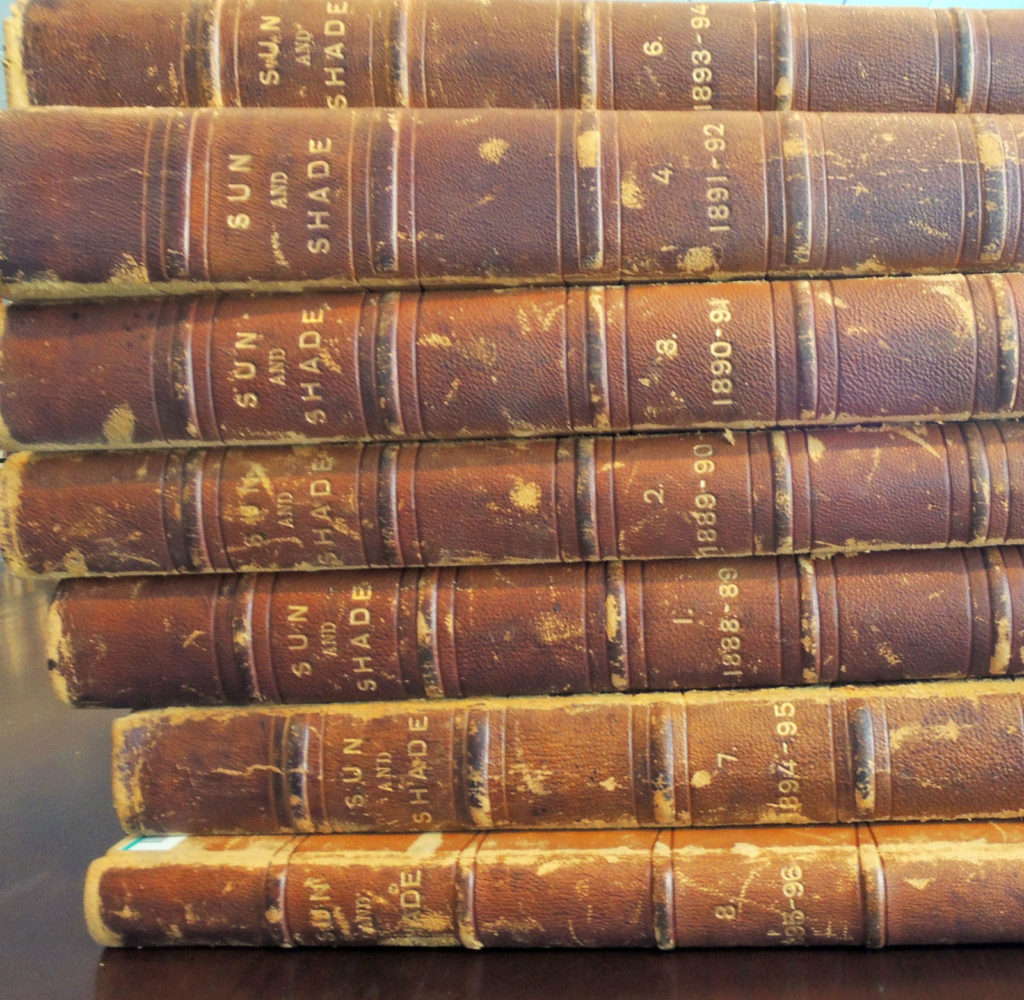

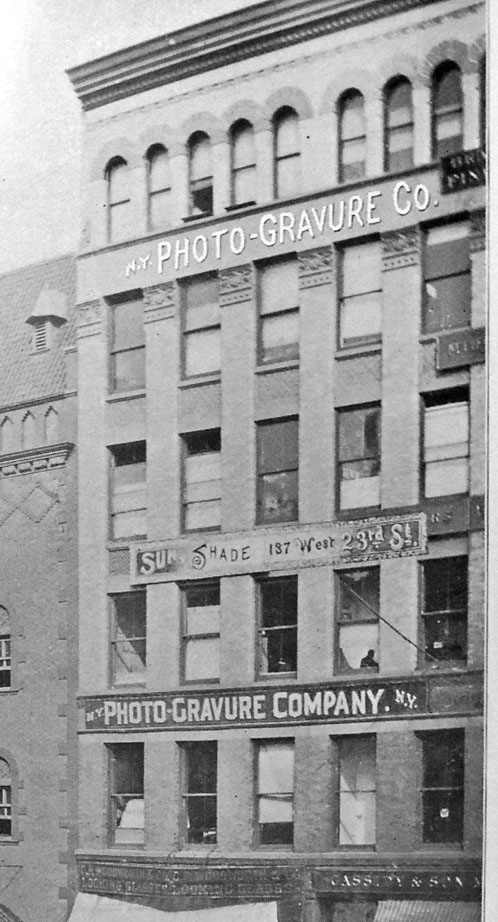

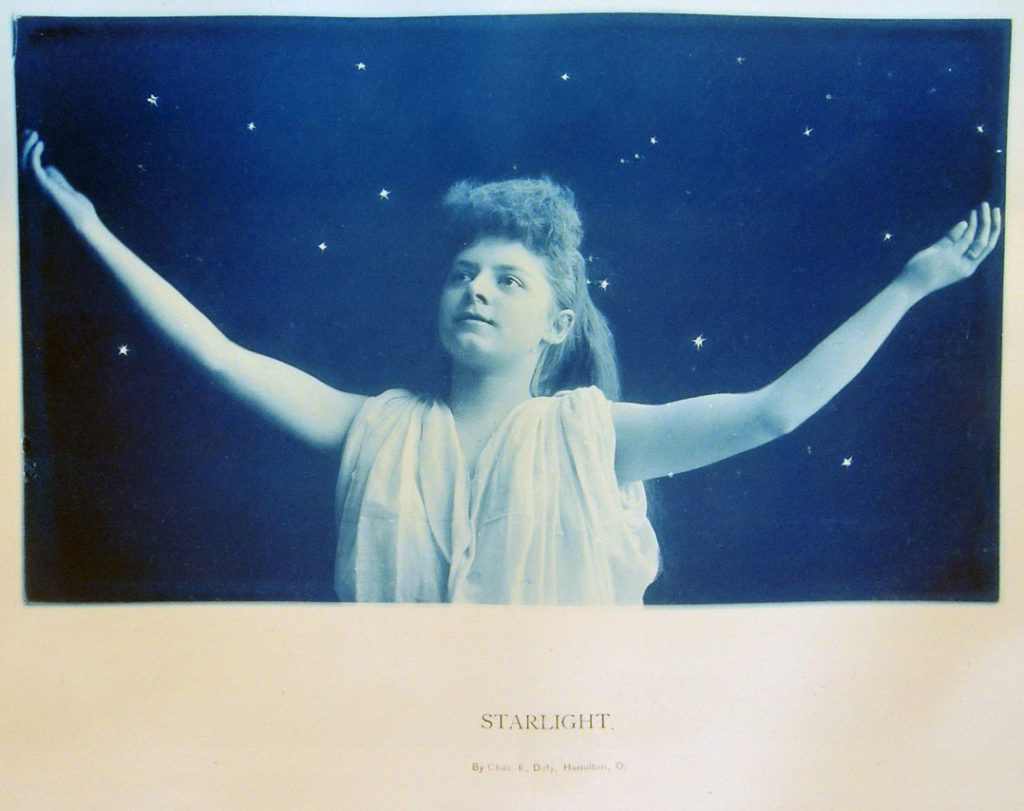

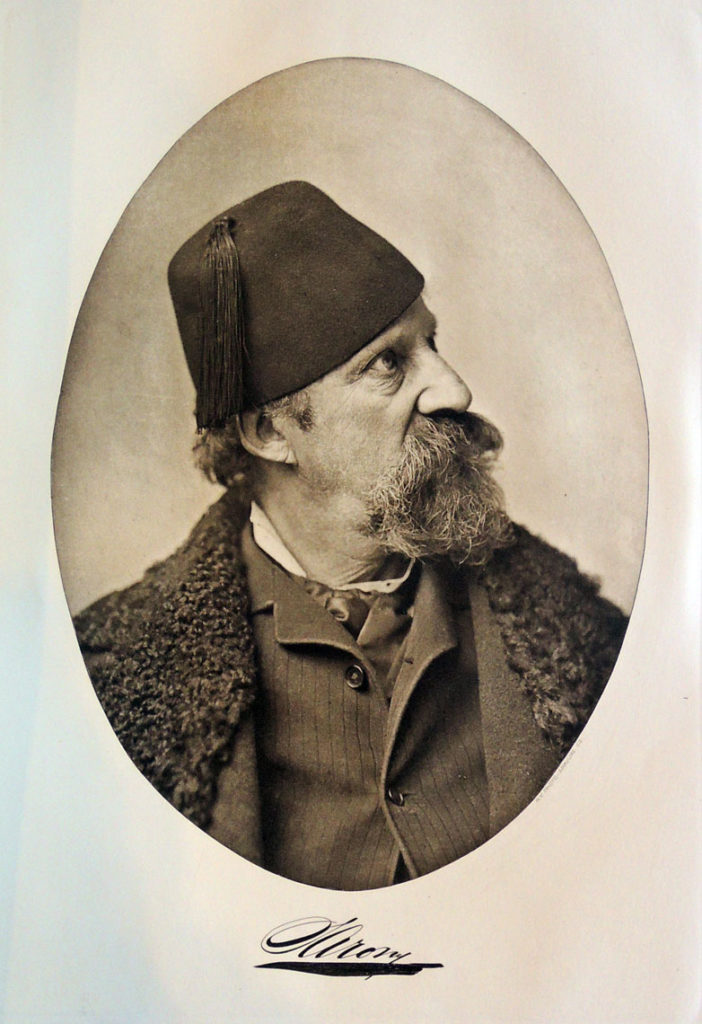

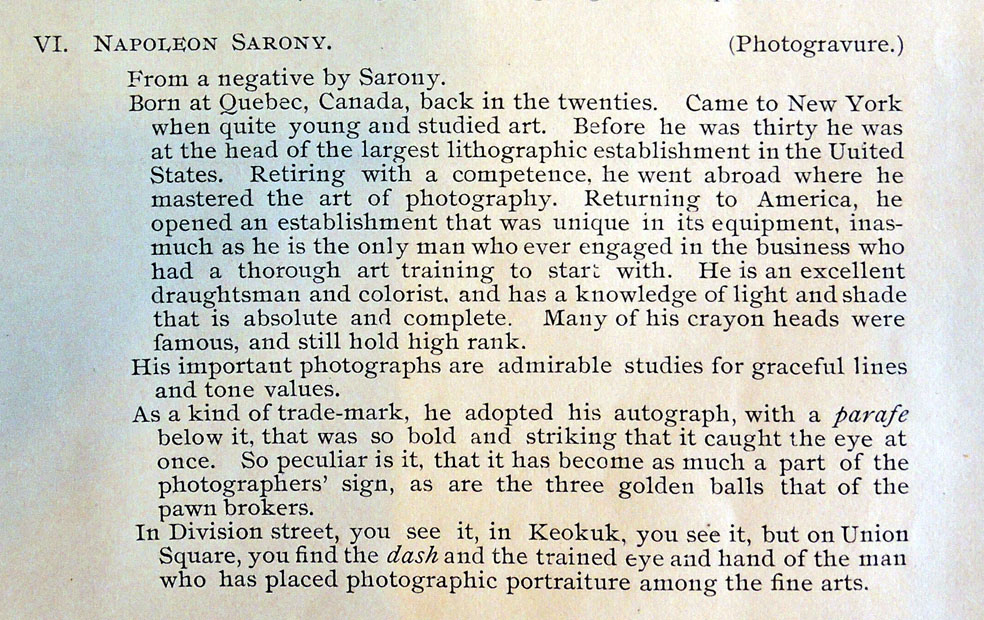

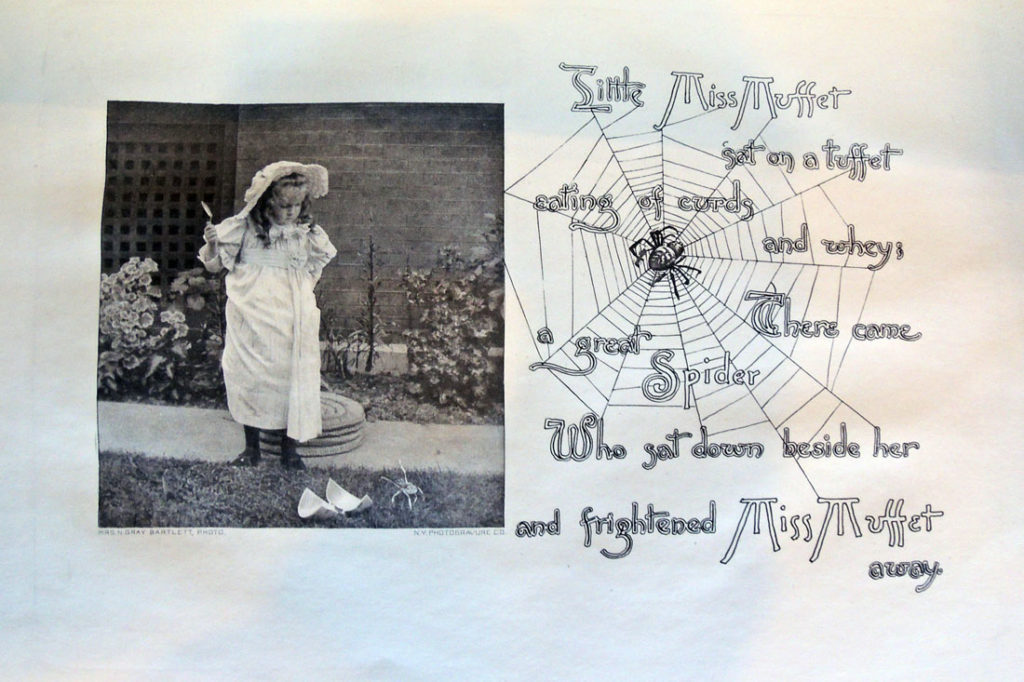

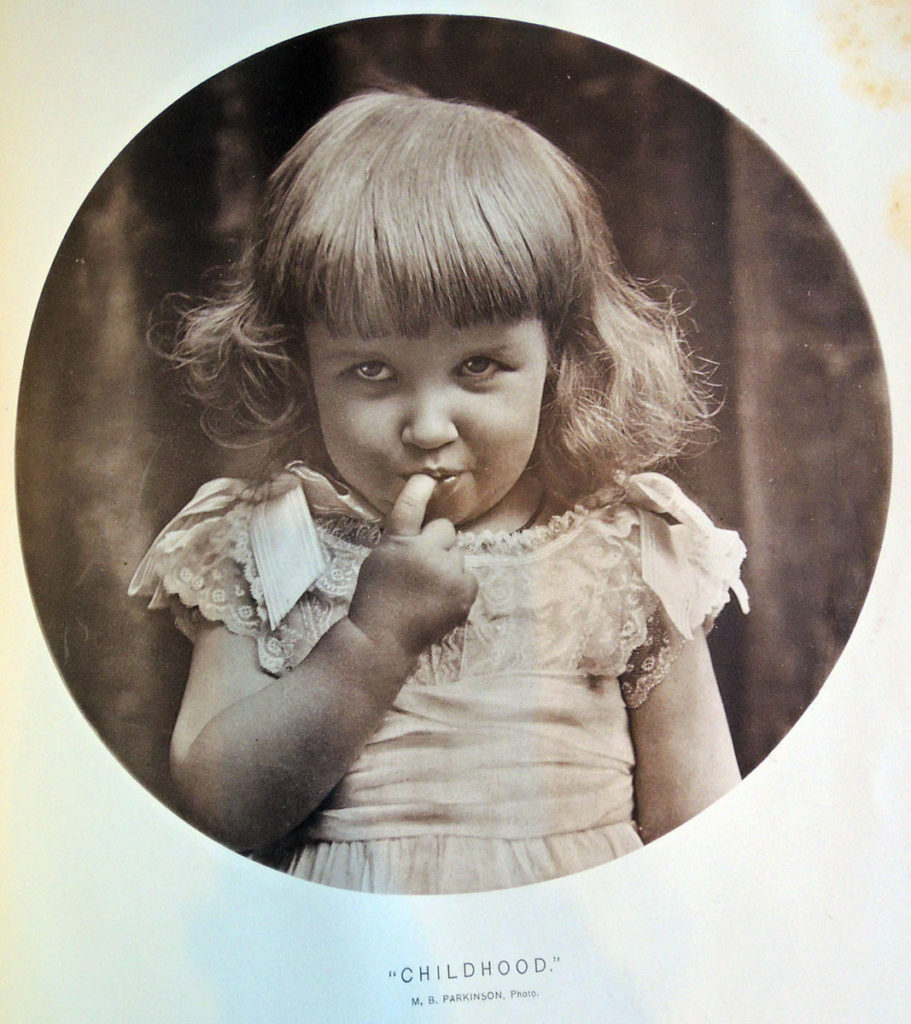

Thanks to wide-spread acclaim and growing demand in his work, Edwards moved again, taking over the entire building at 137 West 23rd Street for his New York Photo-Gravure Company. To further promote his artistic printing, the company launched a luxury magazine, entitled Sun and Shade, a large format monthly comprised of photogravure and photogelatine (collotype) plates “without letterpress.” Each issue featured several important photographers of the day as well as reproductions of fine art.

“A year ago we commenced the publication of our novel venture in journalism Sun and Shade,” wrote Edwards, “a Picture Periodical without letterpress, almost as an experiment, with a modest list of less than fifty subscribers. To-day we are printing an edition of 4,000 copies monthly. A sufficiently convincing proof of the wisdom of our hope that there was room for us.”

“In our rapid growth, the wish has been indicated unmistakably for the higher grade of pictures, and of the higher class—always for quality rather than quantity. Following rather than leading such a wish, we feel that we make no mistake in marking the future career of the magazine to be rather that of an artistic periodical than a photographic record of events.” —Photographic Times and American Photographer, Vol. 19 (1889): 394.

Reviews of the lavish magazine noted in particular that it offered “pictures without text,” and today, we recognize Sun and Shade as the important forerunner of Camera Notes, Camera Work, and later, Life and Look magazines.

“Sun and Shade is evidently meeting with the popularity it so richly deserves, in as much as it is impossible to secure back numbers, and we are told that the publishers in several cases have been obliged to re-issue in order to meet the great demand for certain numbers. —American Journal of Photography, vol. 10 (1889): 189.

Princeton University Library is fortunately to have an almost complete run of Edwards’s journal, with all the plates intact. Here are a few more examples.

Sun & Shade: an Artistic Periodical (New York: New York Photo-gravure Co., 1888/89-1896). 8 v. SA Oversize N1 .S957q.

Pingback: The Kittens are Gone to St. Pauls | Graphic Arts