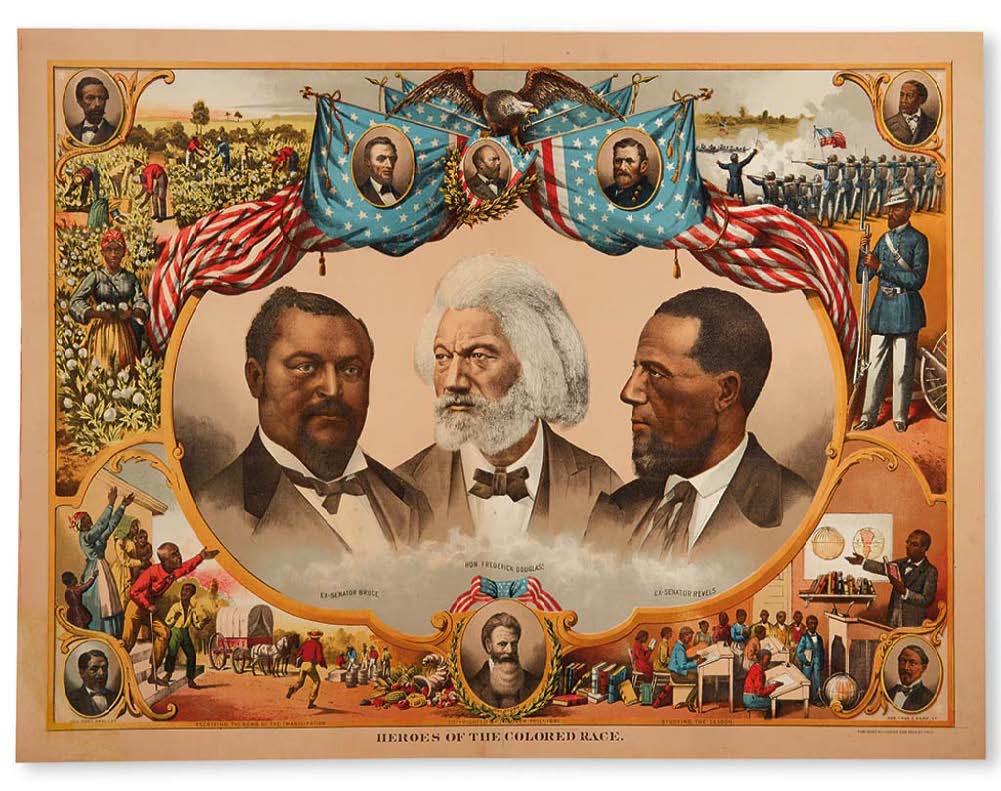

On July 25, 1866, the artist William Marshall wrote to the Atlantic Monthly with information about his new, highly anticipated print.

On July 25, 1866, the artist William Marshall wrote to the Atlantic Monthly with information about his new, highly anticipated print.

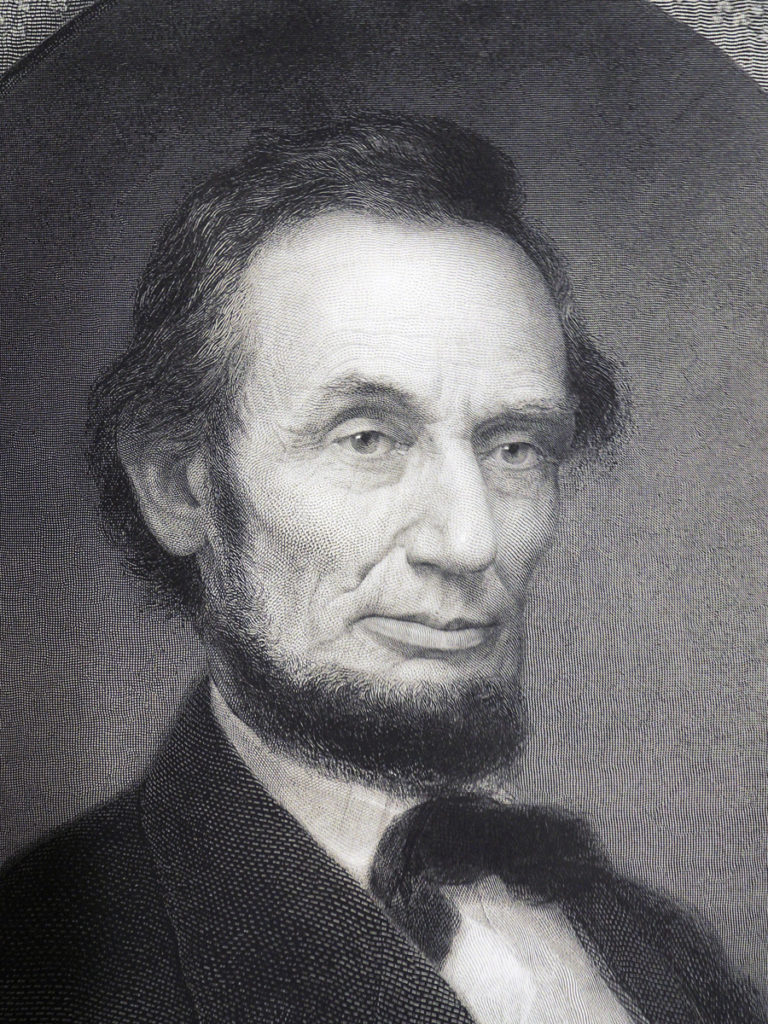

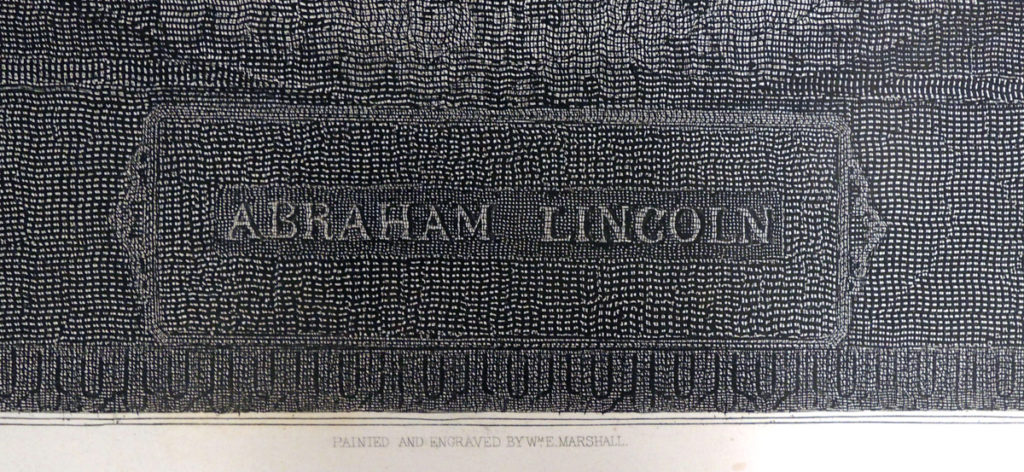

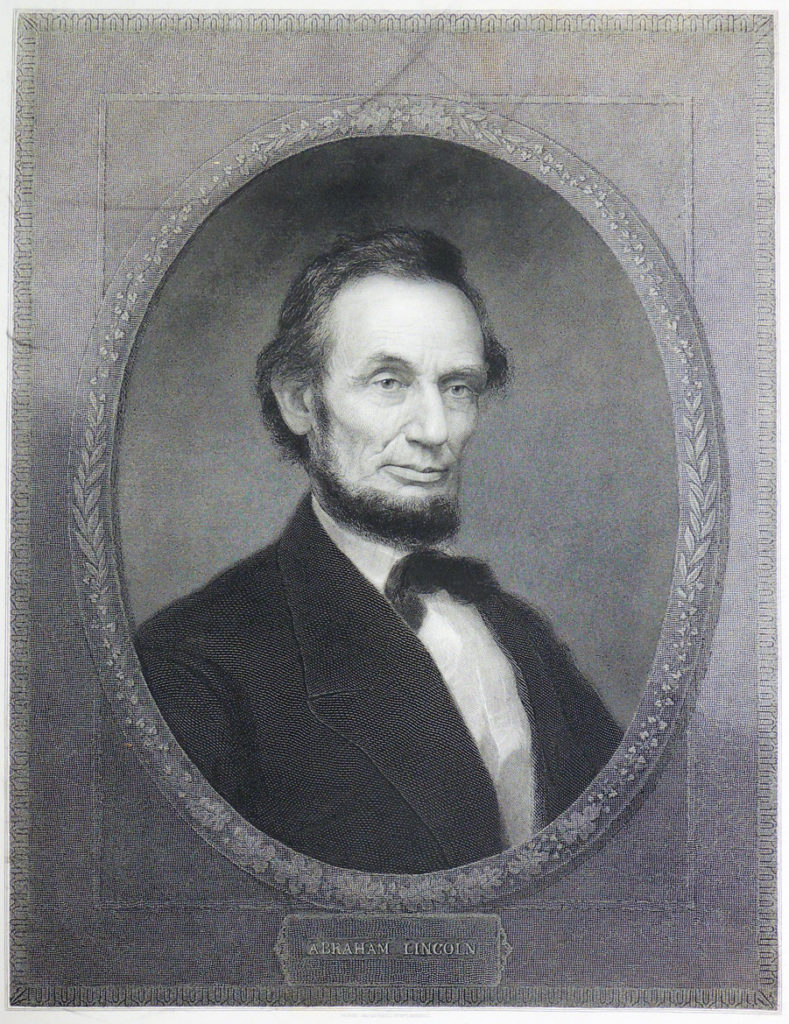

I send you with this a proof of my engraved portrait of President Lincoln, Upon which I have been engaged so long, engraved as you are aware after my own painting. As a work of art, I submit it to yourselves and to the public on its merits. That it is a truthful portrait or Mr. Lincoln, as he appeared in his calm and thoughtful moments, I have the assurance of many who were Ultimately connected with him during hid whole official career, as well as the testimony of others who enjoyed his acquaintance for many years. On this point I would ask your attention to the opinions of Mr. Sumner, Mr. Stanton, Mr. Trumbull, and Mr. Colfajx, contained in the letters which I enclose.

The execution of this portrait has been a pleasant labor to me during the many months I have been engaged upon it; and in executing it, 1 have endeavored not merely to gratify a professional ambition in producing a work of art, but 1 have sought, so far as could be done in one picture, to represent Mr. Lincoln as he was, and as he will be known in the pages of history and biography.”

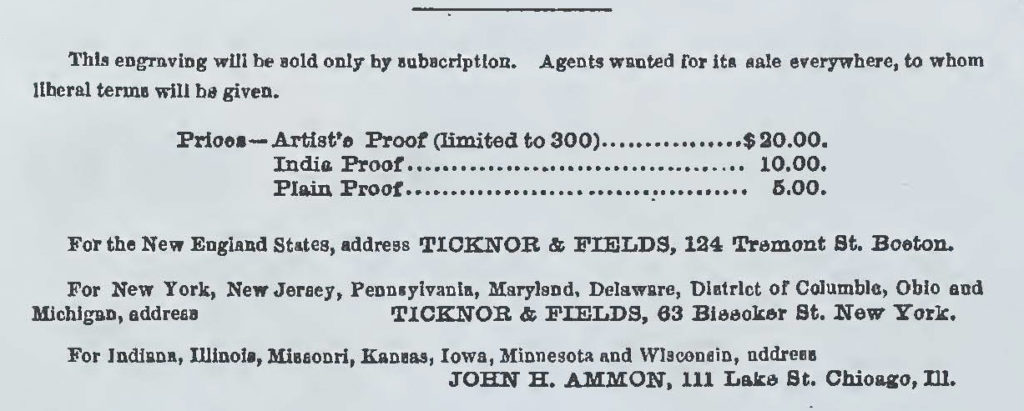

Similar announcement/advertisements were published in magazines and newspapers throughout the United States. Sold by subscription, the engraving was offered on various papers, with no limit to the number of plain proofs that would be pulled.

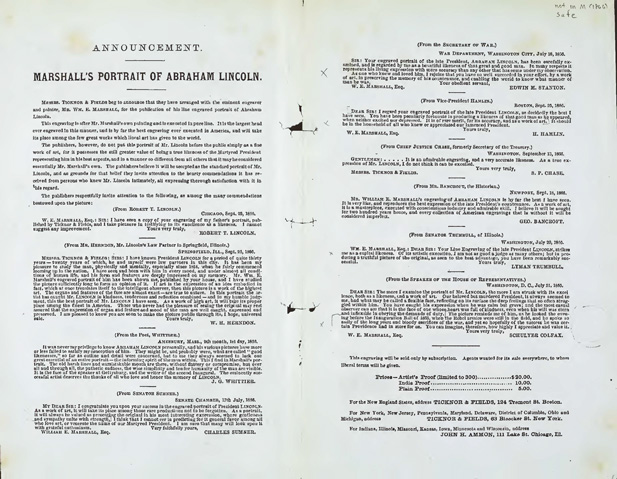

In some places, Marshall and his publishers purchased two full pages to include endorsements from Lincoln family members and colleagues. The advertisement below boasts letters from Robert T. Lincoln, William H. Herndon, John Greenleaf Whittier, Charles Sumner, Edwin M. Stanton, Hannibal Hamlin, Salmon P. Chase, George Bancroft, Lyman Trumbull, and Schuyler Colfax, all praising Marshall’s work.

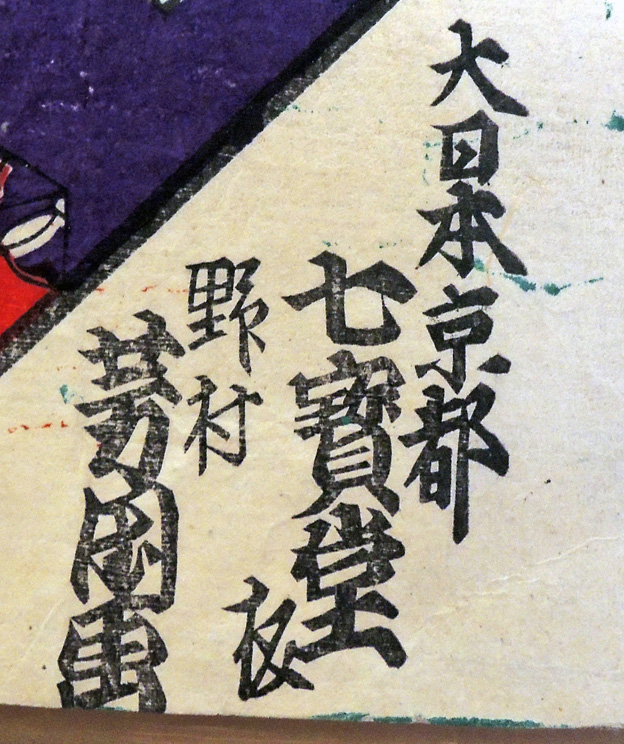

William Edgar Marshall (1837-1906), Abraham Lincoln, 1866. Engraving. Gift of John Douglas Gordon, Class of 1905. Graphic Arts collection GA 2008.00294

Signed and dated in plate, l.c.: ‘Painted & Engraved by Wm. E. Marshall // Entered According to Act of Congress in the Year 1866 by Wm. E. Marshall in the Clerks Office of the District Court of the United States for the Southern District of New York.