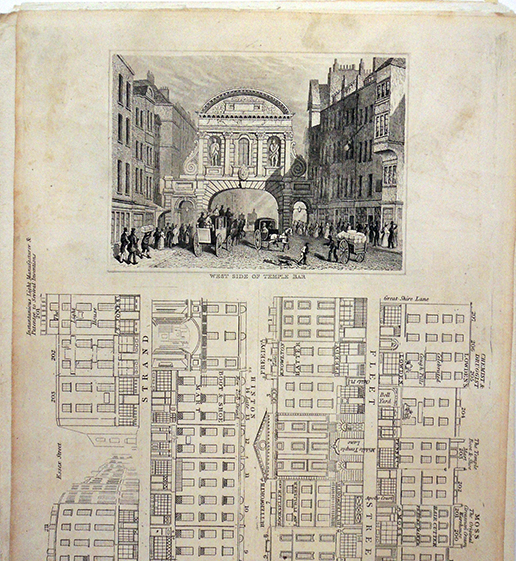

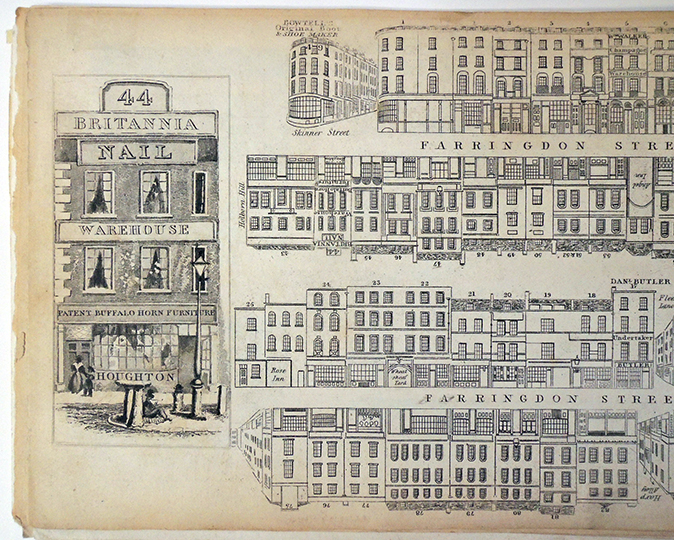

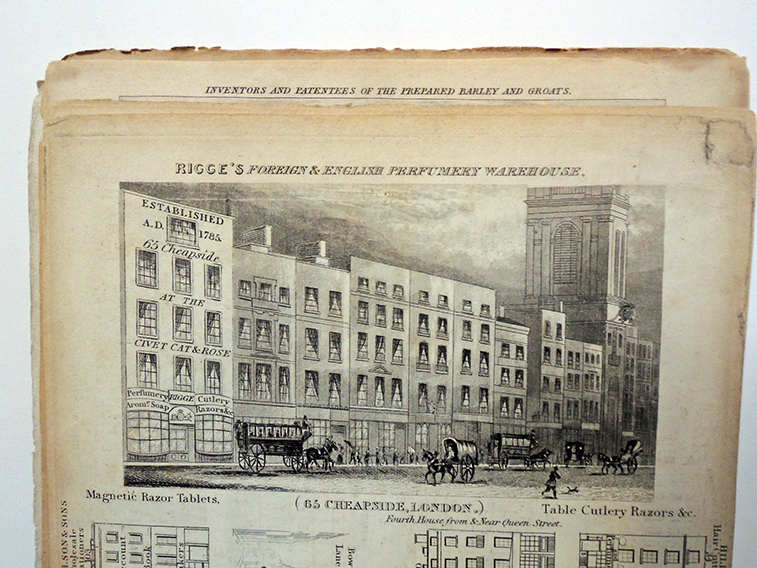

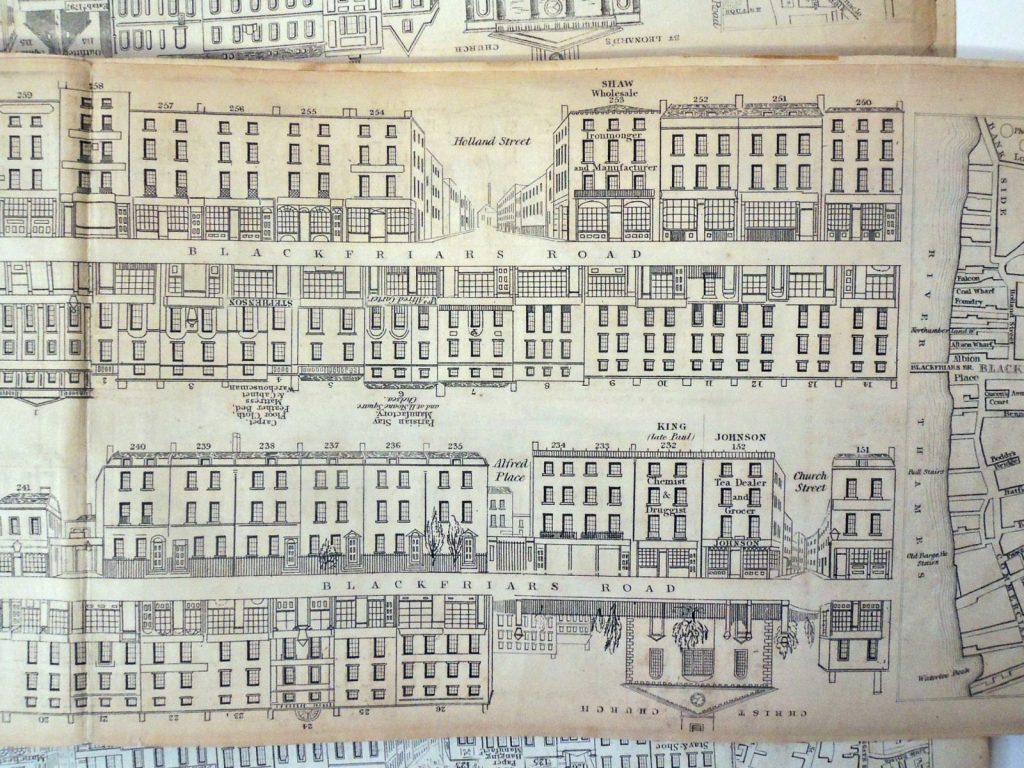

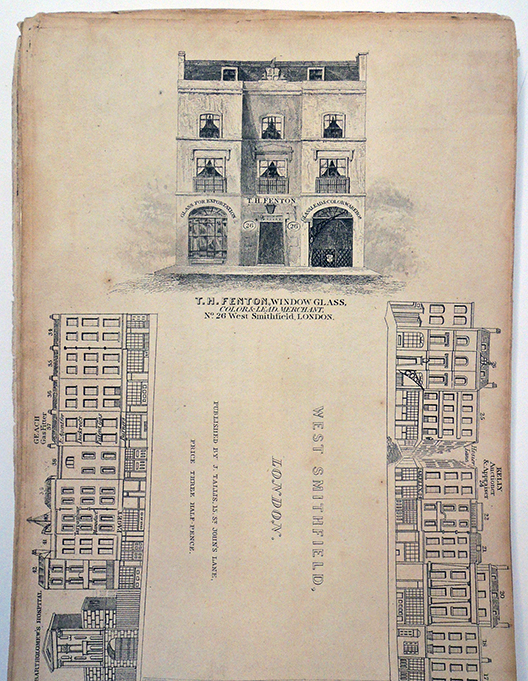

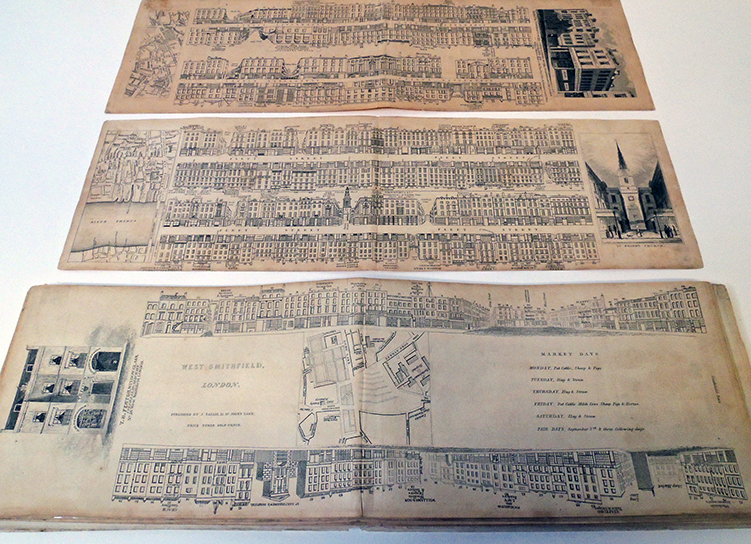

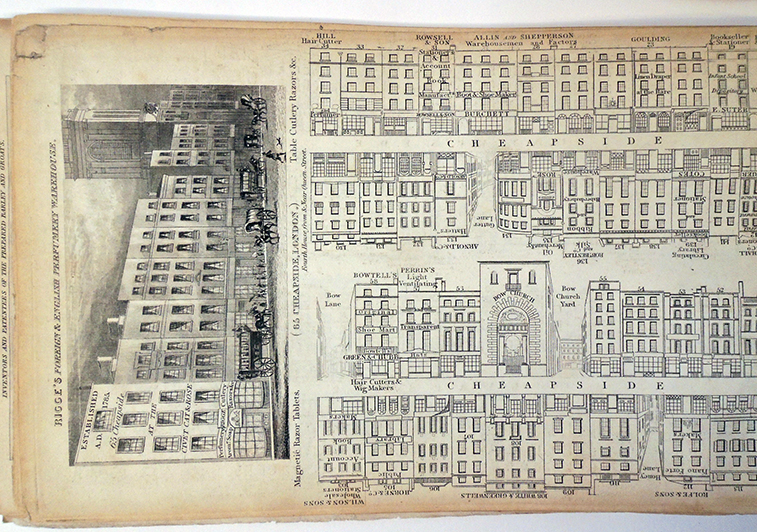

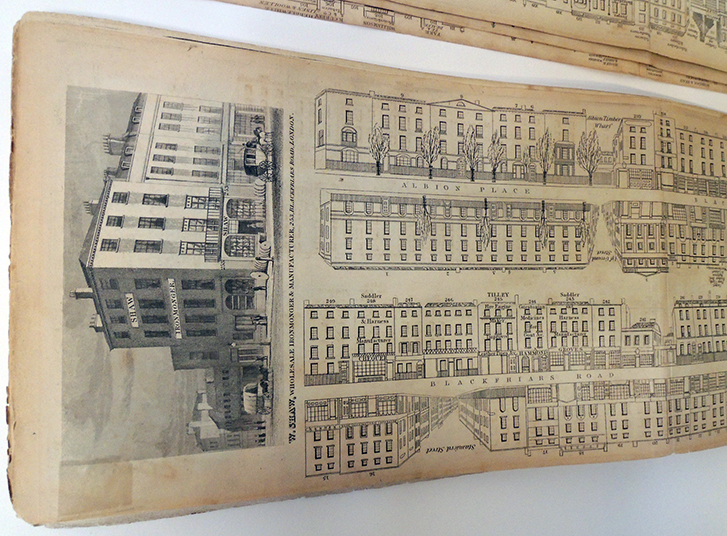

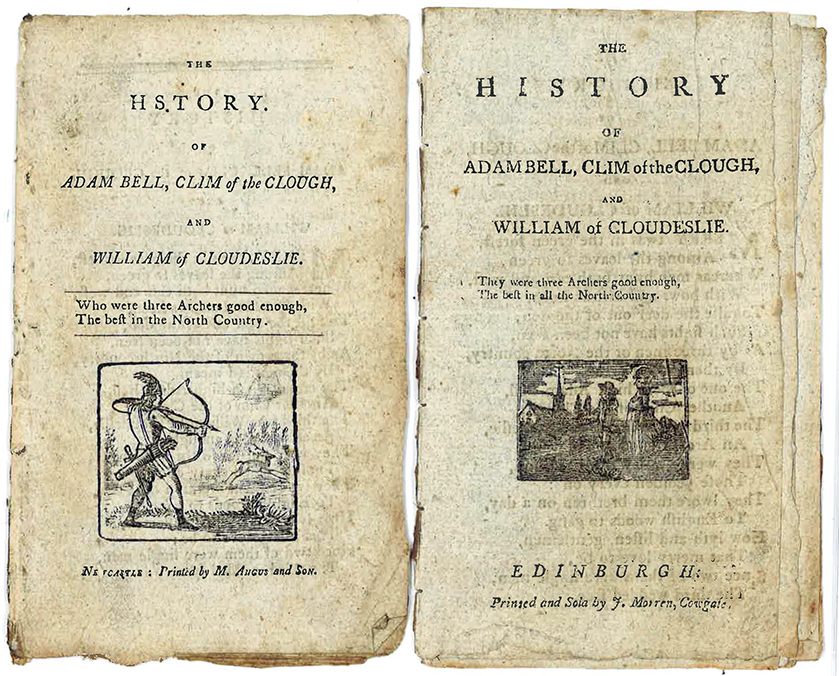

Thanks to a deposit by Bruce C. Willsie ’86, the Graphic Arts Collection now holds 51 of the 88 separate engravings covering 74 London streets published by John Tallis (1818-1876) from 1838 to 1840. Exceptionally rare, these unbound prints were originally published in parts and only later as a bound set. Tallis promised that his directory to the buildings and businesses on each street would be corrected and updated every month. The elaborate title explains it all:

Tallis’s London Street Views, Upwards of One Hundred Buildings in Each Number, Elegantly Engraved on Steel; with a Commercial Directory Corrected Every Month, The Whole Forming a Complete Stranger’s Guide Through London, and by Reference, from the Directory to the Engraving, Will Be Seen All The Public Buildings, Places of Amusement, Tradesmen’s Shops, Name and Trade of Every Occupant, &c. &c. To Which Is Added an Index Map of the Streets, From a New Actual Survey, Now Making, At a Cost of Upwards of One Thousand Pounds; and a Faithful History and Description of Every Object Worthy of Notice, Intended To Assist Strangers Visiting the Metropolis, Through All the Mazes Without a Guide. London: published by John Tallis, 15, St. John’s Lane, St. John’s Gate; and regularity kept by al booksellers and toy shops, in England, Wales, Ireland, and Scotland. Each street may be had separately.

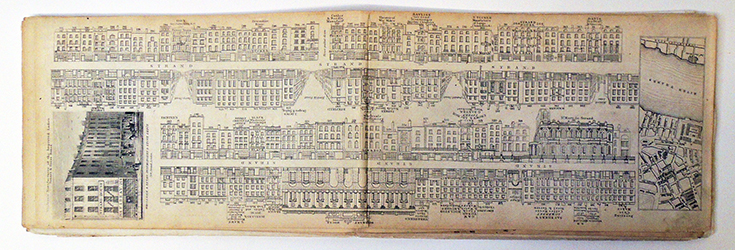

The narrow format made each sheet easy to fold and carry in your pocket for onsite reference, but may also explain their scarcity today. The guides were used so frequently, they eventually fell apart and were discarded.

Each view on two attached sheets, offers both sides of a street, along with one fully engraved and aquatinted building and a map of the area at either end. One typically sold for 1½d. Owners paid extra to have the name of their business engraved over the building or featured at the end of the sheet.

Read more: Alison O’Byrne & Jon Stobart (2017) “Introduction: Roundtable on John Tallis’s London Street Views (1838–1840),” Journal of Victorian Culture, 22:3, 287-296, DOI: 10.1080/13555502.2017.1327196

For a digital view of Tallis’s Streets, see: https://www.romanticlondon.org/tallis-street-views/#14/51.5151/-0.1169. The map here shows the locations of the Street Views depicted; each marker is placed at the center of the appropriate plate. For more on the Street Views, see the Museum of London’s project or the London Topographical Society’s publications on the subject.