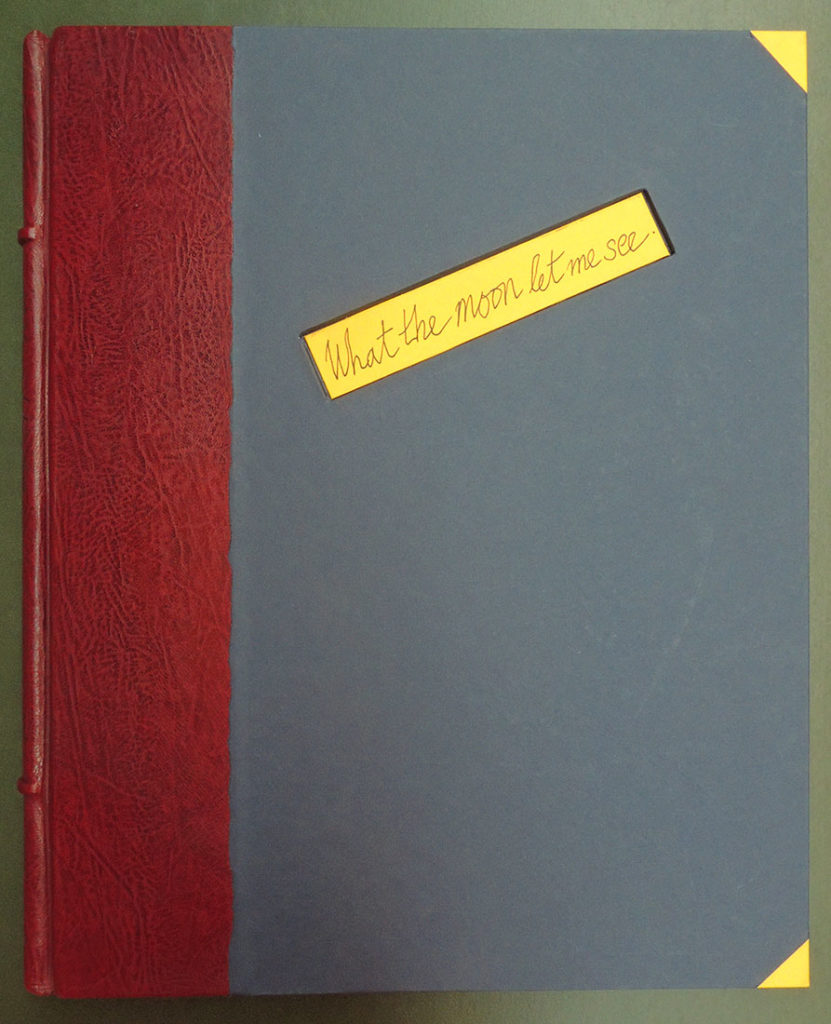

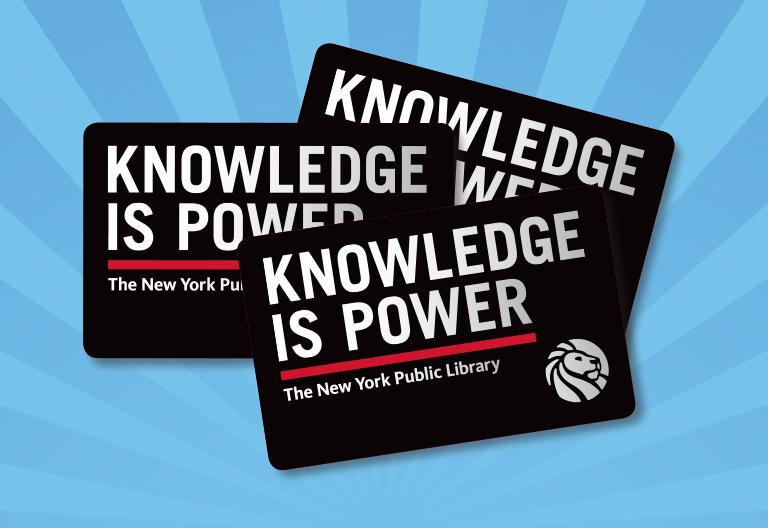

Beginning today the New York Public Library is offering a Special Limited Edition library card that reads: Knowledge Is Power, available only for a limited time (or while supplies last). The edition is 70,000.  “Apply in person at your local NYPL branch, or sign up online and visit your local branch quickly to validate and pick up your Special Edition card before they run out. Knowledge Is Power cards are free for new cardholders. Library card applicants must show proof that you live, work, attend school, or pay property taxes in New York State.”

“Apply in person at your local NYPL branch, or sign up online and visit your local branch quickly to validate and pick up your Special Edition card before they run out. Knowledge Is Power cards are free for new cardholders. Library card applicants must show proof that you live, work, attend school, or pay property taxes in New York State.”

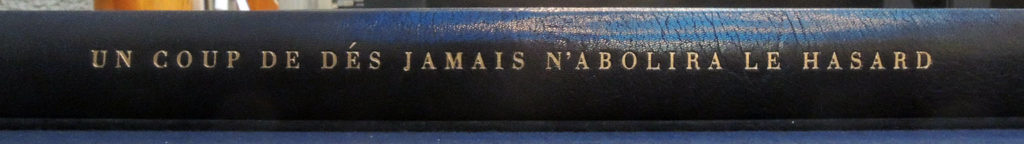

This led to the question of just how big an edition can be and still be defined as a special limited edition? In 1896, Martha Finley’s Elsie Dinsmore was published by Grosset & Dunlap in New York, in a special limited edition of 100,000 copies. Today, it is also possible to read it online, with unlimited access to the special limited edition.

According to library records Monbusho’s Kankyo shogaku tokuhon maki 1 (Primary reader, vol. 1) was published in 1873 in an edition “Limited to 5,000,000 copies.” (Cotsen Children’s Library Pams / NR / Japanese / Box 135 65143). This is not a typo.

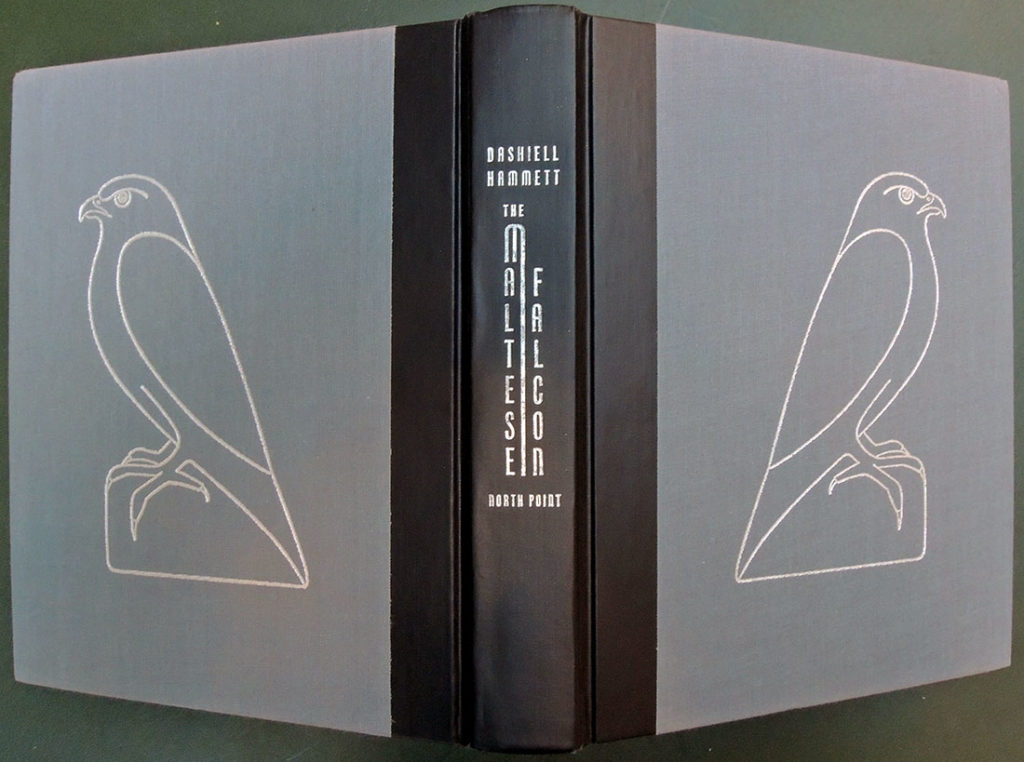

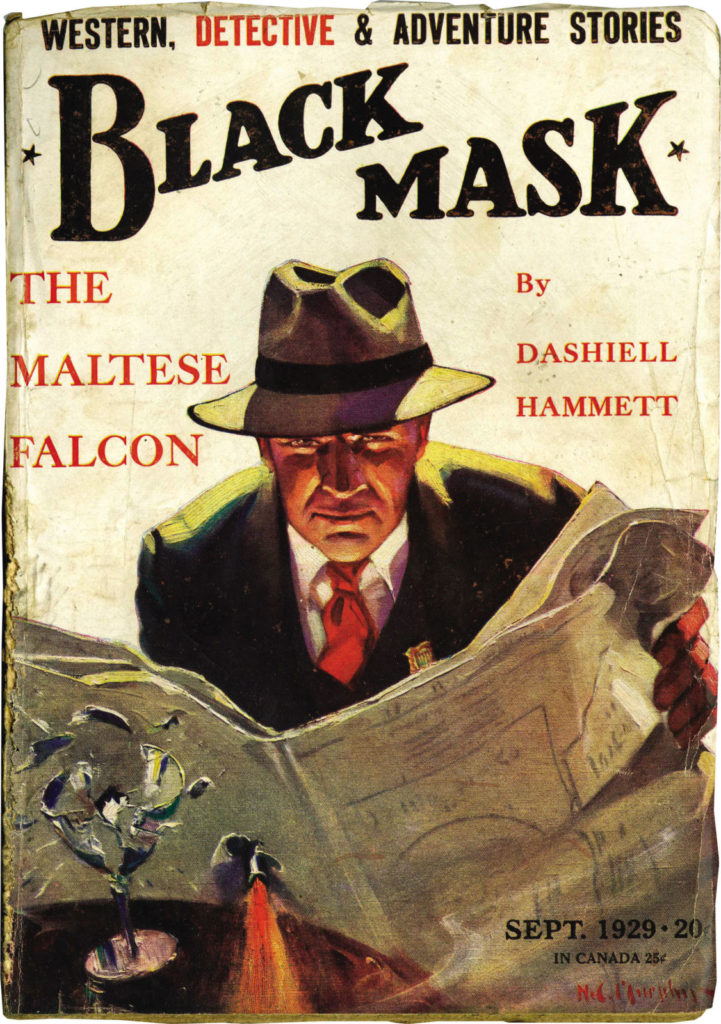

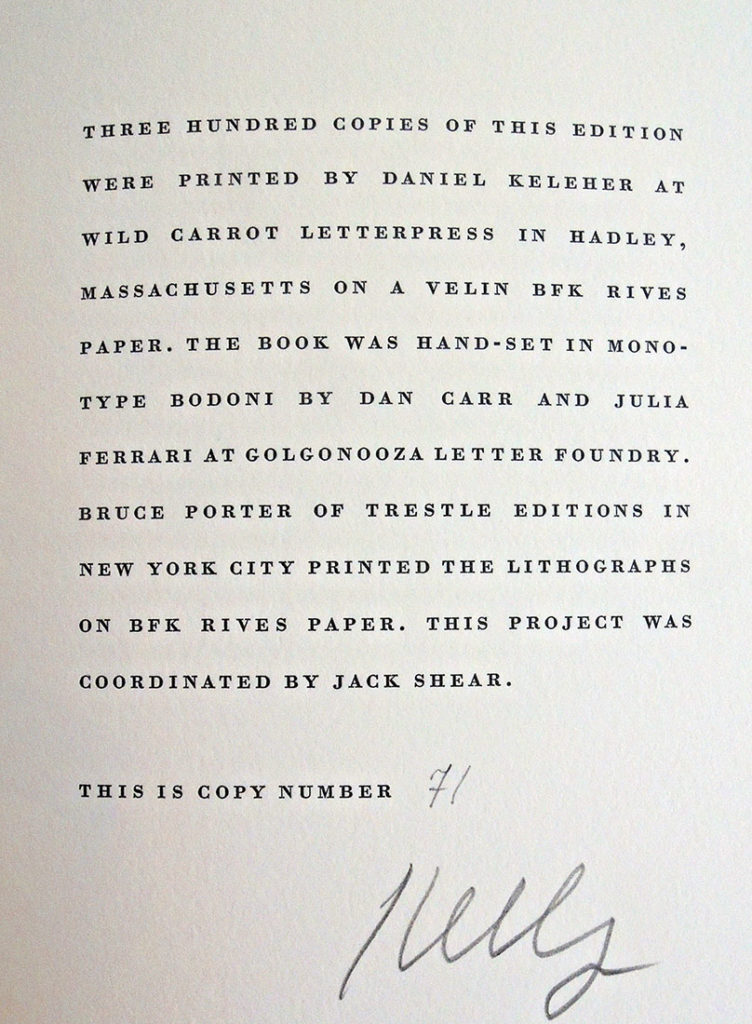

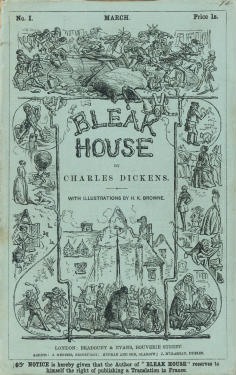

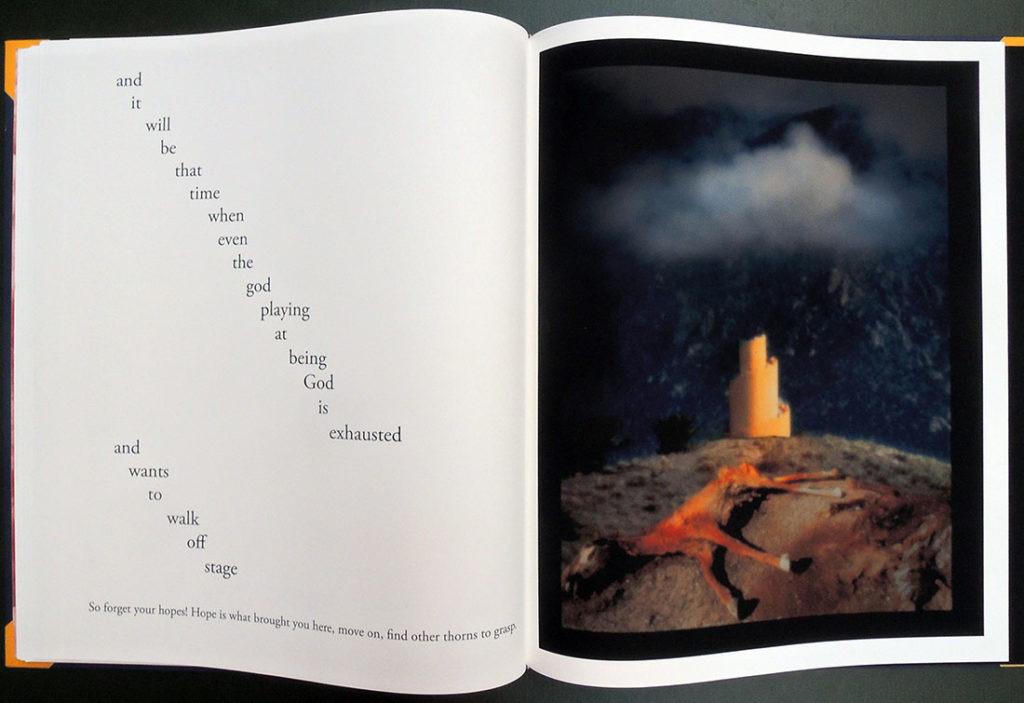

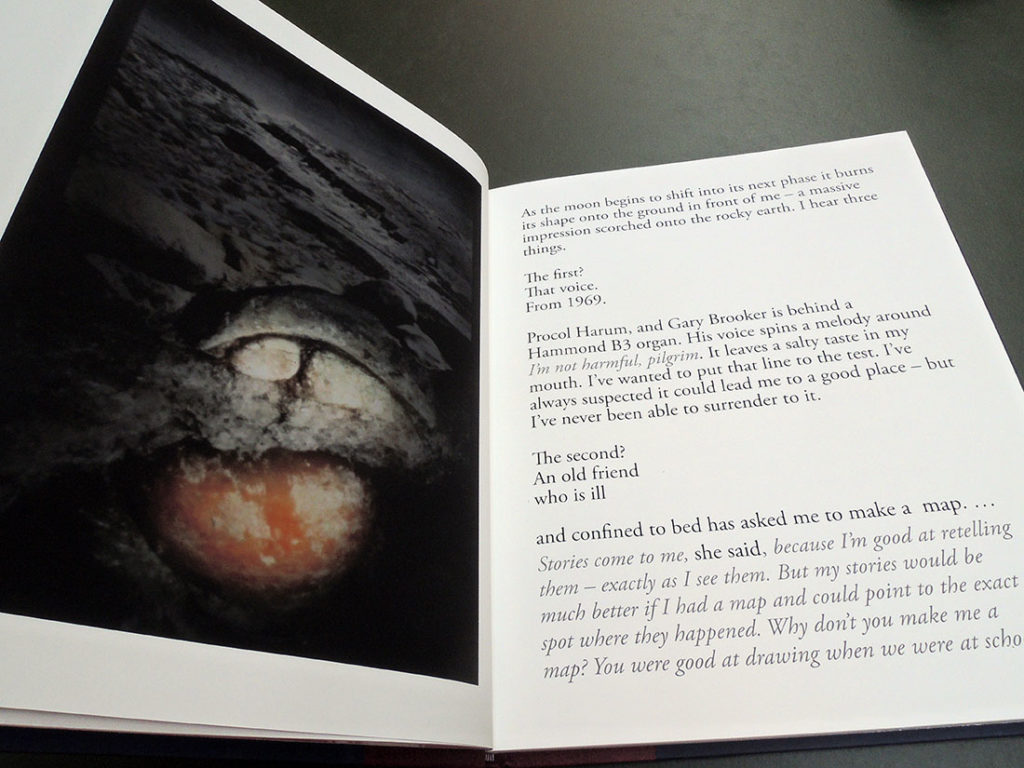

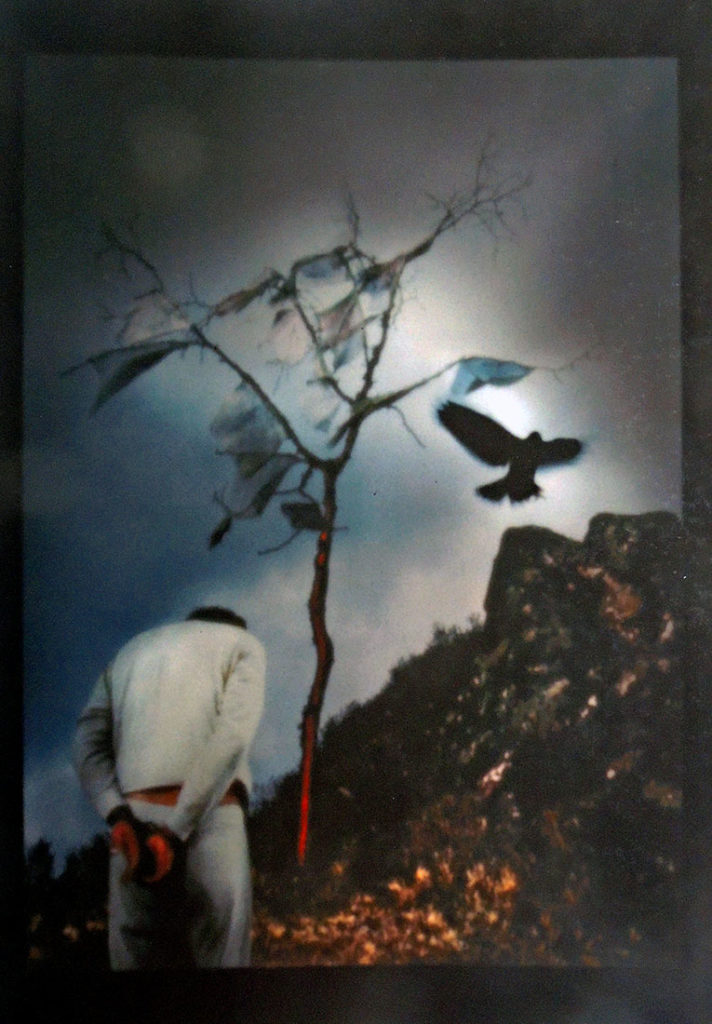

Ed Templeton and Deanna Templeton’s modern photobook Contemporary Suburbium (2017) was released in a “Limited edition of 2,000 copies” (Marquand Library N7433.4.T47 C68 2017). Alfredo Jaar’s homage to John Cage on the occasion of the Cage centennial, entitled Otros piensan = outros pensam, was limited to 1,000 copies, as was Victor Hugo’s Poems (New York: F. DeFau & Co., 1888), available on open shelves or through interlibrary loan. Charles Kingsley’s Alton Locke, Tailor and Poet (New York, J. F. Taylor and Company, 1899) was a “Limited edition of 1,000 copies” although dozens of other editions were also available at the time (PR4842 .xA4 1899). You can undoubtedly think of many other examples.

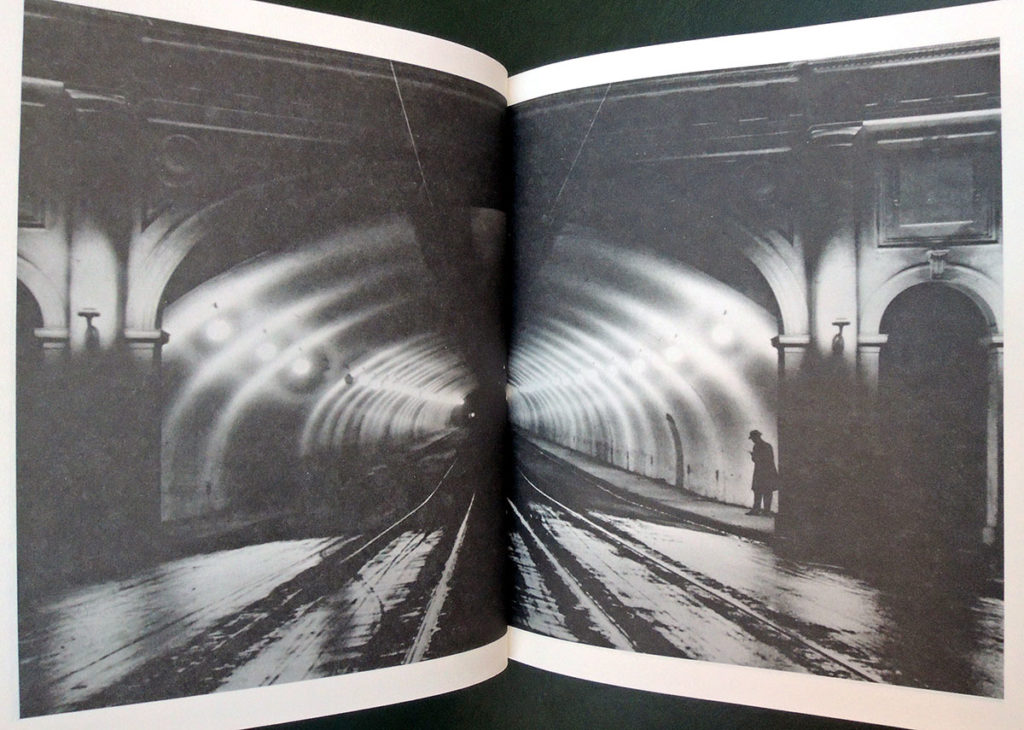

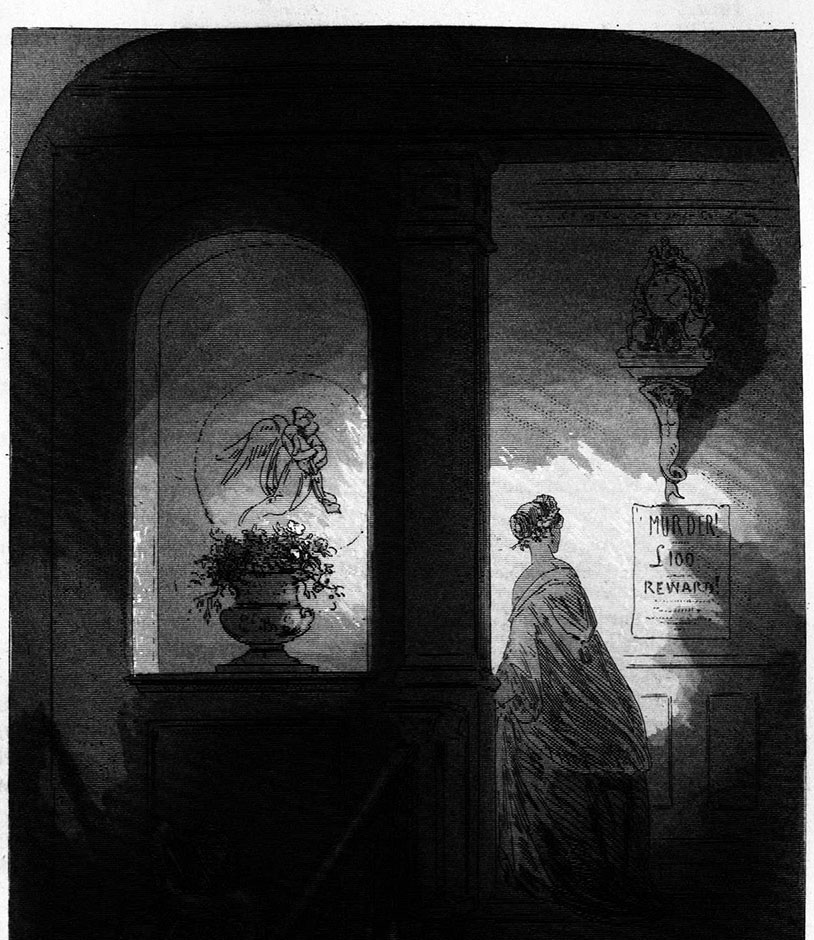

Christian Marclay’s film The Clock was produced in a limited edition of six copies and two artist’s proofs. Five are in public institutions although it can only be played at one location at a time. “When I first started on this project, I thought it would become a public art piece,” Marclay told a New Yorker writer. “I thought, What a great thing, to be in a train station waiting for a train and being able to watch a movie. It would inform you what time it was, and at the same time entertain you. But I realized it was impossible—there’s lighting issues, sound issues, you have to hear the public-address system.”

Christian Marclay’s film The Clock was produced in a limited edition of six copies and two artist’s proofs. Five are in public institutions although it can only be played at one location at a time. “When I first started on this project, I thought it would become a public art piece,” Marclay told a New Yorker writer. “I thought, What a great thing, to be in a train station waiting for a train and being able to watch a movie. It would inform you what time it was, and at the same time entertain you. But I realized it was impossible—there’s lighting issues, sound issues, you have to hear the public-address system.”

Very few rare book glossaries include a mention of “Limited edition.” The International League of Antiquarian Booksellers notes:

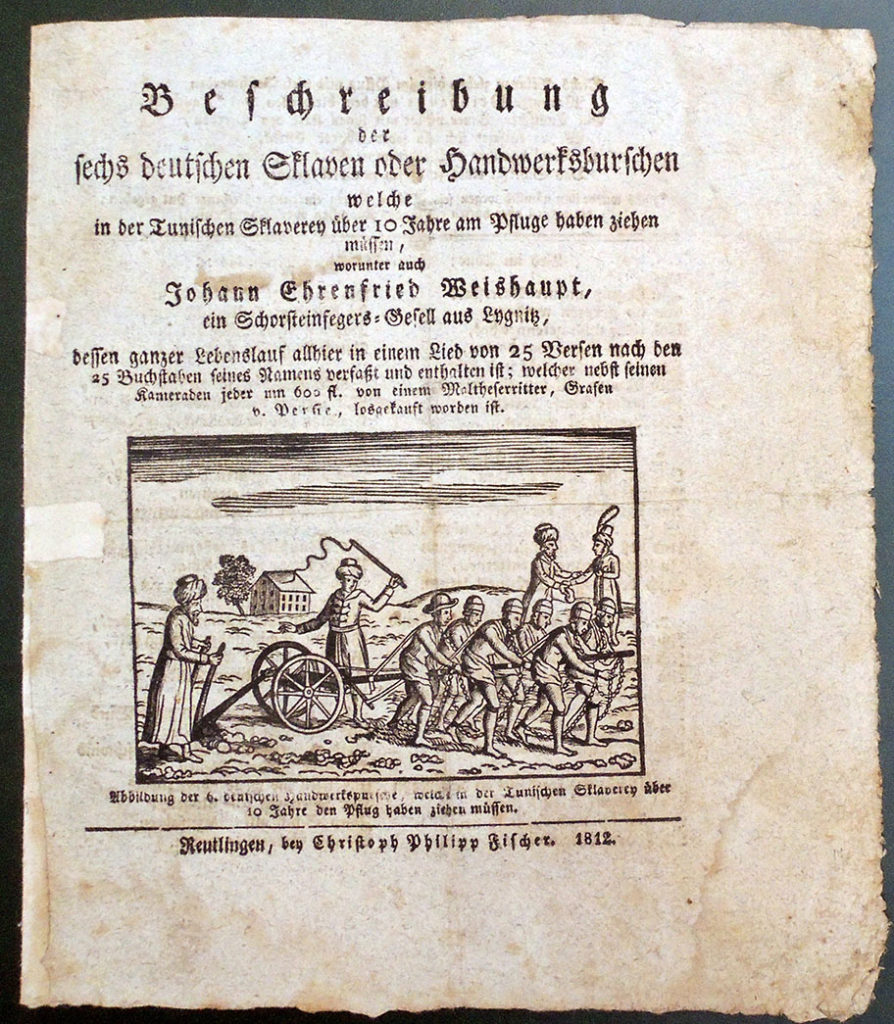

“Book intended to have a finite number of copies, usually intended as a collectible or artificial “rarity.” Often each volume in the edition is supplied with a specific number, and can be signed by the author, artist, binder, etc. Most limited editions have a limitation statement that elaborates on the wonderment of the volume in question. Some less than scrupulous publisher’s will issue editions limited to the number of copies that they can sell, with the limitation proclaimed, but the number not specified.

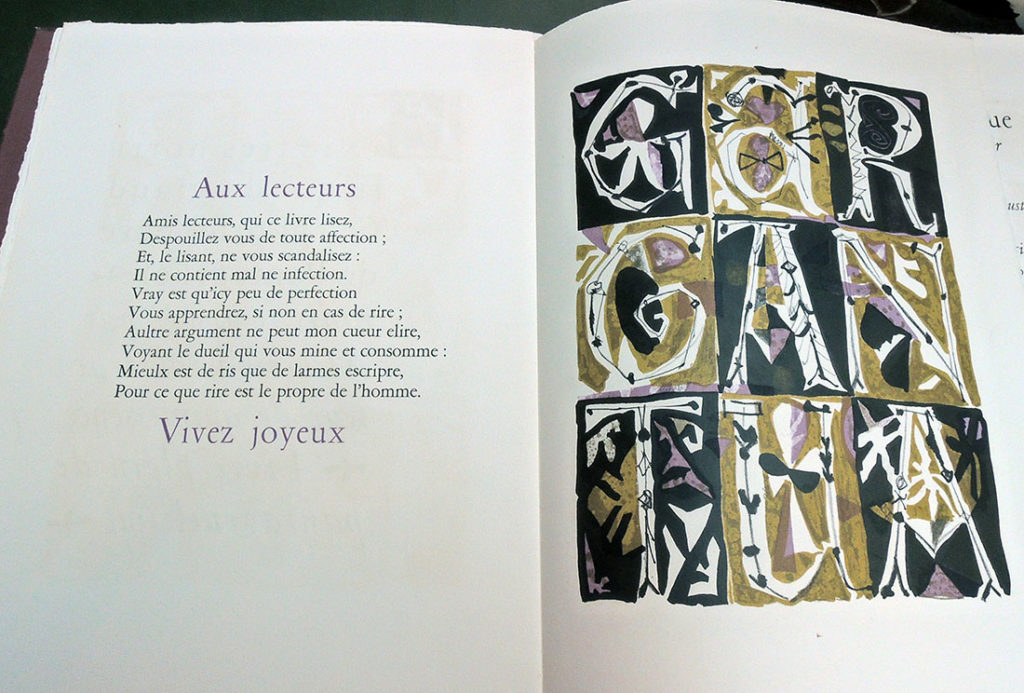

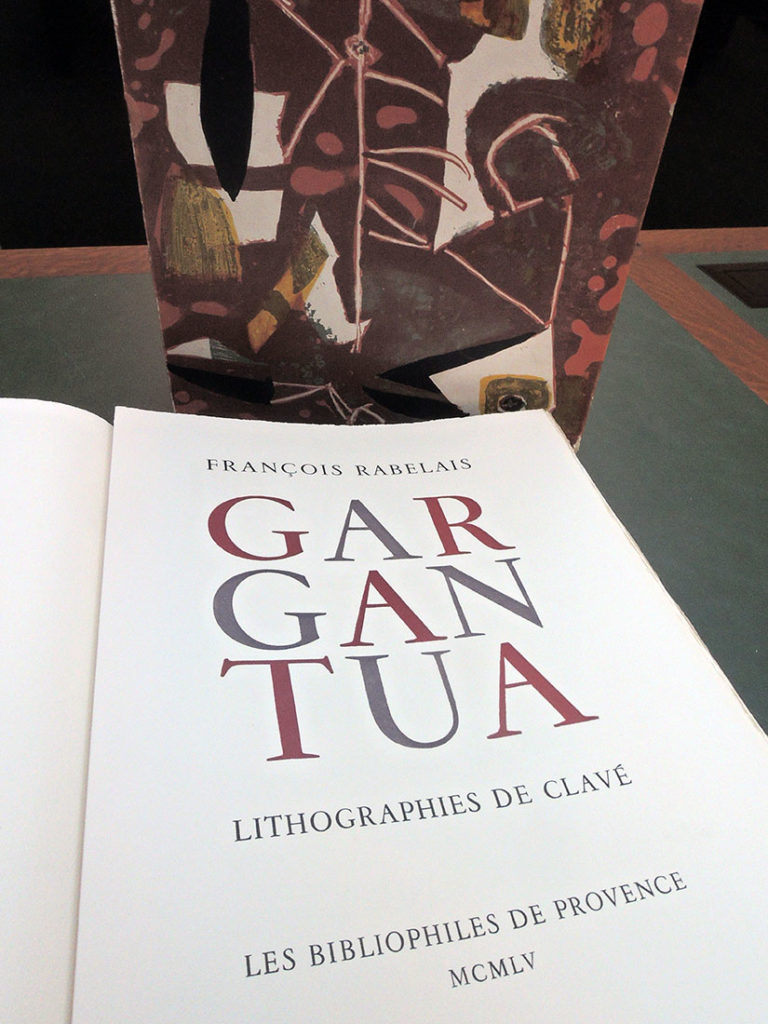

America is not alone. See also:

French: Tirage limité

German: Limitierte Ausgabe

Dutch: Beperkte oplage

Danish: Begrænset oplag

Italian: Tiratura limitata

Spanish: Tiraje limitado

Swedish: Begränsad upplaga

https://www.nypl.org/blog/2018/10/29/knowledgeispower-library-card