A great deal of research has been done on the book-length slave narratives published in the 1840s and 1850s. See in particular the chronology at http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/chronbio.html#1850.

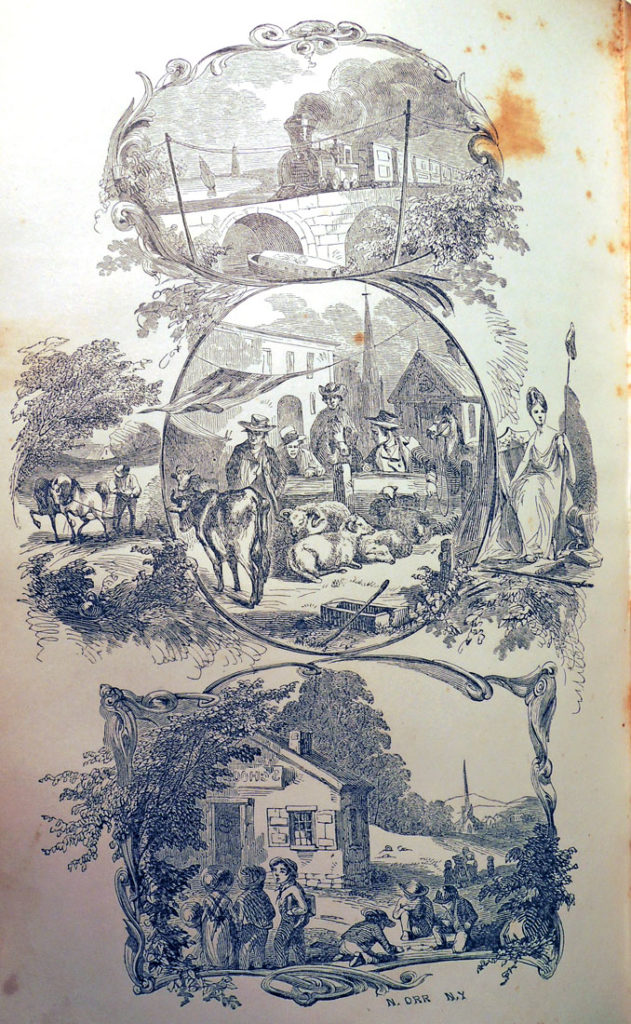

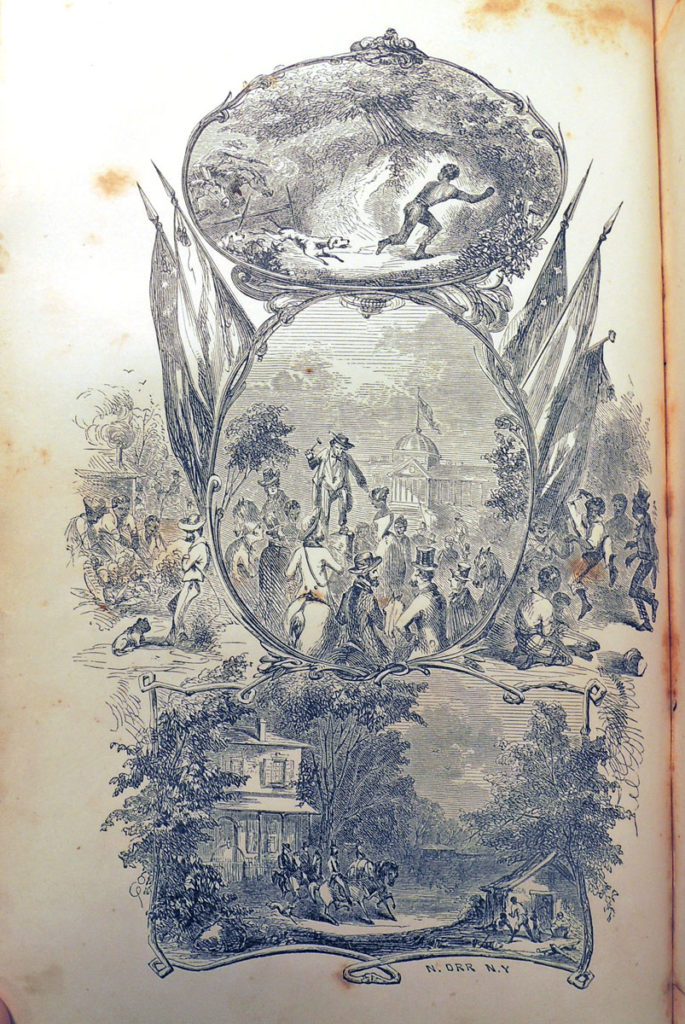

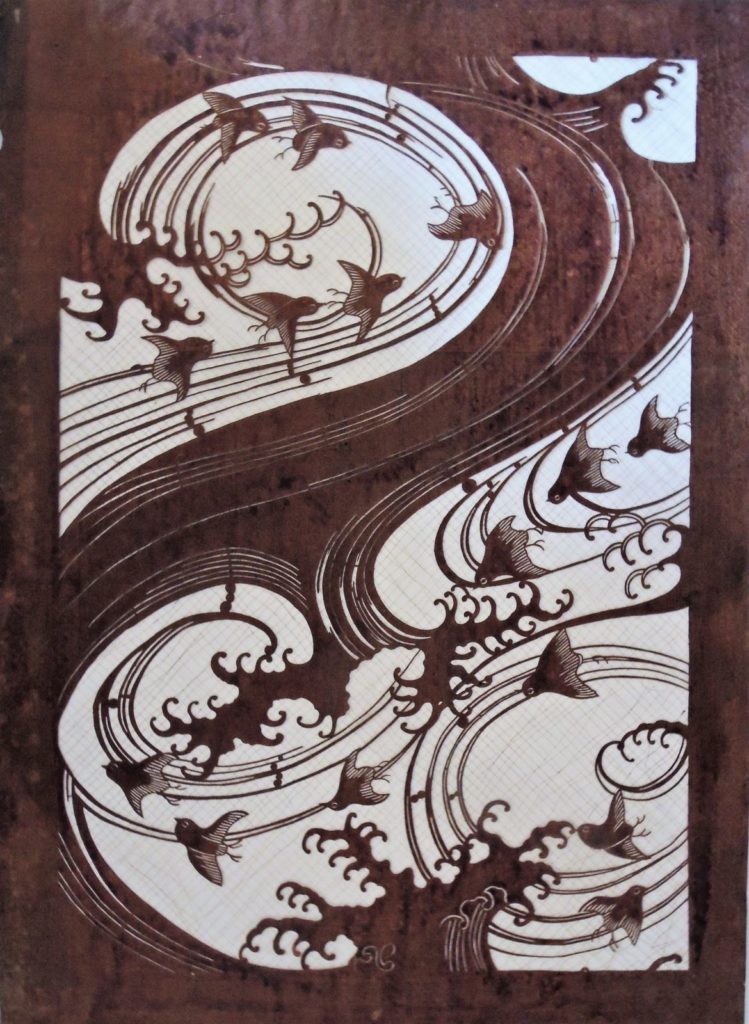

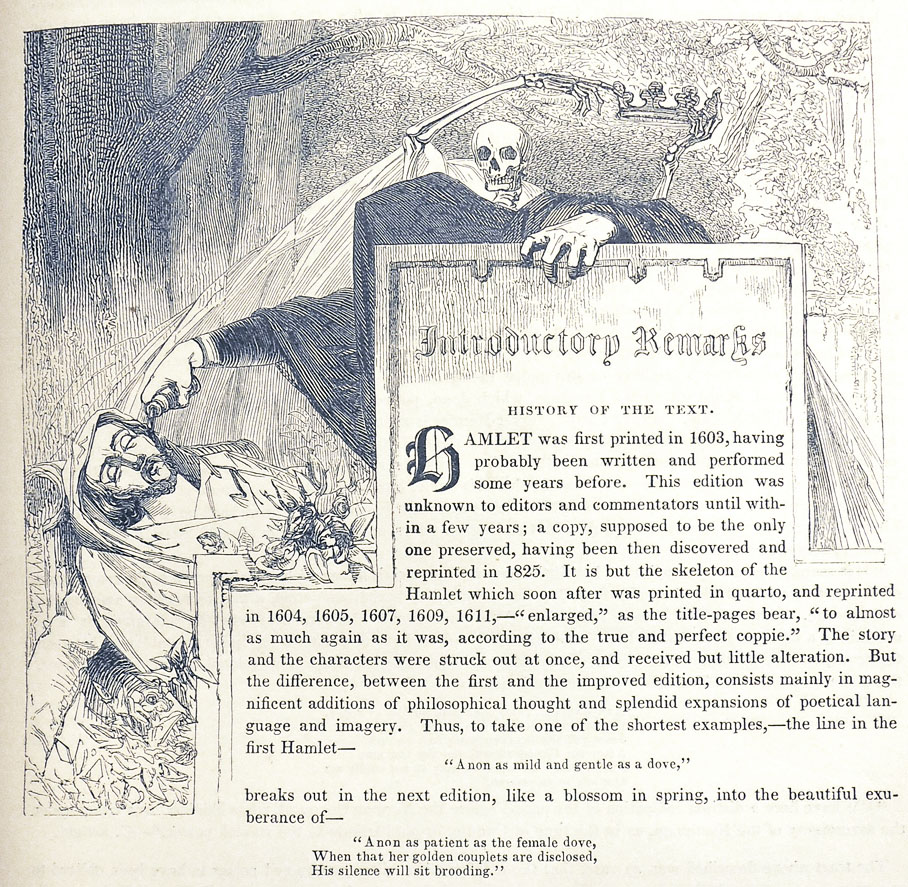

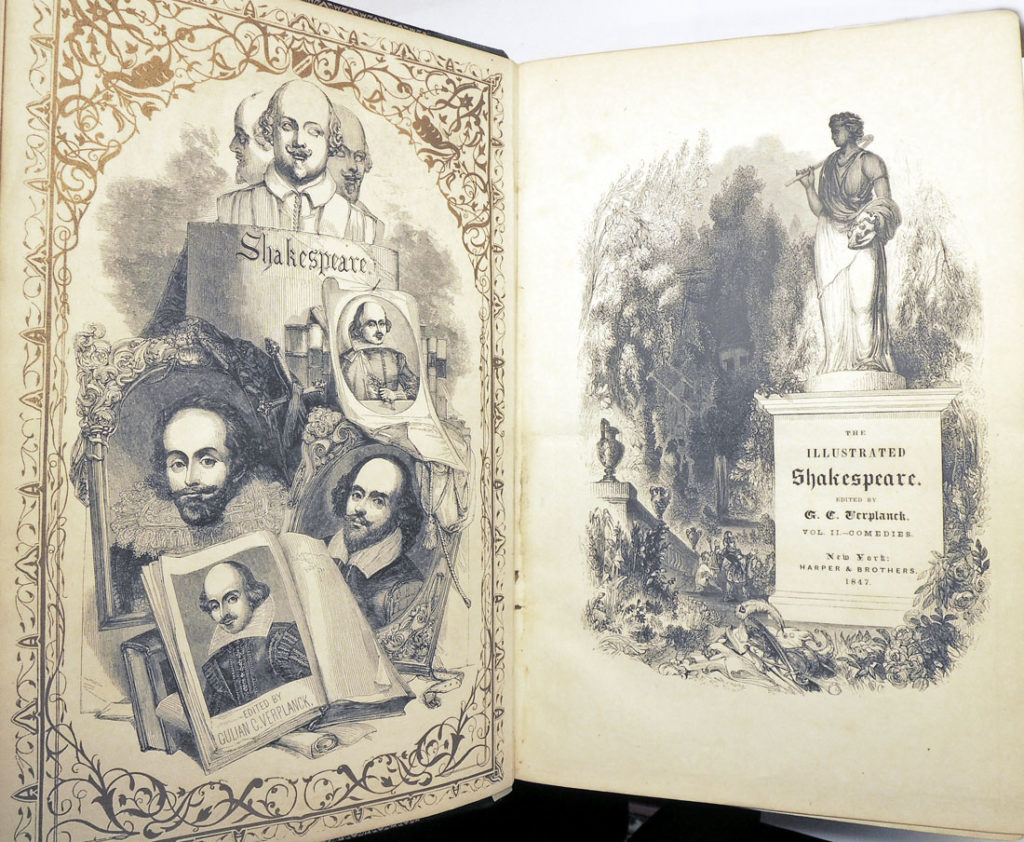

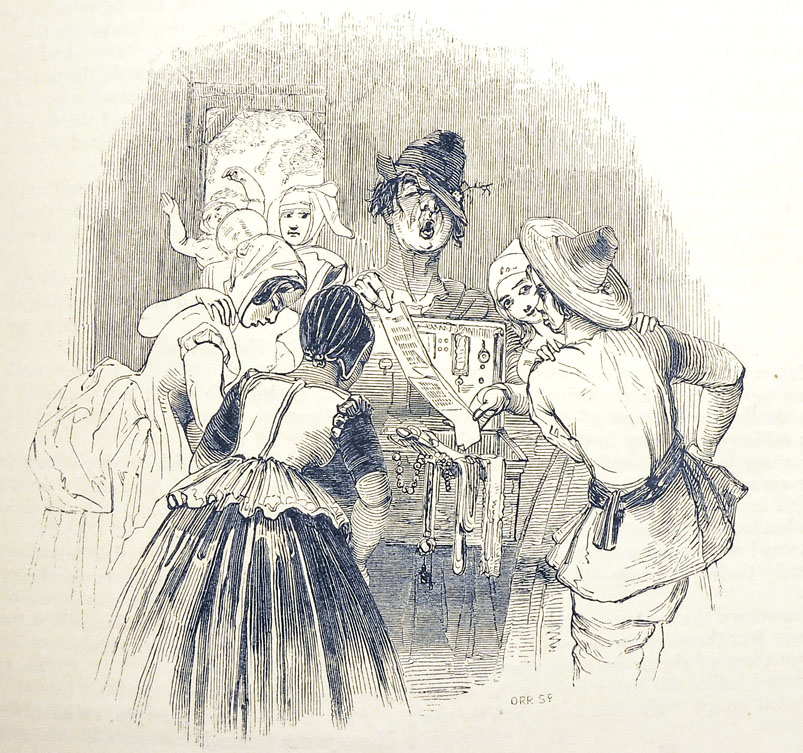

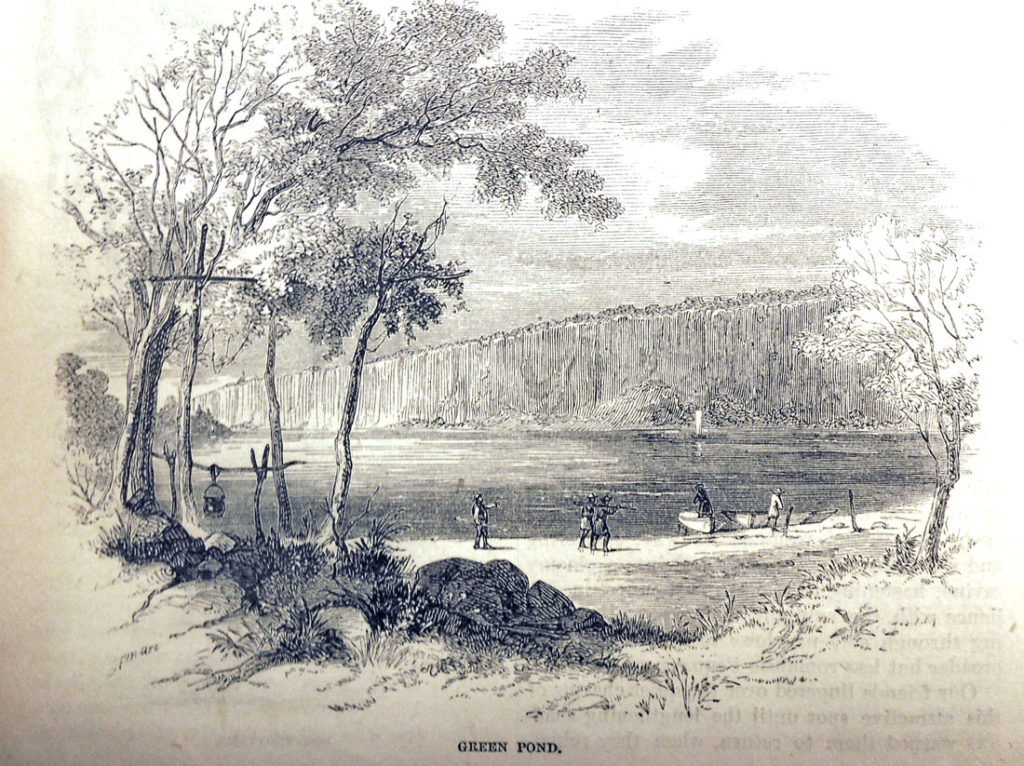

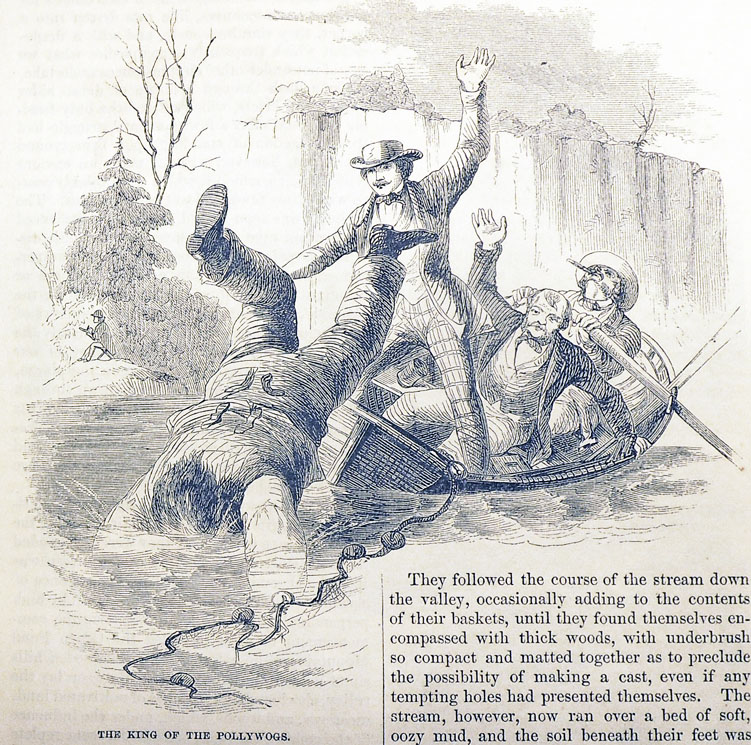

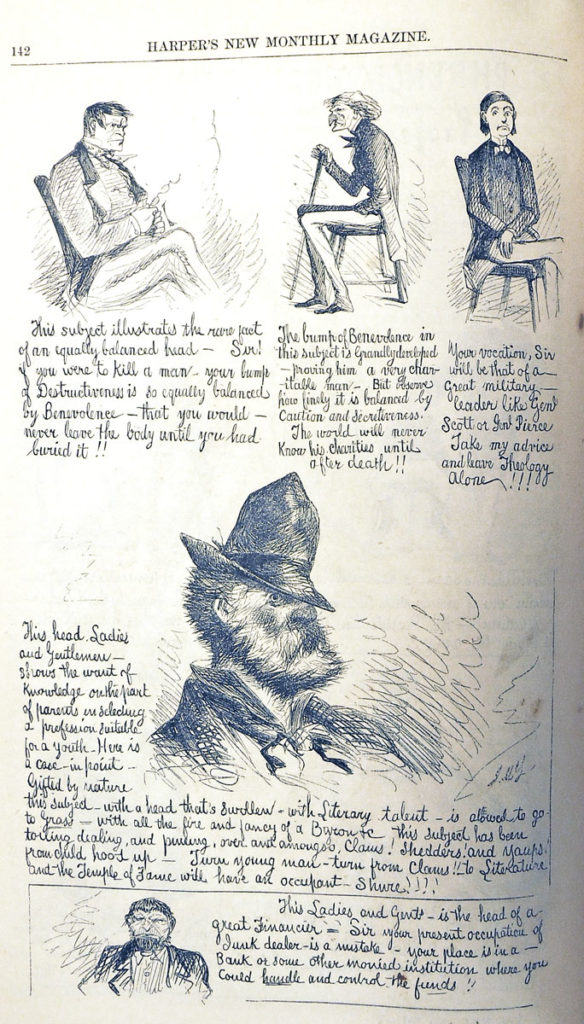

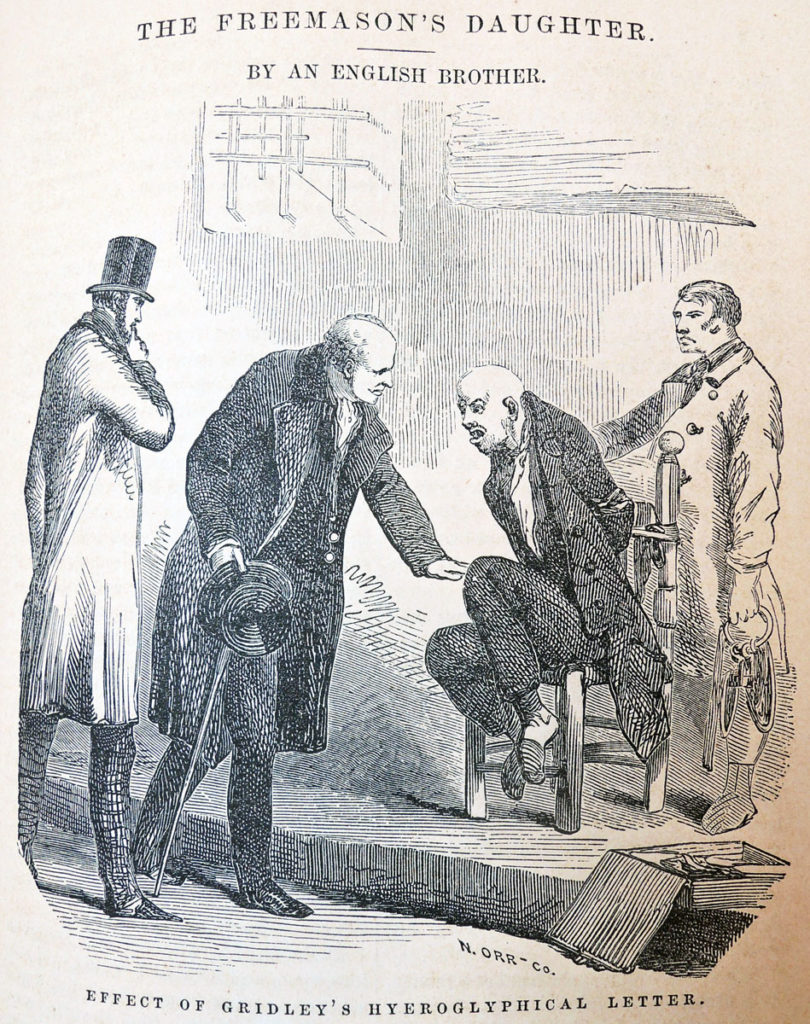

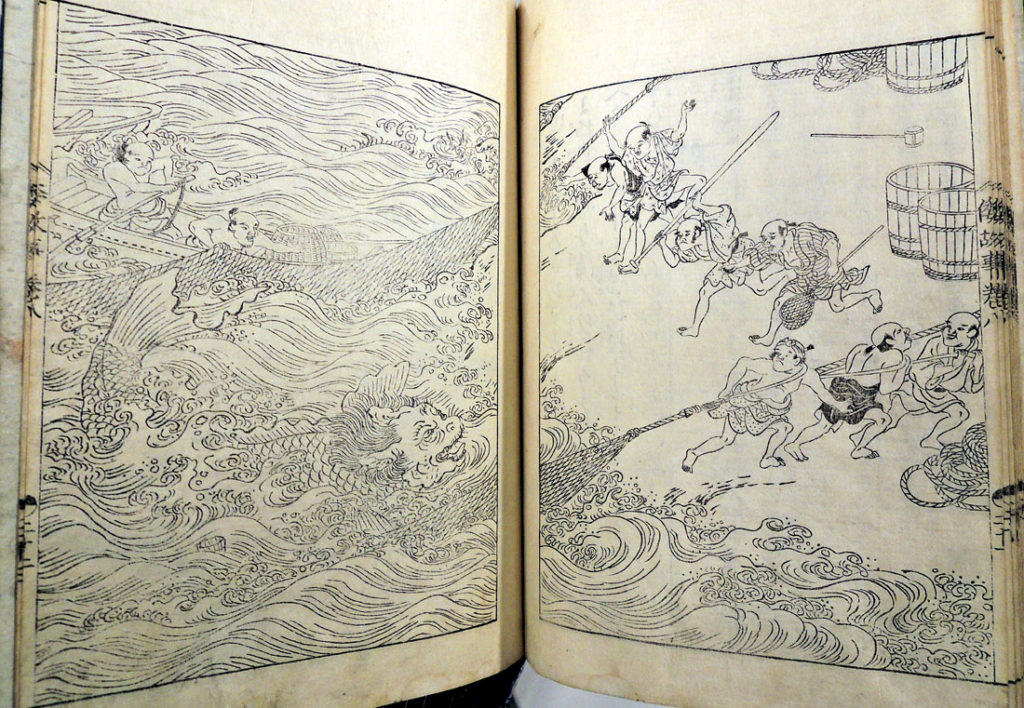

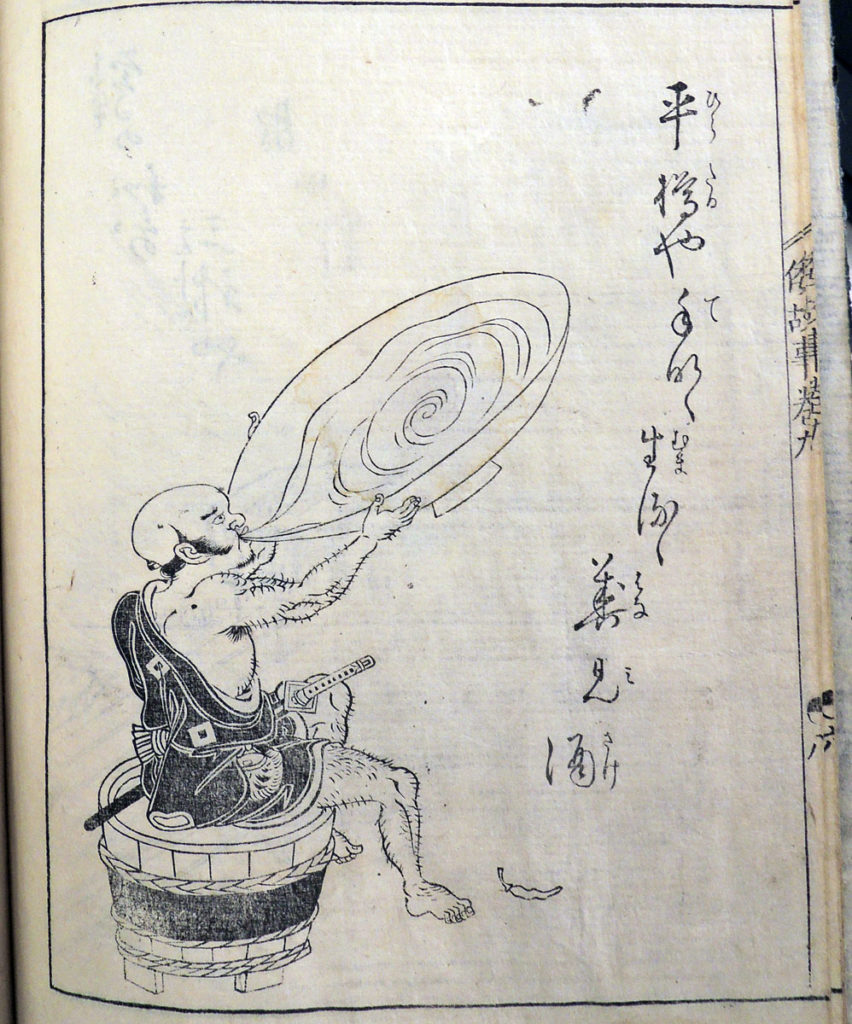

Yet few sources note that many, if not most, of the volumes are illustrated with plates engraved by Nathaniel Orr (1822-1908) and his firm at 52 John Street. Even after Orr moved to New York City in 1843, he maintained contact with the upstate New York publishing firm of Derby and Miller (later Miller, Orton, and Mulligan), “the largest miscellaneous book publishers of any in the State out of the city of New York.” Orr was their preferred wood engraver, only going to others when Orr was too busy to take on additional work.

Despite the success of these books, each selling thousands of copies, the bulk of Orr’s correspondence during these years are letters begging the publishers for payment. The work was always completed and returned to each firm along with an invoice, which often went months before the bank deposit was made. Pledges to do better were often effusive, such as Thurber W. Brown’s letter in 1851 responded to Orr’s request for money. “Your note came to hand this evening [concerning] bills . . . When you dread bankruptcy, send me by telegraph and if I owe you anything I will pledge my clothes for your benefit and come to New York on foot to bring the money.” (George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida).

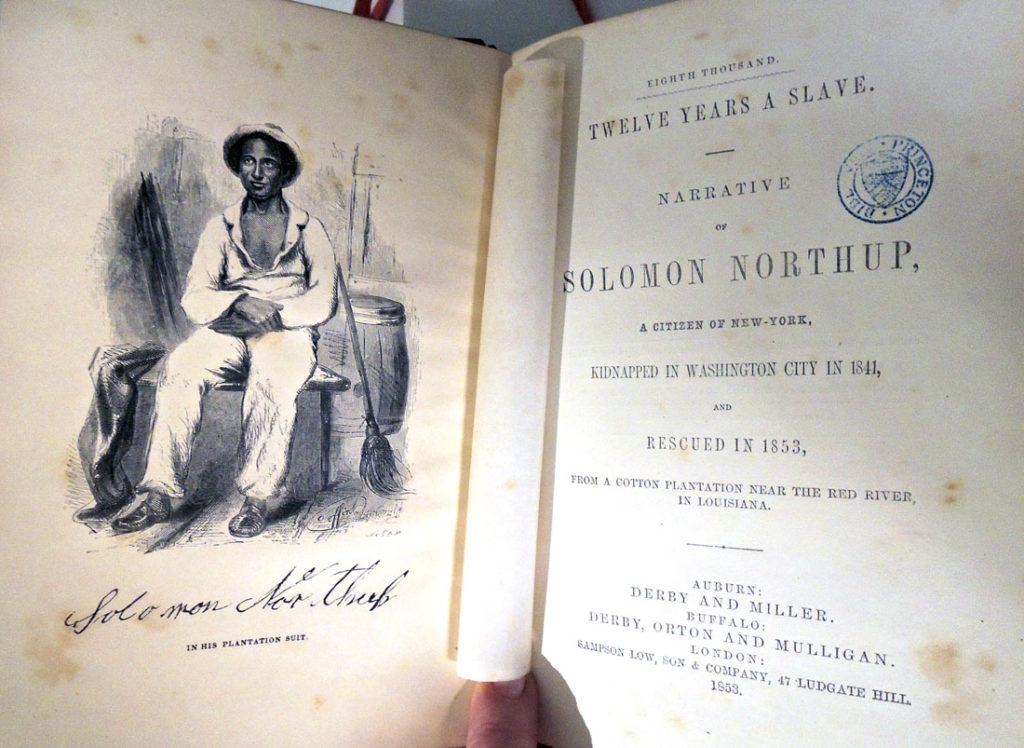

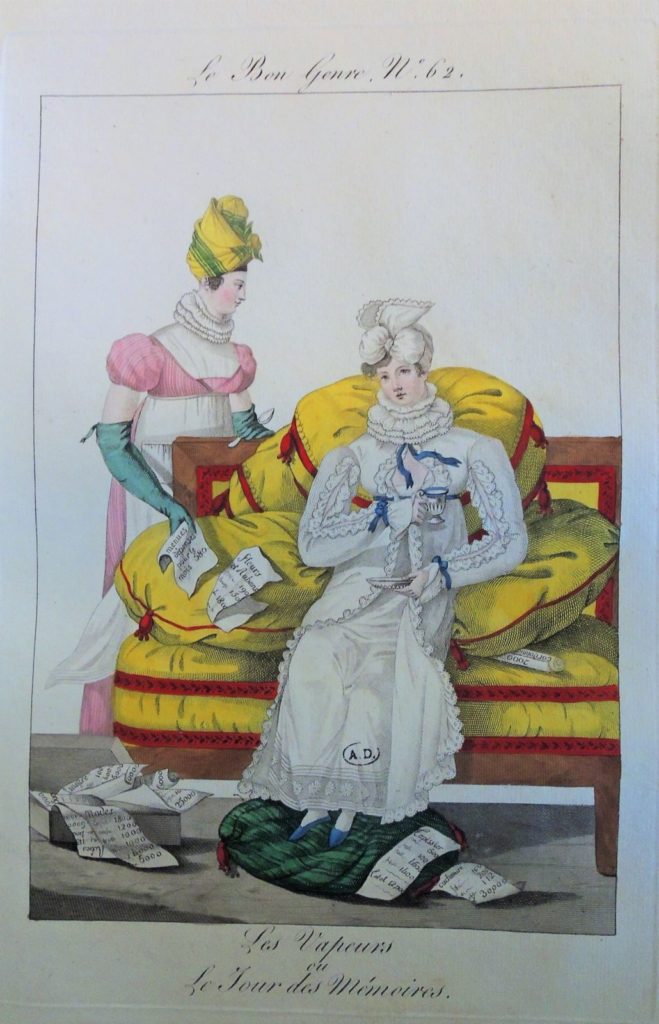

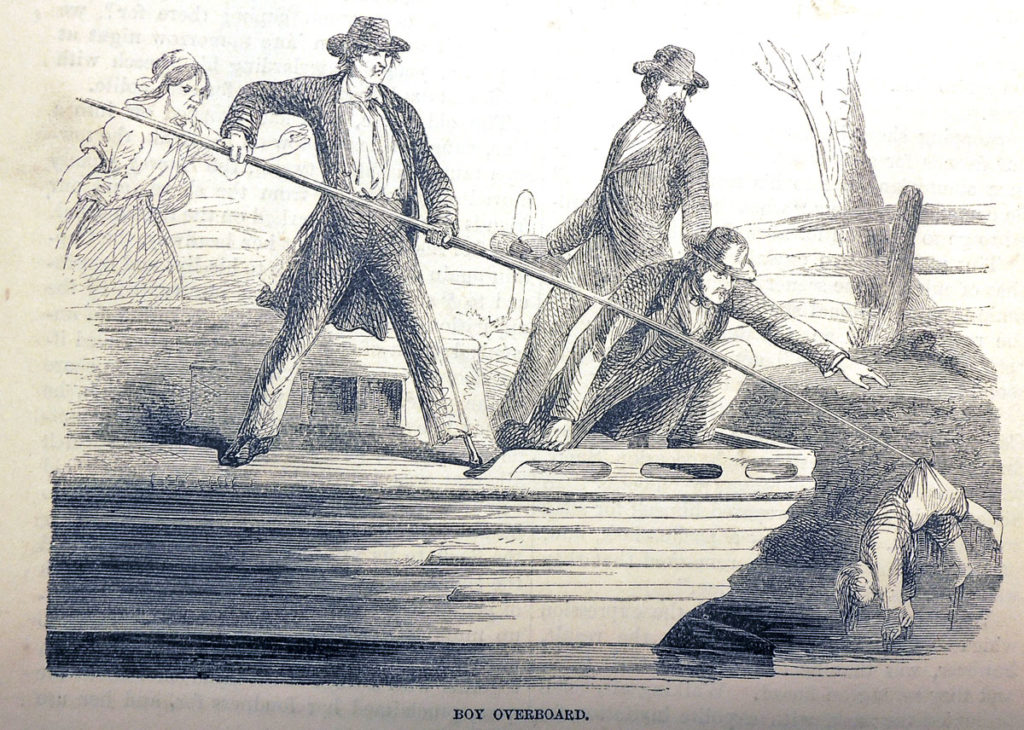

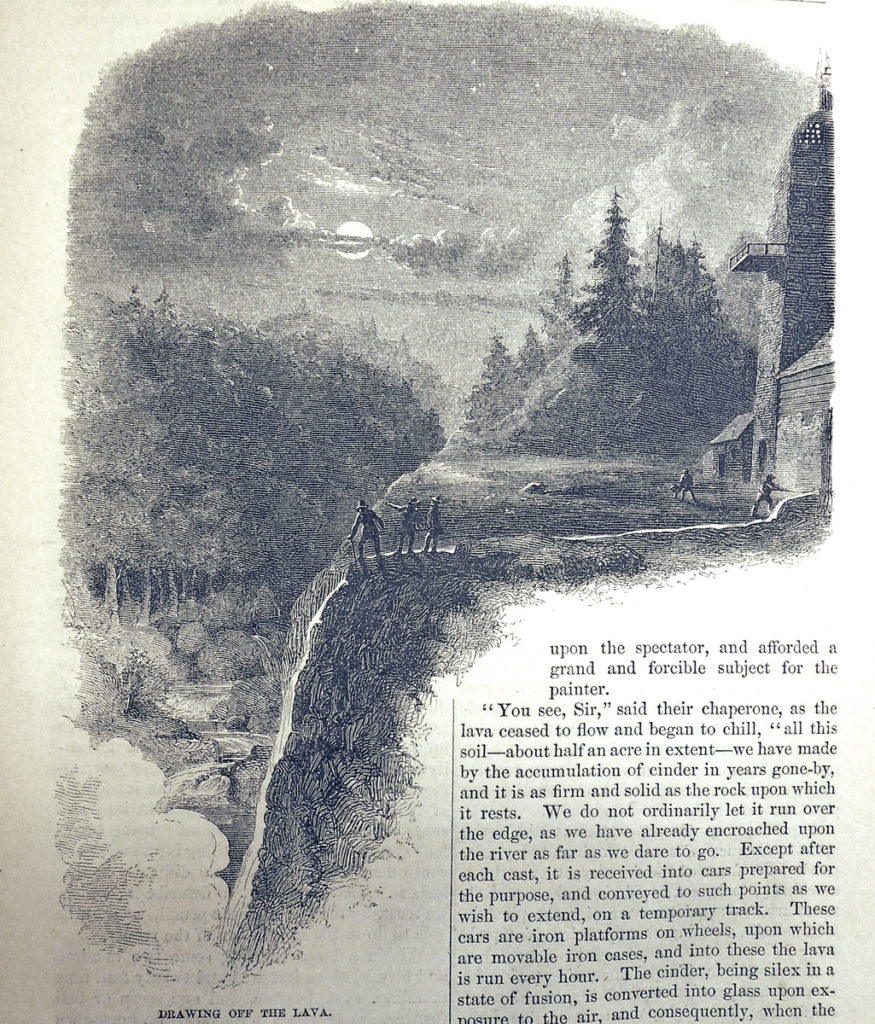

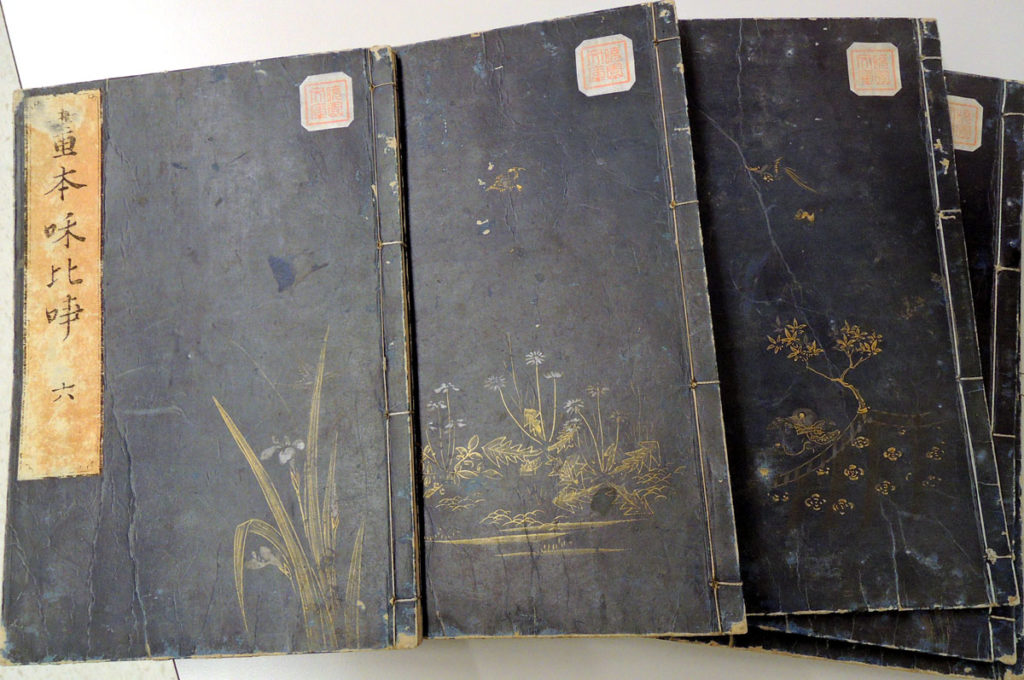

Solomon Northup (1808-1863?), Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup, a Citizen of New-York, Kidnapped in Washington City in 1841, and Rescued in 1853, from a Cotton Plantation Near the Red River in Louisiana (London: S. Low, Son & Co.; Auburn: Derby & Miller, 1853). Rare Books: John Shaw Pierson Civil War Collection (W) W91.687

Solomon Northup (1808-1863?), Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup, a Citizen of New-York, Kidnapped in Washington City in 1841, and Rescued in 1853, from a Cotton Plantation Near the Red River in Louisiana (London: S. Low, Son & Co.; Auburn: Derby & Miller, 1853). Rare Books: John Shaw Pierson Civil War Collection (W) W91.687

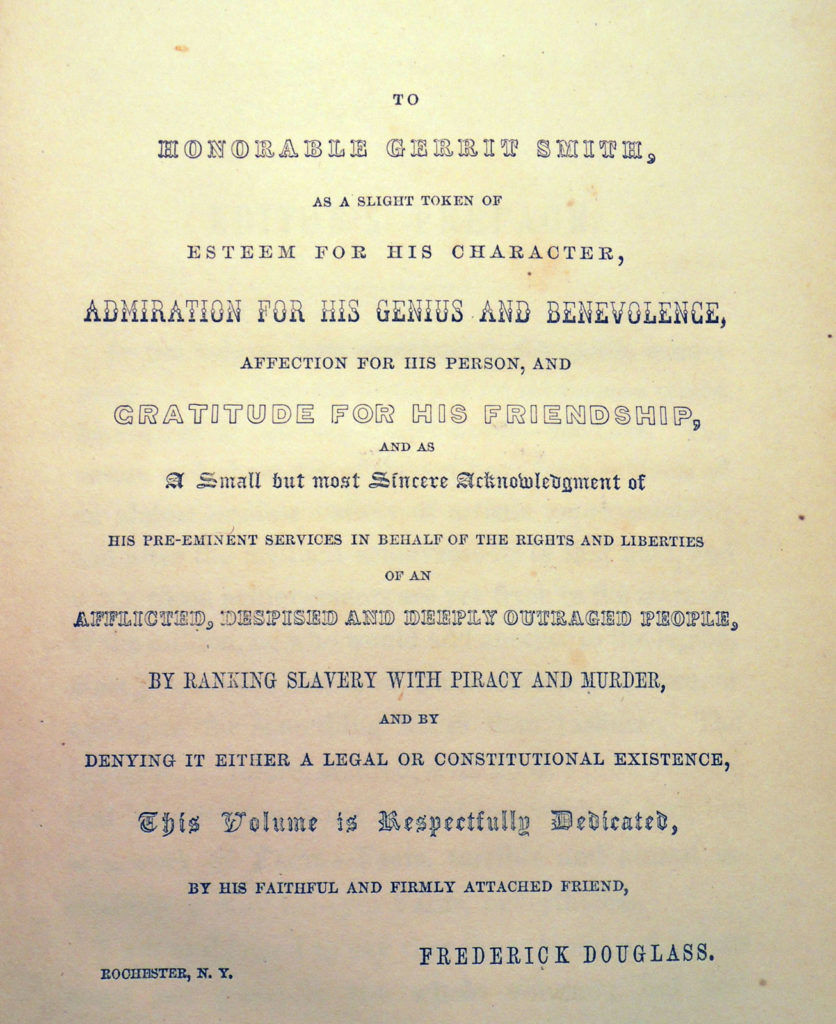

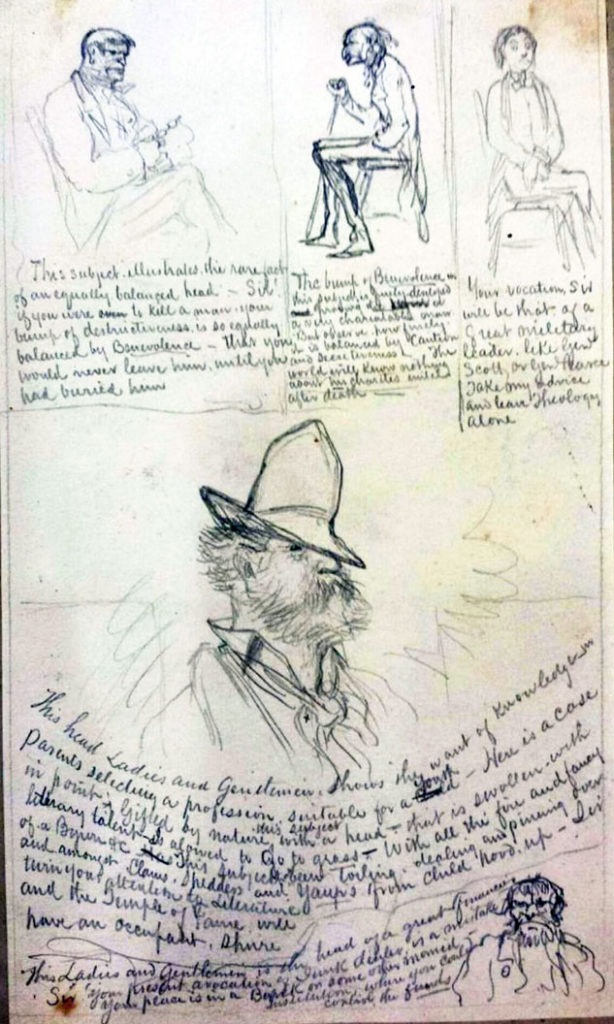

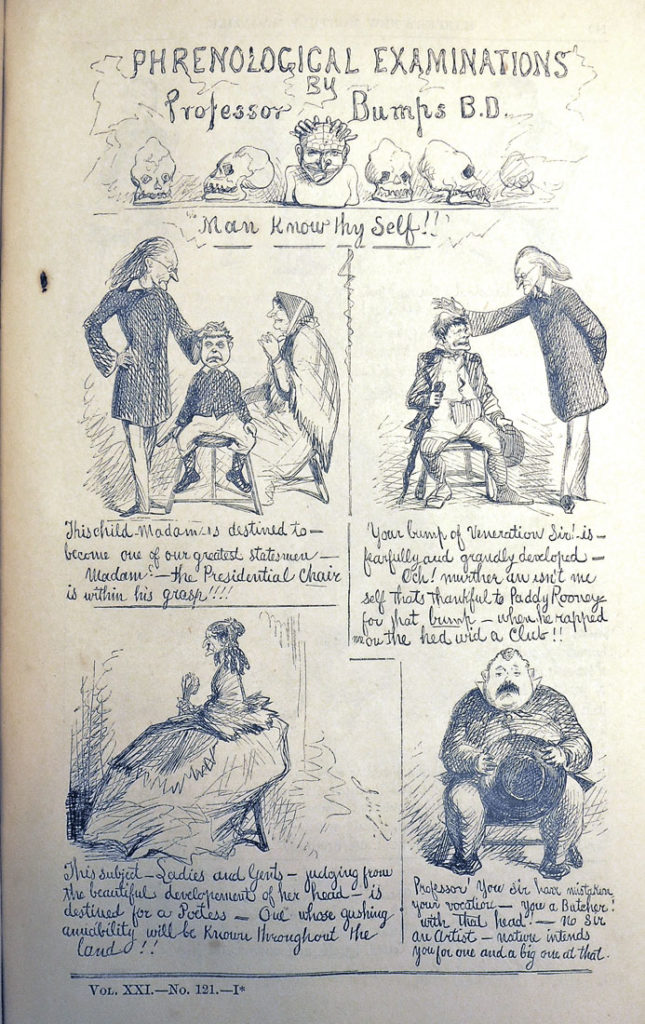

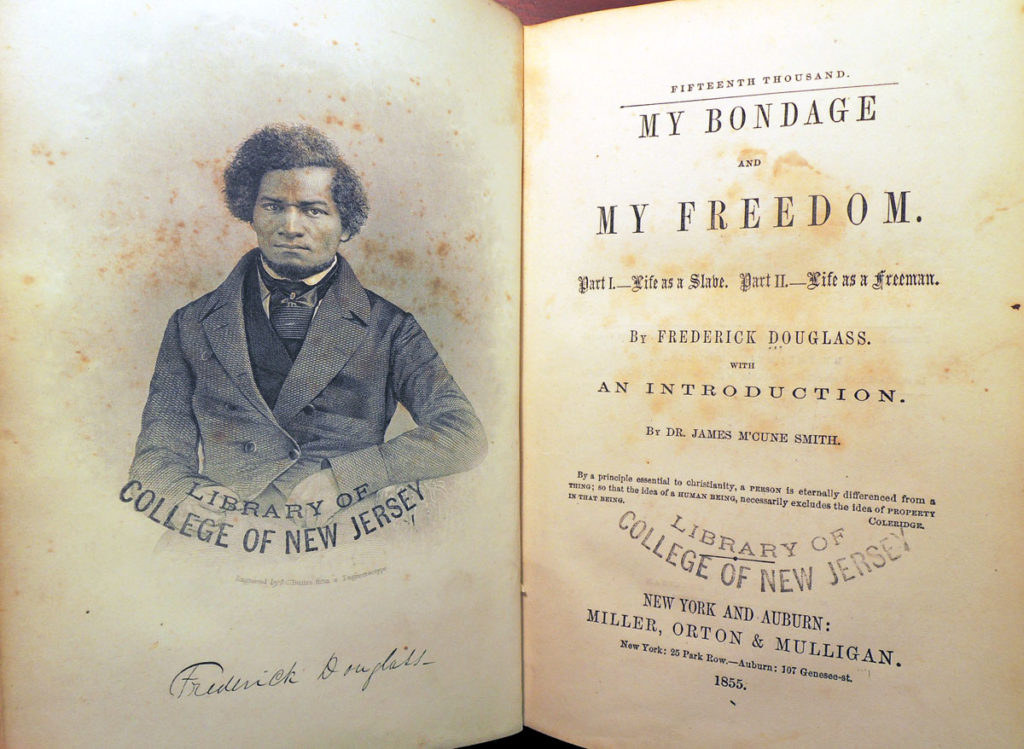

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895), My Bondage and My Freedom … With an introduction by Dr. James M’Cune Smith (New York: Miller, Orton & Mulligan, 1855). Rare Books: John Shaw Pierson Civil War Collection (W) W96.308.5

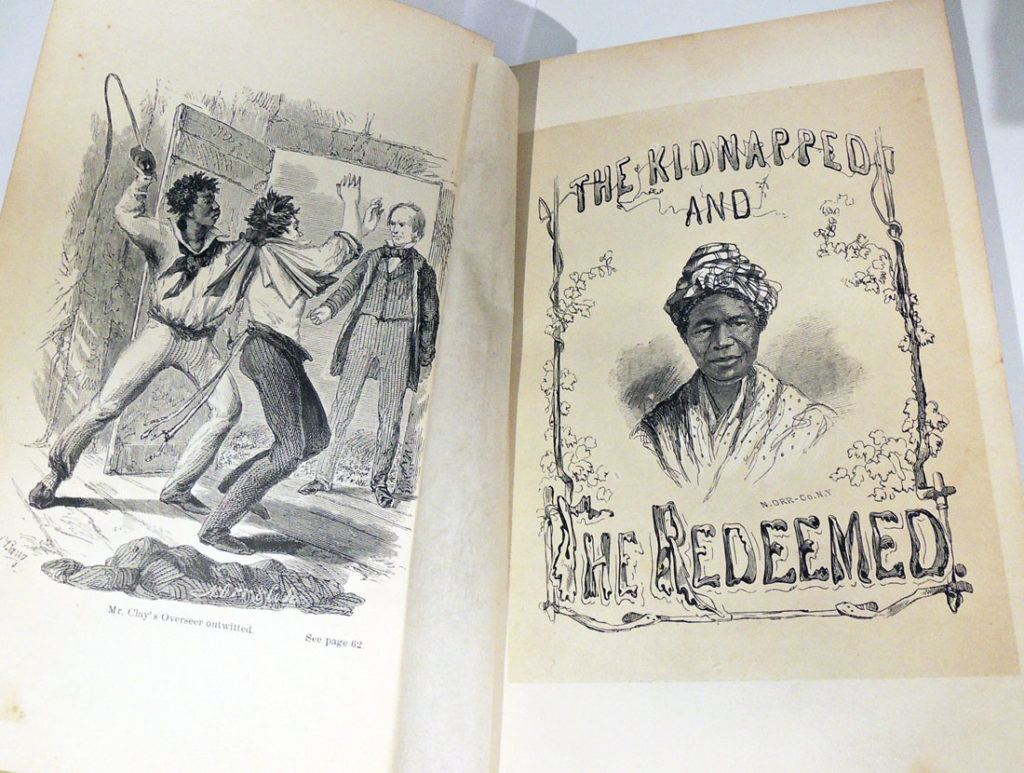

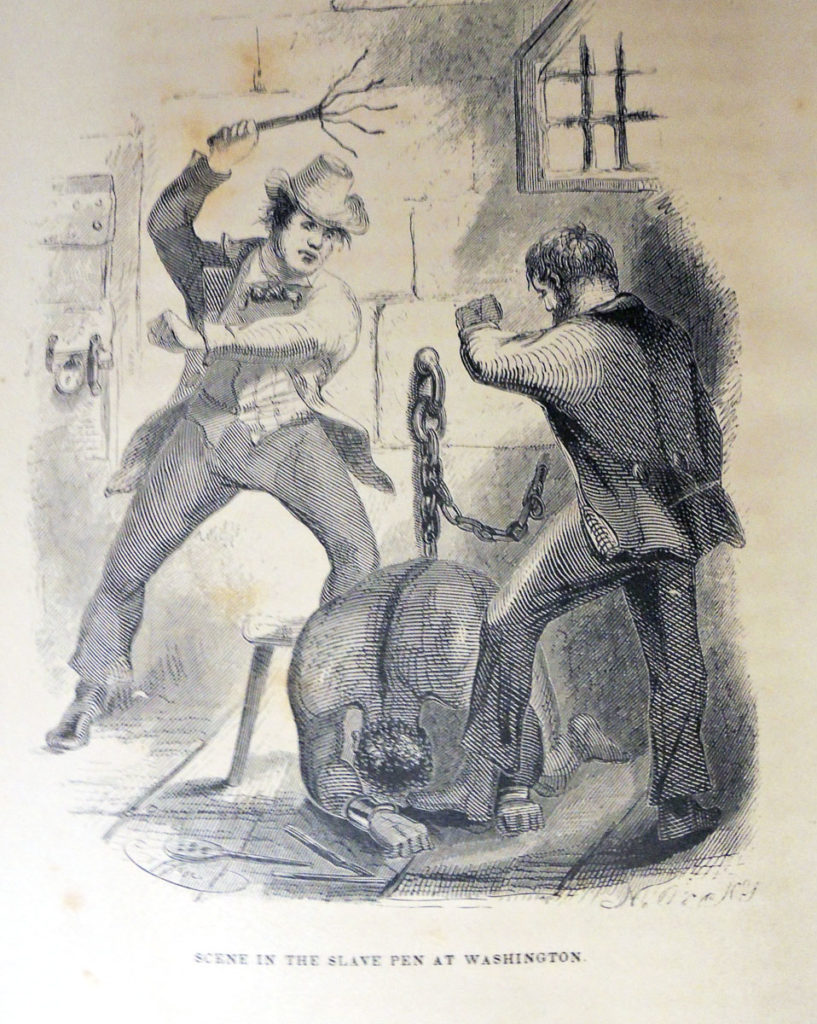

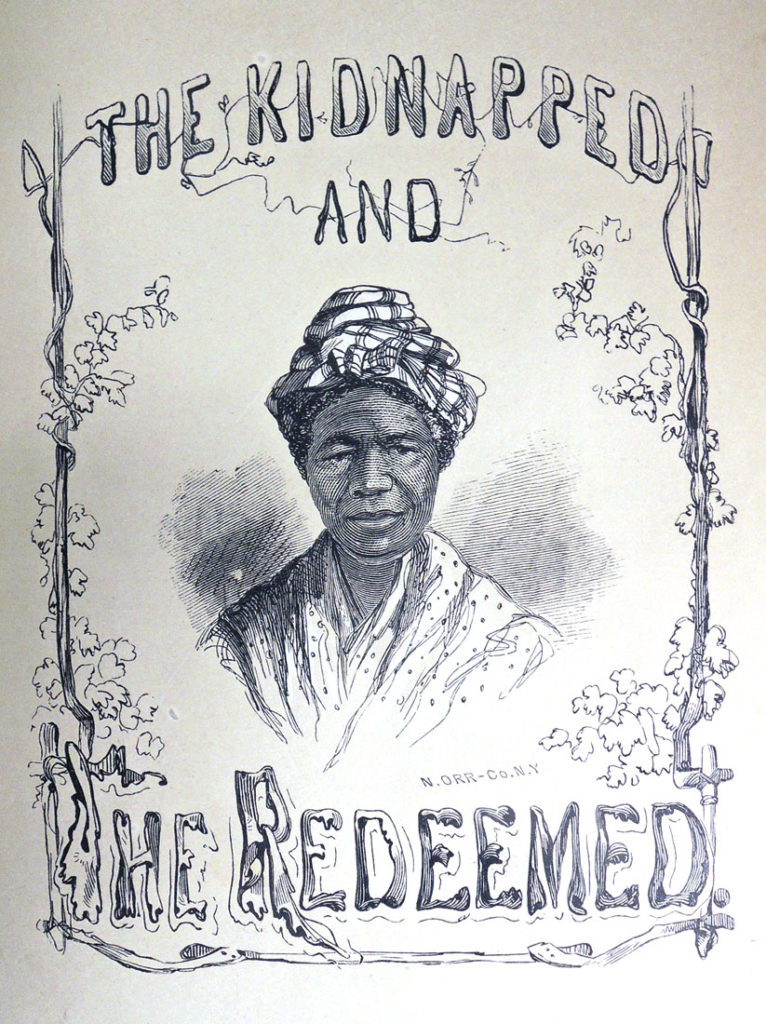

Kate E. R. Pickard, The Kidnapped and the Ransomed. Being the Personal Recollections of Peter Still and His Wife “Vina,” After Forty Years of Slavery, With an introd. by Rev. Samuel J. May; and an appendix by William H. Furness, D.D. (Syracuse: W. T. Hamilton; New York [etc.] Miller, Orton and Mulligan, 1856). With 3 full page illustrations by Charles A. Barry, engraved on wood by N. Orr-Co. Graphic Arts Collection (GAX) Hamilton 1489